All 74 entries tagged Bmw Gs

No other Warwick Blogs use the tag Bmw Gs on entries | View entries tagged Bmw Gs at Technorati | View all 24 images tagged Bmw Gs

November 20, 2007

One Man Caravan by Robert Edison Fulton Jr. – review

- Title:

- Rating:

To mankind’s age old comment on the journey of life that “the first hundred years are the hardest,” the traveler on a motorcycle could add that the first thousand miles are equally tough. p.12

And what of those first thousands miles, down the Dover road and across a depressed Europe, June 1932? Tedium and the uncomfortable wearing together of metal, rubber, muscle and bones that motorcycle manufacturers term “the running-in period”. Robert Edison Fulton Jnr. was perhaps the first of many to take the hard way round: eastwards across Europe, the Middle East, Asia and the USA. Ted Simon recommended this book to me. Bernd Tesch provides the foreward to this recent edition. They both know what it’s like to sit high over a rumbling air-cooled boxer engine for immense distances. Ted and Bernd ride BMW GSs, like mine. As travelers and writers, we are all descended from Bob Fulton, just as the DNA of his boxer engined Douglas bike is present even today in the latest high powered BMW bikes (some authorities claim that BMW copied the Douglas engine for its early bikes, mounting it transversally rather than longitudinally).

Every long journey by motorcycle has its “running-in period”, whether aboard a new machine or revisiting an old companion. But it doesn’t stop there. Beyond that first 1000, there is a slow oscillation around the point at which all runs smoothly. On a bike their is a much tighter and much more critical feedback loop between the environment, the mind and body of the rider, and the machine; all in fine balance, or working their way out of equilibrium:

As the day wore on the sound became more alarming. When I started that morning, the steady drone of the exhaust had been deep and chesty. But now, after half-a-dozen hours of desert driving, it seemed to fill with static, the machine began to wobble, the tires seemed flat, the whole engine seemed on the verge of falling apart, collapsing.

It wasn’t the machine, it was nerves; strung tight, pulled tighter by the constant thought of “what would happen if something happened?” p.65

Ride a motorcycle if you want to know and master paranoia; get a grip upon the awful power of the human mind to envisage even unlikely disasters, and to be pulled head first towards them. Psychologists now call this “target fixation”. If you look at the kerb you will hit it. That’s lesson 1 on day 1 of any riding course.

Bob Fulton’s journey is about transforming that negative target fixation into something positive: how to fall into the right kind of trouble; how to make something out of almost nothing, even amongst the emptiness and desolation of receding empires and expanding deserts. It is quite an amazing story. In many ways such a journey was easier then. America hadn’t given its people an often undeserved bad name. Imperial outposts provided staging points and frontiers linking every hiding place. Even beyond the beat of the colonial bobbies, their influence reached far: his ride into tribal Afghanistan would make a modern traveller deeply jealous. Then it was treacherous, coming at the tale-end of a serious disruption of the internal balance of terrors. Islamic hospitality was his saviour, along with enlightened rulers and friendly peasants. Now, especially for an American, it would be impossible. One is reminded of Chevy Chase hanging upside down from a wooden post: “hi, we’re Americans” – big mistake, one of many.

And after the Middle East and Central Asia, on to “French” Indo-China as it was then, before the first great US foreign policy disaster extinguished that world of relative innocence. He had assumed the service station owner at Angkor, Cambodia, was trying to rip him off. In fact it was the other way round: he was trying to give money to the brave motorcyclist! Bob Fulton realised, as many others have since, that the world is on the whole friendly and helpful, on a personal level. It’s on a more international global level that nightmares erupt. Japan for example, which in 1933 was deeply in love with all things American. If the Kobe Motorcycle Club had achieved the political power that they so clearly deserved, WWII might have been settled on the race track, aboard Indians and Harleys. And Bob Fulton might have been there cheering his new friends on. At a personal level, amongst the small band of Japanese riders with whom he crossed the islands, there could only ever be great respect.

One Man Caravan: a great adventure. Well written, with a scattering of fascinating pictures and maps. Honest. Full of excitement and exoticism, but with many connections between that world (now disappeared) and the present day.June 24, 2007

Riding the Ruta de la Plata, part 6

Follow-up to Riding the Ruta de la Plata, part 5 from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

Part 1: Santander landing, camping in the Picos de Europa

Part 2: Cares River, Desfiladero de los Boyes gorge, Peurto del Ponton pass

Part 3: Easter processions in León

Part 4: Plasencia

Part 5: Extremadura

Day 6 - into Seville

Snowbound peaks puncutate the horizon to the north of the town of Plasencia, itself with a modest elevation of 316 metres. The morning was bright and dry, with no sign of storm clouds wrapping the distant mountains in the grey menace of the previous day. We packed away our camping equipment, a process now becoming habitual (with my cavernous Tesch panniers, packing is easy). Heading south we initiated a day long descent towards Seville, rolling down on to the wide flat flood plains of the Rio Guadalquivir. Firstly, however, the tight turns and hills of Monfrague National Park's minor roads provided an early morning twist to the plot. As ever, Martin on the faster R1100GS found swift lines through the hairpins, imitating those swooping birds as closely as is possible on a 250kg motorcycle. I convinced myself that his espíritu del camino would simply result in passing the wonderful landscape and birdlife with a tunnel visioned ignorance. My assumption was that upon finally meeting further along the road, I should be able to disapoint my companion with tales of hoopoes, merlins, kites, eagles and storks. He had, of course, spotted all of those and more.

Beyond the park, we rejoined a bigger more certain road, progressively widening like a river approaching the ocean. It drew a line heading southwards, the straight path of which should have suggested its ancient historical origins. On past the town of Cacares, with atmosphere and character becoming progressively more Andalucian, I noticed a road sign that had first interested me on the mountainous road into Bejar:

"Ruta de la Plata"

That does sound heroic. Riding motorcycles along the route of silver. Through the homeland of Pizarro. Conquistadors. So rich were they in silver that they were compelled to seek an even more precious metal, far off in the land of Atahualpa. But to us now, more precious would be this thought: perhaps this road could give some narrative unity to what had so far been a rather haphazard expedition. At one point we travelled through an ancient industrial landscape, now covered with grass and low shrubs. Silver minings perhaps? One could imagine this to have been a route of power, culture and trade, borne along with the caravans of precious metal. No doubt an attraction to the empires that ebbed and flowed over this land: Visigoths, Romans, Moors, Catholics, Republicans and Fascists. We passed Moorish castles, tall and dark strongholds looking out from their cool and shaded interiors across an increasingly hot flat territory. Not only history here though, great wind farms and solar power stations place the landscape in a future just now being realised, a future that exploits the burning heat and light of this land, rather than seeking to hide from it in deep courtyards behind castellated walls. Will the axis of capitalism and civilisation once more drift southwards to Spain when Northern Europe runs out of gas?

An andalucian landscape

This road, the Ruta de la Plata, is in fact important enough to have its own web site, representing the trading and cultural alliance of the many towns through which it passes (from Gijón on the north coast via Leon, Bejar, Plasencia, Cáceres and Zafra to Seville). Spoiling the romance of the road somewhat, the web site seems to claim that the naming of the road has nothing to with precious metal. Rather, it refers to the way in which the original Roman road appeared to be made of metal, a consequence of the applied techniques of construction (as we say in English, it was a 'metalled' road). Whatever the origins of its title, I was happy with the idea that we had been vaguely following the Ruta da la Plata from the Bay of Biscay, and would continue to do so all of the way to Seville.

Passing through towns and villages with greater frequency, finally a hunger for fuel stopped us. My GS Paris Dakar makes 300 miles before reserve, so stops are more rare than one would expect. The service station provided gasoline and more of the freshly made coffee that powers Spain. As we sat resting, several other small groups of bikes passed by, mostly sports bikes, enjoying a great road. A group of new BMW bikes stopped for fuel, led by a K1200S badged to identify it as a demonstrater from a BMW dealership in Seville. We had started seeing new beemers in Plasencia. I knew that we would see more of them as we got closer to the capital of Andalucia - they are somehow more appropriate here. As for the big K1200S, a fully faired sports touring rocket, perhaps the fastest vehicle on the roads (0 to 60 mph in 2.8 seconds), what a great bike to be riding on fast sweeping roads like these!

We made one further stop before Seville, finding a bench in a small town from which to plan our attack on the big city. Our conference was gently interrupted by the most subtle act of begging that I have ever encountered, so subtle in approach that I failed to recognize it as such. He was somehow anachronistic in his appearance, perhaps even belonging to no particular place or time. Thin, but not painfuly so, with dark hair and olive skin. He wore a green corduroy jacket, stiff brown brogues, with no socks. That final detail was diagnostic. We had no common language. He was obviously not Spanish. Martin cycled through some possibilities, experimentally offering phrases in French, German, Russian, with Chinese added as a joke. "Roma" he said in reply. Obvious. But perhaps political correctness had drawn us away from the truth. "Narok!" I exclaimed, while miming the act of drinking a glass of beer. I don't know much about Romanian, but I know what I like. With a minimal common understanding established, he had just enough time to tell us of his own expedition traveling around Europe by bus in search of work. And then suddenly he was gone, back on to the bus heading North.

The view along the Rio Guadalquivir

Our plan for Seville was simple. The Ruta would first widen out into three lanes, with a spur shooting off along the industrialized western suburbs towards Donana. We would turn eastwards from this and ride straight into the centre. I know Seville. It is an easy place to navigate, with many landmarks and a simple layout. We rode first across the more natural of the Rio Guadalquivir's two channels. And then over the second, artificial channel. As always, the traffic was gentle and bike friendly. Across the other side, I led us along Paseo de Cristobal Colon, following the river, past the Plaza del Toros de la Maestranza (the bullring of Carmen), the Torre del Oro (golden tower) and the cathedral towards Parc María Luisa, rolling slowly by horse drawn taxi cabs with throttles calmed (although the horses must be used to noisy bikes). Then finally we turned away from the river along the edge of the Alcázares, parking up on the pavement at a nice restaurant next to the old hospital. In the restaurant, at last, we found good Spanish food, and the usual babble of smartly dressed families (each with representatives from several generations). And from there we could plan out our stay in Seville.

Horse drawn taxis in Seville

Toros de la Maestranza

Coming soon, "a day in Seville".

June 10, 2007

Riding the Ruta de la Plata, part 5

Follow-up to Riding the Ruta de la Plata, part 4 from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

Part 1: Santander landing, camping in the Picos de Europa

Part 2: Cares River, Desfiladero de los Boyes gorge, Peurto del Ponton pass

Part 3: Easter processions in León

Part 4: Plasencia

Extremadura

Shortly before entering the town of Plasencia the passing landscape had transformed quite suddenly into an unfamiliar pattern. The mountains gave way to more gentle slopes and plains, with views extended far across fields semi-cultivated with short and light trees. From the camp site at Plasencia mountains were still visible, but the greater heat signified lower altitudes and the approaching south. On our second evening a dramatic storm passed over, after winding its way for some time along the valley. We watched it approach, gambling upon the direction in which it would descend. And then the rain was heavy but brief, and failed to interrupt the warmth, which soon dried the ground and our tents.

It is this warm but damp climate that enables and sustains a unique environment. Extremadura is a little known corner of Spain, south-central and running up against the border of Portugal. Amongst two minority interest groups, however, it is famed and respected. Those great wide fields of trees once supplied much of the world's cork oak. To viticulturalists the bark of its definitive species of tree was essential. The landscape was until recent times shaped and dominated by that powerful industry. Disease and a move towards plastic "corks" has now weakened the link between landscape and industry in Extremadura. And that is bad news to the second interest group for whom this land is of importance. For wine consumers there may be justification in the use of modern materials as a means of sealing bottles. Plastic corks don't go bad. But they also don't sustain a rich diversity of wildlife. So the demise of the natural cork is regretted by the many naturalists who visit places like Parque Nacional de Monfrague.

Parque Nacional de Monfrague

Before settling upon the camp site in Plasencia, we had ridden all of the way through the park in search of accomodation. It was a bank holiday, and therefore quite busy. Half way through there is a a dramatic view from the road across to a rocky outcrop. Many people were at this viewpoint, pointing cameras, binoculars and telescopes into the air. We stopped and joined the spectacle. It was a sight that I have seen many times before, but only ever in Africa, and almost always in remote locations deep in the bush. Above us, spriralling out from the rocks, vultures swooped and glided. We spotted clearly two varieties, white backed and egyptian. The park also holds a population of black vultures, which may also have been in the crowded skies above.

Griffon or white backed vulture in Monfrague.

Our tally of vulture species was now at two. Add to that the numerous golden eagles, black kites, red kites, buzzards and falcons, and this had become an excellent expedition for raptor enthusiasts.

May 24, 2007

Riding the Ruta de la Plata, part 4

Follow-up to Riding the Ruta de la Plata, part 3 from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

Part 1: Santander landing, camping in the Picos de Europa

Part 2: Cares River, Desfiladero de los Boyes gorge, Peurto del Ponton pass

Part 3: Easter processions in León

Lost in La Mancha (or somewhere in Spain)

It had been a difficult day. But at least el Che, fellow motorcycle traveller, was there to meet us in the small Extremadura town of Plasencia. Our escape from León, haunted by the previous evening's experience, had been of the worst genre of nightmare: trapped in an infinite loop. We now knew what the mass processionists had really been up to as they marched around the town: they had hidden all of the signposts in order to punish the two heathen BMW riders. Within the centre of the city, not a single sign remained to indicate the correct direction out towards Extremadura. After several futile loops, we just got onto whichever main road seemed to head in appoximately the right direction. It was off course the wrong direction. And so we were magnetically drawn to Valladolid, to the East. Even a last minute attempt to find a cross country route was foiled by the European Union road building programme. A new road, not marked on my 2007 Michelin maps, led to confusion and eventually surrender.

Having passed through Valladolid with relatively little pain, we finally turned South to Salamanca. At the entrance to the city of Salamanca, our saviour arrived (praise the lord), aboard a 250cc Yamaha trail bike, revving competitively at the lights. Somehow I managed to mime our key message: please show us how to find the road to Bejar. He seemed to understand. Even more impressive, he led us patiently through the heavy traffic, realising that fat BMWs cannot squeeze through the same gaps as his traillee. We found the road out. He waived us on. We escaped, impressed with the generosity of the Spanish.

South from Salamanca, geographical interest returned. With mountains to each side of the road, and views across yet more reservoirs and up to snow covered peaks, our pace slowed. Having suffered, we agreed to look for somewhere to stop. Extramadura, our target, was still too far off. And therefore we paused for the night at a far-too-expensive hotel in the almost non-descript town of Bejar. The road in offered the most amazing sight: a mountainous rubbish dump colonised by a big flock of white storks (large birds). In fact the hotel was excellent, and cheap for one of its standard (about £40 for each of the two double rooms). With our bikes parked in an underground lair, we looked for food. Again the only option was pizza! Three days in Spain and little sign of classic Spanish food.

A short ride the following day led us into Extramadura and welcome changes. Is it possible to mark the transition from Northern Europe to the South? Perhaps the mural on this wall marks the spot? Or perhaps our first sighting of oranges growing in the streets.

Plasencia was, immediately, a hit. It has a different spirit. There is tradition, but also youthfulness, and some pleasing irreverance. The graffiti is as good as that of Barcelona.

Mr Capitalist gets his ass kicked

We stayed for a day and a half, with much of that time spent sipping strong coffee at the oddly named Cafe Parking (it is near to a well hidden car park, but the name does it injustice). From there we could see storks nesting, as they do all over town, as well as peregrines and kites high above.

Storks nesting in the cathedral

Short rambles were taken through the town centre, with tradition and the new both nearby.

The arch seems to bridge between two buildings to which it has no historical connection

Yes, that really is a surf shop in the middle of Spain

The camp site at Plasencia, a short ride outside of town, provided a popular base. But even there we found ourselves in a dramatically different culture, that of macho Spanish hunting and the matador. The number of stuffed animal heads pinned to the walls of bar was to both of us quite shocking. In Africa it's usual to see the odd impala head or zebra skin. But this was simply the result of a massacre - a global massacre. Animals from every conintent were present, crammed onto the walls, tongues hanging out as if strangulated. But of course they had a very different kind of death, as the TV show constantly playing on the big screen demonstrated. In a series of locations, swarms of heavily armed Spanish men leapt from 4x4s, released packs of salivating dogs, and blasted the wildlife to bits. In Britain hunting is rare, and usually undertaken for good reasons by highly skilled experts. In Spain, it seems, any one is welcome to blast off hundreds of rounds randomly. The TV show even included trophy hunters killing roan antelope in Africa. Roan! Beautiful endangered roan!

Bloodshed in the bar was followed by yet another unsatisfying plate of badly cooked meat and chips in the restraunt. This time we were surrounded by the heads of bulls, ritually slaughtered in the ring. And how odd, in the middle of the big collection of bullfighting memorabilia, a cabinet displaying a collection of military medals from around the world: a Purple Heart, the Order of Lenin, an Iron Cross, and the Victoria Cross. Death and glory!

Light relief was supplied by a visit to the local supermarket, a branch of Carrefour bigger than any shop that i've ever seen, and perhaps bigger than any building that I have ever been in. So vast is its floor space, that it is patrolled by a team of shop assistants on roller skates. Having failed to understand local shopping customs, one such girl snatched up my small bag of apples and piroueted off to the counter to have them weighed. Meanwhile the lovely checkout girl practised her quite good english. I like Plasencia.

May 11, 2007

Riding the Ruta de la Plata, part 3

Follow-up to Riding the Ruta de la Plata, part 2 from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

Part 1: Santander landing, camping in the Picos de Europa

Part 2: Cares River, Desfiladero de los Boyes gorge, Peurto del Ponton pass

Our second day in Spain had been a journey through unsubtle patterns of texture and rhythm. Our passage through the gorge was a rapid sequence of hairpins, barreling along steep rocky mountain walls. Like giant pinball, we bounced from one side to the next and back, occasionaly catching up with our own echoes. Light and shadow, dry warmth and cool dampness, exchanged places in quick sucession. And then the ascent, in which two opposite but more linear vectors passed each other: on the one hand, light and perspective grew as we rose out of the mountain shadows and into the peaks; whilst conversely but in proportion the temperature dropped to an altitudinal chill. Once past the route's highest point (1,280 metres), the road widened and adopted a lazier wind down onto the plateau towards León (883 metres).

In the mountains there had been griffon vultures waiting ready to capitalise on erroneous motorcylists. On the road out of the Picos, all the way into León, a series of funeral cars performed that role. After passing the fourth hearse in an hour, I started to think darker thoughts: remote rural communities, land and blood won through centuries of struggle. Were we perhaps in the middle of some kind of murderous feud? The coincidence seemed uncanny.

That evening, events out on the streets of León further amplified this sense of menace and the supernatural. Another unsubtle pattern of texture and rhythm. It emanated from the great gates of the gothic cathedral. We had established base camp within a room of the Pension Berta (15 Euros for a twin room), looking out onto the Plaza Mayor in the epicentre of town.

View from the Pension Berta, with the following morning's market being assesmbled.

Down below in the street, hundreds of heavily disguised bodies bobbed from side to side synchronously, edging forwards like a slow moving river passing heavily through the gorge formed closely by the surrounding buildings. Loosely coordinated by some heavily veiled intention, they solemnly proceeded. An accompainiment of marshall drum beats and raucous un-earthly trumpets seemed to have no effect other than to reinforce a deeply buried fatalism. Time, life, death, sin, purgatory, penitence and glory would just carry on as determined by the natural and supernatural order of things.

A heavenly cacophony.

Until then I had not realised just what it means to have grown up in a Protestant culture. This Semana Santa (Easter) procession in Catholic León was almost impossible for me to decipher. The audience of onlooking Spaniards were thoroughly absorbed and even a little joyed by the spectacle. But in no way was this a show put on for an audience, or certainly not an earthly audience. It certainly wasn't a display for the sake of tourism or the culture industry. The participants had gone to immense effort, There were many of them, each wearing an immaculate instance of the several varieties of costume. They proceeded in groups all identically attired. One assumes that they might actually enjoy the event, although they were almost all masked so it was impossible to tell. Almost all, with the exception of a large group of women in black. That part of the procession I understood immediately. I guessed them to be widows, and respected their sorrow and grace enough to stop my incessant photography. But there must surely be an element of sacrifice? Certainly for the many people involved in carrying the enormous wooden platforms that display figures and scenes from the life of Christ.

As they carried this vast platform they were swaying in time to the music.

Was this penitence? I am an atheist, but within a Protestant culture. I struggled to comprehend. Is there nothing like this in England? Some point of reference? Well I did once live in Lewes, a town famous for its procession. But in Lewes they don't venerate popes, they burn them, in an entirely British way.

The figure of Christ is actually quite disturbing (to an atheistic Protestant).

Two things were entirely clear. Firstly, the masks made me deeply uneasy. Not because the dramatically pointed hats evoke images of racism in the American South, one can easily get around that association. Rather, it's the reduction of humanity to an anonymous mass. The elision of the individual. The mass even included masked children. That feels threatening. But worse still is one particular image: men in black masks (rounded, and a little flat on top) carrying a wooden platform in the manner of pall bearers carrying a coffin. The connection is irrational and no doubt a sign of my complete lack of understanding. As I stood there watching this sight, I struggled to rid myself of an image from 1980's Belfast: IRA men in black masks carrying a coffin.

Black masks and gloves.

A second part of the dislay made sense. In front of a platform carrying a figure of Christ walked two men dressed as Roman soldiers, complete with spears. I thought they looked rather friendly, jolly even. Good chaps. The sort that you would meet down the pub. At least one could see their faces and hence their humanity. How very odd to end up siding with the bad guys.

The jolly centurion.

The procession circulated several times around its route, each time gaining in intensity and numbers. After what seemed like half an hour, it disappeared, perhaps returning back into the great gothic tomb of the cathedral, or perhaps just dissipating into the streets.

What we recognized as normality returned. The nice English speaking young lady at the Pension Berta gave us useful instructions as to where to find food. We of course forgot them almost as soon as we got outside. After some exploration, very good pizza were consumed, along with cerveza grande. And then on to the bars, many small fascinating places, usually displaying hams and other tapas ingredients. Here's an important tip for anyone visiting these parts. They drink beer in tiny measures, the size of whiskey glasses. There's no embarassment to be had in requesting a more substantial volume.

Martin admiring the display in a bar.

May 02, 2007

Dreaming of Jupiter by Ted Simon

Writing about web page http://www.jupitalia.com

- Title:

- Rating:

59,000 miles on a motorcycle is, in experiental terms, quite a journey. It is many times greater than that same distance travelled by car. And by air? – there is no comparison possible. There is always something special about travelling by motorcycle. Ted Simon has developed conclusive arguments on the subject: being exposed to the elements and the terrain, covering large distances with ease, experiencing sudden contrasts and juxtapositions, meeting people on their own more human terms, the constant physical and mental difficulty that intensifies experience, the ability to just stop anywhere at anytime, changing direction or just letting unplanned things happen, and quite often the humility of being a small individual on a big road. Speed and agility should of course also be mentioned. And danger? Yes, as Ted recently explained to me, that has to be part of it too. You’ll find all of these factors throughout Ted’s latest book, Dreaming of Jupiter. Both on the journey that it documents, and in the resulting book, they combine to make for an exciting and important read.

In 29 months, between January 2001 and June 2003, Ted piloted his bike, with varying degrees of skill and luck, on a journey of just that great intensive and extensive length. For a second time, he encircled the world and joined up countless distinct points and narratives just as he had in the ‘70s, resulting in the classic Jupiter’s Travels . On many occasions, chance and geopolitical forces conspired to pull him away from his planned route, which should have followed that of the 1973 journey. Afghanistan was out of the question, with consequences for Pakistan. The results are, however, still as interesting, and perhaps even more significant in providing us with a picture of how the world has changed in 30 years, and to where it might be heading. Perhaps the most important thread joining the two books together is that of migration, and the plight of the migrant. In 1973, I have claimed (and Ted says I’m on the right track) he was a migrant amongst migrants. Now he returns to the ever moving ever striving ever changing “unfinished world” (Ted’s great alternative description of the developing world). The intensity of it’s desires and frustrations is shocking. This book acts as a warning to the rich nations.

So there then are a few good reasons to read Dreaming of Jupiter. But there’s a lot more. Ted’s style, a master of the art of travel writing, sets these arguments within a thoroughly enjoyable context. There’s more humour than the first book. Characters and situations are drawn up rapidly, but without resorting to cliches and stereotypes. Add to that lots of action (including one of the most dangerous high altitude breakdown rescues ever), beautiful ladies, fun with the Allende’s, and a BMW R80GS, what more could you possibly ask for?

April 29, 2007

Riding the Ruta de la Plata, part 2

Follow-up to Riding the Ruta de la Plata, part 1 from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

See by motorcycle to Seville through rural Spain, part 1 for an account of the first day of this trip.

Day 2

It was entirely obvious, surely? The obstacle had first appeared as the boat drifted into Santander harbour; in the distance to the south west, but massive enough as to clearly establish psychogeographical dominance over the landscape; an attractor re-aligning the paths of south-bound travelers. For an expedition like ours, the possibility was irresistible. And yet I did not consciously consider a crossing at altitude through the snow until deep drifts began to appear at the roadside. To a simple English mind Spain equals sunshine, warmth, and near desert conditions. Concentrate that simple mind upon the task of keeping a heavily loaded GS bike upright and on track through some of the most “exciting” roads in the world, and there is no time for reflecting upon the absurdity of these preconceptions concerning the climate. Of course Spain has many mountains, some quite big. By the time we were at the top throwing snow balls, the sense of surprise was still overwhelming.

On our first day in Spain we had ridden a short way from Santander and into the Picos de Europa National Park. The following morning, mountain air and the sounds of wilderness accompanied breakfast and strong coffee in a nearby café bar. A pathway led from the campsite upwards to a viewpoint looking out over the valley. From the west, the Rio Cares surges through the valley. To the east it passes through a gorge in the limestone cliffs. On my 1/250,000 scale

When viewed from the side of the valley, the Cares River looks insignificant compared to the surrounding mountains. The camp site extends almost to the banks of the river, but not quite all of the way. Access is barred by a tall metal fence, with only one sturdy gateway. The fence says something about the true power of the waters. Even the Spanish, with their pathological disregard for health and safety, would not want unaccompanied children going anywhere near a river like this. A snapshot at this point would be misleading. Even close up it can look insignificant. Its real power is made obvious by the thundering sound that it produces as it travels at great speed through the narrow passage of its course. I guess that the snow fields at higher altitudes must be melting, adding to the volume and speed of water. Melting snow changes the character of a river; not just its power, but also its beauty. This would be hard to capture on film. Perhaps a professional photographer could match the colour adequately: a vivid turquoise blemished only by the occasional tree branch passing at speed. However, its

At the start of the day, with the sun rising rapidly into the gap between the overlapping walls of limestone along the zigzagging path of the river, light patches of fog are lifted upwards. A golden eagle soon followed them, finding and exploiting the day’s first thermal. We could hear it calling hundred’s of metres above us, far beyond the clanking bells of the goats on top of the ridge behind the camp. We would soon follow its example, and get out chasing the warmth of the day ourselves.

Westwards, the shape of the road already provided interest, through the small town of Poo (

A little beyond the centre of Cangas, we turned southwards into the Picos. Before going too far, I stopped to check the map. A twisty looking road was ahead. And yet I still did not realise just what we were heading for. We did know that this ride would be worth recording, and so Martin decided to try a new technique: with tape he attached a small Mini-DV video camera to the “beak” at the front of his R1100GS, using a small patch of foam to eliminate vibrations. After some more experimentation, a good recording was made, and the results are currently being edited.

Martin Conquers the Mountain

I admit that I am not a particularly fast rider. Also, unlike Martin, I didn’t have the incentive of a video camera strapped to the front of my bike. My ride through the Desfiladero de los Boyes was slow, cautious and concentrated on scenery. Martin, I’m sure, saw just as much of this amazing gorge as I did. But after waiting for me at our first stop half way through the gorge, it was impossible for him to hide his “where have you been for the last ten minutes” expression. Where had I been then? Pottering in amazement along a really great road. The Desfiladero runs along the wall of the cliff that rises almost vertically alongside the Rio Sella, through the Picos mountain range. At times it seems to head directly into the fearsome rapids of the river, only to twist back upon itself at the very last moment.

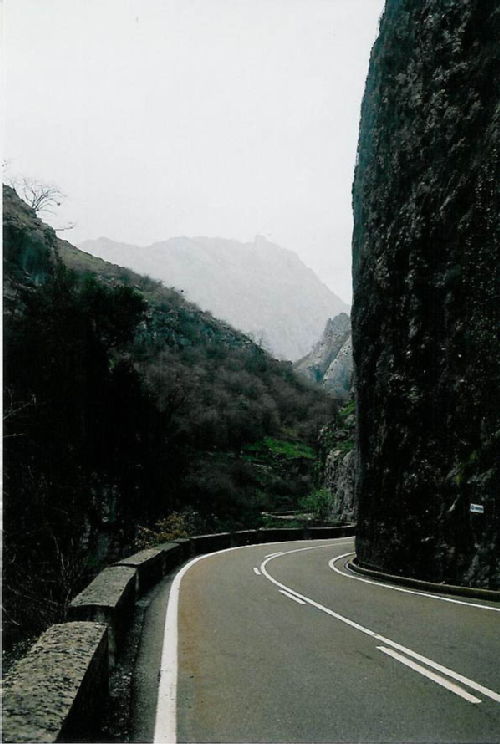

Between the wall of the cliff and its continuation at the edge of the road there seems to be barely enough space for two vehicles.

The narrowing sensation is accentuated by rock overhangs. The surface of the road is excellent, apart from where water runs across it at the base of mini waterfalls. Rocks and mud add further hazards, falling in large chunks often just out of sight in blind corners. Fortunately the traffic is light, especially given the local tendency to drive

Until this point the road stayed at quite low altitude. I still did not really think about the likelihood of it heading significantly upwards, despite its accent being marked clearly upon the map. Very soon after the waterfall, things changed. I didn’t really notice much of incline to start with. I did notice a change in the temperature. Down in the gorge, when away from the shadows, the sun provided warmth. Further into the mountain road, away from the river, I could feel the temperature dropping (perhaps by 1 degree per 100 metres, as is often stated). Wearing only summer clothes, with the air vents open, I began to feel a little chilly (though not that chilly, as I barely topped 30mph). The surface of the road started to deteriorate a little. Frost shattering does bad things to tarmac. We had already seen signs warning of ice. With water flowing across tight hairpin bends, some with adverse cambers, I regarded the warnings with some nervousness. Glancing away to the sides of the road, I started to see what looked like tiny glaciers up above. Just after the first of these mini glaciers, the snow poles started, at regular distances: striped with red and white to mark out heights, they act to provide a visual indication of the edge of the road when it is buried in deep snow. I considered a possibility: what if there were snow on the road ahead? Would we continue? Could we? I’ve ridden the GS in deep snow before, but on

As the road twisted upwards the snow deepened. I was now surrounded by a landscape that at lower altitude could only belong to mid-winter. As we reached the top of the pass, the views to each side opened out revealing snow fields stretching into the distance. The curves of the road became less extreme as we turned towards the sign marking the Peurto del Ponton pass at 1,280 metres. Just as we approached the top, an eagle swooped by (Bonelli’s eagle I think).

The road down was less technical, but still through snow. After a short distance the large Embalse de Riano reservoir came into view, looking more like a Norwegian fjord.

I passed quickly over a small bridge and then a much more impressive dam wall, to find Martin yet again waiting for me just outside of the town of Riano. We stopped to look at the scenery, and the snow.

A vulture drifted past. We agreed, this was a really great journey.

Where to next?

April 21, 2007

Riding the Ruta de la Plata, part 1

The Santander Landing

A Harley Davidson sounded the alarm, welcoming the slow approach of the still distant Spanish mainland by roaring out an un-necessarily raucous grumble from its perfectly polished show pipes. Had a fight actually broken out over his impetuosity, the short fat guy in a chromed open-face lid would not have stood a chance. Fortunately he understood the anger of the other hundred plus riders waiting on the bike deck of the ferry. He fumbled for the kill switch and abruptly turned his vanity off for a few minutes of humility.

It took longer than anyone had expected for the ship to dock and the way to be cleared for our procession onto Cantabrian dry land. While we waited, a family of hippies in a hand painted Luton van provided comedic interest. My old Beemer looked just as anachronistic, but instead attracted respectfully awed looks and comments from other riders, despite of, or perhaps because of, its age. Then finally a very tall man on a very tall bike, a KTM Adventurer complete will full overlander kit including jerry cans, led the way out into the sun. BMW GS overlanders were predominant, with several groups target-fixated on the dunes of Erg Chebbi, Morocco, or further: Mauritania, Senegal, perhaps even Cape Town. Martin (R1100GS) and I (R100GSPD) followed cautiously along the Paris-Dakar style caravan of bikes.

And then Santander received us.

This whole cavalcade of two wheeled adventurers, many riding machines capable of crossing deserts with ease, came to an instant and almost complete halt only a couple of hundred metres into its soon to be divergent trajectory: road works, of the kind that the Spanish do worst, right in the middle of town between the ferry terminal and the route out to the south. An interminable inching forwards followed. Politely, the mass of bikes edged its way through small one-way streets pretending not to have even a tenouos connection to the noisy idiot on the Harley Davidson. A hundred would be desert heroes. And one small girl in a flowery dress and matching pink helmet. What? How? Too late, she had already filtered through half the mass of bikes like a butterfly, barely noticeable. Spanish attitude. Breathtakingly audacious. And when she finally found no further gap, surrender was not an option – but the pavement was. Within seconds she was gone whilst we just sat there in amazement.

We did eventually break free, spewed out onto a badly pot-holed high street, as rough as a Saharan piste. One particularly large crater swallowed a quarter of Martin’s rear wheel. And then we reached smoother tarmac. I didn’t even bother trying to estimate the length of our imprisonment in the jam. “Head south” was my only thought. Martin no doubt shared this desperation to forget our first minutes in Spain. We filtered out onto the A8 motorway, and put a pleasing amount of distance between ourselves and Santander, heading towards Torrelevegas and a roadside café in order to get coffee, cakes and some kind of plan. The coffee was freshly ground and blasted excellence, as is almost always the case anywhere in Spain. It worked. I had an idea.

Why?

Two English chaps on old German desert racers. 2000 miles of road. Many petrol stops, and many, many more cups of strong Spanish coffee. One litre of high mileage Castrol GTX to keep the almost run-in valve gears and pistons ticking freely. And hours of concentrated riding. There had to be a reason, surely? There is always something special about travelling by motorcycle. Ted Simon has developed conclusive arguments on the subject: being exposed to the elements and the terrain, covering large distances with ease, experiencing sudden contrasts and juxtapositions, meeting people on their own more human terms, the constant physical and mental difficulty that intensifies experience, the ability to just stop anywhere at anytime, changing direction or just letting unplanned things happen, and quite often the humility of being a small individual on a big road. Speed and agility should of course also be mentioned. Rural Spain offers opportunity for all of this. We found it on the snow covered mountain roads, endless twisting gorges and passes, along great lakes and through beautiful national parks. But there was also something else, something very personal for me. Having now ridden over 50,000 miles on my old GS, it actually feels like home. Bolting on the panniers and filling them with camping gear accentuates the sense of being a “one man caravan” (in the words of Robert Fulton). I have spent a significant part of my life piloting that bike through all kinds of traffic, weather and news. The M40 in the snow. The City of London on September 11th 2001. Oxfordshire in full flood. The Paris Peripherique in the rain, smelling like the ocean. It provides a platform from which I have experienced the world, its many textures and colours. And then to sit on that familiar seat, look out over those old handlebars at somewhere as exotic as a mountain pass or the orange-tree lined streets of Sevilla attunes my perceptions, my sense of difference, place and time. To “be” is to experience difference, to move through a world of contrasts (subtle or abrupt), to differentiate. Motorcycling is a great way of being. That then is my reason for travelling in this way.

And Then Someome Turned the Volume Up

I think it all started with a blackbird, sometime after 4am. A tawny owl then asked repeatedly “who is there?”. Within a few minutes hundreds of different points around the valley and mountainside began to mark out intensive and extensive territories with a great variety of songs. The voices were mostly familiar, perhaps accented with a Spanish twist (birds do have regional accents, as has recently been demonstrated). A few sounds were entirely new to me – maybe an alpine chough? However, the overall effect, the pattern of their distribution, was entirely unfamiliar. Whereas the birds of Kenilworth Common always seem hemmed in by the surrounding urbanization, the symphonic arrangement in this big wide valley was much more expansive and free. Birds called from every direction, at many different altitudes. In my tent, not far from the fast flowing river at the centre, I was overwhelmed and sleepless. I didn’t mind at all. It was a testimony of the biodiversity and natural wealth of this place. I lay down with my tent open, listened to the sound scape, and recalled the previous day’s ride.

On our first afternoon in Spain we covered just a short distance. Riding westwards on the A8 dual carriageway, we had turned off at Peseus. A small road then led into the mountains of the Picos de Europa National Park, through Panes and a series of small villages. Out of season, much was quiet. The road narrowed and cut its way through overhanging rock. This was exciting in itself, but only just the start. In the distance occasional glimpses of snow covered mountains appeared and then vanished. Promising, but our first day would end at the excellent Naranjo de Bulnes campsite near Arenas de Cabrales, to be followed by one of the best dawn choruses I have heard.

Before sunset, some time was spent photographing skittish lizzards in an old tree trunk. With our tents established, we walked the one kilometre along the road to the village, past an impressive hydro-electricity plant piping mountain waters through humming turbines. Upon our return, the restraurant and bar was the obvious destination. Drinking beer like the sun parched Alec Guiness, we quickly established ourselves with the friendly natives. Dinner was had. Sardine-sized trouts grilled with chips for me. Pleasing.

That evening I made two seemingly incompatable observations. Several times an old man cycled past towards the village. He was dressed in green tweed, with a flat cap. Tall, thin and angular, he propelled the cycle with a mechanical awkwardness, but also an ease of ancient familiarity. Each village-bound leg of his circuit saw a surprisingly large bundle of firewood strapped to the rack at the back of the bike. Thomas Hardy may well have been the last man in England to witness such activities. But in Spain, as we were to discover, such rural manual labour is common. And then later, another very natural and rural scene. Wooden pitchforks. Cartwheels. Rough adobe materials. Images of woodland birds painted onto windows. Vivaldi’s Four Seasons wafting out of speakers in each corner of the roof. Scorchingly hot water piped in with the music. The ammenity block of the Naranjo de Bulnes campsite tries really really hard, and somehow manages to be quite charming. It certainly is well looked after; a welcome discovery for a tired motorcyclist.

Now read part 2 of this trip.

March 21, 2007

R100GS PD – latest progress

Follow-up to Balancing a Bing and other esoteric BMW motorcycle restoration rituals from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

After fitting a new throttle cable, I couldn’t quite get the carb setup correct. Worse still, one of the cable kept jamming, and then jumping out of the holder at the twist grip end. To get it sorted quickly, I called on Phil the Boxerman Hawksley, the renowned BMW specialist from Leicester. Phil did a service at my house, for a very reasonable fee. He set up the carbs perfectly, as well as tightening the steering bearings to prevent the bar wobbles that I had been experiencing.

Proof of the quality of Phil’s work came on a ride down to Dorchester (to see Ted Simon). The bike ran well. On the way back, after a fast motorway dash from the south coast, I stopped at a petrol station with the counter saying that I had done 220 miles since the last full tank. I would normally expect to have to put in around 28 litres for 220 miles. Efficiency can be as low as 43 mpg on an old airhead GS at high speed. It most often makes about 45 mpg. On this ocassion, I was surprised to find that it had used much less fuel than expected. The bike ran at around 50 mpg at high speed on the motorway. Well tuned carbs? And perhaps a change of engine oil: Castrol GTX rather than the usual Castrol GP.

Since then it’s had a couple of new tyres fitted by the very helpful Behind Bars trail bike specialists in Kenilworth. Metzeler Tourance as usual, although I am considering a change. They also did an MOT. It passed with no problems.

The last few jobs to do:

- use some new bolts to secure the pannier rails to the subframe;

- re-attach the sump guard;

- find a small box to put next to the smaller than standard Hawker Odyssey battery;

- mount the panniers and tank bag.

Lawrence in training to go RTW by motorcycle

Follow-up to Jupiter's Travels by Ted Simon – a really great book of travel or migration from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

Ted Simon probably wouldn’t mind (he let me sit on his R100GS), but the security guard certainly did. However Lawrence absolutely insisted upon climbing up onto the Triumph Tiger made famous in Jupiter’s Travels:

And here’s a photo of me on Ted’s GS:

The Long Way Round expedition by Charley Boorman and Ewan McGregor was a genuinely tough RTW, leaving many scars on this R1150GS Adventure, including some rather neat welding to the rear subframe carried out in Mongolia. Lawrence of course prefers the old Airhead R100GS, but was happy to pose next to Charlie’s bike:

Equipment list for Easter expedition

My GS will be loaded up with its full luggage set. That provides plenty of space:

- 33 litres in the Touratech Zega top box (TP);

- 46 litres in the left Tesch pannier (LP);

- 46 litres in the right Tesch pannier (RP);

- 45 litres in the Touratech V45 tank bag (TB);

- 2.5 litres in the built in glove box (GB);

- 1 litre in the underseat tool box;

- 35 litres in an Ortlieb dry bag (OB);

- some extra space on the rear seat for large/long items (RS).

A total of 208.5 litres of covered storage. If that were completely filled, and accompanied by 35 lites of fuel, it would most certainly be far too much. But that’s not the plan. Four rules apply when packing for motorcycle camping: 1. take all of the essentials; 2. keep weight to a minumum; 3. distribute weight low and evenly; 4. pack so that any item can be retrieved without every other item having to first be unpacked. Hence my approach is to have far more luggage capacity than I actually need.

Camping

- a lightweight one man tent with pegs (RS);

- tent mallet (can this be replaced with something smaller?);

- combined torch and tent-light;

- mini maglight;

- self inflating sleeping mat (RS);

- small pillow;

Wardrobe

- five pairs of boxer shorts;

- five pairs of socks;

- three t-shirts;

- one short sleeved shirt;

- swimming shorts;

- one pair of BMW summer motorcycle trousers;

- one pair of Heine Gericke Air desert motorcycle trousers;

- one Heine Gericke Tuareg armoured jacket, without Gore-Tex liner;

- one pair of Diadora motocross boots;

- desert boots;

- one pair of Heine Gericke brown leather gloves;

- one pair of Heine Gericke windstopper glove liners;

- BMW Sports Integral helmet;

- Hein Gericke Tuareg waist bag;

- four sets of foam earplugs;

Kitchen

- Coleman petrol stove;

- plate, fork, knife, spoon, cup;

- 2.2 litre Camelback water carrier;

- box of matches;

Bathroom

- one small towel;

- toothbrush;

- small toothpaste;

- soap;

- small medicine kit;

Office and photography

- watch;

- small digital camera;

- binoculars;

- Palm M515;

- Palm keyboard;

- mobile phone (check coverage);

- phone car charger;

- camera battery charger;

- BMW power socket converter;

- paper notebook;

- Nikon F50 SLR with 80-300mm lens;

- 35mm film;

Navigation

- Magellan Palm GPS;

- map measurer;

- compass;

- maps;

Bike tools

- electric tyre pump (RP);

- Ultraseal tyre sealant (RP);

- disc lock;

- security chain and lock (RS);

- wheel spanner;

- allen keys;

- screwdriver set;

- 1 litre of engine oil (LP);

Documents

- driving licence;

- V5;

- E111;

- insurance certificate;

- passport;

- credit cards;

- tickets;

- travel insurance documents;

- contact details.

February 11, 2007

The Road – motorcycle riding and writing by T.E. Lawrence

The Mint is an extraordinary but often overlooked book. Deliberately rough and forthright, it gives an account of the time spent by T.E. Lawrence as an ordinary cadet and airman in the RAF (hiding under the alias T.E. Ross). There is little joy or freedom in the book. The author seeks out the supression of self that is service, so as to demonstrate, amongst other things, the near moral bankruptcy of the British military post-WWI. However, amidst the depression and squalor, towards the end of the memoirs (and once posted to the much more salubrious Cranwell College), the following chapter stands out.

Lawrence had by this time (1925-26) become an aircraft engineer with experience and knowledge. He found something in this work that even surpassed his time amongst the leadership of the Arab Revolt. Fast machines and freedom. And most of all, motorcycles. This generated perhaps one of the best accounts written of a motorcycle journey. We are given the impression that this exhilerating ride is nothing but an everyday occurence. And no doubt with the fresh tarmac and empty roads of the mid-Thirties, it was just that. These days one rarely has a chance to experience the road in this way, and certainly not to duel with a Bristol Fighter above. Motorcyle safety has also improved somewhat. Lawrence’s Brough Superior, perhaps the 30’s equivalent of a modern Suzuki Hayabusa hyper-sports tourer, had almost no brakes, almost no suspension, and a hand gear change making engine braking a terrifying prospect. And yet it gave 52bhp – almost as much as my R100GS. The rider wore no helmet and no goggles. And certainly no kevlar body armour. And he still pushed it so hard that the bike lunged into a near fatal tank slapper.

Ten years later a similar event led to his death.

One of the greatest accounts of a motorcycle ride…

The Road

The extravagance in which my surplus emotion expressed itself lay on the road. So long as roads were tarred blue and straight; not hedged; and empty and dry, so long I was rich.

Nightly I’d run up from the hangar, upon the last stroke of work, spurring my tired feet to be nimble. The very movement refreshed them, after the day-long restraint of service. In five minutes my bed would be down, ready for the night: in four more I was in breeches and puttees, pulling on my gauntlets as I walked over to my bike, which lived in a garage-hut, opposite. Its tyres never wanted air, its engine had a habit of starting at second kick: a good habit, for only by frantic plunges upon the starting pedal could my puny weight force the engine over the seven atmospheres of its compression.

Boanerges’ first glad roar at being alive again nightly jarred the huts of Cadet College into life. ‘There he goes, the noisy bugger,’ someone would say enviously in every flight. It is part of an airman’s profession to be knowing with engines: and a thoroughbred engine is our undying satisfaction. The camp wore the virtue of my Brough like a flower in its cap. Tonight Tug and Dusty came to the step of our hut to see me off. ‘Running down to Smoke, perhaps?’ jeered Dusty; hitting at my regular game of London and back for tea on fine Wednesday afternoons.

Boa is a top-gear machine, as sweet in that as most single-cylinders in middle. I chug lordlily past the guard-room and through the speed limit at no more than sixteen. Round the bend, past the farm, and the way straightens. Now for it. The engine’s final development is fifty-two horse-power. A miracle that all this docile strength waits behind one tiny lever for the pleasure of my hand.

Another bend: and I have the honour of one of England’ straightest and fastest roads. The burble of my exhaust unwound like a long cord behind me. Soon my speed snapped it, and I heard only the cry of the wind which my battering head split and fended aside. The cry rose with my speed to a shriek: while the air’s coldness streamed like two jets of iced water into my dissolving eyes. I screwed them to slits, and focused my sight two hundred yards ahead of me on the empty mosaic of the tar’s gravelled undulations.

Like arrows the tiny flies pricked my cheeks: and sometimes a heavier body, some house-fly or beetle, would crash into face or lips like a spent bullet. A glance at the speedometer: seventy-eight. Boanerges is warming up. I pull the throttle right open, on the top of the slope, and we swoop flying across the dip, and up-down up-down the switchback beyond: the weighty machine launching itself like a projectile with a whirr of wheels into the air at the take-off of each rise, to land lurchingly with such a snatch of the driving chain as jerks my spine like a rictus.

Once we so fled across the evening light, with the yellow sun on my left, when a huge shadow roared just overhead. A Bristol Fighter, from Whitewash Villas, our neighbour aerodrome, was banking sharply round. I checked speed an instant to wave: and the slip-stream of my impetus snapped my arm and elbow astern, like a raised flail. The pilot pointed down the road towards Lincoln. I sat hard in the saddle, folded back my ears and went away after him, like a dog after a hare. Quickly we drew abreast, as the impulse of his dive to my level exhausted itself.

The next mile of road was rough. I braced my feet into the rests, thrust with my arms, and clenched my knees on the tank till its rubber grips goggled under my thighs. Over the first pot-hole Boanerges screamed in surprise, its mud-guard bottoming with a yawp upon the tyre. Through the plunges of the next ten seconds I clung on, wedging my gloved hand in the throttle lever so that no bump should close it and spoil our speed. Then the bicycle wrenched sideways into three long ruts: it swayed dizzily, wagging its tail for thirty awful yards. Out came the clutch, the engine raced freely: Boa checked and straightened his head with a shake, as a Brough should.

The bad ground was passed and on the new road our flight became birdlike. My head was blown out with air so that my ears had failed and we seemed to whirl soundlessly between the sun-gilt stubble fields. I dared, on a rise, to slow imperceptibly and glance sideways into the sky. There the Bif was, two hundred yards and more back. Play with the fellow? Why not? I slowed to ninety: signalled with my hand for him to overtake. Slowed ten more: sat up. Over he rattled. His passenger, a helmeted and goggled grin, hung out of the cock-pit to pass me the ‘Up yer’ Raf randy greeting.

They were hoping I was a flash in the pan, giving them best. Open went my throttle again. Boa crept level, fifty feet below: held them: sailed ahead into the clean and lonely country. An approaching car pulled nearly into its ditch at the sight of our race. The Bif was zooming among the trees and telegraph poles, with my scurrying spot only eighty yards ahead. I gained though, gained steadily: was perhaps five miles an hour the faster. Down went my left hand to give the engine two extra dollops of oil, for fear that something was running hot: but an overhead Jap twin, super-tuned like this one, would carry on to the moon and back, unfaltering.

We drew near the settlement. A long mile before the first houses I closed down and coasted to the cross-roads by the hospital. Bif caught up, banked, climbed and turned for home, waving to me as long as he was in sight. Fourteen miles from camp, we are, here: and fifteen minutes since I left Tug and Dusty at the hut door.

I let in the clutch again, and eased Boanerges down the hill along the tram-lines through the dirty streets and up-hill to the aloof cathedral, where it stood in frigid perfection above the cowering close. No message of mercy in Lincoln. Our God is a jealous God: and man’s very best offering will fall disdainfully short of worthiness, in the sight of Saint Hugh and his angels.

Remigius, earthy old Remigius, looks with more charity on and Boanerges. I stabled the steel magnificence of strength and speed at his west door and went in: to find the organist practising something slow and rhythmical, like a multiplication table in notes on the organ. The fretted, unsatisfying and unsatisfied lace-work of choir screen and spandrels drank in the main sound. Its surplus spilled thoughtfully into my ears.

By then my belly had forgotten its lunch, my eyes smarted and streamed. Out again, to sluice my head under the White Hart’s yard-pump. A cup of real chocolate and a muffin at the teashop: and Boa and I took the Newark road for the last hour of daylight. He ambles at forty-five and when roaring his utmost, surpasses the hundred. A skittish motor-bike with a touch of blood in it is better than all the riding animals on earth, because of its logical extension of our faculties, and the hint, the provocation, to excess conferred by its honeyed untiring smoothness. Because Boa loves me, he gives me five more miles of speed than a stranger would get from him.

At Nottingham I added sausages from my wholesaler to the bacon which I’d bought at Lincoln: bacon so nicely sliced that each rasher meant a penny. The solid pannier-bags behind the saddle took all this and at my next stop a (farm) took also a felt-hammocked box of fifteen eggs. Home by Sleaford, our squalid, purse-proud, local village. Its butcher had six penn’orth of dripping ready for me. For months have I been making my evening round a marketing, twice a week, riding a hundred miles for the joy of it and picking up the best food cheapest, over half the country side.

The full text of The Mint can be found online.

February 04, 2007

Why travel by motorcycle?

Follow-up to Jupiter's Travels by Ted Simon – a really great book of travel or migration from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

Because things like this happen…

Arriving at a hotel in Peru, no doubt looking somewhat worn out by a hard ride across South America, Ted Simon is pleased to be given a discount:

‘Por essos que llegen en coche, ochenta. Pero essos en moto son muy hombre,’ said the clerk with a grin. In other words, car drivers pay the full rate but there is a discount for heroes. p.288

Heroes deserve discounts!

January 22, 2007

Balancing a Bing and other esoteric BMW motorcycle restoration rituals

Follow-up to Exhaust[ion] from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

Engine cleaning

The most important task was to clean up the engine casings. I’m not trying to create a show bike. Rather, I needed to get rid of the thick layer of road grime and old oil, so that I will be able to spot fresh oil leaks more easily. Whilst doing this, I gave some of the surfaces a polish with Autosol and wire wool – yes wire wool – the old airhead GS engine is almost bare alluminium, so can be treated a little more roughly than a modern bike. The cylinder cover fins were scrubbed even more aggresively, using a long bristled steel brush. A build up of grime in the fins may actually lead to overheating – the engine is air-cooled, so needs to transfer heat outwards as efficiently as possible.

Frame

With all of the crash bars and bash plates off, I could also clean the frame, remove a substantial amount of rust, and repaint. I did an acceptable job of saving the metal from further damage in the short term, but it looks as if it will need a professional treatment soon. Powder coating will be worth it. The lower fork bridge and the battery cage also scrubbed up well, and now sport a shiny black coat of Hammerite. Less sucessful was my attempt at repainting the valve covers with high-temperature paint. I think i’ll just strip them back to the silver alluminium, and maybe even replace the left hand cover with a Touratech cover (with built in oil filler). As for the severely battered right hand engine bar, having taken the brunt of most of my off road falls, I can’t save it but haven’t yet sourced a replacement.

Exhaust

As can be seen from the photo, the downpipes were replaced with ones bought for a bargain £40 from Motorworks . Part of the old pipes seized solidly into the y-piece, necessitating its replacement with a new Keihan pipe from Motobins – £130 – rather expensive, but it is nice and shiny. The silencer still seems fine. I can’t find a replacement for the excellent Laser Produro, so will keep it on for as long as possible.

Rough running

Replacing the heavily corroded left hand spark lead has been just the first step in sorting my engine problems. The bike started up first time, ran well for a while, but then started running roughly. Prodding the carb mechanisms revealed that they were sticking badly: perhaps the most common cause of engine problems in the airhead beemers. The big Bing carbs are completely exposed to the elements, sitting just behind the flat twin boxer cylinders as they stick out the sides of the bike. The external throttle and choke mechanisms, if run in the British winter, soon fill up with black gritty road grime. Rough running, over fast idling, and even serious engine damage (like the burnt out valve that I once suffered) may result.

To solve the problem I removed each carb from between the engine and the airbox, turned it around so that I could access the dark side of the carb, and scrubbed it well. This photo illustrates a clean unit:

Notice the damaged throttle cable. I replaced it with a new OEM BMW cable. Once reassembled, the throttle and choke action was much improved. I had expected that when starting the engine the carbs would be well out of sync and the idling speed set incorrectly. Amazingly I had guessed almost the correct settings, so have not yet seen the need to use my vacuum guages and the ancient Bing balancing ritual. My plan is to get the bike to an airhead boxer specialist next Saturday (Euroclassics of Northampton) and get the carb settings checked, as well as some good advice on what else needs to be done. This should hopefully confirm my belief that it will be ready for a tour southwards (Spain, Morocco?) at Easter.

All going well except for a puncture. To my great surprise when I wheeled it out of the garage on Saturday the front tyre was flat. It’s a slow one, and there’s no sign of a nail or other object, so perhaps there’s a problem with the seal or the valve. I’m tempted to fit some TKC80 off road tyres, just in case Martin (R1100GS) and I make it to the Merzouga.

More news next week.

January 16, 2007

Jupiter's Travels by Ted Simon – a really great book of travel or migration

- Title:

- Rating:

A very great book, many agree on that. But what kind of book is it? For a while I thought that I could take an interest in the travel writing genre, having enjoyed and learnt greatly from Jupiter’s Travels. I read a lot of travel books. Some are impressive in their own ways. But I remained disappointed. Then recently I read Ted Simon’s classic for a fourth time. Half way through Africa, the second of the journey’s six continents, my mistake became obvious. It’s not really a travel book at all. It is a book of migration, diaspora, escape.

You can, if you want, read Jupiter’s Travels as a great adventure story, which it certainly is. It’s a good, if not the best, motorcycle travel book. If that’s what you want, then just read it. But there’s more. Much more. This is my response to the first two chapters…

Conventional travel books are essentially long postcards dispatched to home. ‘Wish you were here’. Or in some cases, ‘bet you’re glad you’re not here’. Eventually, as we know right from the outset, the writer gets back to the home that was always there. But there is never really a homecoming, or even a home in Jupiter’s Travels (the sequel to Jupiter’s Travels was at one point published as Riding Home, but is now entitled Riding High). Yes, the world was encircled in Simon’s tightening noose. The two ends of the journey, start and finish, twisted around each other on the return to Coventry. The rope tightened…but around thin air. The world had slipped away and refused to be suffocated.

A life, the journey, continued, jumping back and forth across the surface of the world, California, India, France, Romania etc. It continues even now. Part Jewish, part German, part Romanian. Human shrapnel dispersed the First World War and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. Culturally English, living in America, perhaps even a little bit Indian (spiritually). Part this and part that: Ted Simon – like half the people in the world, on the move, looking for opportunity and experience. A migrant amongst migrants.

Why does this matter? What difference? Travel writing has a recurrent fault: the writer/traveller never really lets go. The journey remains as an interlude within the career. The people and places that are documented never rise above the status of curiosities. The events, the interruptions, are mere diversions. Reality, coincidence, only distracts from the essence of places, or rather landmarks, represented as recollections, travellers tales, postcards, ideals and ideas. But the world is actually full of migrants and coincidences who, to the travel writer, may seem incidental, never true to a place. The vast majority of people in or from the developing world are migrants. Accident, the interconnections between the unstable and shallow surface of things, is the real. Real places, real experiences, which may seem permanent and eternal to the travel writer, are in fact transitory and temporary constructions of coincidence. History (human and natural) proves this, although the power of the travel industry transforms the mistaken apprehensions of the travel writer into self-fulfilling prophecies: places become more like the stories that are told about them. The importance of Ted’s book is that he actually becomes a migrant (or perhaps always was one), and is thus able to encounter the world and its people on their own terms. Being a migrant amongst migrants allows the writer to value people, places and events. I can’t think of single location in its 447 pages that could ever become a new tourist attraction. They are all far too real and minor. Many of them no longer exist, having been swallowed up by development, decay or dessertification. An epic book of an epic journey, never serving the imperialistic colonising travel industry. The philosophers Deleuze and Guattari invented the term ‘minor literature’ to describe writing that comes from migrants and under-dogs. It may still be great literature. Kafka they say is minor literature. But it doesn’t come from the dominant major culture within which it swims. Jupiter’s Travels is part of a related genre: minor travel literature. This is how it’s done…

63,000 miles on that feeble little machine! Hacked together from the Meriden parts bin, amidst a near-death experience for the old Triumph company, and then the total collapse of Midlands industry. Only hours south from that miserable place the crankcase spewed its store of lubrication across the road. Failure in the 1970’s was just part of the plan, quality control to be undertaken by the customer out on the road. It was rebuilt and the journey stuttered into life again.

Half way across Lybia and the engine had already started to self-destruct. In those days a spare piston was just part of any long distance rider’s toolbox. The ability to strip and rebuild an engine somewhere out in the African bush? Taken for granted. And finally, just south of Louis Trichardt in SA (where by coincidence I once broke a gearbox) valves dropped, a sleeve corrugated, rings warped and the piston seized:

“The broken metal had penetrated everywhere and again I was struck by the force of the coincidence that all this havoc had been wrought virtually within sight of Johannesburg”. p.173

The end clearly being both nigh and divinely ordained, any normal person would have bailed out. But Ted Simon is no ordinary person. He still had another four continents to crash through (with increasing grace and understanding): interrogations by the Brazilian police, vast landscapes to carve out, portraits to draw of hundreds of people in detailed miniature, love and ideals, horrible accidents (when fishing not riding), India, and an encounter with destiny.

Apparently, a machine only works when it breaks down. Or as the journey demonstrated:

”...the interruptions were the journey.” p.132

And what a machine! A literary machine, an intellectual machine, a desiring and sometimes paranoiac machine. All wired into the bike, the journey and its improbable rhythms:

“The movement has a complex rhythm with many pulses beating…all this metal in motion, amazing that it can last for even a minute, yet it will have to function for thousands of hours [like a human heart]...Through all these pulses blending and beating I hear a slow and steady beat, moving up and down, three semi-tones apart, a second up, a second down…Is it the pulse of my own body intercepting the sound, modifying it with my bloodstream?” p.28-29

The rhythm is both dependable and on the edge of breakdown. Like consciousness itself. It acts as a single line through time and space against which the world is measured. Marking time both produces and absorbs intensity. And then looking outwards from this beat, time and its extension in space is conquered:

“From Tripoli to Sirte is three hundred miles, and I’m really flying with the engine singing for me and everything rapping along nicely. There’s a lot of rain, but I’m less nervous of the wet now, on tar at least. The land and sea lie flat out forever, and I can see the weather coming maybe fifty miles ahead. I have never seen so much weather. I can see where it begins and where it ends; I can see the blue sky above, and the approaching storms and then the good times beyond. Remarkable. Like having an overview of past and future. I am a world spinning through visible time.” p.53

And at the end of Africa:

“I have just ridden that motorcycle 12,245 miles from London…As I think about it I have a sudden and quite extraordinary flash, something I have never had before and am never able to recapture again. I see the whole of Africa in one single vision, as though illuminated by lightning.” p.183

He is of course that lightning flash, connecting thousands of disparate and ever moving points across the vastness of Africa. That interconnection of surfaces is then his essence, the essence of the migrant. He qoutes Gerard Manley Hopkins on the strangeness of being (he revived the medieval philosophy of Duns Scotus and its notion of coincidental but non-decomposable, un-dissolvable uniqueness and identity: essence through accident).

But how many people need to go through 63,000 miles of pain and pleasure to get a home, to clarify and solidify their own substance?

Why? What motivation? There was something demonic, possessing – not just the fire in the cylinder bores, although the bike is important in itself. Rather some circuit in Ted himself, circulating round and round iteratively, sometimes whirling like a tornado of doubt and fear sucking events into its core. At times the force is intense, a whirlwind ripping across the surface of the Earth. Is the journey there to satiate and extinguish that force entirely? Therapy? Or perhaps travel of this kind, and its writing, is a learning process: the question being how to tame and harness that power. How to live successfully as a migrant? Perhaps that could help us with our conflicts and confusions? In Tunisia the effects start to look dangerous. In Libya and Egypt, the raging Yom Kippur war perhaps distracts the police and the people from the effect. And then in Egypt it comes back even more fiercely:

“Could turbulence and change be ‘carried’ and transmitted like a disease? I knew I had brought excitement into those three lives, but the news from the front was always good. I wondered, unhappily, whether I was destined to leave a trail of grief and misery behind me too.” p.74

This is the fate of the migrant. But by the end of Africa, enough has been learned upon which to form a new way of being a mobile difference engine on the road. That is the art of the migrant. However for a while, when physical movement ceases, these lessons no longer make sense. The journey must be taken up once again. And then by California, the traveller and the reader are to a much greater extent able to stop the extensive spatial movement through space while still retaining an intensive movement on the spot, still governed by the habits of a well practised traveller. At this moment relations with other humans are able to deepen and stabilise, at least for a while. Ted finds love, but as the interconnection, intertwining of a set of mobile and tensile surfaces, soon to spring back into life: Australia and Asia.

Coming soon…

Robert O'Toole

Robert O'Toole

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading