‘Have you forgotten that I am one of you?’: Returning Mau Mau in late–colonial Kenya

Writing about web page https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/hrc/confs/homecoming/

In this second blog post relating to the HRC conference on Homecoming after war, the co-organiser, Niels Boender, a third year PhD student in History, outlines one aspect of his research and how it relates to the conference.

With these words, ‘Have you forgotten that I am one of you?’, the former Kenyan freedom fighter Gucu Gikoyo lambasted his neighbours, who were forcing him to confess his involvement in the anti-colonial Mau Mau movement (Gikoyo 1979: 246). His bitter and tortured experience of return after time in British-run detention camps, as all homecoming stories do, connects violent conflict and detention to the post-war world. In Kenya’s case, the post-war transition was also the transition to independence. The post-colonial state would be shaped in large part by the afterlives of the Mau Mau insurgency; these are best understood through the lens of homecoming. This short blog uses the story of Gikoyo, recounted in his 1979 memoir We Fought for Freedom, to trace how a perhaps unexpected moment of homecoming can expand our understanding of post-war return as a significant historical process.[i] Opening the door to more literary and political readings of such memoirs, this is a sample of the kind of subjects we would expect to be discussed at the conference.

Gikoyo, like so many young and uneducated Kenyans, took to the forests in the face of colonial racism, police brutality, and landlessness. Far from claiming any leadership role, he admits he was a simple soldier who had been tasked with killing informers. Like so many that went to fight in the forest, eventually his luck ran out and he was captured by British colonial forces in 1955. Captured while travelling away from his unit he was not tried and executed like so many fighters (1,099 were hanged under judicial procedures), but instead was despatched into the ‘Pipeline’: the archipelagic system of detention camps in which torture and confession were regularly employed to ‘rehabilitate’ Mau Mau suspects. In his memoir he testifies to the fact that he was repeatedly beaten with a club, flogged, and forced to confess taking the Mau Mau oath. As part of his interrogation, he was taken back to his home village. There he witnessed the consequences of the colonial state’s counterinsurgency campaign, which involved herding hundreds of thousands of Gikuyu into carefully planned ‘Emergency Villages’. A curfew had been imposed, houses had been ransacked, and six children had already died of hunger and disease. He wrote: ‘I was deeply moved by the sight of the people who had withered and lost all life and lustre through hunger’ (Gikoyo 1979: 227). The local villagers, knowing of Gikoyo’s involvement in several murders, called on him to confess them. One elder said to him: ‘If you were willing to give your life for the salvation of this country, give it now so that the children, women and elders of this place may be saved’ (Gikoyo 1979: 227). Gikoyo did not relent and was eventually released in April 1958 without confessing to murders he had been accused of.

As he walked from the detention camp, ‘a master of [him]self, [he] thanked God for guiding me in the battle of wits which I had never fought before and which, through his grace, I had won’ (Gikoyo 1979: 235). However, his ordeal did not end upon his return. The continuing State of Emergency forced him to report daily to a local official and everyone in his village had to go through back-breaking communal labour, which was made especially difficult by a testicular disease he had got after being flogged in detention. Soon he fled his village for the colony’s capital, Nairobi, where he fell in with several other ex-detainees. Without residence or work licenses, they were forced into criminality, committing armed robberies, and soon he was back in prison.

Over the coming months he would repeatedly escape and be returned to prison. In his brief moments of freedom, he was especially angered by his village’s refusal to help him. He lamented: ‘Have you forgotten that I am in my own country now [for] which many of us have given our lives?’ (Gikoyo 1979: 246). He was frustrated by the way in which the counterinsurgency campaign had transformed his community and turned them against violent nationalism. Gikoyo would continue to embrace a militant vision of Mau Mau activism, even as the Emergency came to an end in January 1960. He formed a new gang of eight ex-detainees which raided European homes with the intention of acquiring firearms. Their plan was to ‘organise bands of terrorists to harass Europeans until such time as they gave up and handed over this country to an African government under our dear leader, Mzee Jomo Kenyatta’ (the alleged Mau Mau leader who remained in detention) (Gikoyo 1979: 261). Their raids of European houses called forth massive police action by the colonial state and only after a shootout in the Nairobi suburb of Makadara was his gang detained, all sent to ten years hard labour.

It was not until October 1969, almost ten years later and six years after Kenya’s independence, that he would be released. His ‘dear leader’ Jomo Kenyatta became the country’s Prime Minister in June 1963 but never offered an amnesty for Gikoyo or his compatriots as his crime was not deemed ‘political’ or in the service of anti-colonialism. A Government policy of ‘forgive and forget’ towards Mau Mau also meant his service in the forest would not grant him any special treatment. Even after his release in 1969 he felt unwelcome and unrewarded. He found a country that had not fulfilled the promises of the anti-colonial struggle, reminding the rich ‘that their joys are the result of much suffering and death’. As Mau Mau, their ‘role has not always been appreciated and the dark records are still held against’ them (Gikoyo 1979: 324). He stayed ‘unrecognised, having neither land on which to make a living or trade to follow’ (Gikoyo 1979: 325). Especially this final peroration ought to be read in the context of Kenya’s late 1970s political crisis when writers like Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o and politicians like Bildad Kaggia were attacking the post-colonial regime in part for its failure to live up to the promises of Mau Mau. The latter helped Gikoyo to edit and translate his memoirs from Gikuyu to English.

This account of a tortured, fractured, and problematic homecoming is symptomatic of civil war, states of emergency, and colonial impunity. Counterinsurgency efforts by the British Army and colonial administration had fundamentally transformed the ‘home’, both physically through villagisation and land reform, and emotionally by forcing a community to turn on its own fighters. Physically broken, unrepentant, and without a programme for economic re-integration, fighters like Gikoyo quickly re-mobilised. The fine line between revolutionary activism and criminality was effaced by the problematic process of homecoming. Government-supported efforts at reconciliation between opponents and supporters of the Mau Mau precluded any serious attempt at repairing colonial-era injustices and leaving a bitter legacy for the coming decades.

Like all papers at the forthcoming ‘Homecoming after war’ conference, this is but one example in a constellation of such stories. Gikoyo’s memoir does however open us to exploring unconventional times and spaces when trying to understand post-war transitions. Humanities-based approaches can break free from normative and prescriptive straitjackets attempting to understand post-war ‘disarmament, demobilisation and re-integration’, embracing the complexity of stories like Gikoyo’s. Much more can be done using comparative and inter-disciplinary approaches, even with this specific Kenyan example.

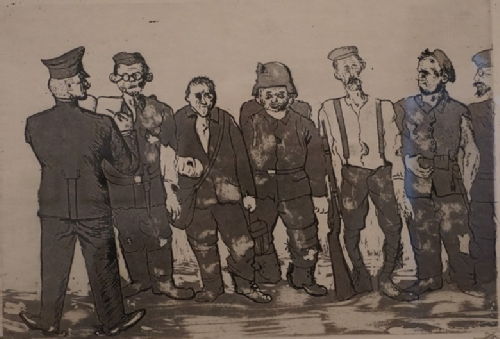

A suspected Mau Mau fighter is taken to interrogation by a British serviceman, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, MAU 864, Accessed 10/11/2022:

https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205191325

Sue Rae

Sue Rae

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…