All 10 entries tagged Kruger Park

No other Warwick Blogs use the tag Kruger Park on entries | View entries tagged Kruger Park at Technorati | View all 86 images tagged Kruger Park

August 28, 2008

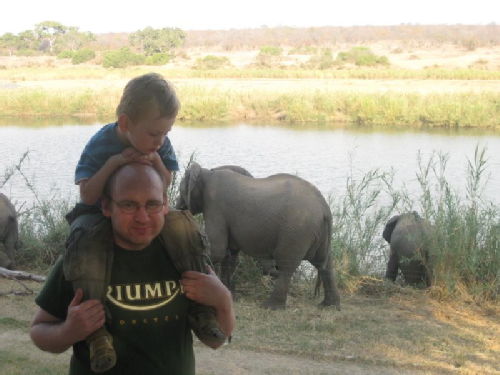

Shimuwini elephants

Shimuwini Bush Camp, Kruger National Park. A herd of elephants feeding on the reeds along the river, right next to the path at the bottom of the lawn. The elephants were in a relaxed mood, even though there was only a low fence between us.

More about visiting the Kruger Park.

October 06, 2007

Five good places to visit in Gaborone, Botswana

Follow-up to Botswana's finest chefs from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

Update: there’s a great new place in town – the No.1 Ladies’ Opera House.

1. The National Museum and Gallery

The museum has recently been renovated with many imaginative displays that illustrate the history, culture, geography and wildlife of Botswana. Highly realistic models and reconstructions are used. Traditional lifestyles are depicted with lifelike models of people (this really got Lawrence confused). Best of all are the models of animals and their habitats. An excellent way to learn.

Lawrence and the lions display (click to enlarge)

Looking at a reconstructed village scene

The museum also houses a gallery, used for displaying the best of current craft works from around the country (many for sale). There are ingenious sculptures, fine basket works, clothing, and much more. Another room hosts temporary exhibitions. In August 07 we saw some great paintings of anachronistic scenes from Botswana life, such as rondavels with satellite dishes.

2. Sanitas Garden Centre and restaurant

See the magic work of horticulturalist Dr. Gus Nilsson and his team of gardeners. Visit the best restaurant in Botswana. Chase the cheeky vervet monkey around the big wooden adventure playground as part of a big group of semi-wild african children. What more could you ask for? Sanitas is Gaborone’s best outdoors attraction. Visitors to Gaborone will probably not want to buy plants, but the displays are interesting in themselves. Use the garden centre as an opportunity to become familiar with the indigeneous flora and its preferred conditions. You may want to buy some of the garden ornaments on sale, such as metal animal and bird sculptures.

A useful coding system is used in the garden

3. Mokolodi Nature Reserve

Mokolodi is about ten minutes drive from Gaborone, along the Lobatse Road. It is a small nature reserve, with largely educational intentions. Non-members can tour the park on an official game drive. Other activities include meeting the orphan cheetahs, rhino tracking, bush picnics, and horse riding. Members can drive around on their own.

My family and other rhinoceroses

Poking a pile of rhino dung with a stick

Drought: normally this would be a lake not a pond

Drought: even the warthogs are being artificially fed

4. Gaborone Game Reserve

600 hectares of land right inside the city. Gaborone Game Reserve offers a chance to see some of the animals typical of the kalahari. Perhaps more significant is the bird life attracted to the large and smelly sewerage ponds that are part of the reserve. Spectacular sightings are certain. Even flamingoes and pelicans are possible.

Lawrence hiding from rapidly approaching zebra

The zebras in the park have an awkward habit: they will put their heads through an open car window in search of food. I once had one chewing the steering wheel. This time I got the window closed in time. Lawrence was amused to watch it licking the window.

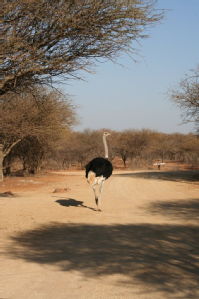

Ostrich burying its head to avoid the smell

5. Garden of the Grand Palms Hotel

Eat nice food. Drink underneath shady trees. Watch water birds in the small lake. Swim in the hotel pool. There’s even a children’s play area.

October 04, 2007

How to have a great safari at an affordable price

Which country?

Quick answer: South Africa.

Each of the five main southern African countries has its own slightly different wildlife and tourism infrastructure, offering something a little different to the others. The best developed of these, and of most interest for a first-time safari (or a family trip) is South Africa. Years of political isolation encouraged the further development of an already excellent internal tourism market. For over a hundred years the government and the people have taken pride in and enjoyed a large network of state run national parks. These parks offer an ideal combination: some of the world’s best wildlife and environments, along with brilliantly designed, professionally run and affordable accomodation. There are three major parks boards: SANParks (countrywide), Kwa-Zulu Natal Parks Board, and Cape Nature. Each of these provides efficient booking services (we recommend booking through email, and then confirming and paying a deposit on the phone).

Alongside these many great parks, South Africa also has many private game reserves. Foreign tourists are usually booked into these at great expense. Although they may offer luxury, the much cheaper national parks give a far superior wildlife experience – if you know what to look for.

Of the South African parks, the massive Kruger Park is the best first-time destination, followed by Hluluwe-Umfolozi in KZN. The Kgalagadi (Kalahari) Transfrontier Park stradling the Botswana border offers a very different but also very special desert wildlife experience. South Africa has the additional advantage of the Indian Ocean, making it possible to combine a safari (for example in KZN) with a beach holiday (the KZN coast). Guest houses, booked when you arrive, are the best option for coastal accomodation.

I will write about the other southern African countries soon.

Park fees

There is a daily rate for every visitor to the national parks. This is usually under £10. Compared to the cost of visiting a zoo in the UK, that’s a bargain. The cost can be reduced further by buying an annual membership. SANParks (for the Kruger) offers the WildCard (I think that is around £100 for a family for a year).

What accomodation?

Quick answer: self catering cottages in South African national parks (£20 to £125 per cottage per night).

The national parks in South Africa, Zimbabwe and Namibia provide ‘rest camps’ of various sizes, with a range of reasonably priced accomodation. The rest camps have shops, restaurants, museums, swimming pools etc. Accomodation options are:

- Camping with own tent (usually excellent, with good ablutions) – very, very cheap.

- Pre-assembled walk-in tents.

- Rondavels (small round cottages) with modern bathroom and kitchen – from £20 per cottage per night.

- Guest houses (larger cottages with a lounge, kitchen and several bedrooms).

- Rentmeister donor cottages (big luxury cottages with own grounds, sleeping 8-9 people) – around £125 per cottage per night.

Barbecues (braiis) are provided everywher. Linen and kitchen utensils are included. The bigger cottages may also have a cleaner (who can do laundry and car washing for extra). In the Kruger Park, further options are available. Especially good are the much smaller ‘bush camps’, often with only 10-15 well equipped medium sized cottages. The ‘bush camps’ simply offer a very peaceful and natural experience without shops and restaurants. When staying in a bush camp, you must take in all of the food that you require. Many of the parks now also offer a range of wildreness trails, along which participants are guided over several days walking or cycling, and camping out over-night.

Outside of the national parks, South Africa must also be commended for its thousands of excellent guest houses – they are everywhere, and almost always offer a high standard at a low cost.

Transport

The air fare from the UK is the single biggest expense. Avoid British Airways, for the usual reasons, but also because by flying on SAA the largest share of your tourism £££s goes into the SA economy. Plus, the food is better. Expect to pay around £700 to fly direct, less to go on a long indirect flight.

Once in southern Africa, there is a good network of internal flights. The SAA subsidiaries SA Express and SA Airlink fly from Jo’burg to towns near to national parks. A recent one-way flight for two adults and a child to Phalaborwa on the edge of the Kruger cost us only £60. A recent return flight from Jo’burg to Cape Town on the BA subsidiary Comair cost me £100 (but required booking by phone).

On the ground a car will be essential. In SA you can make-do with an ordinary hatchback or saloon (get air-con), for around £150 a week from any of the major hire companies. These will usually have a limited mileage agreement, but that is fine if you are just pottering around a national park. Cars can be collected from the airports near to the parks. For game viewing, a taller vehicle is better. We recently hired a Honda CRV 4×4 (a soft-roader) over 10 days for £250 from National Alamo – this was perfect. Book online.

There are also several companies that specialise in hiring out fully equipped safari 4×4s and camper vans. I’m really not convinced that such a huge expense is necessary. A serious 4×4 is only needed for very remote locations like the Richtersveld (not recommended unless you are really experienced). And camper vans are rendered obsolete by the great range of camping and cheap accomodation available.

Activities

Once inside a South African national park, there is a great range of activities on offer, either DIY or organised by the park staff. Here are some options:

- Inside the camp – there’s always lots of wildlife to see, including birds and often animals – plus most camps have view points allowing you to watch animals in rivers and water holes.

- Swimming – the bigger camps have swimming pools.

- Restaurants and cafes, often with views.

- Museums and displays – the elephant museum at Letaba is the best.

- Self-drive – just potter about in your own vehicle on the park roads looking for wildlife.

- Picnic sites – in the Kruger there are several picnic spots in which you can get out, wander around, and make your own food. They usually have gas-skottles for hire cheaply.

- Official game drives – with a trained guide – at the larger Kruger Camps, these take place in un-attractively large trucks (around £7 per person), the bush camps use smaller Hilux based vehicles.

- Morning drives.

- Sunset drives.

- Night drives – using powerful searchlights to see night time animals and activities – good chance of leopard in the Kruger Park – the bush camps use smaller vehicles.

- Guided walks – in small groups with a trained guide, expect to get close to dangerous wild animals (around £10 per person).

- Cycling – increasingly popular guided tours.

- Canoing and boat trips – in some parks.

- Specialist drives, looking at trees, birds, stars.

- Sitting by the cottage resting.

What is there to eat?

South Africa has great food. Rest camps have cafes and in the evenings good restaurants, usually with game meat and classic african dishes (bobotie, poitje stew), and often as unlimited buffets. Prices are reasonable, expect three course for under £10.

But eating in restaurants is missing the point. SA is the land of the braai (barbecue). Every cottage has a kitchen and a braai stand. Buy meat in the camp shop (often game meat, or the best imaginable beef). Cook it on the braai whilst drinking good cheap wine or Castle beer. Relax and eat outside, watching the sunset. That’s it.

When to go?

For the Kruger Park, on the north eastern lowveld (low country), the dry season is during our summer. It’s cooler, but still mild. Most importantly, the bush is less thick, so it is easier to see the animals. They may also be more concentrated around rivers and water holes. August is particularly good. Further into the centre of the country, on the highveld, the dry season is accompanied by cold (sometimes freezing). Cape Town is often windy and wet, but warmer for swimming at Christmas. The west coast reverses the rain patterns, with rain during our summer bringing our spectacular wild flower fields.

Surely there are problems?

Yes, but not really many. I’ve had worse illnesses on holiday in the UK, and never experience crime in SA (and i’ve been to Cape Town and Jo’burg). Here’s a list of the more likely problems:

- Dehydration – this is a real danger, and the one that has come closest to hurting me. Drink bottled water constantly. Watch out for salty tap water (I once collapsed with heat exhaustion after drinking salty water at the Makgadigadi Pans).

- Road accidents – South African driving standards are appalling. This has proved to be a major threat to tourists, however, there is a low speed limit inside the parks, which is actively policed.

- Bee and wasp stings – be prepared, carry Waspeze.

- Malaria – in the wet season (Christmas) use Lariam or another powerful anti-malarial, otherwise the Kruger and much of western and central SA is fine.

- Hepatitis – my mother had a bout of this after visiting Botswana, possibly caused by contaminated salad. Be choosy. Only eat uncooked food in places that you really trust.

Are the animals dangerous?

No, not at all. If you follow the rules and respect the animals you will have no problems. Unlike Botswana, SA camps have sturdy fences. If you get out of your car to photograph an elephant bull, expect to get trampled.

October 02, 2007

Botswana's finest chefs

Follow-up to My Family and Other Primates, Kruger Park 2007 Part 6 from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

“Dullstroom” – what a great name for a dorp in the middle of knowhere. I suspect that it is actually a little misleading. I bet there’s excitement if not intrigue to be found along its dusty dry streets. Well at least the fishermen are happy, the game fish growing large in the fresh and lively waters of the area. Several monster specimens are displayed around the bar, preserved in cases. A smaller but much more edible individual was served up on my plate. Possibly the best wild trout that i have eaten.

A comfortable night’s rest was had in an apartment at the Courtyard Hotel in the Arcadia district of Pretoria/Tshwane, followed by a short drive through the Magalisberg Mountains, across the Marico, and home to Gaborone, Botswana.

And the goat is served (ckick to enlarge)

And what of Botswana? Somehow it has acquired a reputation for dull food. Our friends Peter and Johanna are working hard to disprove that claim. The kalahari being goat country, they prepared and cooked a fat juicy leg, marinated in garlic. Fantastic! When slaughtering their own goat, they discovered an extraordinary world of beaurocracy, so now they prefer to buy their meat at JT Butcheries. No matter, it was perfect. Goat is a fine meat, with more depth to its flavour than all but the finest lamb. And yet even in Botswana it is known through the euphemism of “mutton”. At the Taj Indian restaurant, for example, many great goat curries (not curried goat) are served, amongst their other nice dishes.

More evidence of great cooking in Botswana may be found at the Sanitas Garden Centre near to Gaborone Dam. Seswaa, the classic dish of the Batswana, is often on the menu. It is a tasty dish, but hard work to make. Essentially a cow, pounded and smashed to smitherenes, it is slowly cooked to a dry and stringy result, with plenty of fragments of bone and attendant marrow. Alongside the pulverised bovine, one traditionally recieves a good helping of mealie pap (polenta), gravy, and a concoction of green vegetables called ‘morogo’. Spinach seems to be part of the mix, however I’m also told that various kalahari grown wild herbs are essential exotic requirements.

Another southern African classic from Sanitas, bobotie and rice. Minced beef, with a combination of fruit, curry and pepper typical of Karoo cooking, and topped with an egg mix. Again excellent.

A further recommendation: the patio of the Grand Palms Hotel, next to its lake, swimming pool, and play area, serves good home made burgers and salads.

Botswana then is a place for good food. Yes, there are many second or third rate restaurants springing up amongst the brash new shopping malls. And yes, Motswana are adicted to badly fried chicken. But if you know where to look, there are some world class gems.

September 30, 2007

My Family and Other Primates, Kruger Park 2007 Part 6

Follow-up to My Family and Other Primates, Kruger Park 2007 Part 5 from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

A Kruger bull in detail (click to enlarge)

Read the whole story…

1. The boy and his bushbuck, at Letaba

2. Monkeys, not such distant relations

3. Swinging through the trees, near Shingwedzi

4. Lions, a critical assessment

5. Drifting on the thermals, from Shingwedzi to Olifants

6. Elephants are big and grumpy, but fun to watch

Elephants are big and grumpy, but fun to watch

Mafunyane, Shawu, Kambaku, Ndlulamithi, Dzombo, Shingwedzi, Joao, Mandleve, Nhlangulene, Phelwana. We entered the great Elephant Hall in darkness. As I held the door open, Lawrence at my feet and eager to enter, bright sunlight projected shadows of the beasts onto the whitewashed walls within. Ordinarily they were simply massive. Now they had become utterly monstrous. I know the true life horror stories well, they make good tales to tell on long dark nights in the bush. Another of Kruger’s camps has a photo gallery to prove that they are not mere urban myths: cars crushed flat by 7000 kilos of angry Loxodonta Africana; surely no one escaped alive? Sometimes it happens, and no one blames the elephant: the tourist just can’t get the right angle for his camera, so he opens the door and steps out. But that gesture is, to an elephant bull in musth, an irresistable challenge. Hardly a fair contest. At Delta Camp in the Okavango we once felt happy to have been given a freshly constructed reed hut to sleep in. On the first night an elephant brushed past. In the morning they showed us photos of the previous construction, flattened by a tusker in search of fresh water.

When an elephant means business, it nearly always comes immediately and without warning except for a momentary rocking motion of its body; sometimes it comes without a sound. The tail stiffens, the tusks are held high and the trunk is drawn in against the chest. The ears are usually, but not always, spread out to their full extent giving the head a most awesome frontage of 12 feet or more. Bere, R. 1966, Wild Animals in an African National Park

Mafunyane, Shawu, Kambaku, Ndlulamithi, Dzombo, Shingwedzi, Joao, Mandleve, Nhlangulene, Phelwana. Tusks held high against dark shapes like vast threatening ears. In the darkness each of these great tuskers stood threateningly above us, as if still alive and gathered together for a conference of elephant bull ferocity. Ghosts of Kruger’s greatest, a power-cut having summoned them back from the dead. The receptionist in the Letaba Elephant Hall seemed entirely unconcerned. The lights would be back soon, she optimistically claimed. Lawrence does not yet like the dark, so we retreated, returning later to see the awesome collection of elephants, some of the biggest ever recorded. The museum made a lasting impression on Lawrence, we visited five times. He was particularly keen on a jar containing a pickled snake – very much like the Museum of Natural History in Oxford that he loves so much.

Giant elephants are, in the Kruger, not simply a matter of history. We have seen many, and have sat safely watching them for hours. The Kruger is one of the best places to see them. In northern Botswana, along the Chobe river front, it’s not unusual to find several hundred elephants together. From a boat that is spectacular, but when we got trapped amongst them in a bakkie, a rather more tense situation emerged. Add to that the overzealous safari operators, with Landrovers full of $1000 a night guests, then trouble is inevitable. In the Kruger the small family herds seem more relaxed, less harrassed. Whereas the Chobe/Linyanti/Zambezi area has around 100,000 elephants, the Kruger Park has 13,000. And so we can get close and intimate with elephants acting naturally…

(click on a photo to enlarge it)

Here are some photos of a small family herd. They ran fast across the road behind us as we were heading towards Olifants Camp, having climbed up a steep incline from a river bed. A vehicle in their pathway was shooed away like a fly. They then settled into play and grazing, allowing us to get some nice photos.

Does her bum look big in that?

Occasionally elephants are unpredictable. We had been trumpeted on a couple of occasions. Emma claims that I always get too close to the elephants. Lawrence learnt from her to say:

Daddy got too close to the elephant.

But in this case, it was Emma at the wheel of the car, although she could not have predicted that a male in musth would be following the small family herd that had just crossed the road. The big male gave us a trumpet, a bit of ear flapping, and a small mock charge.

Emma’s obvious alarm was actually caused by her inability to get the car into reverse. She had never put an automatic gearbox into reverse before. Not a good time to learn.

We also had a rare opportunity to see a herd of elephants in the rain, making for a very different photograph…

September 24, 2007

My Family and Other Primates, Kruger Park 2007 Part 5

Follow-up to My Family and Other Primates, Kruger Park 2007 part 4 from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

1. The boy and his bushbuck, at Letaba

2. Monkeys, not such distant relations

3. Swinging through the trees, near Shingwedzi

4. Lions, a critical assessment

5. Drifting on the thermals, from Shingwedzi to Olifants

6. Elephants are big and grumpy, but fun to watch

Drifting on the thermals, from Shingwedzi to Olifants

From Shingwedzi in the centre of the park a long hot strip of grey tar runs southwards. It was our route for over an hour, passing through varying degrees of mopane dominated landscapes, interrupted by the occasional dry river bed and cluster of larger riverine canopy.

Mopane gives the north of the park an unfair reputation. In places, that grow-anywhere arid-zone tree is tall and dense, standing as thick mopane woodland on each side of the road. When the poor soils are even thinner and sandier, on the sandveld, mopane is a mere shrub, still densely arranged but short enough for an antelope’s head to protrude through the canopy. Flying across the Kalahari, one sees this landscape in famously endless iteration. The northern Kruger is the southernmost extent of that harsh world. However sometimes, if the conditions are suitable, grassland is interspersed with mopane and other trees, forming a sparse density of vegetation. Such terrain, known as parkland, is more suited to cheetah visioned and lion obsessed tourists. And that is a problem for the Kruger Park Management, who would very much like to attract people away from their over concentration in the big southern camps (Satara, Skukuza etc).

As my pervious journal entries demonstrate, the park to the north is a wonderland rich in a diversity of birds, animals, trees and flowers. There was for us no end to this on our journey south. The trick is to zoom in and around the scenery. Become panoramic, and mopane is breathtaking – a near permanent display of autumn golds and reds. Then zoom back in to find birds and animals scattered around its vastness. At one water hole, near to the Mopane Camp, there is almost always a fascinating crowd gathered: various species of vulture.

Whiteheaded vulture (click to enlarge).

We broke the journey at Letaba, the temperature had climbed to 36 celsius. And then onwards. More mopane. On such long hot days, Olifants Camp is a relief – rising up into the cool breezes that circulate along the high rocky ridge upon which it is placed.

The Olifants River viewed from our patio.

The vast Lebombo Guest House was our eyrie (£125 a night, sleeps 8). From here we could watch eagles, vultures and storks drifting past as they caught the early morning thermals.

A saddlebilled stork passes by.

The Lebombo Guest House is in fact a sprawling complex of three buildings, one of which houses two bedrooms, a kitchen and large lounge, with the other two hosting two further bedrooms each.

The two large patio areas include a braii, upon which I cooked nyala steaks.

The comic rumbling of hippos sounded from far down the mountain side.

Along with water falls as the river cut through the varying strata of rock.

Meanwhile, Lawrence enjoyed his newly discovered sport, lizard chasing.

And went for an elephant ride…

On a morning game drive, Emma photographed a family of hyenas lying next to the road near their culvert den, in exactly the same position that they had been in last time we came to Olifants ten years ago. They do not look like they have moved, or have any intention to do so.

On our second evening, Emma and I had dinner in the restaurant: a superb buffet, with a great game stew not to be missed.

September 19, 2007

My Family and Other Primates, Kruger Park 2007 part 4

Follow-up to My Family and Other Primates, Kruger Park 2007 part 3 from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

1. The boy and his bushbuck, at Letaba

2. Monkeys, not such distant relations

3. Swinging through the trees, near Shingwedzi

4. Lions, a critical assessment

5. Drifting on the thermals, from Shingwedzi to Olifants

6. Elephants are big and grumpy, but fun to watch

While staring at an unusual object it cannot identify, an impala will move its head up and down and sideways, apparently to see it more “in the round”. Estes, The Behaviour Guide to African Mammals, 1991, p.166

Estes provided, as ever, a reliable description of the African tableau before our eyes. For some time, animals moved backwards and forwards along an area of open space above a small vlei, half an hour’s drive to the north of Oliphants Camp in the Kruger National Park. A string of zebras, wandered through small groupings of impalas, an animal accurately described by Estes as “the perfect antelope”. An occasional wildebeest mingled and munched upon the sparse but adequate vegetation. Nothing unusual. Just another day on the way to the waterhole.

Assorted zebras and impalas – click to enlarge

Observing closely the black scent glands on the hind legs of a large buck impala, I was reminded of a closer encounter from a few years earlier. It was then, on the day of our wedding in Hwange National Park, that we had an opportunity to observe this typical mopane-veld resident at very close range indeed. The hosts at the venue for the happy day, Jijima Camp, had “adopted” an impala – or perhaps more accurately, had been adopted by one. The animal slept next to our tent, as it would every night, ruminating in relative safety. Although leopards and lions are occasional visitors to such un-fenced camps, the impala was probably correct in assuming that close association with humans would offer a greater degree of security from survival of the fittest. And this then is how my copy of Estes obtained its unusual signature. Buck, as the impala was known, stood just a couple of metres from the front of our tent. A male impala, complete with horns, is at close range quite an impressive sight. However, all of its dignity is immediately lost when it starts to bob and weave its head in the quizical manner described above. Buck was obviously confused by some aspect of the scene that I presented. My inevitable laughter only made him more agitated. In an effort to diffuse the situation, I sought to restore the natural order by reading aloud to him the prescription of ideal impala behaviour given by Estes in the very book that I was at that point casually flicking through. I then gave Buck the opportunity to confirm or deny the stereotype of his kind presented by the finest of zoological minds. And what was Buck’s response? In a flash he lept forwards, and with his powerful jaws ripped the book out of my hands, tossing it high into the air. I dived out of the way to avoid being impaled by his horns. And so pages 137 to 156 of my copy of the Behaviour Guide to African Mammals are now indelibly imprinted with the teeth marks of an impala, that most perfect of antelopes.

The memory of Buck amused me for long enough to be surprised upon the return of my attention to the current scene. Some unidentifiable tension had stirred during my reverie. The behaviour was again that of a quizzical impala buck: upright stance, twitching ears and tail, moments of concentration interspersed with that comical bobbing and weaving. He was, as Estes says, trying to see something more “in the round”. And we knew exactly the cause of this sudden alertness. Just after setting off from Oliphants, the driver of the early morning game drive had tipped us off. Lions had been spotted, he said, giving a quick and simple description of their location. We thought that Lawrence might like to see them, not having done so before. Otherwise, we may not have bothered. And here they were, as described, two females lying beneath a small tree. For some time potential prey had passed by seemingly unaware of the deadly duo within easy ambush range. Until finally contact was made between killer lion and lion food.

The stand-off – click to enlarge

How terribly dramatic. Imagine the Jonathan Scott commentary, suggestively hushed. Imagine the camera crew poised to get the kill in the can. Imagine the millions of viewers earnestly believing that this is real Africa.

Oh dear, and now I have to spoil the illusion. For reality is rarely like the movies, especially when a lion is in a leading role. To continue the Hollywood analogy, the truth is that they are more like Brando than Brosnan. Big fat and lazy. With huge potential and a very occasional blockbuster, but more suited to lying flat out next to the pool for days on end sipping Martinis. This impala knew the score, and was entirely unworried. Even his brief expression of interest waned quickly. Hundreds of other prey animals in the area didn’t even bother to look, although they must have known that the lions were there. Lawrence agreed. The lions were of no interest. “Where’s the monkeys?”. After the event, we have to remind him that he has seen lions, because the reality is nothing in comparison with the Lion King.

Unimpressive lions – click to enlarge, if you really want to

While ambling slowly back to the camp, Emma and I recalled our many encounters with lions, from our many many safaris. We both sense that we have seen many lions, although the sightings tend to blur into one vague impression. Sightings of cheetah, leopard and even wild cat always stand out, partly due to their rarity, but more as a result of the stunning presence of those lesser cats. There was a particularly notable male lion that I tracked along a road in the Kalahari Gemsbok Park. He had a black mane, and seemed massive, with the top of his head reaching above the window of our Hilux (a really tall 4×4). Emma wound her window up with unnecessary haiste. And then there were the lions that visited our lonely camp at Nqwethla, deep inside Hwange. We had already been driven out of our tent by an elephant. I had spent part of the night pouring parafin onto an open fire so as to scare the pachyderms off with a fireworks show. The flames seemed to at least distract the elephant from the task of trashing our camp. But they had no effect upon the noisy family of lions that walked by as we hid.

So you want to go to Africa? You deperately want to see lions? Our long standing family joke is this: one year in Hwange, a party of very annoying Americans spent their time racing around the bush, repeating the same question with urgency – “have you seen any cats?” (said with annoying American accent). Of course they missed the wild dogs, bee-eaters, and troop of banded mongeese.

Do you still want to see lions being interesting, just like on the TV? There is one last possibility. We tried it a few years ago. It works like this: Go out walking with a really good game ranger. We were lucky to walk with the legendary Frank Watts at Shimuwini Camp in the Kruger. When you spot many lion tracks, just believe him when he says that it’s perfectly safe (assume that he means that they are long gone). Then follow him up a hill, heading towards the most foul smell of death imaginable. At the top of the hill, examine closely the big runny black slick of lion crap. Proceed further, nominating a charmingly innocent member of the party to take the lead. Emma was rather surprised when a big lioness ran across her path. As we approached the half eaten carcass of a buffalo, we could hear the rest of the pride running in all directions. Yes, we had driven a pride of lions of its kill. Cowards. Frank examined the carcass for signs of bovine TB, a serious issue in the Kruger. It looked healthy. With the light fading, we slowly wandered back to the Landcruiser. Being at the back of the line, I was last to get into the safety of the vehicle. While waiting for my turn, I sensed movement behind me. I turned as I climbed into the open back of the vehicle. A fully grown male lion, complete with impressive mane, stood staring assertively at us. I could read his mind: “don’t mess with my dinner – or next time you’re dessert.”

Recently, Frank hit the headlines as the safari guide in the world famous “battle of the kruger” incident, the video of which is on YouTube. Amazingly, a herd of buffaloes fought back against a pride of lions that had taken one of their young. The buffalo survived. The lions almost didn’t. It may even be the case that this is the same cowardly pride that we encountered several years earlier.

Importantly though, I must say that the best drive that we’ve been on with Frank typified the ideal game drive. On a sunset trip there were no lions, but rather a sequence of fascinating insects and birds, including a nightjar and a sun spider.

You can find out more about Frank’s work on the Thompsons Indaba Safari Company web site.

August 29, 2007

My Family and Other Primates, Kruger Park 2007 part 3

Follow-up to My Family and Other Primates, Kruger Park 2007 part 2 from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

1. The boy and his bushbuck, at Letaba

2. Monkeys, not such distant relations

3. Swinging through the trees, near Shingwedzi

4. Lions, a critical assessment

5. Drifting on the thermals, from Shingwedzi to Olifants

6. Elephants are big and grumpy, but fun to watch

3. Swinging through the trees, near Shingwedzi

The Kanniedood Dam captures a short but significant portion of the otherwise desertified Shingwedzi River as it passes through the Kruger National Park, just a small distance from Shingwedzi Camp. Kanniedood is from the Afrikaans for “cannot kill”. Even now, in the middle of the long harsh dry season, it lives. For a few kilometres, the waters are wide, deep, cool and uninterrupted. Further away from the camp, it almost looks to be in flood, as the rough game viewing track through the riverine forest runs close down to the waterline. There are many crocodiles, some with jaws wide open and inviting small boys to clamber in and explore (in the manner described by several popular story books).

The deceptively weighty hippopotamus also abounds. On a hot day like this their water-bound lounging only confirms the stereotype, but later as it cools they will come onto dry land and show off their improbable speed (we once drove alongside a hippo at night – the speedometer was reading 30 kmph).

Deep inside the Kruger National Park the density of large wild mammals is quite epic. It is one of the few places left where humans are not in charge.

Elephants: giant solitary males, boneheaded and tusk laden, just hanging around at the waterholes; matriarchal breeding herds, with tiny infants scurrying alongside in the procession to or from water and food.

Giraffes, just as described by Giles Andreae

Gerald was a tall giraffe, whose neck was long and slim, but his knees were awfully bandy and his legs were rather thin.

Burchell’s zebra with a pink sand-stained tinge to their designer stylish black and white stripes, contrasting artistically with their constant companions, the goatee bearded blue wildebeest (in this strong light they really are blue).

Antelopes in three flavours: slender brown impalas, females gathered into hareems jealously guarded by a tall-horned male busily marking out his territory with the large black scent glands on his back legs; dark-grey waterbuck, with great horns curving upwards to match their white round posterior markings; and the disneyesque nyalas, females mid-brown and painted with precisely arranged spots, but also blackened males, with tall spiral horns and stripes, so dissimilar to the females as to appear to be an entirely distinct species.

And if any of these beasts were to feel itchy, perhaps with a tick buried deep in the fur, the many attendant ox-pecker birds are very happy to assist. We saw one impala carrying six of these medium sized brown birds, red and yellow bills probing for parasites. For a certain type of human, the Mashongeni bird hide, looking out across the Kanniedood Dam, is a place to feel “twitchy” – a condition easily relieved by the many different species to be seen: storks, bitterns, egrets, herons, kingfishers, swallows, swifts and martins, each in several varieties. England has just one kingfisher. Here in the Kruger it’s not unusual to see four or even five of the ten different South African species in close proximity. And there are raptors, again multifarious in type and habit. Across the dam the fish eagle is dominant, perching in the tall trees that line the banks. We found one particularly impressive individual high in the lime-green branches of a fever tree. Occasionally it swooped out across the water, whistling four loud and clear notes in a descending scale.

All of this was of interest to little Lawrence (two years old). Between sightings he battled for control of the truck’s electric windows, or struggled to break free of his baby seat. But given something impressive to look at, he would concentrate and focus, enjoying squirrels as much as buffaloes and lions.

Fortunately, Lawrence has not yet seen many wildlife documentaries about Africa. People who come out to the Kruger Park expecting lions making a kill every ten minutes are always bitterly disappointed. Hoping for lions to do anything other than just lying still in the shade of a tree is entirely unrealistic. Small children have the advantage of being without such preconceptions. And so we were able to spend time, on several occasions, watching closely the most fascinating animal behaviours. Forget lions and leopards, people spend far too much time thrashing around in search of those thoroughly dull creatures. Lawrence will tell you the name of the best animal in Africa…

“Bobo”.

In the language of a two year old, that means primates: in the Kruger Park, vervet monkeys and chacma baboons, often in large packs, and always boisterous, busy, social, playful and clever. Jez Alborough is responsible for their generic reclassification as “bobos”. His classic picture book Hug tells the story of the baby chimp Bobo lost and alone in the bush. Lawrence has drawn a strong and persistent connection between this story and the monkeys and baboons that he sees in the bush. He does know that they are different. He understands the separate species, but there is something in what he has seen that connects fiction to reality. I think the connection is significant. The book has few words, but communicates a strong narrative. The illustrations are left to do all of the work. The facial expressions and bodily gestures of the chimp are easily understood. They do a great job in helping a young child to understand and identify emotions. One may argue that it is just anthropomorphic nonsense. But I think that Lawrence would disagree. The primates that he has seen, especially the big social groups, are full of expression and meaning. Spend just a little time watching them and you will see gestures and behaviours that express relationships, values and shifting moods (what in humans we see as emotions). Youngsters and lower order adults groom the alpha female. Children play and learn. Young male adults wander off to explore and then run back to the group.

“Bobo, what are you doing in that tree?”

“Where’s your mummy Bobo?”

“Bobo swinging through the trees.”

And most hilarious of all:

“Bobo’s got a sore bottom” – on seeing the engorged red posterior of a female baboon.

Every second was full of action. Running and gymnastically flying between branches at a similar frenetic pace to a human two year old, the display was both spectacular and hilarious. The little primatologist in the car alternated between shrieks of laughter and silent fascination, learning throughout.

Forget big cats. Monkeys (or bobos) are best.

August 23, 2007

My Family and Other Primates, Kruger Park 2007 part 2

Follow-up to My Family and Other Primates, Kruger Park 2007 part 1 from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

1. The boy and his bushbuck, at Letaba

2. Monkeys, not such distant relations

3. Swinging through the trees, near Shingwedzi

4. Lions, a critical assessment

5. Drifting on the thermals, from Shingwedzi to Olifants

6. Elephants are big and grumpy, but fun to watch

Not such distant relations

The little monkey boy lolloped towards the two indignant females, his intent obvious to all but himself. A poorly acted hunchbacked stoop hid his otherwise youthful athleticism, perhaps a tactic to put them at their ease. One day in the future he will be the alpha male of the troop, but for now he is just another buffoon.

He scampered, arms swinging loosely, knuckles almost dragging across the ground as if his species had only recently descended from the tree-tops to explore and exploit savannah Africa. A glint of drool dribbled from the corner of his chattering mouth, sharp white teeth on full display, an ape with a gape. Primitive. And then, with his face close to that of the smaller of the girls, he began his flamboyant mating dance.

In her doctoral thesis, the primatologist Dr Jane Goodall described just such behaviours amongst the chimpanzees of the central African rainforests. Here, in the Kruger National Park of South Africa, the little monkeys were dancing to a similar over excited tune. We watched from a distance, awed by this snapshot of our own simian ancestories. So closely related, as DNA proves, and yet so far.

His two feet repeatedly left the ground almost at the same time, bouncing a short distance into the air, right foot slightly ahead of the left with the syncopation of a jazz band. Landing with a dusty thump, he kicked up a fine cloud of sand towards the young ladies, at last forcing them to acknowledge his presence. Arms outstretched like some great bird struggling for flight, he flapped and bounded on the spot, grunting and blowing. They were, in response, deathly unimpressed.

The young male continued. Throughout the performance, his balance precarious. The older of the females tempered her disdain for the precocious ape with fascination, albeit with nothing other than the improbable physics of his art. Sensing failure, the young male only became more frantic in his attempts to make the girls notice. This impetuosity led to his downfall, when his left foot found an unexpected obstacle: his right foot seemed to have its own rhythms and reasonings. He paused for a second down on his posterior, and then sprang to his feet whilst shooting out both arms as if to say: that was all part of the act, i'm so good I even fall over with style. The older female passed him a sideways glance, and then continued with her own more interesting occupation, examining the jaw bone of a long dead elephant.

Making no progress with the girls, the monkey boy temporarily broke away in order to pick a small stick off the ground. The stick was alas imperfect. There followed a few seconds of motionless consideration, the inner machinations of his brain made visible on his face. We were reminded of George W. Bush 'deep' in thought. A metaphorical lightbulb flashed above his head. Quickly he stripped away the surplus twigs and leaves, creating the perfect stick with which to scrape the bare earth at the feet of the females. Eureka, the primate makes a tool.

He is evolving. But not quickly enough it seems. The females escaped with haste, speeding up a gnarly old tree. The older girl quickly climbed to a couple of metres, her small feet delicately wrapping around its painfully rough bark. The smaller of the two found herself a more gentle route of escape, clambering along a fallen log. Too fast and agile for their persuer.

Finally, the young male was visibly disappointed, staring up at the older female he vocalised his confusion. As experienced monkey watchers, we could easily decipher his primitive chattering:

"Where's your shoes?"

The little monkey boy speaks! But the young females do not quite understand. They are of the Southern African sub-species. He is a member of the superficially similar but actually very different Homo Sapiens Warwicensis, originating in central England, but having been released into the Southern African biome by misguided tourists (it has since caused great damage to the environment in and around the Kruger Park, incessantly raiding kitchens for scraps).

In the field, young females of the Southern Africa sub-species of the Homo Sapien ape can be identified by three distinctive traits: greater than expected physical strength, an ability to climb any surface barefoot (as observed above), and girly pink clothes with a light dusting of sand.

From the safety of her perch, high up in the tree, the older female (Jessica, aged 6) turned towards the observing zoologists and spoke:

"He's a bit of a funny bunny."

"Yes," I replied, "but he is only two years old. His name is Lawrence."

"My sister Rebecca is four."

"Lawrence is on holiday, he is from England."

With Jessica taking the lead, the girls finally became interested in Lawrence. He was, after all, only two years old and English. It was then perfectly fine for him to be a bit of a funny bunny. For the following thirty minutes they explored the trees, the elephant jaw bone, and the various items of furniture and decoration around the restaurant at Shingwedzi Camp. The girls outclimbed and outclambered him. When he fell they picked him up. When he got nervous they comforted him and encouraged him on. After half an hour they were all equally dusty, but very happy.

Three little monkeys playing in the dirt of the Kruger National Park, South Africa.

Lawrence entertaining the ladies at Shingwedzi Camp restaurant

Funky monkey

August 22, 2007

My Family and Other Primates, Kruger Park 2007 part 1

1. The boy and his bushbuck, at Letaba

2. Monkeys, not such distant relations

3. Swinging through the trees, near Shingwedzi

4. Lions, a critical assessment

5. Drifting on the thermals, from Shingwedzi to Olifants

6. Elephants are big and grumpy, but fun to watch

The boy and his bushbuck, at Letaba

Just as I had expected, he was immediately at home in this sandy hot place. A small boy excitedly feeding fresh green leaves to a female bushbuck antelope on a desiccated African lawn. The bushbuck is taller than the boy, and adapted to a life as potential leopard food. It is a wild animal, but that doesn't stop Lawrence from claiming it as "my bushbuck".

The strip of cultivated garden in which they play runs down towards the wide sandy bed of the Letaba River, stretching about one kilometre across to a distant bank lined with riverine trees. Beyond that, there is mopane covered sandveld all of the way to Moçambique and beyond. The river is in its dry-season state, empty apart from a narrow distinct channel lined with reeds and waterbirds, alive with crocodiles and hippopotami. Holding the twig with an evident sense of amazement, the little boy shrieks like a monkey as a long thin grey antelope tongue shoots out to grasp and strip the leaves in a curling grip.

Elephant in the Letaba River

We travelled more than 24 hours for this, the end result being ample opportunity for (almost) 2 year old Lawrence to interact with the wildlife of the African bush: feeding them (bushbucks), chasing them (guinea fowls), laughing at them (monkeys and baboons), imitating (hadeda ibis, "ha-dee-da, ha ha, ha-dee-da", and the giant ground hornbill, "hoo-hoo-hoodoo"), and watching intently (elephants, giraffes, hyenas, warthogs, lions etc).

Chasing guinea fowl

Hadeda ibis

Ground hornbill

Sceptics in drizzly sad England had expressed their can't-do misgivings: a 2 year old obviously being underage for such adventures - too far, too hot, too cold, too wild. And besides, he would never really understand and appreciate it. However Lawrence is a little different to the average English kid, having grown up in a house full of African wildlife photography, he knew jackals and vultures before the English fox and red kite. Although his impersonation of the call of the African fish eagle has long been hampered by his inability to whistle, it doesn't deter him from trying to make that archetypal wild African sound. Upon seeing and hearing that wonderful bird swooping across the vlei, his imitation of its call (a series of soaring whistles that seem to embody its graceful flight in sound) was recognisable. And he has been to Africa before, as a small baby, so is perhaps at least to some extent acclimatised to it.

The journey had indeed been long, although mostly tolerable. At 12.30pm on Saturday grandad Dermot turned his limousine south towards Heathrow. Let's just forget the hell that is Heathrow. Lawrence slept on the 747 to Johannesburg (cost about £2000 for two adults and a child). At 12.30pm the following day our tiny South African Airlink plane landed at Phalaborwa on the edge of the Kruger Park (flight cost around £60 one way for two adults and a child, including a dramatic view of Blyde River Canyon). In the tiny safari styled airport, African grandad "Growwer" and grandma "Googoo" met us, having driven across from Botswana, their sudden appearance surprised Lawrence, even though it was promised for some time. At Phalaborwa we collected a comfortable and capable Honda CRV 4x4 from the National Alamo office (about £25 a day), and drove the short distance to the park entrance. From there on to Letaba Camp 100km into the park, with Lawrence snoring happily past buffaloes and elephants.

Emma and I know Letaba well, and chose it to be Lawrence's first home in the African wilds. The ingredients that make it ideal include:

- Green shady spaces in which to play, with plenty of interesting features such as bushbuck droppings and odd shaped seed pods;

- A café and a restaurant serving scrambled eggs and toast;

- An elephant museum with skeletons and models (Lawrence likes museums, especially with old bones and snakes pickled in jars);

- Big dangerous animals close by on the wild side of the fence;

- Smaller and safer wild animals within reach on what is, officially, the wrong side of the fence for them (somehow the bushbuck have invaded, and since our first visit in 1998, multiplied prodigiously).

And at the end of a frantic day chasing animals, we could eat and sleep comfortably in one of the thatched cottages provided for self-catering accommodation. In the past we have stayed in the small basic rondavels (£25 per night), but with some members of our party being habituated to a more sophisticated environment, on this occasion we chose the large Melville Guest House (cost £125 a night, sleeps 9). The house has a well equipped kitchen inside, and a barbecue in its private garden overlooking the river. Housekeeping was more than adequately supplied by Agostino from Maputo, guardian of the Melville.

The Melville was our home for just two nights. It is excellent, and we would have stayed longer if it were available. In that time we had two good dinners (thanks to Googoo and Growwer), interesting game drives in the park (particularly nice zebras, wildebeests and giraffes), and much time spent pointing and screaming at the giant skeletons and tusks on display in the museum.

Just outside the museum there is a much less deceased wonder. A small garden of aloes is planted around a full sized model of a big tusker. The flame-red and orange and yellow flowers of the various aloes top their succulent green stems, in vivid competition with a swarm of birds: tiny iridescent sun birds in green, purple and scarlet like over-weight hummingbirds; the black headed oriole with its strong yellow plumage; the grey lourie (known as the "go-away" bird, following its call); both glossy and red winged starlings; crested barbets in red, black, yellow and green; mouse-birds with feathery plumes; a red capped cardinal woodpecker tapping the bark for grubs; and at night scops owl calling with its repetitive "brurrr" - most unlike an owl. Their colouring is almost un-natural, the product of an aesthetic arms-race within each species, and maybe also against the drab sandy uniformity of the background landscape. Splashes of colour marked by an emphatic evolutionary brush in the surrealist style of Joan Míro, or the hands of a child artist. A light show matched with sound, irrational and off-beat, but beautiful, like jazz.

Black-eyed bulbul

Black headed oriole

Mousebird

Masked weaver

Glossy starling

Red winged starling

Red chested sunbird

The boy added to all of this in his own exuberant way.

Lawrence's first wild elephant

Robert O'Toole

Robert O'Toole

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading