All 39 entries tagged Coin Of The Month

No other Warwick Blogs use the tag Coin Of The Month on entries | View entries tagged Coin Of The Month at Technorati | There are no images tagged Coin Of The Month on this blog

July 01, 2016

The agreement of the armies under Nerva

|

Aureus of Nerva

Date: 96 AD

Obverse: IMP NERVA CAES AUG PM TR P COS II PP (Emperor Nerva Caesar Augustus, Pontifex Maximus, Holding Tribunician power, Consul twice, Pater Patriae.)

Reverse: CONCORDIA EXERCITUUM (Agreement of the Armies), Two clasped right hands holding an Aquila set on the prow of a ship.

This particular coin is not visually exceptional since the image of clasped hands recurs on many different coin types. What makes it of interest is the message it carried, and the role this played in Nerva’s attempt to stabilise his position as Domitian’s successor. In order to understand the coin’s significance fully, we must first consider the context in which it was issued.

Nerva became emperor in September of AD 96, the year in which this coin was minted. As such, this would be among the first coins to be issued under his rule. His predecessor, Domitian, had been murdered in the Imperial palace and condemned as a tyrant by the Senate. Looking at the relative stability of Nerva’s rule as emperor, especially when compared to the civil war and instability which followed the death of Nero – the last Emperor to be violently overthrown – it can be easy to forget the dangers that the new Emperor would have faced. The reluctance of the army to shift their loyalties to an unknown Emperor is likely to have been significant in the wake of Domitian’s murder. Domitian had been a generous military leader and his succession by Nerva, who had little experience or prestige in military affairs, risked a crisis like that of the Year of the Four Emperors.

It seems that fortune was in Nerva’s favour, however, as the military situation at that time meant that a military coup was not an option. The all-important Northern armies were engaged in an ongoing war along the frontier; to return to Rome to contest Nerva would mean turning their backs to the enemy and leaving the Empire vulnerable. At the time of his accession Nerva was also already 65 years of age –perhaps they thought he wouldn’t last long enough to be worth overthrowing.

With this in mind, the Concordia Exercituum coin seems perplexing. The legend translates to “Agreement of the armies” referring to unity of armies both with each other – as signified by the military standard, ship’s prow and aquila – and the Emperor. This might seem like a strange choice of message to send at this time to military and non-military inhabitants of the empire. The majority of Romans may have been ignorant of military politics. If this celebration of army unity were aimed at them, wouldn’t it have been like announcing the existence of a previously unknown problem? It would be similar to the captain of a seemingly steady aeroplane announcing ‘There is absolutely no cause for alarm’, a statement that would only invoke suspicion and paranoia. Similarly if the Emperor felt the need to reassure citizens of the army’s loyalty, then that loyalty must be in doubt. As for the military, Nerva was no doubt aware that they would feel anything but unity with a Rome that had murdered their leader and denounced him as a tyrant. To them, receiving such a coin in their salary would surely have been laughable at best, and a grave insult at worse, as Nerva proudly announces that they are loyal to him. As a gold coin, if this type were used in military pay, it would have come into the hands of wealthier officers and individuals.

Considering the events of summer AD 97, it can be argued that Nerva (or his advisors) had taken the wrong strategy with these coins. The Praetorian Prefect, Casperius Aelianus, led the Praetorian Guard to the Imperial Palace to demand the execution of Domitian’s murderers: the freedman Parthenius and Petronius Secundus (Aelianus’ predecessor as Praetorian prefect). Petronius offered his neck to the guards, saying that he would rather die than give into their demands, and was killed immediately. Parthenius was subjected to a much more gruesome fate. He was castrated, likely a deliberate snub to Nerva who had made castration illegal, then strangled to death. The incident deeply embarrassed Nerva, as the military’s disloyalty was demonstrated publicly. It showed his failure to pacify his own army and forced him to name Trajan as his successor. Trajan was a military man, chosen in order to appease the soldiers.

But it is worth considering Nerva’s perspective further before condemning him. He had, after all, already been involved in politics during the civil wars of AD 69, and thus had personal experience in dealing with civil unrest in the aftermath of an emperor’s overthrow. He would have witnessed the events that led to Galba being murdered at the hands of the Praetorian Guard in the centre of the forum. Surely Nerva would have known the care needed to ensure the loyalty of the Roman troops. Nerva appears to have modelled most of his coinage, besides the Concordia Exercituum type, on that of Galba. It makes no sense for him to have designed a new coin, which seemed only to insult the military whose allegiance it was so essential for him to win.

Perhaps we are reading the coin wrong. It has been suggested that one key reason that the troops were hostile to Galba was that he gave no donative to the army. Syme argued that Nerva would remember the danger of forgoing the donative, and would have provided one. If the Concordia Exercituum coin was issued alongside this donative (or formed part of it), then rather than being seen as an arrogant declaration of something that was not true, the type would instead have borne a message of hope: that this gift would inspire concord between Emperor and army. If viewed by someone in Rome, the message may have been read differently. Inhabitants of Rome were surrounded by monuments celebrating Domitian’s military career, and may have viewed Nerva’s proclamation against Domitian’s established military record.

Finally, we should not see the ‘conspiracy’ of Casperius Aelianus as a complete failure on the part of Nerva. The Praetorians under his command only demanded the execution of two men, the murderers of the previous emperor, a demand that Grainger calls ‘surprisingly moderate’. When compared to other successors of overthrown emperors, such as Pertinax and Galba (both of whom were killed by the Praetorian Guard) Aelianus’ conspiracy appears more to be evidence of Nerva’s success, than failure.

|

This month's coin was chosen and written by Nigel Heathcote. Nigel is a first year MPhil/PhD student in the Department of Classics and Ancient History at Warwick. His PhD is a study of the effects of being condemned as a tyrant upon the ‘physical legacy’ of an emperor in the city of Rome, looking at themes of destruction, appropriation and contrast. His academic interests focus on the propagation of imperial ideas through material culture.

Further Reading:

Secondary Sources

Bennett, Julian (2001) Trajan: optimus princeps (Indiana University Press)

Grainger, J.D. (2003) Nerva and the Roman succession crisis of AD 96-99 (Routledge)

Jones, B.W. (1992/3) The Emperor Domitian (Routledge).

Mattingly, H. & Sydenham ,E.A. (1926) The Roman imperial coinage. Vol.2, Vespasian to Hadrian (London)

Mattingly,H. (1936) Coins of The Roman Empire in the British Museum. Vol.3, Nerva to Hadrian (London)

Syme, R. (1930) ‘The Imperial Finances under Domitian, Nerva and Trajan’, JRS 20: pp.55-70

Primary Sources

Cassius Dio, Roman History, trans. Cary, E. (Harvard University Press, 1914)

Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, trans. A. Thomson (Philadelphia: Gebbie & Co. 1889.)

Coin image reproduced courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.

June 01, 2016

"Coins against Humanity"?

|

'Spintria' found in the Thames in 2012. PAS LON-E98F21 |

An Ancient Roman may not have been able to bring “Cards Against Humanity” to a pub game night, but they were able to bring spintriae. This particular sexy spintria was made famous when it was discovered in the Thames in 2012. There are several theories about the function of spintriae. People have suggested that they could be brothel tokens. Maybe the original owner of this token picked it up at the games? Or is it, as the title suggests, a game piece? One thing is for sure, the obverse is something that the user would remember and maybe even laugh at.

Two out of three theories are wrong. Suetonius wrote that Tiberius outlawed the use of coins stamped with the imperial image in bordellos (Clarke 1998: 244-245). This has led scholars to believe that these were brothel tokens. The idea that brothel customers would use these to pay for the services they wanted has been quickly dismissed (to see a more detailed discussion of this see Clare Rowan’s blog on this spintria).

This leads to the second theory. These tokens would be given to the public at public games. The idea this comes from a passage in Martial: “Now come sportive tokens (lasciva nomismata) in sudden showers.” (Martial Epigrams 8.78) These “sportive tokens” may be spintriae. That may seem like an odd token to give to spectators at public games celebrating things like military triumphs, but when considering the tensions in a society that placed importance on the lusts of men and the chastity of married women then maybe men receiving tokens to spend at a brothel might not be so bad (Knapp 2013: 236). However, this is not the case. The tokens would then be redeemed for gifts, but not at the local brothel. They could also provide a bit of a tough spot for an emperor who did not have the best press coverage. For example, viewers could be reminded of Tiberius’ sexual acts with boys on Capri (Suetonius Life of Tiberius 43-44). It is unlikely that an emperor, would want his people to snigger behind his back for what he got up to in his private life; thus, this theory seem implausible.

This leaves us with the third theory: these are game pieces. Although we don’t know what game these pieces were used with, we can be pretty sure that it was plenty of inspiration for the scenes of the game makers. There are other spintriae that have numbers going from I to XVI (1-16), but the sex scenes are different. This has led some scholars to believe that there is a correlation between the numbered spintriae and the illustrations of the sex manuals (Clarke 1998: 244, Clarke 2007: 194-5). This is also similar to the Pompeiian wall paintings found in the Suburban Baths. These are believed to have been numbered in a way similar to the lockers in the men’s changing room. As an added memory device, a taboo sex scene was placed above the number. The person using that space may not be able to remember his number, but they would probably be able to remember that funny dirty picture above it! (Savenga 2009).

This humour and function as a mnemonic device carried over to the game containing the spintriae. This spintria is tame compared to some of the other spintriae, so it was probably not one that was laughed too much. The steamy scene between this man and woman would have made the game memorable and may have reminded the player of what he had seen, read, heard, or even done. The fact that spintriae have been found in a widespread area, indicates that it Ancient Romans tended to have similar humour, played similar games, or that people loved this game so much that they brought it with them when travelling. Unfortunately, it may have been a male-only game. There were complaints [in Ancient Rome] that naughty pictures were corrupting respectable girls (Langlands 2006: 53). So, while the same sense of humour as a game of “Cards Against Humanity”, it might not have been a game to bring along to a game night with mixed company. However, it is not unreasonable to think that some clever minxes did manage to play “Coins Against Humanity”.

This month's blog was written by Katrina Anderson. Katrina is a Master’s student at Warwick University, who has recently become interested in the role of sex and gender in Ancient Roman art.

Bibliography

Clarke, J. (2007) Looking At Laughter. (London: University of California Press).

Clarke, J. (1998) Looking At Lovemaking. (London: University of California Press).

C. Rowan, Coins at Warwick: Ain’t talkin’ ‘bout love. Roman “Spintriae” in context.(1 Aug 2015). Accessed 10th May 2016.

Knapp, R. (2011) Invisible Romans. (London: Profile Books).

Langlands, R. (2006) Sexual Morality in Ancient Rome. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Martial, Epigrams, trans. Shackleton Bailey, D.R. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press: 1993) 2 vols. from Loeb Classical Library.

Sayenga, K. Sex in the Ancient World: Prostitution in Pompeii, Documentary, directed by Kury Sayenga (2009; New York: History).

Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, trans. J.C. Rolfe (London: William Heinemann: 1913) 1 vol. from Loeb Classical Library.

April 01, 2016

Crocodilian influences on the denarius of 28 BC

|

| Denarius of Augustus from 28 BC. |

The first recorded time a crocodile appeared on a Roman coin was 37/36 BC, under the authority of M Licinius Crassus, an official who had authority over the Greek island Crete and the African region of Cyrenaica. Scholars have attempted to claim that this was the son of the triumvir Crassus who in 53 BC famously conducted the Parthian disaster. The historical content of the Crassus coinage is dubious and complicated but it would be fair to assume and accept scholarly debate that his crocodile represented renewed Egyptian authority over Cyrenaica, an honour that was ceded to the Ptolemaic ruler Cleopatra VII by the cunning Marc Antony.

However, when Augustus utilised the crocodile on his coinage it was as a focal point of celebration towards Rome’s acquisition of Egypt and revered his military triumph. The crocodile interestingly could serve as a sign of continued power and dynastical tenure or the polar opposite of capitulation. With the caption of ‘Aegypto capta’; ‘captured Egypt’ we are able to understand the multi-faceted potential of a crocodilian representation and how the crocodile signified power dependant on the way it was utilised .

To understand the sole purpose of the crocodile on the denarius of 28 BC would be enormously difficult. Commonly in Egyptian practice, crocodiles were to supposed to allude to, and be associated with, their relationship to the river god Nilus, from whom Egypt’s affluence and prosperity was supposedly derived. The crocodile was the epitome of Egyptian power and was typically indigenous to the Nile so it often acted like a glorified mascot. Augustus had left his use of the crocodile imagery purposefully open to interpretation so that it could represent the formidable animal in which the Romans were so curious about, and were so proud to have enslaved, because it embodied the fate of Egypt. Or did it signify and celebrate the prosperity of Egypt through the crocodile’s relation to Nilus?

The best insight into the truth is the coinage of the colony of Nemausus (Nîmes) struck under Augustus: here a crocodile is depicted chained to a palm tree and is undeniably the sign of Egypt subdued to the power of Rome and presumably is a continuation of attitude from the denarius of 28 BC. The obverse of the denarius of 28 BC, a bareheaded and heroically unadorned bust of Augustus, has a protuberant brow alongside a wry smile which is meant to reaffirm the legitimacy of his autocratic reign by reasserting his military success, ultimately bringing us back to the subject of power. The crocodilian imagery on these coins was a boast of power, eastern luxury, but more importantly, it was who wielded and subjugated the crocodile that decided who the ancient beast would transfer its power to.

This month's coin was written by Alfred Wrigley. Alfie is a second year ancient history and classical archealogy student who is hoping to specialise in and write his dissertation on Julio Claudian coinage.

This month's coin was written by Alfred Wrigley. Alfie is a second year ancient history and classical archealogy student who is hoping to specialise in and write his dissertation on Julio Claudian coinage.

Coin image reproducted courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.

March 01, 2016

The Proculus Enigma: Have the history books been telling it wrong?

|

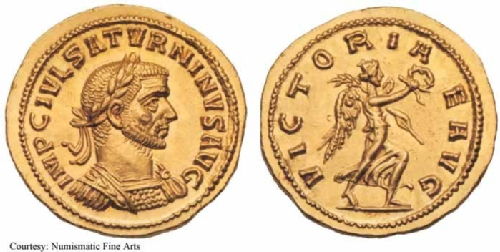

| Figure 1: Proculus Billon ‘Radiate’ (2.96g, 19.27mm) |

Before discussing this particular coin of the month, please forgive the Herodotus-esque digression on the context of its appearance. The day was November 7th 2012, and it began much like every other for one Yorkshire metal detectorist. The site he had chosen for the day had produced numerous finds in prior visits, most of which had suggested that he was walking in the footsteps of his Romano-British forebears. At this point, a thought may even have crossed his mind that his next find might be something other than Roman ‘grot’(derogatory archaeological slang for a heavily corroded and illegible Roman (typically) coin). Yet one object was, and all it took was just one signal, one hole, and one turn of the spade to unearth something virtually unique. However, this was not realised by the finder, Colin Popplewell, until he had posted images to an online forum. Further unbeknownst to him, his chance discovery would reignite a debate over the very existence of a third century usurper, and the contentious issue of his having struck coinage. The coin he found (Fig.1), provided an overt reference to a character by the name of Proculus having assumed the imperial purple. The legend reads:

IMP C PROCVLVS AVG // VICTORIA AVG

Emperor Caesar Proculus Augustus // Victory of the Emperor

This legend has only appeared once previously on a coin from a German collection, sold in 1991. Given its inherent rarity, it was unsurprising that this latest find was first met with scepticism, and then denunciation as a later forgery by some academic circles. However the author recalls a remarkably similar scenario occurring in the case of another usurper: Domitianus II. This case was only resolved in 2003, when a hoard from Chalgrove, Oxfordshire securely contextualized a coin bearing Domitianus’ name. Whilst a scenario such as this is yet to arise for Proculus, the reliable context of this second discovery compels my subsequent analysis to be conducted on the presumption that both examples are genuine.

|

| Figure 2: Both coins superimposed |

With only two coins, it would seem extremely difficult to produce a convincing argument for reinvestigation. However by overlaying images of one coin on top of the other, it is immediately apparent that the obverse and reverse designs are identical (Fig. 2). To a numismatist, this is a definitive indication that the same pair of dies produced both coins. This also strongly suggests that they were produced at the same workshop, if not even by the same hand (Morgan 2006: 175. For Domitianus II die linkages also proved crucial in authenticating both coins). Furthermore, the presence of intelligible legends on these two coins must indicate that they are also the product of a literate manufacturer. This particular factor also questions their potential alternative identification as so-called “barbarous radiates” (which also happened to be in contemporary circulation). However, most of these coins were low-grade imitations of official currency, and were seemingly produced by local, illiterate satellites. Consequently, the only plausible conclusion to draw from this appraisal of Proculus’ coinage is that they resemble the products of a coordinated and sanctioned series.

Having therefore established credentials for our coin, an assessment of other extant material can now be made, to establish whether this additional numismatic evidence for Proculus conforms to our historical impressions of the individual. The iconography of the coin itself helps to narrow our search of literary material to the later third century AD. This is evident from the size of the coin and the depiction of a radiate crown, which is emblematic of this period. Our main historical record for this period is the Historia Augusta, which is unfortunately notorious for its fabrication of stories (Dessau 1899). On account of its reputation, it is therefore unsurprising to find that it has provided two conflicting accounts for the character of Proculus. The first has him revolt in Cologne during the reign of the Emperor Probus (HA Life of Probus XVIII.5), whilst the second records his rebellion occurring in Lyon (HA Lives of Firmus, Saturninus, Proculus and Bonosus I.4, XIII.1). Other surviving references to Proculus are more questionable on account of their even later publication dates (Eutropius IX.17, Epitome de Caesaribus XXXVII.2). Consequently as the literary source most contemporary to the life of Proculus, the Historia Augusta must be consulted in contextual discussion of these enigmatic coins.

“One fact, indeed, must be known, namely, that all the Germans, when Proculus asked for their aid, preferred to serve Probus rather than rule with Bonosus and Proculus.”

HA Life of Probus XVIII.7

This suggests that Proculus usurped during the reign of Emperor Probus alongside a figure by the name of Bonusus, although no such indication of this partnership is given on our coins (the recognised dedication for multiple rulers is expressed by the number of Gs in ‘AVG’ - Proculus’ coinage has just one). More significant though, is the explicit mention of a location that accords with the find-spot of this latest example. Proculus is documented as having claimed the province of Britannia along with Gaul during his usurpation (HA Life of Probus XVIII.5), thereby assuming control of the Legion stationed in York (near to the site of the coin’s eventual deposition). However, in the view of the author, if the revolt had occurred during the reign of Probus, our examples of Proculus’ coinage would be stylistically out of date. This is owing to a coin reform enacted by Probus’ predecessor Aurelian, during the middle of AD 274 (Carson 1965, Weiser 1983). Alongside the addition of mintmarks and marks of metal or face value, the style of imagery depicted notably changed. Comparing the pre- and post-reform currency of Aurelian clarifies this point further, (Fig. 3 and 4) as design focus visibly shifts away from large draped busts to depictions of elongated necks wearing cuirassed attire. Whilst usurpation may have led to cessation of contact with the Empire, knowledge of monetary design appears to spread unaffected. Confirmation of this can be found in the usurper Saturninus, who apparently revolted in the East at the same time as Proculus did in the west (HA Life of Firmus, Saturninus, Bonosus and Proculus). His coinage (Fig. 5) depicts significant iconographic similarities to Aurelian’s reformed coinage, as the long neck and military uniform are his most noticeable features. Had Proculus’ rebellion been contemporary to Saturninus, one would expect to see more stylistic similarities between the two series. However, their style remains notably different, with Proculus’ strong facial dominance being more akin to pre-reform types. Consequently, iconography forces us to consider the possibility that Proculus coined, and thus usurped, much earlier than the literary sources suggest; prior to the Summer of AD 274.

|

|

| Figure 3: Pre-reform issue of Aurelian |

Figure 4: Post-reform issue of Aurelian

|

|

|

|

| Figure 5: AV Aureus of Saturninus |

Figure 6: Antoninianus of Tetricus

(AD 270-3), VICTORIA AVG, RIC V.2 141

|

Pursuing this theme further identifies a striking iconographic relationship between Proculan types and Tetrican coinage of the late Gallic Empire (AD 271-4). The depiction of a radiate crown alongside the stylistic rendering of the hair and beard seem, at first glance, to be virtually indistinguishable. There is however an unusual feature to Proculus’ coin that challenges the combination of the reverse legend and the personification depicted. The legend being whole on the new discovery confirms the personification to be related to ‘victory’. However there appears to be no reflection of Victoria’s most recognisable attribute (wings) on the figure itself. Yet, similarly dedicated Tetrican issues clearly depict these iconic wings alongside the legend (Fig. 6). The author however notices the remarkable similarity of Proculan imagery to Tetrican representations of Pax [Peace] (Compare Fig. 1 and 7). If such confusion is a sign of ignorance on the part of the die engraver, the rest of the coin design reflects only overt and literate skill. Consequently, iconology allows us to isolate a distinct relationship between the coinage of the Tetrican dynasty and Proculus, furthering the contention for a revisal of our current date for his revolt.

|

|

| Figure 1: Proculus reverse |

Figure 7: Tetricus Antoninianus

(AD 270-273) PAX AVG reverse

|

Intriguingly our other surviving literary reference to Proculus affirms this idea, by bizarrely also recording his revolt during the reign of the Emperor Aurelian:

“…to see to it that … Bonosus and Proculus and Firmus, who revolted under Aurelian, be not be passed over in silence.” (HA I.4)

Given this new date, earlier accounts need reappraisal in order to identify whether available evidence has been overlooked or even originally misrecorded. Given the previous association of Tetrican and Proculan coinage, the histories recounting the fall of Tetricus and the end of the Gallic Empire are of particular interest. They document how the Gallic usurper defected to Aurelian as a consequence of his inability to control his Legions’ ‘evil deeds’ (HA Life of Aurelian XXXII.3). The ambiguity of this account is problematic, as too is the implausible scenario of Tetricus simply defecting to Aurelian on account of his failure to discipline his army. Moreover, numismatic evidence clearly suggests that Tetricus had dynastic intentions for his own household, as he produced coins in the name of his son. This can only be perceived as a view to dynastic succession, thus directly contrasting with the notion of a voluntary, uncontested surrender. However, later histories allude to a mutiny within his legions at this time (Eutropius IX.13.1), and even the establishment of a rival usurper by the name of Faustinus (Aurelius Victor XXXV.4). Zonaras even adds that Aurelian succeeded in suppressing this usurper soon after receiving the surrender of Tetricus (Zonaras XII.27). Mutiny thus provides a more plausible explanation for Tetricus' surrender, as it implies that his actions were out of compulsion.

However the overall narrative is confounded by a lack of reference to the usurper “Faustinus” at any point in the Historia Augusta. Yet every indication from later sources imply that his reign lasted up to several months, easily affording him time to produce currency, especially if accounts accurately record the revolt at the Gallic mint site of Trier (Konig 1981: 181). Yet no such coins have ever appeared in the name of Faustinus and no account is provided for him in our most contemporary and complete text on third century Gallic usurpers. This history, however, strikingly resembles the picture thus far painted from a study of Proculus’ coinage. As previously argued, the idea of Proculus being the rival usurper who drove Tetricus out in AD 274 also fits significantly better with the coin iconography he displays. Such a narrative would also account for the significant rarity of Proculus’ coinage, as Aurelian was already marching on Gaul to remove Tetricus at the time of this subsequent revolt. Circumstantial evidence may therefore tempt us to entirely replace the character of Faustinus with Proculus, but neither exists on mutual exclusivity. Nevertheless, literary material still allows us to tentatively advance our knowledge on the figure of Proculus. Histories clearly indicate that a revolt occurred in Gaul at the end of Tetricus’ reign, prompting his downfall. Given the further existence of textual and iconographic data that plausibly attribute Proculus’ rebellion to this time, and to this location, Colin Popplewell’s find provides us with a new and significant opportunity to reconsider the date for this most enigmatic of usurpers.

Must it truly take one coin, in one hoard, to truly return Proculus to the annals of history?

Written by Greg Edmund, an Undergraduate Finalist at the University of Warwick, studying Ancient History. His interests are in Ancient and Medieval Numismatics.

Bibliography:

Carson, R.A.G (1965) ‘The reform of Aurelian’, Revue Numismatique, Vol.6, No. 7, pp225-235

Dessau, H (1889) ‘Uber Zeit und Personlichkeit der Scriptores Historiae Augustae’, Hermes 24, pp337-392

König, I (1981) Die gallischen Usurpatoren von Postumus bis Tetricus (München)

Morgan, L (2006) ‘Domitian the Second?’, Greece and Rome Vol 53, No.2, pp175-184

Weiser, W (1983) ‘Die Münzreform des Aurelians’, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 53, pp279-295

Figures:

Figure 1: DNW Auction (10 April 2013) Lot 694.

Figure 2: Umberto Moruzzi and Fabio Scatolini ‘The usurper Proculus and his coinage’, Coins Weekly [Accessed: 30th January 2016)

Figure 3: Aurelian pre-reform radiate: RIC 29 (http://www.wildwinds.com/coins/ric/aurelian/RIC_0029.jpg) [Accessed: 22nd February 2016]

Figure 4: Aurelian post-reform radiate (http://www.coinshome.net/) [Accessed: 22nd February 2016]

Figure 5: Dirty Old Coins (http://www.dirtyoldcoins.com/roman/id/Coins-of-Roman-Emperor-Saturninus.htm) [Accessed: 30th January 2016]

Figure 6: Wildwinds (http://www.wildwinds.com/coins/ric/tetricus_I/RIC_0141.1.jpg) [Accessed: 30th January 2016]

Figure 7: Wildwinds (http://www.wildwinds.com/coins/ric/tetricus_I/RIC_0100.jpg) [Accessed: 30th January 2016]

February 01, 2016

A silver stater of Evagoras in the British Museum

|

The political turmoil in the Greek world at the end of the Peloponnesian War provides the context for cultural changes of which this silver stater, produced for Evagoras I, ruler of the Cypriot city of Salamis from 411 to 374 BCE, is material evidence. Evagoras negotiated a tricky career with challenges both at home and in negotiating and maintaining relationships with Greek cities and the Persian empire. One of the remarkable things about Evagoras is the range of evidence about him and his career, from mentions in Athenian rhetorical, historiographic and philosophical texts, to inscriptions from both Athens and Salamis itself, to the gold and silver coins with which he established an identity for his city.

Evagoras’ coinage provides evidence for an intriguing cultural mixture and period of change. His coinage, of which this silver stater is a representative example, features the Greek hero Heracles on the obverse and a goat and a grain of corn on the reverse. The rather wild, bearded Heracles wears his lion skin as a head-dress, its legs knotted around his chin (perhaps a way to get the iconic garment into the format of a coin portrait?); the text, in Cypriot syllables, gives his name E-u-wa-go-ro. The iconography with its reference to Greek hero myth reinforces the Salaminian rulers’ claim to a Greek cultural heritage, also expressed through their legendary descent from Teucer. The text of the reverse asserts Evagoras’ authority of king (ba-si-le-wo-se), mixing Cypriot syllables with the occasional Greek letter, showing that the transition to a more emphatically Hellenic identity was in progress but incomplete.

As the fourth century progressed, subsequent rulers would adopt Greek letters for their coinage (Hill, McGregor); Evagoras, in whose name the earliest civic inscription using both Greek and Cypriot writing was issued, used both forms of writing. This coin catches an early stage in a transition to Greek script that would be completed by his successors.

For the Athenian educator and moralist Isocrates, Evagoras was a paradigm of the virtuous ruler. Praising his achievements in a florid encomium, Isocrates presents a story of a courageous and determined individual who surpasses the achievements of his mythical ancestors in retaking his city, as he did in 411 BCE, the start of what Hill describes as ‘a period of Hellenic revival’ (Hill 1904: c-ci). Evagoras campaigned with Conon, for which he was honoured by Athens, but in attacking other Cypriot cities attracted the unfavourable attention of Artaxerxes, great king of Persia, and by the 370s had to submit himself and his city to Persian control.

Isocrates passes over the rather squalid circumstances of the end of Evagoras’ career, his assassination by a eunuch in 374 BCE after a court intrigue (although his Nicocles 31 may refer to it: see also Aristotle Politics V.10.1311b4-6, Diodorus Siculus 15.47.8), and indeed spins his earlier role as provider of bolt-holes for fugitive Athenian politicians such as Andocides (Lysias 6.28) and Conon (DS 13.106.6) into praise for Salamis’ ability to attract a high class of immigrants (Evagoras 51-2). And there are further divergences between the literary and material record – Marguerite Yon (Yon 1993: 144-5) reports that extensive excavations at Salamis have not uncovered Evagoras’ buildings, praised by Isocrates (Evagoras 47), although archaeologists have found epigraphic records, including a fragmentary inscription with text written in both Greek letters and Cypriot syllabic symbols.

Isocrates was not a historian or even a biographer; his depiction of Evagoras is a work of patterning and invention, containing some of his most interesting thought on the nature of monarchy. It, along with its companion piece Nicocles, is an early example of an Athenian taking interest in a form of rule that would become more important as the fourth century BCE progressed and other monarchs from the fringes of the Greek world, with their own mythical ancestor stories, would claim the attention of the Athenians rather more aggressively. Spatially and politically, Evagoras’ Salamis lay between Greek and Persian areas of influence. The city, which Evagoras ruled as tyrant (Isocrates Evagoras 32) or king (Evagoras 39, IG II2 20.6, 16), depending on your analysis of monarchy, was, as Evagoras’ life shows, caught between the political and cultural influence of the Greek and Persian worlds, but it also had its own distinctive culture.

Isocrates was not the first Athenian to praise Evagoras, nor the last to find him interesting. The Athenians voted him first citizenship (IG I3 113, c.411 BCE) and then further honours and a statue for the help he had provided to Conon (IG II2 20, 394/3 BCE; Rhodes and Osborne 11). Athens needed all the friends it could find, during both the later phases of the Peloponnesian War and the period in which the restored democracy sought to re-establish Athenian interests in the Aegean and Mediterranean. But its grant of such honours to the ruler of a different kind of polity perhaps shows Athenian realpolitik in action.

This month's piece was written by Carol Atack. Carol is a Senior Teaching Fellow in Greek Cultural History in the Department of Classics and Ancient History; her primary research interest is in ancient Greek political thought, and particularly the monarchical thought of Xenophon and Isocrates.

References

Iacovou, M. (2013) ‘The Cypriot Syllabary as a royal signature: the political context of the syllabic script in the Iron Age’, in P.M. Steele (ed.) Syllabic Writing on Cyprus and its Context (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), pp. 133-152.

Hägg, T. (2012) The Art of Biography in Antiquity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), pp. 30-41.

Hill, G.F. (1904) Catalogue of the Greek coins of Cyprus (London: British Museum).

Lewis, D.M. and Stroud, R.S. (1979), 'Athens Honors King Euagoras of Salamis', Hesperia, 48 (2), 180-93.

McGregor, K.A. (1999), 'The Coinage Of Salamis, Cyprus, From The Sixth To The Fourth Centuries B. C.', (Unpublished PhD thesis, University College, London).

Rhodes, P.J. and Osborne, R. (2003) Greek Historical Inscriptions: 404-323 BC (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Roesch, P. (1973) ‘Une inscription digraphe du Ve S. av. J.C.’, in Institut Fernand-Courby, Anthologie salaminienne: Salamine de Chypre, Vol. 4, Paris: E. de Boccard), pp. 81-84.

Yon, M. (1993), 'La ville de Salamine: Fouilles françaises 1964-74', in M. Yon (ed.), KINYRAS: L'Archéologie française à Cyprus : table-ronde tenue à Lyon, 5-6 novembre 1991 (Lyon: Maison de l'Orient), pp. 139-58.

Image © Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

January 01, 2016

Numismatics: the role of the Praetorians in the accession of Claudius

|

RIC I2 Claudius 7

Date: AD 41 - AD 42

Denomination: Aureus

Mint: Rome

Obverse: TI CLAVD CAESAR AVG P M TR P (Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus, Pontifex Maximus, Holder of Tribunician Potestas). Head of Claudius, laureate, right.

Reverse: IMPER RECEPT (Imperator/Emperor Received). Battlemented wall enclosing praetorian camp; inside, soldier, holding spear, right; in front, aquila; behind, pediment with flanking walls.

Claudius rose to the position of Emperor in AD 41, after the assassination of Caligula in a conspiracy including the Praetorian commander Cassius Chaerea. Suetonius writes that a terrified Claudius took refuge by hiding in the palace (Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 19.3). Claudius was found by the Praetorians, carried to their camp, and it was here that Suetonius reports Claudius spent the night in terror. On the following day the Praetorians chose to swear allegiance to Claudius as their newly elected emperor.

With this knowledge the coin takes on a completely different meaning from first glance, and gains far more significance (Crawford (1970) 265). It explains the iconography on the reverse of the coin, portraying the Praetorian camp, where Claudius was sworn in as emperor. The image behind the wall represents a Praetorian soldier holding a spear standing beside an aquila or “standard”. This offers an insight into the strong relationship between the Praetorian Guard and Claudius. This coin perfectly captures the change in attitude of Claudius, from Suetonius’ description of him fearing for his life at the hands of the Praetorians to instead displaying them as a symbol of safety, security and prosperity.

The Praetorian Guard, however, is shrouded by controversy in modern studies. Overall, they have received relatively little scholarly attention, yet it is almost unanimously accepted by scholars that the Praetorian Guard were used in supporting emperors’ often “ruthless” regimes (Rankov (1994) 3). This is an idea furthered by Levick’s reading of Josephus’ account, that the senate considered Claudius had seized the position of Emperor, condemning him in their eyes as a hostis or “public enemy” in much the same way as Mark Antony after the battle of Actium (Levick (2015) 40). However, with the support of the Praetorians the senate had little choice but to accept Claudius as Emperor. The power of the Praetorians is evident in this historic narrative and neatly summed up in Josephus when Veranius and Brocchus beseech Claudius not to accept the Praetorians’ backing in taking the position of emperor:

Now these ambassadors, Veranius and Brocchus, who were both of them tribunes of the people, made this speech to Claudius; and falling down upon their knees, they begged of him that he would not throw the city into wars and misfortunes; but when they saw what a multitude of soldiers encompassed and guarded Claudius, and that the forces that were with the consuls were, in comparison of them, perfectly inconsiderable, they added, that if he did desire the government, he should accept of it as given by the senate; that he would prosper better, and be happier, if he came to it, not by the injustice, but by the good-will of those that would bestow it upon him.

Josephus Antiquities of the Jews 19.4

There are clear parallels with Claudius’ rise to the position of emperor and that of Julius Caesar’s: both relied on strength of arms, although seizing power could arguably have brought great danger to Claudius. The speech of Veranius and Brocchus also draws a comparison of Claudius with “former tyrants” who had caused great afflictions to their cities (Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 19.3). It would be easy to assume Claudius would want to distance himself from being seen as too powerful, something that may have contributed to the assassination of Julius Caesar. However, it is incredibly interesting that Claudius does not attempt to obscure the way he came to power; rather he advertises the support of the Praetorian Guard on pieces that include this coin (Levick (2015) 43-4).

The motive of the Praetorians becomes clear when we look at Suetonius, who explains that Claudius was the first Emperor to purchase the submission of the soldiers with money, promising fifteen to twenty thousand sesterces to each member of the Praetorian guard (Suetonius, Claudius 5.10). Tacitus mentions that the Praetorians rose in number from 9 to 12 cohorts in AD 47. Each cohort comprised one thousand soldiers; so assuming nine thousand soldiers at fifteen thousand sesterces each, Claudius would have been giving in the region of 135 million sesterces. The enormity of this donation may also have had a profound impact on the Urban cohort, undermining their loyalty to the senate through a sense of envy (Levick (2015) 37). Yet many coins minted at the beginning of Claudius’ reign in AD 41/42 display extremely similar iconography and it is easy to assume that a large number of these coins would end up in the hands of the Praetorians. This seems to be a clever reminder from Claudius to each soldier of the importance of the Praetorians to his rule, and a somewhat subtle attempt to avoid a similar ending to Caligula.

Here we have a perfect example of an emperor who clearly owed his rule to the praetorians and by examining the coins and literary sources there can be no doubt about the significance of the Praetorian Guard in this episode of Roman history.

|

This month's coin was written by Miles Pearce. This is his first year at Warwick; he previously read Classics and Ancient History at Lampeter University. He is currently studying Ancient Visual and Material Culture at Masters Level, and so far has found a particular interest in reception of Greek myth in Renaissance art. However, his main interest is the Praetorian guard and their political influence.

Bibliography

December 01, 2015

A Word’s Worth: The Electrum Stater of Phanes

|

| Electrum stater of Phanes |

This electrum stater was minted toward the end of the seventh century BC in western Asia Minor. The obverse depicts a grazing stag and bears the retrograde legend ΦΑΝΟΣ ΕΜΙ ΣΕΙΜΑ, “I am the marker of Phanes”. The reverse has three rectangular incuse designs with decussate lines.

As one of the earliest examples of European coinage bearing an inscription, the stater of Phanes helps us understand how our modern currency works: it is dependent on promises. Phanes’ stater was made of electrum, an alloy of gold and silver, making it highly valuable. However, that worth was not easily determined from just weighing it since gold and silver had different values, and one could not be sure of the gold: silver ratio in this particular coin. That means that this coin was of an unknown intrinsic value. However, with the introduction of the inscription, the minter gives a guarantee of the coin’s worth; in fact he stakes his own name on its value. The ancient Greek word “sēma” means “sign”, meaning the inscription reads “I am the sign of Phanes”. The legend makes the coin’s value representative of Phanes’ own wealth and reputation. Hence Phanes vouched for the value of any coin that bore this inscription, guaranteed against the fortune of which it was a part. This need for a guarantee of the value may reflect a mistrust in the consistency of unmarked contemporary electrum coins. Indeed, the continuation of the use of legends to provide provenance and accountability for minting shows the effectiveness of the legend as a guarantee in contrast to unembellished coinages. We can say that from such an early point in numismatic history, value and inscription were inseparable, in fact dependent upon one another. It is the legend that gives the coin its guaranteed value and it is the tangible value of the electrum that makes the guarantee of such a rich man worth anything at all.

|

| Detail of modern day banknote |

This highlights the issue of modern banknotes. Paper money was first made in the ninth century AD during the Song Dynasty in China. It was created due to a shortage of copper (from which the state struck its coins), so instead the state issued paper on which were written promises to pay the bearer a specific sum at a later date. Indeed this is what it says on modern English banknotes today: “I promise to pay the bearer on demand the sum of X pounds”.

In the same way that Phanes promised a standardised value to this coinage, the Bank of England now guarantees the same on its banknotes. However, in modern times these written promises are traded as real money; there is no expectation that at a later date you will trade it in for coins or livestock of equivalent value. However, unlike Phanes’ stater, the paper (or rather polymer) on which modern money is printed has little or no intrinsic value. Intrinsic value and promise have been separated, and precious metals, which characterised early coinage, have disappeared from modern currencies. Rather it is the words guaranteeing the value of the currency that have proven more important and ultimately more valuable than gold or silver.

This shows how value is an imaginary idea determined subjectively by individuals as well as collectively by a community. This is a point that Aristotle picks up on in his Nicomachean Ethics V, v, 10-16:

money has become by convention a sort of representative of need; and this is why it has the name ‘money’ (nomisma)- because it exists not by nature but by law (nomos) and it is in our power to change it and make it useless. (trans. Ross 1980)

Ultimately a coin or banknote is only worth as much as you promise that it is worth. Try telling your bank that.

|

This month's coin entry was written by Nick Brown. Nick is a first year MPhil/PhD student in the Department of Classics and Ancient History at Warwick. His PhD is a study of inscribed statues in the Archaic and Classical Periods in Greece. His academic interests focus on the theme of image and text, ranging from art and inscriptions of the Archaic period to the ekphrastic literature of the Second Sophistic.

Coin image © Trustees of the British Museum (see the coin in greater detail at the Google Cultural Institute).

November 01, 2015

Otho's Victory: Wishful thinking, or genuine historical record?

Marcus Salvius Otho was the second of the emperors of AD 69, the infamous ‘Year of the Four Emperors’. Thanks to biographies by Plutarch and Suetonius, and historical accounts by Tacitus, Josephus and Cassius Dio, we know quite a lot about his time in power, even though it lasted for only three months from January to April AD 69.

In spite of the brevity of his reign Otho produced a very large coinage of silver denarii. The coins are not uncommon today, and are well-known to specialists. There are also issues for him in gold but, famously, no base metal coinage was issued for Otho at Rome (though some was struck in his name at the provincial mints of Antioch and Alexandria).

His denarius coinage is remarkably complex and comprises at least three phases. On the first the emperor’s praenomen is included (IMP M OTHO CAESAR AVG TR P). On the second the praenomen is dropped (IMP OTHO CAESAR AVG TR P), but reverse types introduced in the first phase continue. The third records him as Pontifex Maximus with the reverse legend PONT MAX and a new set of reverse types are introduced. There was also a reduction in the silver content of the coinage with the beginning of the third phase. Clearly the mint of Rome was very busy during Otho’s three months in power.

|

| Denarius of Otho from Rome (RIC I2 no. 17). |

The coin illustrated above belongs to the first phase:

IMP M OTHO CAESAR AVG TR P. Bare head of Otho right.

VICTORIA OTHONIS. Victory standing left on globe, holding wreath and palm branch.

This reverse type is found on coins of the first phase only. There is an identical type, with the legend VICTORIA P R, for Otho’s immediate predecessor Galba (AD 68-69), who was overthrown by Otho on January 15, AD 69. It looks as if Otho had appropriated Galba’s design. However, he may have done more than that. If we look very closely at the details on the reverse of this coin we can see traces of the letters P R underlying the word OTHONIS (figs. 2 and 3).

|

|

What does this mean? The most likely explanation is that the die used to strike this coin originally read VICTORIA P R, and it was re-engraved to read VICTORIA OTHONIS. It was presumably a die that had either been used for Galba’s coins, or was intended for use under Galba. The message was changed from the ‘Victory of the Roman People’ to ‘Otho’s Victory’.

Such an economy is certainly unusual, and raises further questions. The re-use of a die of Galba, and the fact that this type is found only in the first phase of Otho’s coinage, could suggest that this type was the first to be issued during his brief reign. Does it imply that Otho was in a hurry to mint coins in the very first days of his rule? But if so, what victory (or hoped-for victory) does it celebrate?

One might assume that it expressed the wish that Otho would prevail over his rival for supreme power, Vitellius. Shortly before Otho’s coup in Rome Vitellius had been proclaimed emperor by the German legions. However, Tacitus’ narrative makes clear that at the very beginning of his reign Otho was unaware of Vitellius’ bid; even after he received the news he hoped to avert civil war through negotiation with his rival. Eventually it became clear that war could not be averted and Otho was forced to take to the field, but this does not appear to have been a pressing concern right at the start of the reign; and would a coin type expressing Otho’s victory over fellow citizens be a palatable message for an emperor whose reign was not secure?

There is an alternative explanation of the type. On the March 1, AD 69, Otho celebrated a more acceptable victory: the legio III Gallica’s defeat of the Rhoxolani in the Balkans. It was a genuine victory, and it was a victory over barbarians, although Otho obviously had no part to play in it personally. Nevertheless the right to celebrate the victory belonged to the emperor, and Tacitus noted how delighted Otho was with this success.

This interpretation, though appealing, is not without problems. If VICTORIA OTHONIS belongs at the beginning of Otho’s coinage, it would mean that between January 15 and the end of February Otho struck no coins at all, and all of his coinage would need to be squeezed into a period from about March 1 to April 19 (the day when news of Otho’s defeat and suicide reached Rome). Some students of the coinage of this period have pointed to the huge number of dies used to produce this coinage (perhaps more than 1,000 obverses) to argue that it would have been impossible for the mint of Rome to have produced such a vast output of coinage in a mere 51 days or so. It is, of course, hard to guess the capacity of the Roman mint: we have no figures for any period of Roman coinage. It might seem preferable to assume that, if VICTORIA OTHONIS does belong at the beginning of Otho’s coinage, it was issued in January, shortly after Otho’s coup, which would give us a duration of about 94 days for the coinage. However, some commentators have pointed to a potential problem (aside from the question of which victory is commemorated): all of his denarii bear the title TR P. The formal grant of tribunician power took place on the last day of February, AD 69, just before the victory celebration. It is unclear whether Otho, as a usurper, would have advertised this power without it being conferred on him formally, although it has been argued that the senate passed some kind of act allowing Otho to assume these powers on the very day of his coup on January 15.

War slogan or witness to history? By itself a coin such as this one cannot provide a clear answer, but it shows how even minute details can raise questions about familiar and well-known coinages and how these could have wider consequences for our understanding of the period.

This month's coin was written by Kevin Butcher. Kevin is currently completing work on a three-year AHRC-funded project in collaboration with Dr. Matthew Ponting of the University of Liverpool, investigating the metallurgy of Roman imperial and provincial silver coinages from Nero to Commodus, and will shortly begin work on the Cambridge Handbook to Roman Coinage. He is also interested in the application of social theories in archaeology, particularly with regard to material culture and the ancient economy. He has worked on several excavation projects in the Mediterranean and published the coin finds from several major ancient sites, including Nicopolis ad Istrum in Bulgaria and Beirut in Lebanon.

October 01, 2015

The elephant denarius of Julius Caesar

|

|

Silver denarius of Julius Caesar (RRC 443/1)

One of Julius Caesar's most famous coin issues is the ‘elephant denarius’. The reverse features a group of religious symbols: a culullus, aspergillum, an axe decorated with animal imagery, and an apex. On the obverse, the denarius shows a right facing elephant with the word "CAESAR" in the exergue. An estimated 22.5 million pieces were minted, making this coin the third most frequent in the Republican era and adequate to pay eight legions. It is often dated to 49 B.C, the year Caesar took large quantities of gold and silver from the treasury in the Temple of Saturn in Rome. This metal was probably used to fund his new denarius. The date is one among the questions about the coin that continue to be debated. Other undecided issues include what the elephant is standing on.

The elephant may symbolize Caesar's Gallic campaign against Ariovistus in the battle of Vosges in 58 BC, especially if the object on which the elephant treads is a Gallic war trumpet. But this object could arguably be a snake, meaning that the coin communicates the victory of good over evil. Among other propagandizing purposes, it could have been intended to humiliate the self-important and supercilious Pompey, who had tried to associate himself with Alexander by riding a symbol associated with Alexander the Great, the elephant, in his triumphal procession. Pompey had, embarrassingly, failed to actually manoeuvre the animal into the city. The image might represent the snake as a natural enemy of the elephant.

The religious symbols associate Caesar with his prestigious pontifical position as the head of Rome's religious hierarchy. Caesar had been Pontifex Maximus since 63 B.C. The symbols are similar to the augural ones that are more common on Republican Roman coins, including the lituus. Because Caesar did not become an augur until 47 B.C, and since the coin is dated to, at the earliest, the 50s, or more likely 49, it should be noted the symbols here are not augural.

However the view of some scholars suggest that the imagery of the elephant suggests that Julius Caesar considered himself on the same footing as famous military generals such as Alexander the Great and Hannibal.

|

This month's coin was written by Alfred Wrigley. Alfred is a 2nd Year Ancient History and Classical Archaeology student with great interest in Julio-Claudian Numismatics and is hoping to specialise in numismatics of Julius Caesar.

Coin image reproduced courtesy of the American Numismatic Society.

September 01, 2015

Dionysiac Dolphins: coinage and social identity

|

| Dolphin coin of Olbia (SNG BM Black Sea 360) |

This dolphin-shaped money was found at Olbia, a trading colony of Miletus on the coast of the Black Sea, and dates from the late sixth century. The coins are made of bronze, and are approximately 35mm in length. Archaeologists believe the use of these pieces to be monetary because they carry leaders’ names and are found in hoards and in tombs. Although the dolphins were eventually replaced by more conventional round currency which incorporated the image of a dolphin into its design, the dolphin shape builds on a Greek tradition of using dolphin iconography as a way of representing the internal struggle to define identity in the face of increased interaction with foreign culture.

Dolphin imagery is used in both literary and artistic depictions of Greek culture in the time of colonisation, embodying the separation between Greece and the outside world. The distinction between self and other played an increasingly important role in the lives of Greeks as colonisation and trade grew. The need for outside materials such as grain (which did not grow well in Greece) or metals and the need for land (a requirement for citizenship) increased awareness of the cultural and linguistic differences between Greeks and non-Greeks. This heightened the urgency with which the Greeks began to define themselves.

|

|

Dionysus sailing surrounded

by dolphins.

|

One literary depiction of the dolphin is in Herodotus (1.23): a dolphin rescues Arion from death at the hands of rogue sailors during a war against Miletus. The Histories are full of contrasts: home and away; barbarism and civilisation. This story uses these contrasts to explore the dichotomous and fraught relationship Greece was developing with the outside world. The dolphin in this instance represents a protector of civilisation by rescuing the creator of dithyramb (a sympotic song, sung in honour of Dionysus): a core part of the established social patterns of Greek culture. Although the sailors were also Greek they demonstrate a loss of civility having left behind the civilisation of Greece: once Arion returns to Greece, he is again honoured.

Archilochus discussed the opposition between land and sea, creating a sense of opposition between the safety of Greece and the uncertainty of sea-faring: “the forest beasts remove to dolphins’ salty fields, finding roaring waves a sweeter home than land” (122W). Although this colonisation is not the primary context of the fragment, the use of contrast and sea imagery clearly references the use of the sea to explore new territory. Contextually, this poetry would be performed at symposia and perhaps not in the traditional sense: Carey (2009) notes the possibility that the symposium was removed to the ship – the performed lines reflect the literal situation of the sailors, allowing them to define themselves as a group separate to Greece, using the habitat of the dolphins to create a home-away-from-home for themselves.

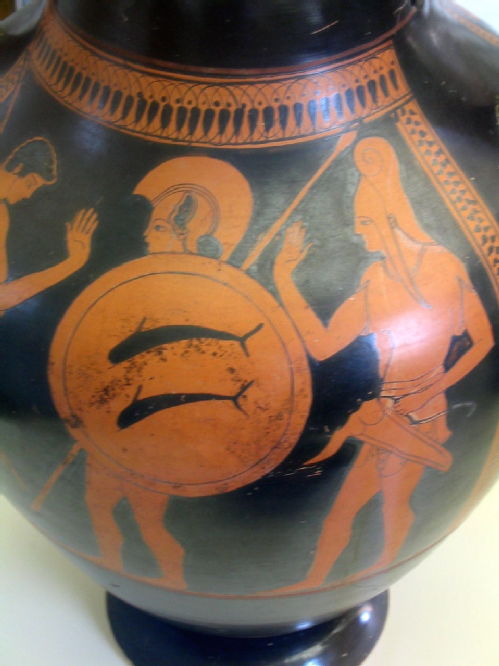

|

| Hoplite warrior

with shield

|

In art, the use of the dolphins is also connected to the symposium: Dionysus rides through the sea on a boat surrounded by dolphins, with vines growing above his head. The idea of nautical transportation not only connects to colonisation, but also to the “long distances” drinkers traversed through wine (Davidson, 1998). The symposium offered a space for self-discovery, performance of the self, and exploration of the new world the Greeks were facing. The symposium is linked intrinsically to the story of Arion, creator of the Dithyramb through the musicality and theatricality of the symposium, the dolphins acting as a “visual projection of dithyrambic chorality” (Kowalzig, 2013). Dolphin iconography here then demonstrates both the physical and mental transportation of Greek cultural awareness and definition.

In other vases, dolphins appear in the context of warfare, playing antipathetic roles of protection and attack. In the context of the hoplite, the dolphins are seen being ridden into battle, and also on the shield: they are figured as a Greek asset, turning the sea into a battlefield both physically in the form of naumachy but also figuratively in terms of the mental battle between need for expansion and will for Hellenist isolation. The sea is being claimed as Greek through the appropriation of the dolphin.

|

|

Hoplite warriors riding

dolphins into battle.

|

The use of dolphin iconography in the Olbian coin can arguably be considered to be about identity. Although the evidence discussed so far has explored how the Greeks used the dolphin to figure their identity, this is also an important question for a colony with significant outside interaction from trade. Olbia is not the only colony to use the dolphin image in this way: Taras, the only colony founded by Sparta, used the image of a dolphin-rider on their coins, perhaps to emphasise the militaristic connection to Spartan society. The dolphin allows a connection to be made to Greek culture through sympotic and competitive ideals drawn from the literary and artistic tradition. There are also links to the temple of Apollo Delphinos, again demonstrating the prioritisation of the Greek connection for the colony. However, it also allowed Olbia to create its own separate identity. Dolphins inhabit the physical space between Greece and her colonies; by highlighting this gap the colony emphasises its otherness. Olbia also created a law insisting that all trade took place in Olbian currency, although this came later at c.350BC, suggesting that at all points in the colony’s history independent identity was important for a colony with so much foreign interaction. The dolphin coin, with precedence in Greek culture, allowed Olbia to create her own identity separate to Greece and separate to Miletus.

This month’s coin was written by Lucinda Hughes. Lucinda graduated from Warwick in 2014 with a BA in Classical Civilisation, which gave her a continued interest in Greek and Latin literature. She is now studying for an MSc in Business (Finance and Accounting) at Warwick Business School, and begins work at Nomura International in September.

Select Bibliography:

Carey, C (2009) "Genre, Occasion and Performance", in The Cambridge Companion to Greek Lyric, eds. Budelmann (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge).

Davidson, J. (1998) Courtesans and Fishcakes (Fontana Press, London).

Kowalzig (2013) “Dancing Dolphins on the Wine Dark Sea” in Dithyramb in Context, eds. Kowalzig and Wilson (Oxford University Press, Oxford).

Images:

Dolphin coin: © Trustees of the British Museum.

Plate showing Dionysius: "Exekias Dionysos Staatliche Antikensammlungen 2044" by Exekias - MatthiasKabel, Own work, 28 January 2006. Image renamed from Image:Dionysos Augenschale des Exekias.jpg. Licensed under CC BY 2.5 via Commons.

Amphora depicting hoplite warrior with shield: "Athenian red figure Amphora" by Dan Diffendale, own work, 2 September 2005. Licenced under CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Hoplite warriors riding dolphins into battle: Reproduced courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, "Terracotta psykter (vase for cooling wine) attributed to Oltos, accession no. 1989.281.69.

Clare Rowan

Clare Rowan

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…