All 4 entries tagged Spintriae

No other Warwick Blogs use the tag Spintriae on entries | View entries tagged Spintriae at Technorati | There are no images tagged Spintriae on this blog

June 01, 2020

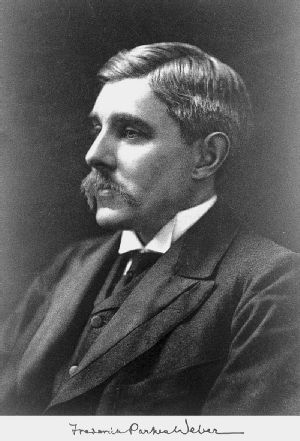

Frederick Parkes Weber and the Bowl of Coins Prize

|

|

|

Frederick Parkes Weber,

|

Interesting Cases and Pathological

Considerations.

|

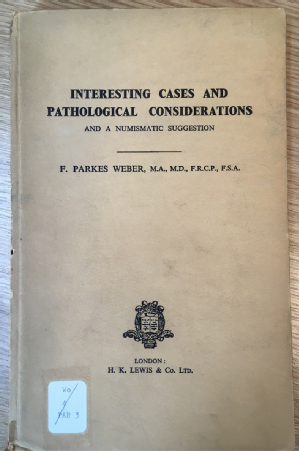

Amongst the papers of the famous dermatologist Frederick Parkes Weber now housed in the department of Coins and Medals in the British Museum is a book rather intriguingly entitled Interesting Cases and Pathological Considerations and a Numismatic Suggestion. While most of the book will not interest the student of coinage, the ‘numismatic suggestion’ appended at the end provides a great insight into Weber’s knowledge of ancient coinage (he was an avid coin collector) and the Royal Numismatic Society’s Parkes Weber Prize, currently awarded to the best essay ‘of not more than 5,000 words on any subject relating to coins, medals, medallions, tokens or paper money’ written by someone under 30.

The numismatic suggestion (photographs of the text available to read here and here) records that originally Parkes Weber proposed to the Royal Numismatic Society (RNS) an annual ‘bowl of coins’ prize. The idea came to him since, as a collector, he had to frequently quickly assess bowls of coins from various dealers across the world. The council found the suggestion impractical, and so instead implemented the prize in its current form. But it appears that Parkes Weber was not happy with the solution, and so published his original letter of 1st October 1953 to the President of the Royal Numismatic Society ‘in the hope that at some future time my suggestion will be carried out by a society of private donor. I believe that a small analogous prize is being offered to postage stamp enthusiasts with considerable success.’

Reading the letter, Parkes Weber originally proposed to the RNS an annual prize of 10 guineas to young collectors for ‘the best written diagnosis (with half an hour) of the contents of a bowl of miscellaneous coins and coin-like objects (twenty pieces in the bowl) under the supervision of a delegate of the Society in question’. He suggests they should all be good or moderately good specimens, as well as one or two imitations. He then goes on to offer detailed advice on what this ‘bowl of coins’ should contain.

Parkes Weber suggested the bowl should contain two or three counters or admission tickets (e.g. the Nürnberg Rechenpfennige, the card counters struck on the accession of Queen Victoria with the Duke of Cumberland on horseback on the reverse). He also suggests the inclusion of Greek and Roman tokens, including the so-called spintriae. These tokens carry sexual imagery on one side and a number on the other: Parkes-Weber includes the now discounted idea they were used as brothel admission tickets. He then notes that a fellow collector gave him two spintriae because the collector ‘did not like having them in his collection, when he was showing it to ladies’. Two bronze Roman tokens from the Parkes Weber collection are now in the British Museum, although only one shows an erotic scene.

|

|

'Spintria' in the British Museum once owned by Parkes Weber.

The obverse shows a scene of sexual intercourse and the reverse

carries the number III within a wreath. © The Trustees of

the British Museum, 1906,1103.2927.

|

Parkes Weber writes that only five of the twenty coins in the bowl should be of very rare or obscure types, and suggests specific coin types for ‘occasional admission to the bowl’. These include a copper coin of the Seljukian Turks with types copied from Byzantine Christian pieces, a coin of Edessa ‘preferably a coin of Count Baldwin II with the slashing horseman reminding one of the Norman knights on the Bayeux tapestry’, a coin weight of Charles I struck by Briot, school tokens of the seventeenth century, the ‘dolphin coins’ of Olbia, medieval and modern badges, and Russian beard tokens and prison tokens. Reading the list, one is struck by the interest and knowledge Parkes Weber had of tokens from all ages.

There is, despite the publication of the letter (admittedly in a venue which may not be frequently read by numismatists) still no ‘bowl of coins’ prize. But it does make one think about what types of coins and money might make up the bowl today!

This blog was written by Clare Rowan as part of the Token Communities in the Ancient Mediterranean project.

August 17, 2017

Gaius Mitreius, Magister Iuventutis, and the Materiality of Roman Tokens

Amongst the ancient tokens kept in the coin cabinet of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford is this piece struck from brass (orichalchum). One one side is a male bust (perhaps of Mitreius or more generally a representation of "youth") surrounded by the legend C. MITREIVS L. F. MAG. IVVENT - Gaius Mitreius, son of Lucius, master of the youth (the iuventutes was a youth organisation). On the other side is a two-story building with columns that looks very much like a basilica. On the building is inscribed L. SEXTILI∙ S.P. = Lucius Sextilius, at his own expense.

|

|

Token from the Ashmolean Museum (Oxford). (20mm, 3.58g, die axis 6).

In his analysis of Roman tokens Rostovtzeff discusses this type (p. 60), noting that the example in Paris has a countermark underneath the bust. This piece has the number X (10) etched into the exergue on the reverse, but other specimens carry the numbers VIIII and IIII. The structure on the reverse also varies on different examples (as is typical of numismatic representations of buildings) - other representations show a more circular structure that has been identified as an amphitheatre. The representation of the same or similar scenes with differing numbers is reminiscent of the famous spintriae, bronze tokens that carry sex scenes on one side and differing numbers on the other. The fact that the numbers appear to be incised into the token after it was struck is also similar to a practice known in late antiquity, where contorniates (late antique tokens whose purpose remains debated) where inscribed with Christian symbols, palm branches or other designs after striking. One example of this practice is shown below on a piece from the British Museum: a palm branch has been etched into a contorniate that shows Homer on one side and Bacchus on the other.

|

We don't know anything further about the Lucius Sextilius named on the token, nor about Mitreius beyond the fact that he held an office connected with the iuventutes, the youth organisations that existed in the western part of the Roman Empire (also known as collegia iuvenes). But we do possess inscriptional evidence for the Mitreius name at Rome and in Gubbio (CIL VI, 28976 and 38641, CIL XI, 5861, AE 1988, 347). A Mitreius token like that shown above was reportedly found on the island of Capri, although this specimen is now lost (Federico and Miranda 1998, 363).

This was not the only token struck by Mitreius in connection with his position as magister iuventutis. He also struck a type with the same obverse (a male bust and his name) with a facing lion's head within a wreath on the reverse. Other bronze types carried the same obverse with a number within a wreath on the reverse (IIII, XI and XII are known - Cohen VIII 12-15, and Triton IV, 449, the specimen pictured below) - this again is very similar to the design of spintriae. Another specimen, now in a private collection, carries Mitreius' name and a tripod on one side and two clasped hands with a poppy seed on the other - this token also appears to be countermarked in the image.

Mitreius was not the only official connected to Roman youth organisations to strike tokens; several types exist in lead that refer to youth groups or to festivals connected to these same groups. One example is shown below: on one side is a youthful male portrait with the legend PPETRI SABI (Publius Petronius Sabinus) and on the other side is the legend MAG VIIII IVV (Magister Iuvenum VIIII - Master of the Youth, Nine) (TURS 834).

|

|

| Mitreius bronze token. | Sabinus lead token. |

That officials associated with youth organisations struck tokens in orichalcum, bronze and lead suggests that different materials might be used for tokens that were ultimately used in the same context. In this sense we should study all Roman tokens together as one class of material, rather than, as has previously been the case, separating the bronze from the lead, or the "spintriae" from other types. Clay tokens are also known from Rome, and may also ultimately provide further illumination on what, and in what contexts, these objects were used for. But these types are further evidence that some tokens were used within Roman colleges or other organisations, and may ultimately have been connected to feasts, games, celebrations or festivals.

This blog was written by Clare Rowan as part of the Token Communities Project. Thanks are due to Denise Wilding for undertaking the photography and recording of this and other tokens from the Ashmolean collection.

Bibliography:

Federico, E. and E. Miranda, eds. (1998). Capri Antica. Dalla preistoria alla fine dell'età romana. Capri, Edizioni La Conchiglia.

TURS - Rostowzew, M. (1903). Tesserarum urbis romae et suburbi. St. Petersburg.

Rostowzew, M. (1905). Römische Bleitesserae. Ein Beitrag zur Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte der römischen Kaiserzeit. Leipzig, Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

June 01, 2016

"Coins against Humanity"?

|

'Spintria' found in the Thames in 2012. PAS LON-E98F21 |

An Ancient Roman may not have been able to bring “Cards Against Humanity” to a pub game night, but they were able to bring spintriae. This particular sexy spintria was made famous when it was discovered in the Thames in 2012. There are several theories about the function of spintriae. People have suggested that they could be brothel tokens. Maybe the original owner of this token picked it up at the games? Or is it, as the title suggests, a game piece? One thing is for sure, the obverse is something that the user would remember and maybe even laugh at.

Two out of three theories are wrong. Suetonius wrote that Tiberius outlawed the use of coins stamped with the imperial image in bordellos (Clarke 1998: 244-245). This has led scholars to believe that these were brothel tokens. The idea that brothel customers would use these to pay for the services they wanted has been quickly dismissed (to see a more detailed discussion of this see Clare Rowan’s blog on this spintria).

This leads to the second theory. These tokens would be given to the public at public games. The idea this comes from a passage in Martial: “Now come sportive tokens (lasciva nomismata) in sudden showers.” (Martial Epigrams 8.78) These “sportive tokens” may be spintriae. That may seem like an odd token to give to spectators at public games celebrating things like military triumphs, but when considering the tensions in a society that placed importance on the lusts of men and the chastity of married women then maybe men receiving tokens to spend at a brothel might not be so bad (Knapp 2013: 236). However, this is not the case. The tokens would then be redeemed for gifts, but not at the local brothel. They could also provide a bit of a tough spot for an emperor who did not have the best press coverage. For example, viewers could be reminded of Tiberius’ sexual acts with boys on Capri (Suetonius Life of Tiberius 43-44). It is unlikely that an emperor, would want his people to snigger behind his back for what he got up to in his private life; thus, this theory seem implausible.

This leaves us with the third theory: these are game pieces. Although we don’t know what game these pieces were used with, we can be pretty sure that it was plenty of inspiration for the scenes of the game makers. There are other spintriae that have numbers going from I to XVI (1-16), but the sex scenes are different. This has led some scholars to believe that there is a correlation between the numbered spintriae and the illustrations of the sex manuals (Clarke 1998: 244, Clarke 2007: 194-5). This is also similar to the Pompeiian wall paintings found in the Suburban Baths. These are believed to have been numbered in a way similar to the lockers in the men’s changing room. As an added memory device, a taboo sex scene was placed above the number. The person using that space may not be able to remember his number, but they would probably be able to remember that funny dirty picture above it! (Savenga 2009).

This humour and function as a mnemonic device carried over to the game containing the spintriae. This spintria is tame compared to some of the other spintriae, so it was probably not one that was laughed too much. The steamy scene between this man and woman would have made the game memorable and may have reminded the player of what he had seen, read, heard, or even done. The fact that spintriae have been found in a widespread area, indicates that it Ancient Romans tended to have similar humour, played similar games, or that people loved this game so much that they brought it with them when travelling. Unfortunately, it may have been a male-only game. There were complaints [in Ancient Rome] that naughty pictures were corrupting respectable girls (Langlands 2006: 53). So, while the same sense of humour as a game of “Cards Against Humanity”, it might not have been a game to bring along to a game night with mixed company. However, it is not unreasonable to think that some clever minxes did manage to play “Coins Against Humanity”.

This month's blog was written by Katrina Anderson. Katrina is a Master’s student at Warwick University, who has recently become interested in the role of sex and gender in Ancient Roman art.

Bibliography

Clarke, J. (2007) Looking At Laughter. (London: University of California Press).

Clarke, J. (1998) Looking At Lovemaking. (London: University of California Press).

C. Rowan, Coins at Warwick: Ain’t talkin’ ‘bout love. Roman “Spintriae” in context.(1 Aug 2015). Accessed 10th May 2016.

Knapp, R. (2011) Invisible Romans. (London: Profile Books).

Langlands, R. (2006) Sexual Morality in Ancient Rome. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Martial, Epigrams, trans. Shackleton Bailey, D.R. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press: 1993) 2 vols. from Loeb Classical Library.

Sayenga, K. Sex in the Ancient World: Prostitution in Pompeii, Documentary, directed by Kury Sayenga (2009; New York: History).

Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, trans. J.C. Rolfe (London: William Heinemann: 1913) 1 vol. from Loeb Classical Library.

August 01, 2015

Ain't talkin' 'bout love. Roman "Spintriae" in context.

|

| Roman token, found in the Thames, PAS LON-E98F21 |

In 2012 this token was found in the Thames in London, resulting in numerous news articles about this 'brothel token'. The obverse carries the Roman numeral XIIII (14), while the reverse carries a sex scene. The couple are laying on a decorated bed or a couch, the woman laying on her front while a male straddles her.

This token is part of a broader series that carry a Roman numeral between 1 and 16 on one side, and various sex acts on the other. Another series carry Roman numerals on one side and portraits of Augustus, Tiberius or Livia on the other (see below). Buttrey analysed the dies of both series and concluded they were connected; he suggested that these objects date to the Julio-Claudian period and were perhaps gaming tokens, envisaging a possible scenario where one side played 'the imperial portraits' and the other 'the sex scenes', making the game a form of salacious gossip on the sex lives of the Roman emperors.

|

| Roman token showing Tiberius and XII within wreath. |

In reality, we know very little about these objects; their sexual scenery has created numerous forgeries, and very few archaeological contexts are known. They are often called spintriae, a label created in the modern era from a reading of Suetonius' Life of Tiberius. As part of the portrayal of Tiberius' activities on Capri, Suetonius records the presence of numerous female and male prostitutes, called spintrias (Suet. Tib. XLIII, see also Tacitus, Ann. VI.1; sphinthria or spintria referred to a male prostitute in Latin, from the Greek σφιγκτήρ, and connected to the Latin/modern word sphincter). It is this tale that inspired early collectors and scholars to label these objects spintriae, and when a hoard of tokens was found on Capri it cemented the name, though they were not called this in antiquity.

Indeed, the known find contexts of these objects suggest they had little to do with sex. Although hundreds of these specimens exist (precise numbers are difficult given the quantity of fakes in existence), only a handful of closed archaeological contexts are known. We cannot know whether the Thames example was lost in antiquity, or more recently. But one example was recently found in a tomb in Mutina; associated ceramics and other coins dates the tomb to AD 22-57, suggesting Buttrey's dating of the Julio-Claudian period is correct. Another was found during an archaeological campaign on the island of Majsan; this was pierced, suggesting it had been transformed into a piece of jewellery. Scattered other examples are reported to have been found in Caesarea Maritima, in the Garigliano in Italy, on Skegness beach (likely a modern loss) and in Germany (Stockstadt am Main, Saalburg, Nendorp-Wischenborg; these are sporadic finds). Although the information on the find places of these objects leaves much to be desired, none of these find spots are brothels, and in each example there is only one 'spintria' found. What their purpose was remains a mystery. Like many Roman tokens, much more study is required before we can fully understand these objects.

This month's coin was chosen by Clare Rowan. Clare is a research fellow at Warwick, who has recently become interested in the role tokens had in Roman society.

Coin images above reproduced courtesy of the Portable Antiquities Scheme and © The Trustees of the British Museum

Select Bibliography:

Benassi, F., N. Giordani and C. Poggi (2003). Una tessera numerale con scena erotica da un contesto funerario di Mutina. Numismatica e Antichità classiche 32: 249-273.

Buttrey, T. (1973). The spintriae as a historical source. Numismatic Chronicle 13: 52-63.

Martini, R. (1997). Tessere numerali bronzee romane nelle civiche raccolte numismatiche del comune di Milano Parte I. Annotazione Numismatische Supplemento IX: 1-28.

Mirnik, I. (1985). Nalazi novca s Majsana. VAMZ 18: 87-96.

Clare Rowan

Clare Rowan

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…