MORA! A Roman token showing a game

Bronze token from the Julio-Claudian period. On one side two boys are shown seated facing each other, a tablet on their knees, playing a game. The boy on the right has a raised right hand. At the left is a cupboard or doorway (?); MORA above. On the other side is the legend AVG within a wreath. (From Inasta Auction 34, 24 April 2010, lot 381, Cohen VIII p. 266 no. 6, variant).

This token is part of a larger series of monetiform objects which are characterised by Latin numbers on the reverse. Some examples, like that shown here, have the legend AVG (referring to the emperor, Augustus) instead of a number. This same imagery, of two boys playing a game, is also found on a token with the number 6 (VI) on the other side; another example has the number 13 (XIII) on the reverse (Paris, Bibliothèque national no. 17088). This token series carry portraits of Julio-Claudian emperors or deities, or playful scenes, including imagery of different sexual positions (a sub category of tokens called ‘spintriae’ today).

|

|

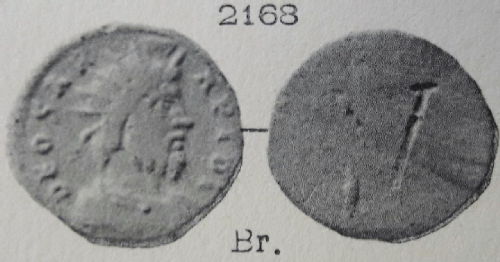

We know this token is connected to the broader series from the Julio-Claudian period because of another specimen, now in the Ashmolean museum (Ashmolean Museum, Heberden Coin Room, photo no. 10544; shown left). This token carries the same design (AVG within a wreath) as the token above, and in fact the same die was used for both tokens (called a die link).

But what of the scene on the other side? Two men or youths sit opposite each other with a gaming board between them; the figure on the right raises his hand and there is a doorway behind the figure on the left. The word MORA sits above the scene: in Latin mora meant a pause or delay; it might also be used in a more imperative sense: wait! The word moraris is found on rectangular bone pieces whose function is also unknown but are thought to be gaming pieces (tesserae lusoriae). We thus have a scene of game play involving two individuals at a moment in time when one player is being asked to pause.

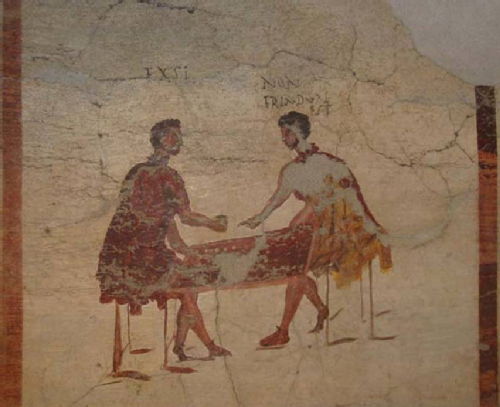

The scene is reminiscent of a painting from the bar of Salvius in Pompeii in which two men are depicted playing dice with their speech written above them - one declares 'I won' (exsi), while the other protests 'It's not three; it's two' (non tria duas est). Other paintings show the quarrel escalating, with the landlord eventually throwing the two individuals out of the bar.

|

The gaming scene on this token, as well as the numbers present on most of the tokens of this broader series, has led to the suggestion that these pieces functioned as gaming counters. However, unlike the bone gaming counters that carry numbers, these pieces have never been found together as a ‘set’, and don’t carry scratches that suggest they might have been used on a board (though this does not exclude their use in lotteries or similar). Instead it is possible that the scene was chosen because it communicates a feeling of fun. Lead tokens also carry numbers and similar scenes (including a scene of game play on a lead token said to be found in Ostia); these objects may have been used in festivals or other contexts associated with game play.

This blog entry was written by Clare Rowan as part of the Token Communities in the Ancient Mediterranean Project. It is based on a catalogue entry for a token that will feature in a forthcoming exhibition on ancient games and gaming in Lyon in June 2019, which is part of the Locus Ludi project.

Related Bibliography

Mowat, R. (1913). Inscriptions exclamatives sur les tessères et monnaies romaine. Revue Numismatique 67: 46-60.

Rodríguez Martín, F. G. (2016). Tesserae Lusoriae en Hispania. Zephryus 77: 207-20.

Rostovtsew, M. (1905). Interprétation des tessères en os avec figures, chiffres et légendes. Revue Archéologique 5: 110-24.

Clare Rowan

Clare Rowan

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…