All 4 entries tagged Provost

View all 16 entries tagged Provost on Warwick Blogs | View entries tagged Provost at Technorati | There are no images tagged Provost on this blog

November 10, 2017

World Kindness Day

Having just read this week’s issue of Insite Inbox – Warwick’s staff newsletter, I’ve been reminded that Monday 13 November is World Kindness Day. Of course, it’s easy to be sceptical about the value of the growing number of “awareness” days, and yet their existence does prompt constructive action and reflection in some quarters of our society and in my view that has to be a good thing! For me, the announcement reminded me that it was about a year ago when I wrote my blog on kindness so it seemed like a good time to revisit this theme. Looking at the web coverage of World Kindness Day, I was struck by the focus on doing good things – kindness as positive acts (giving out chocolate, flowers, helping others). And while we should never restrict such positive acts only to one day a year, it’s great to see something that encourages a proactive approach to “doing kind things”. (And for Warwick colleagues wanting to do your bit within the University - look out for Warwick Kindness cards!)

But we shouldn’t forget something that I think is equally important and that is the importance of “doing things kindly” – a way of behaving that I think can help us create a better working environment. When I blogged on this previously, I was at pains to stress that whatever we have to do in our working lives – even if it is the tough, difficult and painful decisions we may have to take – we should do so in a way that respects individuals, is supportive, constructive and compassionate.

But we shouldn’t forget something that I think is equally important and that is the importance of “doing things kindly” – a way of behaving that I think can help us create a better working environment. When I blogged on this previously, I was at pains to stress that whatever we have to do in our working lives – even if it is the tough, difficult and painful decisions we may have to take – we should do so in a way that respects individuals, is supportive, constructive and compassionate.

It’s certainly a mantra that I try to live up to. Do I always succeed? Sadly, I probably don’t and I suspect that’s because sometimes it just isn’t easy and sometimes I’m perhaps careless or rushed. But I like to think my intentions are always to act kindly. And of course therein lies a challenge for all of us – what determines whether something is “done kindly” – is it my intention when I do something or is it your experience of what I do? Now, maybe this is a question that our colleagues in Philosophy are best placed to answer, but it reminds me that if we really do want to try to create a kinder working environment we do have to try to understand both the intentions and experiences of others. And I think this is about trying to see the best in people and trusting that they mostly have good intentions; it’s also about being sensitive and aware that even the most well-intentioned acts can sometimes have unintended consequences for the person who experiences then.

So if there is a message that’s going to be uppermost in my mind for World Kindness Day, it’s probably going to be one that focuses on the way I do things and, my experiences of things that others do. And a big part of that message will be a reminder to myself always to try to act kindly, always to be willing to learn from the experiences and responses of others if I am unintentionally unkind and finally try to be tolerant of others if I think they are not being as kind as they intended to be.

June 12, 2017

Unconscious bias

We’re holding a day to Showcase Diversity at the University of Warwick on 14 June. I hope staff and students join us to play their part in celebrating and advancing our commitment to equality and diversity at Warwick.

Christine Ennew, Provost at Warwick, comments here on how our unconscious bias can impact inclusion, and how our understanding of ourselves and others can drive a willingness to discuss our diversity in a respectful way.

Last weekend, I found myself watching “The Imitation Game” – for a second time. If you haven’t seen the movie it’s a biopic of pioneering computer scientist, Alan Turing. It documents the work he did during the Second World War, breaking the Enigma code - an achievement which may have shortened the war by as much as two years. That in itself makes for a good story but it’s all framed by his sexuality and the way he was treated as a consequence – treatment that ultimately resulted in his suicide a decade later. Aside from the moral dimension of this tragedy, his early death was a massive loss for the UK in terms of the development of digital technologies.Similarly, when Dorothy Hodgkin was awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1964, the Daily Mail allegedly recognised her achievement with the headline "Oxford housewife wins Nobel prize".

The bias that Alan Turing and Dorothy Hodgkin experienced was very open and explicit bias; indeed it was embodied in the legal frameworks of the time. But we’ve moved a long way since those times. We are getting so much better at recognising and celebrating diversity. We know the moral arguments for equality and we know the economic case for diversity.

We continue to confront challenges in relation to bias; not the overt and explicit bias experienced by Dorothy Hodgkin or Alan Turing, but the unconscious bias that emerges in causal, daily actions and behaviour. It’s the bias associated with stereotyping, with rules of thumb and with all of the shortcuts that our brains make to help us cope with the intensity and complexity of our daily lives.

Along with some of my colleagues from the Warwick’s executive team, I recently joined a training session on “unconscious bias”. The session was designed not to eliminate biases, but to make us more aware of how our judgements of individuals and our behaviours may be influenced by our backgrounds, experiences and cultural environments. As well as raising awareness of our own individual and diverse biases, the training session also sought to help us to understand how our biases impact on others. Often those affected by unconscious bias are those who are in a minority and perhaps more likely to feel vulnerable because they are different. But all too often, we simply don’t know how others will react, how they will feel when they experience unconscious bias.

We are all likely to be affected by unconscious bias – because we may display it through our actions or because we experience it in our interactions with others. Because unconscious bias is an almost instinctive or automatic reaction, it can be difficult to eliminate. But we can mitigate its impact – through our awareness and understanding of ourselves, through our attempts to understand the experiences and feelings of others and through a willingness to discuss in a respectful way.

I hope colleagues and students at Warwick join us at our day to Showcase Diversity on 14 June.

November 08, 2016

Kindness as a Strength

For much of my academic life, I have been based in a Business School, so I’m familiar with the many fads and fashions of popular management writing. Much of this is transient, some has a basis in systematic academic research but often the greatest impact seems to come from the careful presentation of anecdotal evidence. So it would be easy to dismiss some of the popular writing around more compassionate approaches to management, concepts of servant leadership and notions of kindness within organisations. But my own experience suggests that such a sweeping judgement would also be an unwise one.

Without under-estimating the importance of a work-life balance, we should recognise that most of us spend a large part of our life at work. Who we work for and what we do usually makes a significant contribution to our identity and our sense of self. And our experience in the workplace will have a real impact on our broader well-being. Leaders and managers play a key role in defining that workplace experience but we all contribute through our behaviours and our interactions. So, as we look forward to marking our “Respect at Warwick” day on 16th November, I wanted to reflect on the importance of kindness in organisations.

A typical definition of kindness (courtesy of the Oxford English Dictionary) is “the quality of being friendly, generous, and considerate”. Treating others with kindness and being treated with kindness during out working lives feels like a very reasonable expectation. And yet, all too often it doesn’t happen. Sometimes we just don’t think or reflect on how our behaviour impacts on others, sometimes we’re just too focused on ourselves and sometimes we worry that kindness in the workplace may not be a desirable quality – especially for a manager or a leader! That may reflect a significant mis-understanding. Kindness is not weakness; concern for the well-being of others is not weakness. Kind people can still be analytical and focused; kind people are perfectly capable of exercising tight control; kind people can still take difficult decisions. They simply do so in a way that respects individuals, is supportive, constructive and compassionate.

I’ve always been keen to avoid creating stereotypes around management and leadership - there is no single right type of leader of manager – we’re all different and we all have our unique qualities. But one thing I am convinced of is that for all of us there is a real benefit from exercising kindness in the workplace. Individually we’ll feel better, happier, engaged and more highly motivated. And when that happens, we’re likely to perform better – individually and collectively.

Listening to the radio is one of my great pleasures and early one morning a few years ago I woke to a programme which referenced a quote from Kurt Vonnegut. It’s a quote that has stuck with me. And it’s perfect as my closing thought for this blog:

"Hello, babies. Welcome to Earth. It's hot in the summer and cold in the winter. It's round and wet and crowded. At the outside, babies, you've got about a hundred years here. There's only one rule that I know of, babies—God damn it, you've got to be kind."

(From God Bless You, Mr Rosewater)

Christine Ennew, Provost

September 23, 2016

Measuring the gap

I’m really proud to be working for Warwick and that makes me a bit competitive – and the idea that we are “second worst” for something is always going to catch my eye and cause anxiety. And the whole area of diversity and inclusion is something that I have worked on for a long time, so the recent headline about the gender pay gap in our independent student newspaper, “The Boar” immediately got me worried.

The issue of gender-based differences in pay in the UK has moved on a lot since the strike by women machinists at the Ford Motor Company triggered the introduction of the Equal Pay Act in 1970 (immortalised in the movie – Made in Dagenham). Although subsequently repealed, the main provisions of the Act were retained in the 2010 Equality Act.Despite legislation and a whole raft of initiatives, there continue to be significant disparities in pay by gender (and a range of other “Protected Characteristics”).

The factors behind gender pay gaps are hugely complex which makes it hard to look at this issue from a generalist perspective - factors such as differences in education, qualifications and experience to name a few. But there is evidence of the persistence of both implicit and explicit discrimination. Labour market segmentation (more women in lower paid occupations) is one such example of indirect discrimination and a recent study by Warwick academics (using Australian data) provided evidence of direct discrimination in the form of systematically lower probabilities of women successfully requesting pay rises.

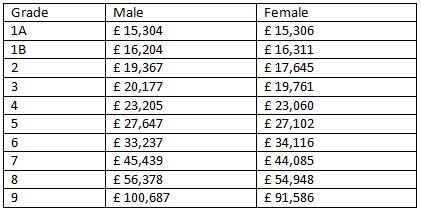

One of my roles at Warwick is the Chair of the University’s Equality and Diversity Committee, and this gave me another driver to look more closely at the UCU findings and assess them in relation to institutional practice. The Boar story claims a significant average pay gap of 18.7%. The SU says it’s very disappointed, the University says that these figures overstate the case. So let’s have a look at some figures from the University’s salary database.

I'm not saying that there is not a problem and we don’t need to address this issue but with any statistics, it is worth digging further to give context. The differences in pay between males and females are statistically insignificant in all grades except 2 and 9 (the latter being Professors, very senior Administrative and commercial staff) and small differences in either direction are primarily driven by differences in length of service. At Grade 2, the difference is entirely explained by contractual overtime paid to two groups of staff where male staff outnumber females.

At the most senior level, Grade 9, the pay gap has fallen in recent years, in part because of a rigorous programme of equality adjustment each year following the Senior Pay review (something which other institutions are also doing – including King’s and Essex). The academic pay gap at level 9 has now been corrected in two faculties and is very marginal in a third.

So why the difference between the UCU perspective and that of the University? Well, the UCU report appears to work from average figures across all grades while the figures above are disaggregated by grade. And the data above come from the University directly and is the most recent data available, while the UCU report appears to use older figures reported to the Higher Education Statistics Agency.

Putting these different data sets to one side and looking ahead, we must continue to monitor pay differentials and address any differences related to any of the protected characteristics – and not just gender. We have a high level snapshot of the current position but further, more detailed analysis would be of real value and this is something we will include on the workplan for the Equality and Diversity Committee for the coming year, alongside the commitments expressed in the “Gender Statement of Intent”.

Execblog Resource

Execblog Resource

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…