All 7 entries tagged Development

View all 71 entries tagged Development on Warwick Blogs | View entries tagged Development at Technorati | There are no images tagged Development on this blog

December 05, 2023

Encounters, dialogues and solutions for natural resource management and sustainable development

“L'homme n'est pas le maître de la terre, mais la terre est le maître de l'homme”: Encounters, dialogues and solutions for natural resource management and sustainable development in Côte d’Ivoire.

A view of the Voluntary Natural Reserve(May 2023, Photo Credit, Adou Djané)

Written by:

Adou Djané, Briony Jones, Mouzayian Khalil-Babatunde, Sita Akoko Kondo, Dohouan Village Secretary, Dohouan Forest Guides, and Dohouan Women’s Association.

The current ambitious Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) framework requires actors to work together to realize sustainable development for all. However, we continue to see the dominance of top-down development despite the fact that local communities are vital for successful and legitimate development interventions. In this blog we present one particular local community action which is part of a joint project on natural resource management in Côte d’Ivoire. Our project “L'homme n'est pas le maître de la terre, mais la terre est le maître de l'homme”: Encounters, dialogues and solutions for natural resource management and sustainable development in Côte d’Ivoire is funded by the University of Warwick as part of an International Partnership Fund and is a collaboration between the Centre Suisse de Recherche Scientifique en Côte d’Ivoire (CSRS) and the University of Warwick. It is also a collaboration with local communities working to manage their natural resources, and it is for this reason that the blog is co-authored by the project partners as well as the local communities interviewed in the framework of this project. What this blog describes is an example of an effective constellation of collaborations for activism to protect a primary rainforest on the border between Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana.

In May 2023 we gathered in the village of Dohouan, in the South-East of Côte d’Ivoire and close to the border with Ghana. It is here that the Tanoe-Ehy Forest is situated, one of the last areas of rainforest in the country, home to three of the most endangered primates in the region, and under threat from conversion to palm oil plantations. We spoke together about the successful block in the expansion of palm oil plantation, and the designation of the forest as a Voluntary Natural Reserve by the Government of Côte d’Ivoire. Two themes are clear in the conversations that we had: (1) for the importance of future generations being able to see, enjoy, and use the forest; and (2) the importance of collaborative action combining local, regional and national actors.

Meeting with the community representatives (May 2023, Photo Credit, Adou Djané)

“Tous, on est impliqué”

These words of the Village Secretary: “We are all responsible” sum up the successful action to block the palm oil plantation expansion into Tanoe-Ehy Forest.

In the 1980s and 1990s, structural adjustment policies, advised by international financial institutions, were implemented in Côte d’Ivoire. This included the privatisation of the previously state-owned Palm industries in 1997. The assets of the company were bought by three private enterprises, significantly reducing the land ownership of smallholders in palm oil producing areas.

The forest is a valuable resource not only for the palm oil companies but for the local communities. There is a daily pleasure in seeing the forest, knowing the names of plants and animals, and being able to use the resources of the forest. This includes plants for medicine, wood for construction of buildings, and the use of flora and fauna in important cultural ceremonies. Successfully saying ‘no’ to the palm oil plantation in the rainforest adjacent to Dohouan is an important example of local community activism in the context of contested management of natural resources.

“Que la fôret demeure fôret”

When asked about key priorities, a group of village representatives told us that first and foremost they wished “the forest to be a forest”.

Supported by a network of voluntary forest guides, the rainforest is protected, and its use managed. The forest guides take great pleasure in the voluntary nature of their work, both directly preserving the forest through patrols and indirectly through educating the local population about the importance of sustainable management of the forest. There are now limits as to how much wood can be used from the forest, which plants can be taken out, a ban on hunting, and limitations placed on fishing.

Before the forest was designated a Voluntary Natural Reserve the local communities in the area participated in workshops to help to decide and define regulations for its management and protection. Representatives of the Government were present to advise on the different options available, but it was the local population who agreed together to request a Voluntary Natural Reserve.

“Je le fait pas pour moi, mais pour les générations de l’avenir”

The fight to save the forest is framed by local residents as a commitment to future generations, as this quote from the forest guides illustrates: “I am doing it not for me, but for future generations”. However, this was not simply a question of local community versus oil plantation company, it was a sustained effort over time through a network of collaborations and associations spanning different levels of governance.

The CSRS first began working with the local communities in the area in 2006, supporting activities around education to counter some depleting local practices while at the same time preserving the forest and its role in community life and sustenance. This initiative by CSRS “captured their attention” and it was then that “the idea of conservation was born”, according to the President of the Fishermen’s Association. It was the CSRS who accompanied local associations on visits to the relevant government ministries, provided information about the rights of the local communities, and supported the workshops which evolved and manifested in the request for classification of the forest as a voluntary natural reserve.

The outcome was a victory for the forest, it is protected and preserved. But it is still an ongoing journey of negotiation between different actors. The forest crosses the border with Ghana, and lack of adequate coordination, partly due to will and partly due to resources, undermine what should be a shared conservation effort. Lack of resources also undermine the work of the forest guides who do not have access to basic equipment such as walkie talkies or permanent patrol posts which would allow them to do their work in the remote setting of the forest.

“L’union fait la force”

These words, spoken by the President of the Fishermen’s Association: “together we’re stronger”, certainly seems a foundation for the past, present and planned activities of conserving the forest.

But this union has cracks, not least a feeling that since the official designation of the forest as a voluntary natural reserve, that the state has washed its hands of supporting in its management. Tensions between Ghanaian and Ivoirian Forest patrols as well as between Ghanaian and Ivoirian fishermen require time and resources to manage sensitively and fairly.

Resources

Recherches et Actions pour la Sauvegarde des Primates en Côte d’Ivoire CI (RASAPCI)

Où sont les colobes rouges de Miss Waldron?, Nature et Environnement

Authors’ Bio

This blog is written collaboratively by researchers in the Centre Suisse de Recherche Scientifique en Côte d’Ivoire (CSRS), the Department of Politics and International Studies University of Warwick, and representatives of the village of Dohouan in the South-East of Côte d’Ivoire by the border with Ghana. The blog is an output of our research project“L'homme n'est pas le maître de la terre, mais la terre est le maître de l'homme”: Encounters, dialogues and solutions for natural resource management and sustainable development in Côte d’Ivoire, funded by the University of Warwick as part of an International Partnership Fund (2022-2024).

October 09, 2023

Conflicting Narratives on Development and Environment in Argentina

Source: Photo credits ‘no-al-litio’: Ramiro Barreiro, Latfem.org

Conflicting Narratives on Development and Environment in Argentina. What can we learn from lithium exploitation in Argentina?

Written by Mariana Paterlini

Argentina is an unequal country where the gap between the rich and the poor keeps widening, while its economy still depends on large-scale agriculture for export. However, since the 90s, and influenced by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, mining has emerged as a potential source of economic growth. Furthermore, in the last ten years, the Northwest region has gained visibility as part of the "lithium triangle". Along with Bolivia and Chile, this area concentrates 85% of the world's reserves of this crucial metal for the energy transition. Simultaneously, the consolidation of different actors questioning the benefits and negative impacts of the dominant development model has increased over the last twenty years, giving rise to a national scenario populated by environmental conflicts.

Lithium is often presented as a critical mineral in the transition to renewable energy. Currently, governments in the North promote its exploration and, in line with their international environmental commitments, link it to sustainable mining contributing to decarbonisation. Thus, it reproduces a Modernity discourse that conceives the environment and its resources as commodities ready to serve the human economic organisation. However, its extraction implies intensive water use that alters soil conditions and negatively impacts the ecosystem, thus an exploitation of the environment. Furthermore, this practice often violates the rights of local communities. Specifically, indigenous peoples who have remained marginalised since colonial times.

This research, conducted as the dissertation to finish an International Development MA at the University of Warwick, examined cultural products related to lithium exploitation circulating in national media, guided by a transdisciplinary theoretical framework that merges postcolonial development studies, political ecology, and sociology of culture, through discourse analysis. This approach made it possible to engage with how diverse actors conceptualise their relationships with the environment differently and consider Argentina's position in relation to the current centres of economic power. Then, five development narratives were identified while observing the relation of each model with the environment, the reproduction of colonialism each one entails and their efforts towards an ideal of emancipation for the country.

Here culture is thought of as a historical process anchored in common sense, habits, and beliefs which materialise the social relations of inequality between different groups involved. Therefore, exploring the cultural dynamics in the case of lithium exploitation makes it possible to decentre the hegemonic development narrative and expand the political imagination presenting alternative possibilities at stake.

The five development narratives identified through this exercise -orthodox extractivism, extractivism with industrialisation, green new deal (GND), degrowth, and community autonomism-shape heterogeneous ways of materialising human relations with nature. Moreover, they entail fields of possibilities and practices with which different groups can identify and between which relations of opposition or articulation are established, considering the power disputes across them. Therefore, based on the frequency of circulation, the actors legitimising the narratives and the media outlet in which they circulate, orthodox extractivism and extractivism with industrialisation are residual narratives, GND is the dominant one, and degrowth and community autonomism are the emergent.

Regarding the environment, whereas residual models assimilate it as natural resources intended to be exploited intensively (lithium appears as a commodity that brings in foreign currency, referred to as the "new oil", "white gold", or a "hidden treasure", allowing local communities to leave their "primitive" original state), the dominant model frames this exploitation within environmental standards that remain unclear (lithium appears as key for an energy transition, and refer as part of a "sustainable mining" linked to accountability and efficiency). In contrast, the emergent narratives understand the environment as the co-creation of a relationship between the biophysical and its inhabitants, entailing caring relationships (indigenous peoples expose how their identities and culture disappear if their ecosystem dies). Connected to this arises the question of its management. While the residual and the dominant narratives discuss it in terms of strategic resources that provincial or national governments may administer, the emerging models stress recognising the legitimate participation of indigenous communities and organised civil society in the debate.

Regarding emancipation, orthodox extractivism is the only narrative that does not envision emancipation and reproduces colonial relations between the North and the South, assimilating development to economic growth. On the other hand, extractivism with industrialisation, GND, degrowth and community autonomism include an emancipatory aspect. Nonetheless, their understanding of emancipation differs; the two former links it to improving Argentina's position in the global market, neglecting power inequalities within the country, and understanding economic growth as the basis of development. The latter consider emancipation from a bottom-up perspective, undervaluing economic growth as the basis of development and connecting it to a shift in the relationship with the environment.

Finally, in the residual and dominant narratives, it is possible to trace persistence of the Modernity discourse with nuances, reproducing the marginalisation of local communities and focusing on the country's position within global dynamics. In this way, they neglect the differentiated impact these dynamics have in different sectors, particularly the negative consequences on already marginalised communities. On the other hand, the emergent models openly challenge this discourse, emphasising the reinforcement of local aspects to reverse the undesired effects of the current global ones.

This study showed that although emergent narratives usually appear on critical and alternative media outlets, they circulate in mainstream media to a lesser extent. Therefore, it made it possible to think that new futures, engaged with alternative development models, can be shaped by the massification of some unusual alliances already occurring in this arena. Thus, it might be relevant to delve deeper into the strategies for consolidating these unusual alliances while generating evidence to identify whether they effectively contribute to counteracting the reproduction of inequality.

Whilst the hegemonic development discourse aims to improve Argentina's position in the global system, it reproduces mechanisms that exacerbate the differentiated impact of this development model on different sectors of the population, producing environmental damages and more inequality. This analysis sought to deepen understanding of this situation and demonstrate alternative ways forward. The final goal remains on the side of hope and advocates for the plural construction of a development model intersected by the values of social justice, in which the motto of the Sustainable Development Goals becomes a reality: leaving no one behind.

Author Bio

Mariana Paterlini has recently graduated with an MA in International Development at the University of Warwick. She is a human rights activist whose practice has focused on feminism, gender rights, economic, social, and cultural rights and, more recently, the right to the future. Her master's dissertation addressed continuities and ruptures traceable in the narratives circulating in the public debate on development and the environment in Argentina. She was a Chevening scholar, and this piece was made possible by funding from the Chevening Scholarships, the UK government's global scholarship programme, funded by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO).

August 17, 2022

The KazAID Story

The KazAID Story

Written by: Prachi Agarwal

The ongoing Russian aggression in Ukraine has captured the world’s attention. Conversations focusing on the fragility of countries’ sovereignty and security are growing, especially among former soviet republics. Despite threats to sovereignty and security, Kazakhstan, the largest country in central Asia and a former member of the USSR, aspires to be a global superpower. However, the primary challenge to this aspiration lies in ‘promoting increased connectivity while maintaining a freedom of action’. The solution to this challenge may require using foreign aid as an instrument of foreign policy.

Thus, the primary aim of this blog is to describe and highlight pertinent issues for Kazakhstan’s foreign aid practices in the context of using foreign aid. The rationale behind such an endeavour is that KazAID (Kazakhstan’s foreign aid body) remains an under-researched area. KazAID’s establishment was driven by fulfilling Kazakhstan’s security needs and economic aspirations. While the role of foreign aid as a foreign policy instrument of the rich countries may be widely known, KazAID’s story shows that other developing nations could also challenge the existing western hegemony through strategic aid foreign practices.

Contextualising Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan has been carefully trying to maintain relations with its largest trading partners - Russia, the United States and China. Kazakhstan believes that Eurasian connectivity could benefit its economic and security interests. Simultaneously, Kazakhstan maintains close ties with Russia and China. Earlier in 2022, when protests broke out against the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Kazakhstan sought assistance from Russia to quell the growing protests. These protests were guided by the fear that Kazakhstan, too, may be invaded by Russia. These fears are not misguided as being a member of Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union (EaEU) is getting increasingly costly for Kazakhstan. Critics suggest that while the EaEU mimics the EU’s institutional framework, in practice it is an agency for Russia’s geopolitical interests. Being a member of the EaEU constrains Kazakhstan’s sovereignty and weakens its economy and it may want to leave the EaEu, thus inviting Putin’s wrath. China, too, pursues economic interests in Kazakhstan as its largest trading partner and an emerging source of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). Such close ties with China and Russia may invite sanctions from the West. Therefore, Kazakhstan maintains a multivectoral foreign policy and foreign aid is a crucial, yet overlooked, aspect Kazakhstan’s foreign policy.

From Aid Recipient to Aid Donor

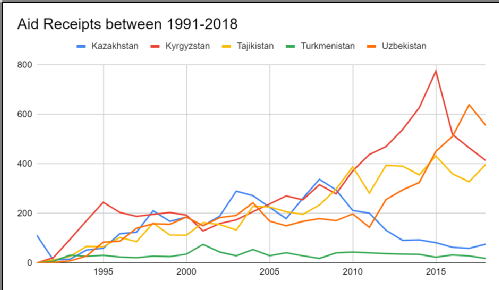

Kazakhstan delivers foreign aid through its agency, KazAID. However, Kazakhstan used to be a prominent aid recipient rather than a donor. Previously, Kazakhstan received aid under the OECD’s Official Development Assistance (ODA) banner. Figure 1 captures the trends in aid receipt amongst the Central Asian countries to show that until 2007, Kazakhstan received aid in the same proportion as most countries in the region, but post 2007, the amount of aid received drastically decreased. Simultaneously, the demand for aid among other countries in the region (barring Turkmenistan) continued to increase.

Figure 1: Trends in Aid Receipts (Source: Author’s Own; Data: QWIDS)

Some argue that this pivot may be due to the oil industry. In figure 1, the increasing trend (till 2007) occurred as Kazakhstan (and other Central Asian countries) needed assistance in transitioning to a market-based economy post their disintegration from the USSR. Simultaneously, due to its export policies for Uranium, wheat, and other natural resources, Kazakhstan experienced massive increases in its GDP.

In 1999, former President Nazarbayev had announced the intentions to reduce aid dependency. Following this decision, Kazakhstan took measured steps in reducing its loans and grants. Due to the increases in national income, the World Bank, in 2006, categorised Kazakhstan as an upper-middle-income country. Subsequently, in line with its foreign policy, Kazakhstan aspired to be included in the elite Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Becoming a donor nation was critical in achieving this aspiration. In 2014, the government implemented the ODA Law which established the tasks, agendas, regulations and organisational matters for the same. This law served as the legal basis for establishing Kaz AID

What is KazAID?

KazAID was established through a presidential decree, under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Kazakhstan. It was founded with the aim of building regional cooperation, helping Kazakhstan integrate into regional systems, connecting Europe and Asia, and promoting peace and security in the region. Thus far, major chunks of its aid have been delivered to countries in the region, but KazAID intends to extend aid to Latin American and African countries, too.

With a unilateral aid of USD 2 million, Afghanistan has been KazAID’s largest aid recipient so far. KazAID also supplies aid to Tajikistan. Although Tajikistan didn’t list Kazakhstan as a ‘foreign donor’ in one of its reports, KazAID continued with its initiatives in the region to build ‘brotherly relations’. Such activities resulted in an invitation from the OECD for a conference in Paris in 2018. Subsequently, Kazakhstan’s international image improved considerably, even perhaps establishing Kazakhstan as a regional leader. However, countries in the region are still reluctant to accept this status.

Figure 2 shows the amount of developmental assistance provided as a share of Kazakhstan’s Gross National Income (GNI) to indicate that initially, the aid amounts increased exponentially and then stabilised as it received the OECD Paris Conference invite. This further alludes to Kazakhstan’s strategy of employing foreign aid to aid its own agendas.

Figure 2: Developmental Assistance provided as a share of GNI (Source: OECD, 2020)

At a conference, the Kazakh Ministry of Foreign Affairs expressed that KazAID is an essential tool for the region’s long-term growth and development which would ensure peace and stability in the region. Indeed, this would directly benefit Kazakhstan’s own security and economic interests, which highlights the importance of foreign aid in Kazakhstan’s multivectoral foreign policy.

Situating KazAID in Kazakhstan’s Foreign Policy & Identity as a Donor

Given Kazakhstan’s proximity, history and economic ties with Russia, Kazakhstan could have invited sanctions from the United States or the NATO countries. However, to avoid this, Kazakhstan has employed its aid agency to partner with the US, the UN and other important nations/ organisations. Through KazAID initiatives and ODA policies, Kazakhstan’s donor identity was built which reaffirmed its authority in the region. But, in doing so, Kazakhstan has contrasted itself against other emerging donors.

Kazakhstan uses a ‘hybrid identity’ as a donor to combine aspects of being a traditional and an emerging donor. Historically, Kazakhstan has always maintained partnership, self-reliance and non-interference in other nations’ internal affairs. This is significantly different from the practices of traditional aid agencies, such as USAID. Yet, the motivations of establishing an aid agency and practices match that of the traditional aid agencies, contrasting it from other emerging donors.

For a landlocked and transcontinental country, like Kazakhstan, the development of foreign policy is crucial. However, to effectively employ the landlocked location, Kazakhstan must diversify its foreign policy approaches to develop its foreign aid practices. To this end, Kazakhstan strategically engages in foreign aid practices to cushion itself from hostile nations while ensuring a dominant role in the region. Thereby presenting itself as a viable ally to Russia rather than a threat, despite maintaining relations with the US.

Author bio:

Prachi Agarwal is an independent researcher and development sector professional, based out of India. Her academic interests include, among others, understanding foreign aid in relation to power and hegemony in a global setting.

Mouzayian Khalil

Mouzayian Khalil

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…