All 2 entries tagged Foreign Policy

View all 6 entries tagged Foreign Policy on Warwick Blogs | View entries tagged Foreign Policy at Technorati | There are no images tagged Foreign Policy on this blog

August 17, 2022

The KazAID Story

The KazAID Story

Written by: Prachi Agarwal

The ongoing Russian aggression in Ukraine has captured the world’s attention. Conversations focusing on the fragility of countries’ sovereignty and security are growing, especially among former soviet republics. Despite threats to sovereignty and security, Kazakhstan, the largest country in central Asia and a former member of the USSR, aspires to be a global superpower. However, the primary challenge to this aspiration lies in ‘promoting increased connectivity while maintaining a freedom of action’. The solution to this challenge may require using foreign aid as an instrument of foreign policy.

Thus, the primary aim of this blog is to describe and highlight pertinent issues for Kazakhstan’s foreign aid practices in the context of using foreign aid. The rationale behind such an endeavour is that KazAID (Kazakhstan’s foreign aid body) remains an under-researched area. KazAID’s establishment was driven by fulfilling Kazakhstan’s security needs and economic aspirations. While the role of foreign aid as a foreign policy instrument of the rich countries may be widely known, KazAID’s story shows that other developing nations could also challenge the existing western hegemony through strategic aid foreign practices.

Contextualising Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan has been carefully trying to maintain relations with its largest trading partners - Russia, the United States and China. Kazakhstan believes that Eurasian connectivity could benefit its economic and security interests. Simultaneously, Kazakhstan maintains close ties with Russia and China. Earlier in 2022, when protests broke out against the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Kazakhstan sought assistance from Russia to quell the growing protests. These protests were guided by the fear that Kazakhstan, too, may be invaded by Russia. These fears are not misguided as being a member of Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union (EaEU) is getting increasingly costly for Kazakhstan. Critics suggest that while the EaEU mimics the EU’s institutional framework, in practice it is an agency for Russia’s geopolitical interests. Being a member of the EaEU constrains Kazakhstan’s sovereignty and weakens its economy and it may want to leave the EaEu, thus inviting Putin’s wrath. China, too, pursues economic interests in Kazakhstan as its largest trading partner and an emerging source of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). Such close ties with China and Russia may invite sanctions from the West. Therefore, Kazakhstan maintains a multivectoral foreign policy and foreign aid is a crucial, yet overlooked, aspect Kazakhstan’s foreign policy.

From Aid Recipient to Aid Donor

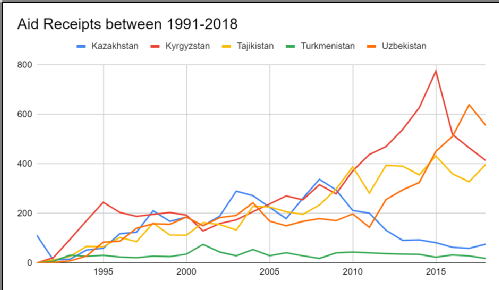

Kazakhstan delivers foreign aid through its agency, KazAID. However, Kazakhstan used to be a prominent aid recipient rather than a donor. Previously, Kazakhstan received aid under the OECD’s Official Development Assistance (ODA) banner. Figure 1 captures the trends in aid receipt amongst the Central Asian countries to show that until 2007, Kazakhstan received aid in the same proportion as most countries in the region, but post 2007, the amount of aid received drastically decreased. Simultaneously, the demand for aid among other countries in the region (barring Turkmenistan) continued to increase.

Figure 1: Trends in Aid Receipts (Source: Author’s Own; Data: QWIDS)

Some argue that this pivot may be due to the oil industry. In figure 1, the increasing trend (till 2007) occurred as Kazakhstan (and other Central Asian countries) needed assistance in transitioning to a market-based economy post their disintegration from the USSR. Simultaneously, due to its export policies for Uranium, wheat, and other natural resources, Kazakhstan experienced massive increases in its GDP.

In 1999, former President Nazarbayev had announced the intentions to reduce aid dependency. Following this decision, Kazakhstan took measured steps in reducing its loans and grants. Due to the increases in national income, the World Bank, in 2006, categorised Kazakhstan as an upper-middle-income country. Subsequently, in line with its foreign policy, Kazakhstan aspired to be included in the elite Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Becoming a donor nation was critical in achieving this aspiration. In 2014, the government implemented the ODA Law which established the tasks, agendas, regulations and organisational matters for the same. This law served as the legal basis for establishing Kaz AID

What is KazAID?

KazAID was established through a presidential decree, under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Kazakhstan. It was founded with the aim of building regional cooperation, helping Kazakhstan integrate into regional systems, connecting Europe and Asia, and promoting peace and security in the region. Thus far, major chunks of its aid have been delivered to countries in the region, but KazAID intends to extend aid to Latin American and African countries, too.

With a unilateral aid of USD 2 million, Afghanistan has been KazAID’s largest aid recipient so far. KazAID also supplies aid to Tajikistan. Although Tajikistan didn’t list Kazakhstan as a ‘foreign donor’ in one of its reports, KazAID continued with its initiatives in the region to build ‘brotherly relations’. Such activities resulted in an invitation from the OECD for a conference in Paris in 2018. Subsequently, Kazakhstan’s international image improved considerably, even perhaps establishing Kazakhstan as a regional leader. However, countries in the region are still reluctant to accept this status.

Figure 2 shows the amount of developmental assistance provided as a share of Kazakhstan’s Gross National Income (GNI) to indicate that initially, the aid amounts increased exponentially and then stabilised as it received the OECD Paris Conference invite. This further alludes to Kazakhstan’s strategy of employing foreign aid to aid its own agendas.

Figure 2: Developmental Assistance provided as a share of GNI (Source: OECD, 2020)

At a conference, the Kazakh Ministry of Foreign Affairs expressed that KazAID is an essential tool for the region’s long-term growth and development which would ensure peace and stability in the region. Indeed, this would directly benefit Kazakhstan’s own security and economic interests, which highlights the importance of foreign aid in Kazakhstan’s multivectoral foreign policy.

Situating KazAID in Kazakhstan’s Foreign Policy & Identity as a Donor

Given Kazakhstan’s proximity, history and economic ties with Russia, Kazakhstan could have invited sanctions from the United States or the NATO countries. However, to avoid this, Kazakhstan has employed its aid agency to partner with the US, the UN and other important nations/ organisations. Through KazAID initiatives and ODA policies, Kazakhstan’s donor identity was built which reaffirmed its authority in the region. But, in doing so, Kazakhstan has contrasted itself against other emerging donors.

Kazakhstan uses a ‘hybrid identity’ as a donor to combine aspects of being a traditional and an emerging donor. Historically, Kazakhstan has always maintained partnership, self-reliance and non-interference in other nations’ internal affairs. This is significantly different from the practices of traditional aid agencies, such as USAID. Yet, the motivations of establishing an aid agency and practices match that of the traditional aid agencies, contrasting it from other emerging donors.

For a landlocked and transcontinental country, like Kazakhstan, the development of foreign policy is crucial. However, to effectively employ the landlocked location, Kazakhstan must diversify its foreign policy approaches to develop its foreign aid practices. To this end, Kazakhstan strategically engages in foreign aid practices to cushion itself from hostile nations while ensuring a dominant role in the region. Thereby presenting itself as a viable ally to Russia rather than a threat, despite maintaining relations with the US.

Author bio:

Prachi Agarwal is an independent researcher and development sector professional, based out of India. Her academic interests include, among others, understanding foreign aid in relation to power and hegemony in a global setting.

September 14, 2021

‘Brand Modi’ and India's Policy Concerns

Photo by Kremlin.ru; licensed under CC BY 4.0

As India was struggling with its devastating second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, help poured in from expected and unexpected corners of the world. For the first time in 16 years, India began accepting assistance not only from its friendly strategic partners like the US and Russia but also from its fiercest economic and geopolitical competitor, China. However, India has been reluctant to acknowledge the help provided as “aid”. Instead, India’s External Affairs Minister, S Jaishankar, has referred to it as “friendship and support” and as a favour returned for the earlier COVID-19 assistance India provided the world. Even as its socio-economic, public health, democratic freedom and other indicators continue to plummet, India wants to be seen as an equal partner, not in need of aid but rather only “support”. As India resumed trade talks with the UK, EU and others, it continued its wordplay by emphasising the ideal of Vasudhaiva kutumbakam (“the world is one family”) as Modi’s catchphrase Atmanirbhar Bharat ("self-sufficient India") conveniently took a backseat. Such moves reveal India’s excessive preoccupation with maintaining its image both domestically and internationally. What is troubling though is that this posture within India’s ruling elite has also led to the mismanagement of covid crises. The state risked the lives of many by allowing mass religious and political gatherings, irrational vaccination policies, undercounting and underreporting of covid cases and the like. This post delves into why the Modi government is engaging in semantic manipulations to protect its image and how such manipulations harm India.

One possible reason for the BJP bending over backwards with its wordplay is to defend its “Vaccine Maitri” initiative. The initiative, which provided vaccines to countries of the global south, met with immense criticism as India faced vaccine shortages amid its devastating second wave. Two months after the initiative was launched, the government proudly proclaimed in the parliament that more shots were sent out of the country than were administered to its citizens. Thus, as the government was being condemned, framing the aid as a favour returned was essential for party interests, especially as state election campaigns were underway. The government needed to vindicate itself by arguing that the aid it provided was a beneficial foreign policy investment for India.

However, such a defence of vaccine maitri needs to be viewed from the broader BJP agenda of protecting “Brand Modi”. Since the 2014 national elections in India, Hindutva realism has become a mainstay of the BJP’s playbook. The BJP emphasises a strong centralised leadership and a doctrine of self-help or self-reliance. Modi has become the face of BJP’s Hindutva realism. The 2016 demonetisation of Indian currency, the surgical strikes across the Line of Control, abrogation of special status to India’s only Muslim majority state, imposition of a nationwide lockdown with only a few hours’ notice, and Atmanirbhar Bharat are only some projects the government undertook to portray Modi as a fearless leader working for India’s integrity and sovereignty. Even the recent cabinet reshuffle, which saw some of BJP’s top-leadership lose portfolios, was not shown as the government’s acceptance of its failures but rather portrayed Modi as a dynamic Prime Minister, who could punish his own ministers for poor performances. Despite running a heavily centralised administration, where every major policy decision requires his approval, Modi is seen shifting the blame onto his aides.

The BJP government was also pressured into paronomasia due to its obsession with building its brand. As Modi began to depict himself and India as a strong and rising power, Indians in India and abroad began to feel emboldened and prematurely succumbed to the vision of India as a vishwaguru (“ a teacher to the world”). Thus, as India, in a matter of days, was reduced to an aid recipient from its cultivated image of an aid donor, Indians and the Indian diaspora were embarrassed. They were ashamed and resented that the country was brought to its knees. Therefore, in a move to prevent its supporters from feeling disaffected, the BJP began terming the aid received as “friendship”.

The cost of BJP’s rhetoric has been high for India. Firstly, by denying and downplaying the crisis, the Indian political elite had allowed itself to be blindsided in its handling of the crisis. In January this year, instead of preparing for the second wave by ramping up testing and vaccine production, Modi was busy claiming to the world during the 2021 WEF summit that he had crushed the COVID pandemic. As the state can’t fix what it doesn’t recognise as a crisis, India underwent critical failures in governance and administration. Modi proclaiming his victory over the pandemic in both the international and domestic arena also made matters worse as it infused irrational confidence among Indians. Ordinary citizens and political leaders alike, taking Modi’s claims for granted, threw caution to the wind and began attending gatherings in hoards. Millions worshipped their gods at the Kumbh Mela, and their leaders in political rallies with no social distancing or masks putting lives at risk.

Modi’s BJP did not only fail to prevent a crisis, but it failed to mitigate one when it inevitably arrived. The government’s ministries surrendered national interest, democratic freedoms and civil liberties to protect the regime’s interest. As the living begged for oxygen and the dead for a space to lay their bodies, the Government showed little concern for its citizens. It hid its cases and resorted to draconian laws to suppress criticism. The External Affairs Minister also called on his diplomats to counter the apparently “one-sided” criticism of the government by international media. To make matters worse, BJP indulged in medical humbuggery. Vijay Chauthaiwale, the head of the national party's foreign affairs department, encouraged the consumption of bovine urine and turmeric as possible cures. Furthermore, reacting to the criticism over the Kumbh Mela, the Uttarakhand chief minister declared on March 20, “nobody will be stopped in the name of COVID-19 as we are sure the faith in God will overcome the fear of the virus.” National and Global networks need credible data to assess damages and determine disease dynamics and such actions by the government only make policymaking weaker and more difficult. As The Washington Post's aphorism goes, “democracy dies in darkness”.

In the realm of foreign policy, India’s failures have only played to China’s advantage. Not only have China’s doors to South Asia been left unguarded, but Modi’s obsession with image building and photo-ops has made him a liability in dealing with China. Modi had become tone-deaf to Chinese aggression as Xi Jinping met him at least 18 times since 2014 to give him the photo-ops he wanted. This only led to BJP making extremely bold statements such as their intention to take back Aksai Chin from China rather than be vigilant of Chinese transgressions at Eastern Ladakh last year. Instead of taking action, the government was busy denying Chinese occupation. This only let China take control of the public narrative. Though Modi appears to be taking a hard stance on China now, the damage has already been done.

Expectedly, Modi’s excessive preoccupation with protecting his image first and the party’s image second has only decreased India’s standing in the world. As India silences criticism and dissent, with an ever-tightening iron fist, and turns a blind eye to tragedy amidst a “once in a century crisis”, the international and domestic community has now begun to doubt India’s long-standing credentials as a liberal democracy. Modi needs to stop worrying about his image and start working on reality. The BJP is agitated, and perhaps understandably so. However, to save face by sticking its head in the ground is only going to exacerbate the situation.

Author Bio

Manjeeth S P is a Masters student in Political Science and International Relations at Indira Gandhi National Open University in India. His areas of interest are Indian foreign policy, political philosophy, political economies of marginalised communities, climate policy and education. He is currently preparing for the Civil Services Examination in India.

Mouzayian Khalil

Mouzayian Khalil

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…