All 4 entries tagged Gaming Pieces

No other Warwick Blogs use the tag Gaming Pieces on entries | View entries tagged Gaming Pieces at Technorati | There are no images tagged Gaming Pieces on this blog

March 01, 2019

MORA! A Roman token showing a game

Bronze token from the Julio-Claudian period. On one side two boys are shown seated facing each other, a tablet on their knees, playing a game. The boy on the right has a raised right hand. At the left is a cupboard or doorway (?); MORA above. On the other side is the legend AVG within a wreath. (From Inasta Auction 34, 24 April 2010, lot 381, Cohen VIII p. 266 no. 6, variant).

This token is part of a larger series of monetiform objects which are characterised by Latin numbers on the reverse. Some examples, like that shown here, have the legend AVG (referring to the emperor, Augustus) instead of a number. This same imagery, of two boys playing a game, is also found on a token with the number 6 (VI) on the other side; another example has the number 13 (XIII) on the reverse (Paris, Bibliothèque national no. 17088). This token series carry portraits of Julio-Claudian emperors or deities, or playful scenes, including imagery of different sexual positions (a sub category of tokens called ‘spintriae’ today).

|

|

We know this token is connected to the broader series from the Julio-Claudian period because of another specimen, now in the Ashmolean museum (Ashmolean Museum, Heberden Coin Room, photo no. 10544; shown left). This token carries the same design (AVG within a wreath) as the token above, and in fact the same die was used for both tokens (called a die link).

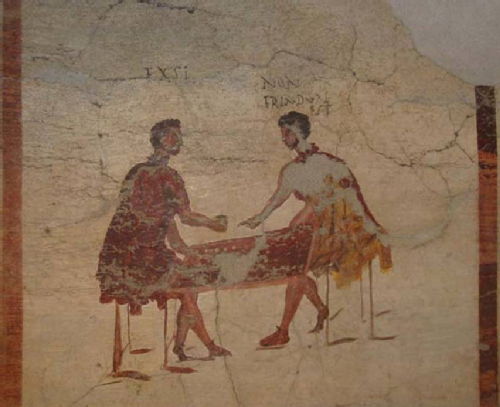

But what of the scene on the other side? Two men or youths sit opposite each other with a gaming board between them; the figure on the right raises his hand and there is a doorway behind the figure on the left. The word MORA sits above the scene: in Latin mora meant a pause or delay; it might also be used in a more imperative sense: wait! The word moraris is found on rectangular bone pieces whose function is also unknown but are thought to be gaming pieces (tesserae lusoriae). We thus have a scene of game play involving two individuals at a moment in time when one player is being asked to pause.

The scene is reminiscent of a painting from the bar of Salvius in Pompeii in which two men are depicted playing dice with their speech written above them - one declares 'I won' (exsi), while the other protests 'It's not three; it's two' (non tria duas est). Other paintings show the quarrel escalating, with the landlord eventually throwing the two individuals out of the bar.

|

The gaming scene on this token, as well as the numbers present on most of the tokens of this broader series, has led to the suggestion that these pieces functioned as gaming counters. However, unlike the bone gaming counters that carry numbers, these pieces have never been found together as a ‘set’, and don’t carry scratches that suggest they might have been used on a board (though this does not exclude their use in lotteries or similar). Instead it is possible that the scene was chosen because it communicates a feeling of fun. Lead tokens also carry numbers and similar scenes (including a scene of game play on a lead token said to be found in Ostia); these objects may have been used in festivals or other contexts associated with game play.

This blog entry was written by Clare Rowan as part of the Token Communities in the Ancient Mediterranean Project. It is based on a catalogue entry for a token that will feature in a forthcoming exhibition on ancient games and gaming in Lyon in June 2019, which is part of the Locus Ludi project.

Related Bibliography

Mowat, R. (1913). Inscriptions exclamatives sur les tessères et monnaies romaine. Revue Numismatique 67: 46-60.

Rodríguez Martín, F. G. (2016). Tesserae Lusoriae en Hispania. Zephryus 77: 207-20.

Rostovtsew, M. (1905). Interprétation des tessères en os avec figures, chiffres et légendes. Revue Archéologique 5: 110-24.

November 01, 2018

Fantasy Coins

This coin looks like a Roman coin. It is circular, it bears the head of the emperor, in this case Nero, and the legend (the writing on the coin) appears around the head. It is made of copper rather than the mixed-alloy bronze that was common in the Roman imperial period. However, the intent of the maker is to make a low value denomination. The lettering S C on the reverse (tails side) is a common feature for Roman issues in bronze, and the appearance of monuments, like the Ara Pacis in this case, is well attested. However, this is not a Roman coin, nor is it a modern imitation. This is a Fantasy coin; a coin reflecting the currency of a fantasy or an alternative history world.

Fantasy coins are produced by a number of different modern companies in response to the explosion of interest in fantasy games, such as Dungeon and Dragons. The coins can reflect specific worlds, such as Westoros (the world of Games of Thrones) or ancient Rome. Other ranges relate to generic fantasy worlds, particularly a specific racial or cultural group in that world. Elvish, dwarvern, barbarian, dragon and orcish communities are among the many catered for. Futuristic coins, representing the coins of imagined galactic empires, are also produced. In order to relate the coin to the subject matter, the images on the coin and more occasionally its shape are utilised. Such images are based on popular tropes related to the fantasy race. Dwarvern coinage for instance tend to show anvils, hammers and bear Nordic runes, ultimately derived from a Norse description of dwarfish smiths in the Prose Edda, a medieval text detailing Scandinavian myths. Orc coins often bear weapons or warriors, reflecting the original inspiration of orcs from Tolkien as creatures obsessed with war.

In many cases, a specific range of Fantasy coins is not tied to a particular game. The generic imagery is used so that the pieces can be accommodated in a number of different settings, allowing for a wider array of customers. The general audience of these coins are gamers and curiosity collectors, though these are often not separate groups. Players of “roleplaying” games, in which the players control characters in an imagined setting, with one player known by various names (Game Master, Dungeon Master or Keeper among many others) guiding the story. In these contexts, props are often utilised. These primarily consist of miniature figures representing the characters and their opponents, but increasingly other props are utilised to increase the immersion in the game. This is particularly evident in the real-world equivalent of role-playing, larping (otherwise known as live-action roleplaying) in which the participants physically portray their characters through costume and acting. Props are particularly valued in such settings, and the organisers of these events often produce their own coins. There are even events where complex denomination systems accompany the coins. For these groups, the coins are often bought in bulk. However, individual coins are also available for purchase. These would not be suited to games that require many coins, so these coins have a premium on their artistic value. As a result, Fantasy coins tend to be larger than most modern coins, and they often bear high quality designs. The Ancient Greeks also produced large coins with high quality images, so the use of coins as aesthetic pieces marks a continuation of an ancient tradition.

One would think that the coins would be highly unusual, as they are products of imagination. However, most fantasy coins are almost identical to the coins produced in the ancient period. The majority of fantasy coins are depicted as round objects, with an image on each side. Most ranges of fantasy coins have three separate denominations, with a gold, silver and copper issue. The only differences are the subject matter of images upon the coins and that they are not usually made of precious metal (like gold or silver), unlike the ancient coins which were intrinsically valuable in their own right. Since coinage began in 7th century BC Turkey, coins in the western world have retained the same features. Even Bitcoin is represented as a circular object, despite its digital form itself having no physical shape. Fantasy coins, for all the imagination behind them, are slaves to the trope. There are a few attempts to get away from round coinage for particularly exotic cultures, with some coins represented as moons, axe heads or as hexagons. In most cases, however, the producers of these coins are bound to their customers’ understanding of what a coin should look like.

Returning to our Fantasy Coin example, the coin copies a Roman issue in terms of its iconography (e,g, RIC 1 527). It is not, however, an imitation. The size of the original Roman denomination, an as, is not copied. As with other fantasy coins, the Nero coin is part of a series of gold, silver and copper coins, classed under the title “Roman”. As the smallest denomination, the coin is the smallest size in the series, whereas the gold coin is the largest coin of the set. In the ancient world, the size difference in coins was usually unnecessary; gold coins were intrinsically more valuable due to their metal content, so even the smallest gold coin was more valuable than the largest bronze coin and bronze coins were generally larger in antiquity. However, for modern Fantasy coins it would seem that bigger is better, so the highest denomination is afforded the largest size, and thus the greatest prestige. Within the series is a silver coin depicting a Constantine issue, and a gold coin bearing the Republican head of Roma, the titular goddess of Rome, with Jupiter riding a chariot alongside Victory on the reverse. The latter image was prominently featured on silver coins struck during the Roman Republic; the placement of the image on a gold coin here indicates that the modern manufacturer saw this image as worthy of a higher value.

|

|

|

Historical accuracy is not the intention behind these coins. What matters is the modern audience’s perception of what a coin is and what Roman culture was. Hence the more valuable coins are larger and the images chosen are ones that reflect “Roman-ness”. Hence emperors, monuments and famous gods are preferred over other images, like the many personifications of lesser deities that decorate the majority of ancient Roman coins. However, the manufacturers have chosen to imitate Roman coins rather than create their own images, so there is a modern desire for “authenticity” in some sense that the producers of these pieces are accommodating. This is not always the case; Fantasy Spartan coins exist, yet in reality the Spartans had no coins. As a result, standard pieces of Greek military equipment, like the Corinthian style helmet, are utilised for the iconography of these pieces.

The expansion in the Fantasy coin trade represents a continuation of coins as an art form. From their beginnings, coins in Europe bore high quality designs. The Rennes Patera show that certain individuals collected coins and valued them for the iconography upon them. There is little difference here.

Fantasy coins have yet to receive any major academic study. Yet studying these coins in an academic fashion is of great use in understanding modern conceptions. This is particularly true of the “historical” ranges of Greek and Roman coins. As a form of reception studies, one can see what particular images a modern audience considers as being “most Roman” or “most Greek”. The more fantastical ranges are also of interest, as it would be curious what real-world influences are attributed to these fictional races. Overall, the production of Fantasy coins shows that in the modern world where most transactions are carried out online or through credit, coins continue to attract interest.

|

This month's coin was written by David Swan. David is a postgraduate researcher at the University of Warwick. His thesis examines coinage and hoarding patterns across the Channel in Iron Age Europe. He specialises in Iron Age (otherwise known as Celtic) coinage.

June 01, 2017

Let's play with the portrait of Augustus! "Tesserae" and Roman Games

|

|

Bone gaming piece showing and naming Augustus.

(From Rostovtzeff's 1904 publication of the find).

|

A variety of objects are given the Latin label “tesserae” by modern scholars: mosaic pieces, lead monetiform objects, spintriae, and small circular objects made out of bone or ivory, like the piece pictured above. On one side is a carved portrait of Augustus, while the other side gives his name in Greek (Σεβαστός) and the number one in both Latin and Greek numerals (I in Latin, A in Greek; the Greeks represented numerals through letters). Scholars originally thought that these bone objects, found all over the Roman world, served as tickets to the theatre, amphitheater or circus. But then this “tessera” and fourteen others were found in a child’s tomb in Kerch (Russia) in 1903, and our understanding of these objects changed completely.

Fifteen bone “tesserae” were found in the tomb placed in a wooden and bronze box, neatly stacked in twos. Each piece had an image engraved on one side and on the other a word accompanied by a number in both Latin and Greek. The numbers range from 1 to 15. The designs of the pieces are as follows, according to the publication of Rostovtzeff 1905 (the counters are now in the Hermitage):

- Head of Augustus / CΕΒΑCΤΟC (Augustus), I and A.

- Head of Zeus / ΖΕΥC (Zeus), II and B.

- An "athletic head" (probably Hermes) / [ΕΡΜ]ΗC (Hermes? The legend is partly obliterated), III and Γ.

- Entrance to an Egyptian building / ΕΛΕΥΣΕΙΝ(ΙΟΝ) (Eleuseinion), IIII and Δ

- Head of Herakles / ΗΡΑΚΛΗΣ (Herakles), V and E

- The word ΗΡΑΙ(Α) (Heraia) in a wreath / YII and the letter vau

- Bust of a praetextatus (a young man wearing a toga) / ΛΟΥΚΙΟΥ (a referenece to a Lucius), VII and Z.

- Head of Kronos / ΧΡΟΝΟC (Kronos), VIII and H.

- The Greek letter Θ / ΠΑΦΟΥ in a wreath (shown below).

- Young female head with a hairstyle of the Augustan age / ΑΦΡΟΔΙΤ(Η) (Aphrodite), Χ and I

- Head of Pollux wearing an athletic headband / ΔΙΟCΚΟΡΟC (Dioscurus), XI and IA.

- Head of Castor wearing an athletic band / ΚΑCΤΩΡ (Castor), XII and IB.

- Head of Aphrodite / ΑΦΡΟΔΙΤ(Η) (Aphrodite), XIII and ΙΓ.

- Bust of Isis / ΙCIC (Isis). The inscription is damaged, but III and ΙΔ are visible.

- Head of Hera / [ΗΡ]Α (Hera, although the inscription is damaged), [X]V and IE.

|

|

Gaming piece no. 9, reproduced from

Rostovtzeff 1905.

|

Numerous other pieces similar to this have been found throughout the Roman world (e.g. Pompeii, Asia Minor, Athens, Syria, Crete, Vindonissa north of the Alps), but a complete set like this is rare, if not unique. Comparison with other pieces reveal that the numbers do not correlate with any particular image; so while Zeus is paired with number two here, on another set he may be number ten or fifteen, for example. Other pieces have the portraits and names of other emperors and empresses, though none later than Nero; some specimens represent Julius Caesar and one piece carries a portrait of a Ptolemy. This, in addition to the find spots (particularly in Pompeii, and in the abovementioned tomb) suggests a production date ranging from the second half of the first century BC to first century AD, although they may, of course, have been used later than this.

|

|

"Token", Early 1st century, Ivory. 2.9 cm

(1 1/8 in.) Gift of Marshall and Ruth

Goldberg. J. Paul Getty Museum, CC-BY.

|

This complete set has led scholars to conclude that these are gaming pieces. Many of the surviving specimens carry Egyptian, or more specifically, Alexandrian designs. Our number four, for example, likely represents a sanctuary in Eleusis, which was a suburb in Alexandria. Other suburbs in the city, for example Nikopolis, are also shown and named. On the right is an image of one of these pieces: an obelisk stands next to an Egyptian-style building; the other side names Nikopolis and provides the Latin and Greek number four: IIII and Δ. Egyptian deities feature alongside the busts of gods, rulers and other well-known personalities (e.g. athletes, poets, philosophers, characters from comedies). The current theory, then, is that this was an Alexandrian game that then became popular across the Empire in the first century AD. We have no idea how the game was actually played, although it might have been a mixture of a local Egyptian game and the Greek game of petteia (πεττεία).

We might pause to think what it meant that one could play a game in Pompeii, for example, or in modern day Russia, that represented and played with the Alexandrian landscape, its suburbs, buildings and gods. Could the experience be similar to a modern monopoly board, where British streets and locations are experienced and named by people all over the world? I think we should also consider that people thus might also ‘play’ with the emperor’s portrait; how then did this affect people’s experience of the emperor and his family? But finally, since these bone and ivory objects are gaming counters, we should probably stop calling them “tesserae”!

This Coin of the Month entry was written by Clare Rowan as part of the Token Communities in the Ancient Mediterranean Project.

Bibliography:

Alföldi-Rosenbaum, E. (1976). Alexandriaca. Studies on Roman Game Counters III. Chiron 6: 205-239.

Alföldi-Rosenbaum, E. (1980). Ruler portraits on Roman game counters from Alexandria (Studies on Roman game counters III). Eikones. Studien zum griechischen und römischen Bildnis. ed. R. A. Stucky and I. Jucker. Bern, Francke Verlag Bern: 29-39.

Rostovtsew, M. (1905). Interprétation des tessères en os avec figures, chiffres et légendes. Revue Archéologique 5: 110-124.

June 01, 2016

"Coins against Humanity"?

|

'Spintria' found in the Thames in 2012. PAS LON-E98F21 |

An Ancient Roman may not have been able to bring “Cards Against Humanity” to a pub game night, but they were able to bring spintriae. This particular sexy spintria was made famous when it was discovered in the Thames in 2012. There are several theories about the function of spintriae. People have suggested that they could be brothel tokens. Maybe the original owner of this token picked it up at the games? Or is it, as the title suggests, a game piece? One thing is for sure, the obverse is something that the user would remember and maybe even laugh at.

Two out of three theories are wrong. Suetonius wrote that Tiberius outlawed the use of coins stamped with the imperial image in bordellos (Clarke 1998: 244-245). This has led scholars to believe that these were brothel tokens. The idea that brothel customers would use these to pay for the services they wanted has been quickly dismissed (to see a more detailed discussion of this see Clare Rowan’s blog on this spintria).

This leads to the second theory. These tokens would be given to the public at public games. The idea this comes from a passage in Martial: “Now come sportive tokens (lasciva nomismata) in sudden showers.” (Martial Epigrams 8.78) These “sportive tokens” may be spintriae. That may seem like an odd token to give to spectators at public games celebrating things like military triumphs, but when considering the tensions in a society that placed importance on the lusts of men and the chastity of married women then maybe men receiving tokens to spend at a brothel might not be so bad (Knapp 2013: 236). However, this is not the case. The tokens would then be redeemed for gifts, but not at the local brothel. They could also provide a bit of a tough spot for an emperor who did not have the best press coverage. For example, viewers could be reminded of Tiberius’ sexual acts with boys on Capri (Suetonius Life of Tiberius 43-44). It is unlikely that an emperor, would want his people to snigger behind his back for what he got up to in his private life; thus, this theory seem implausible.

This leaves us with the third theory: these are game pieces. Although we don’t know what game these pieces were used with, we can be pretty sure that it was plenty of inspiration for the scenes of the game makers. There are other spintriae that have numbers going from I to XVI (1-16), but the sex scenes are different. This has led some scholars to believe that there is a correlation between the numbered spintriae and the illustrations of the sex manuals (Clarke 1998: 244, Clarke 2007: 194-5). This is also similar to the Pompeiian wall paintings found in the Suburban Baths. These are believed to have been numbered in a way similar to the lockers in the men’s changing room. As an added memory device, a taboo sex scene was placed above the number. The person using that space may not be able to remember his number, but they would probably be able to remember that funny dirty picture above it! (Savenga 2009).

This humour and function as a mnemonic device carried over to the game containing the spintriae. This spintria is tame compared to some of the other spintriae, so it was probably not one that was laughed too much. The steamy scene between this man and woman would have made the game memorable and may have reminded the player of what he had seen, read, heard, or even done. The fact that spintriae have been found in a widespread area, indicates that it Ancient Romans tended to have similar humour, played similar games, or that people loved this game so much that they brought it with them when travelling. Unfortunately, it may have been a male-only game. There were complaints [in Ancient Rome] that naughty pictures were corrupting respectable girls (Langlands 2006: 53). So, while the same sense of humour as a game of “Cards Against Humanity”, it might not have been a game to bring along to a game night with mixed company. However, it is not unreasonable to think that some clever minxes did manage to play “Coins Against Humanity”.

This month's blog was written by Katrina Anderson. Katrina is a Master’s student at Warwick University, who has recently become interested in the role of sex and gender in Ancient Roman art.

Bibliography

Clarke, J. (2007) Looking At Laughter. (London: University of California Press).

Clarke, J. (1998) Looking At Lovemaking. (London: University of California Press).

C. Rowan, Coins at Warwick: Ain’t talkin’ ‘bout love. Roman “Spintriae” in context.(1 Aug 2015). Accessed 10th May 2016.

Knapp, R. (2011) Invisible Romans. (London: Profile Books).

Langlands, R. (2006) Sexual Morality in Ancient Rome. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Martial, Epigrams, trans. Shackleton Bailey, D.R. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press: 1993) 2 vols. from Loeb Classical Library.

Sayenga, K. Sex in the Ancient World: Prostitution in Pompeii, Documentary, directed by Kury Sayenga (2009; New York: History).

Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, trans. J.C. Rolfe (London: William Heinemann: 1913) 1 vol. from Loeb Classical Library.

Clare Rowan

Clare Rowan

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…