All 9 entries tagged Coin Of The Month

No other Warwick Blogs use the tag Coin Of The Month on entries | View entries tagged Coin Of The Month at Technorati | There are no images tagged Coin Of The Month on this blog

December 01, 2013

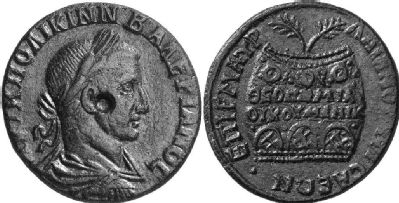

A coin of Nysa celebrating the 'Theogamia' or sacred marriage

|

| Coin of Nysa celebrating the sacred marriage |

My coin of the month comes from Nysa, a city in the Maeander valley in Asia Minor. Minted in the mid-third century AD, it shows the emperor Valerian I on the obverse while the reverse celebrates a festival held in the city, the ‘Theogamia,’ in honour of the ‘Sacred Marriage’ between Pluto and Persephone. The name of the festival is written in Greek letters inside a large prize crown: ΘEOΓAMIA OIKOY MENIK (Theogamia Oikoumenika). Two palms, the symbol of victory, emerge from the top. The epithet Oikoumenika indicates that the festival had been awarded international status, a mark of prestige in the bustling festival culture of the second and third centuries AD, when cities competed to attract performers to their games. Earlier coins do not include this title, and so this new type may have been minted specially to celebrate the new honour, which had to be awarded by the emperor.

The festival celebrates the sacred marriage between Persephone (daughter of the goddess Demeter) and the god of the Underworld, Pluto. Nysa proudly boasted a sanctuary of Pluto and Core (Persephone), as well as a cave thought to provide an entrance directly into the Underworld (Strabo 14.1.44-45). The Rape of Persephone, in which the maiden daughter of the goddess Demeter was seized by the god of the Underworld while she was out picking flowers, was a familiar myth in the ancient world, often used in funerary art as a visual metaphor for untimely death.

|

| Relief from the theatre at Nysa, showing Pluto’s pursuit of Persephone. |

The people of Nysa, however, put a more positive spin on the myth, and its associations with their territory, featuring it on the reliefs of their theatre as well as on coinage. According to the Homeric Hymn to Demeter (l.17) the abduction took place on the plain of Nysa, allowing the city to lay a strong individual claim to this well-known myth. Rather than stressing the destructive aspects of the myth, however, they asserted instead the importance of the union between Persephone and Pluto, as can be seen in the theatre reliefs, where Pluto is shown pursuing a hesitant Persephone, rather than dragging an unwilling bride into his chariot. Through this public festival they tied a universally-known myth to their particular local territory, asserting both their unique religious identity, and their place in a wider Greek world.

This coin shows the importance cities of the Greek world placed on their festival culture in the high Roman empire: both as a means to assert their local importance (often in rivalry with neighbouring cities), and to show their membership of the broader Hellenic religious community.

Dr Zahra Newby is Reader in Classics and Ancient History. Her research focusses on Roman art in its social context, in particular on Greek festival culture, ancient athletics, and the representation of myth in the Roman empire.

Further reading:

S. Mitchell, ‘Festivals, Games and Civic Life in Roman Asia Minor’ JRS 80 (1990) 183-193

Z. Newby, ‘Art and Identity in Asia Minor’, in S. Scott and J. Webster, (eds.) Roman imperialism and provincial art. (Cambridge, 2003).

S. Price, ‘Festivals and games in the cities of the east during the Roman Empire’, in C. Howgego, V. Heuchert, and A. Burnett eds., Coinage and Identity in the Roman Provinces (Oxford, 2005).

Coin image reproduced from Hack & Aufhauser, Auction 20, lot 490. Photo of theatre relief by Newby.

November 01, 2013

The YHD Coins of Judah

|

| Athenian Tetradrachm, 400-353 BC |

During the latter half of the fifth century BC, proud Athenians might have professed their coinage to be the world’s reserve currency; the ubiquitous ‘owls’ were recognised even in Persian-held territories. In the dying days of the Peloponnesian War, however, Athens found herself in both military and financial straits: to meet the costs of warfare, the citizens were reduced to plundering gold plate from the statues of Nike on the Acropolis, and the volume of newly-minted ‘owls’ entering circulation was drastically reduced. For undocumented reasons, a short time after, private and public individuals in the Persian satrapy of Judah began producing imitation coinage, featuring Athenian iconography.

Spot the Difference

Our two coins were both minted in the fourth century bc. The silver Athenian tetradrachm is an easily identifiable type: the well-defined helmeted head of Athena on the obverse; the owl, olive spray and the lettering ΑΘΕ [ΝAION] “of the Athenians” on the reverse. At first glance, the design on its counterpart, a Jewish obol, looks like a poor man’s copy. Athena’s features are somewhat oriental, and the owl has lost some fine detail. Perhaps Near Eastern die-engravers were unable to reproduce the Athenian images, or maybe, more likely, the need for a pixel-perfect replica simply didn’t exist. If official ‘owls’ were only required in the Near East and Transjordan for long-distance trading, any political significance of the images would have been lost – it was the worth of the metal that mattered.

|

| Persian YHD coin of Judah, 375-332 BC |

The clearest difference between the two coins is the reverse legend, which on the Jewish coin, is written in paleo-Hebrew and reads YHD (sometimes YHWD). This name is used in the Bible when referring to the satrapy of Judah during the Persian period; also, it is found impressed upon the handles of contemporary jars excavated in Jerusalem. Hence, the legend is openly advertising the provenance of the coin: no one is trying to ‘pass off’ this owl as an Athenian original. Similarly, the replacement of the olive spray with a lily on the reverse signifies its foreign mint: the biblical temple built by King Solomon had pillars decorated with ‘lily-work’, the lily being a traditional symbol of Jerusalem.

Small Change

Over time, especially after the conquests of Alexander the Great, the yhd coin types altered. Without apparent repercussions, the Athenian owl was replaced by a falcon; the profile of Athena by a male head. Yhd coins were never, it seems, consistent with Athenian weight standards and denominations. So we are left with the question: when they began minting, why did the Persian satraps in Judah borrow from the Athenians at all?

The answer is probably to be found in the persistent conservative trend which pervades numismatic history: in order for people to accept that something IS money, it has to LOOK like money. Athenian owls were so widespread during the latter half of the fifth century that local changes to coinage design were necessarily small, in order to preserve wider confidence in the metal’s worth. We might update the idea by imagining the suspicious glance which greets a Scottish five-pound note in Cornwall today: perhaps it is akin to the reception of a newly-minted silver coin in Jerusalem 2400 years ago, although in the ancient case, a lily rather than a thistle gives the game away.

This month's coin was chosen by Joe Grimwade, a second year undergraduate at the University of Warwick. He chose his 'Coin of the Month' after attending the British Museum's Numismatics Summer School, and is about to begin working with Warwickshire's Museum Service on their Roman coinage.

This month's coin was chosen by Joe Grimwade, a second year undergraduate at the University of Warwick. He chose his 'Coin of the Month' after attending the British Museum's Numismatics Summer School, and is about to begin working with Warwickshire's Museum Service on their Roman coinage.

Images above reproduced courtesy of Classical Numismatic Group Inc., (Electronic Auction 294, lot 306 and Electronic Auction 220, lot 194) (www.cngcoins.com)

October 01, 2013

Caracalla's "Profectio" Coin

|

| Profectio coin of Caracalla |

In AD 214, the emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninius Pius, nicknamed Caracalla after the Gallic tunic he allegedly wore, left Rome on a journey throughout the eastern provinces. The word PROFECTIO is used in Latin epigraphy to identify when an emperor sets out from Rome on a military expedition, and this word is seen on the legend on the reverse of this denarius. Minted in AD 213, this coin represents the sense of anticipation faced by Romans before the launching of such a force. Coins minted in the same year depict similar types as the coin we see here, as well as other military images such as the war god Mars. Whoever designed this coin, whether it be Caracalla himself or an imperial mint worker, clearly wanted to expose citizens to this upcoming event months in advance. Thus the coin acts as propaganda, advertising the emperor’s militaristic and proactive qualities.

The “Profectio” concept also gives the sense of beginnings being important in Roman life. The fact that the actual beginning of the expedition, rather than the expedition itself, is commemorated on this coin indicates the Romans considered the start of something to be just as worthy as the event itself. This suggests a sense of supreme confidence, as even before it has set off, the Romans believe this journey to be worthy of monumentalising through the medium of coinage, implying Romans were very optimistic about the success of their emperor and army.

The coin also reinforces the emperor’s own desire to be depicted in a military way. The type on the reverse of the coin displays Caracalla himself in military armour, carrying a spear, and it gives the impression of him personally leading the legions, represented by the standards behind him. This portrayal of himself as a great military leader is reinforced by the appearance of BRIT in the legend on the obverse of the coin, which represents “Britannicus”, or “Conqueror of the Britons”. While this title has been passed down from his father Severus (often done by Roman emperors), Caracalla himself can say he played a part in it, as he joined his father on his conquests. Accounts of the time indicate Caracalla actually played no significant role in his father’s Britannia campaign, but it is something an ordinary Roman would be unaware of. Thus even before his Profectio, Caracalla could identify himself as an experienced conqueror. Such a portrayal was probably designed to inspire support from the army, presenting the emperor as someone worth following, and whose rule they should support. However, this did not help him maintain his rule: whilst returning from his beloved Profectio, having dismounted to empty his bowels, he was murdered by a member of his Praetorian bodyguards close to the city of Edessa in Syria.

This month’s coin was chosen by David Swan, a second year Ancient History and Classical Archaeology undergraduate. David’s research interests involve Celtic, Roman and Dark Age Britain.

(Coin image above reproduced courtesy of Pecunem.com and Gitbud & Naumann)

September 01, 2013

A hoard of 201 antoniniani found in Eretria (Greece)

|

| View of modern Eretria and its ancient acropolis |

In 2011, a hoard of 201 antoniniani minted between AD 219 and 254 was found in Eretria on the island of Euboea during the excavations of the Swiss School of Archaeology in Greece (ESAG). So far, this is one of the biggest hoards of this time found in Greece, which makes it all the more interesting.

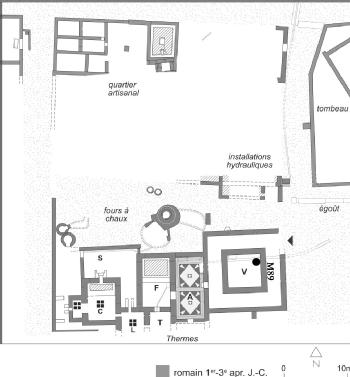

The hoard was found in the Roman bath building, buried next to a wall forming the impluvium in a peristyle courtyard giving access to the proper bath rooms.

Most of the coins belong to issues of the reign of Gordian III (238-244: 80 coins), Philip I (244-249: 86 coins) and Trajan Decius (249-251: 30 coins), with only a few minted under Elagabalus (218-222: 2 coins), Trebonianus Gallus (215-253: 2 coins) and Gallienus (253-268: 1 coin).

This kind of coin distribution appears to be characteristic of a number of hoards from Greece, Turkey or the Balkans ending under the joint reign of Valerian and Gallienus (253-260): Greece 1980 (254), Caesarea (255-256), Iasos (257-258) and Pergamum (258-259). Some hoards of this period like Göktepe (253) or Singidunum (254) still contain denarii, but none was recorded in the Eretria hoard, which explains why the proportion of coins minted before 238 remains insignificant.

|

|

Plan of the Roman bath of Eretria. The hoard was found against wall M 89 (© ESAG) |

While there are fewer coins of Trajan Decius (249-251) than his predecessors in quite a few of the hoards mentioned here, including the one from Eretria, it is possible to show that this is due to the shortness of his reign rather than to a reduction in the rate of hoarding. However, the rate of hoarding definitely slows down under Trebonianus Gallus (251-253) which seems surprising for hoards ending towards the end of Valerian and Gallienus' joint reign.

A study of the silver hoards buried in Greece during the 3rd century AD reveals that the coins in circulation in that region were replaced by new issues on a much faster basis than at the northwestern peripheries of the Empire (e.g. Britain).

The Eretria hoard appears to be typical of hoards ending between 251 and 264 that contain mainly issues minted between 238 and 251 (Mytilene, Cnossus, Greece 1980, Patras 1976, and Patras 1982). However, these issues seem to have almost completely disappeared from hoards buried after 265, towards the end of Gallienus' sole reign, when the antoniniani started to become heavily debased (Corinth 1930, Orchomenos, Chaeronea, Attica, Salamis, Athens 1955, Athens 1956, and Corinth 1936).

As most of the Greek hoards mentioned here are small in size (under 100 coins), they seem to reflect the daily coin circulation, which saw the disappearance of older, better coins from daily use.

So far, the Eretria hoard is the only one in Greece to show a small percentage of antoniniani minted in Antioch under Gordian III. As a general rule, the mint of Rome remains the only noteworthy supplier of coins in Greece up to Trebonianus Gallus. This changes under Valerian and Gallienus, when the coin supply from oriental mints increased suddenly to levels well above 50 %. The proportion of the Balkan mints however remained small at all times.

|

|

| Hoard in situ (© ESAG) | Hoard being removed during excavation (© ESAG) |

Dr Marguerite Spoerri Butcher is Associate Fellow of the University of Warwick and she works for the Swiss School of Archaeology in Greece.

Dr Marguerite Spoerri Butcher is Associate Fellow of the University of Warwick and she works for the Swiss School of Archaeology in Greece.

She has published, jointly with A. Casoli, a complete study of the Eretria hoard: «Un trésor d’antoniniens trouvé à Erétrie en 2011 questions de circulation monétaire en Grèce au milieu du IIIe siècle», Revue Suisse de Numismatique 91, 2012, p. 111-206, which can be downloaded here .

.

August 01, 2013

Severus Alexander and Amaseia

|

| Coin of Domitian showing the city of Amaseia |

Five hours east of Ankara by bus lies the modern provincial town of Amasya, perhaps better known today for the Ottoman houses that line its riverfront. In antiquity, as Amaseia, it owed its origins to the infighting that followed the division of Alexander’s empire and the power vacuums that sometimes developed. So for instance, on the death in 302 BC of Mithradates II of Cius, suspected of conspiring against Antigonus Monophthalmus, his son fled to Paphlagonia, occupied a stronghold at Cimiata and began the process of gaining control of the surrounding area, becoming in time Mithradates I Ctistes of Pontus. At some later stage the capital was moved to Amaseia itself, where the citadel formed an impregnable fortress from which to continue the expansion. By 250 BC it had acquired the coastal towns of Amastris, Amisus, and ultimately, in 183 under Pharnaces I, Sinope, which was to become the new capital of a kingdom now stretching from Amastris in the west to Trapezus in the east.

Nevertheless it is clear that in terms of royal associations, its strategic inland position, civic monuments and religion Amaseia continued to represent the true heart of Pontus, as its famous son, the geographer Strabo, makes clear (12, 3, 39):

My own city of Amaseia lies in a large and deep gorge through which flows the river Iris. As a result of both human ingenuity and nature it is wonderfully appointed, since at one and the same time it is able to serve as both city and fortress. For there is a high and precipitous rock which plunges down to the river, bounded on one side by the wall on the river’s edge, where the town is settled, and on the others by the walls that run up on either side to the peaks. There are two of these peaks which are connected to one another and rise up wonderfully to towering heights. Within this circuit of walls are the royal palace and the monumental tombs of the kings.

|

| Coin of Severus Alexander showing the city of Amaseia |

Even today the rock-cut tombs, the platform of the palace and the walls remain visible, and it is these that were to figure on more than one issue of its coins. While the numismatic origins of Pontus remain a matter of debate, by the reign of Pharnaces I (c. 185-156 BC) its coinage was well established, with the mint most probably located in Amisus, which was to remain the main producer. Under Mithradates VI (c. 120-63 BC), however, Pontus experienced a veritable explosion in production in order to finance the three wars that Mithradates waged against Rome. In terms of gold and silver, issues offer important clues as to production schedules, with coins bearing not only the year of production according to the Pontic calendar, but even the month of production. Base-metal coinage, in turn, issued in a variety of denominations, has its own remarkable feature, in that issues bear the name of their ostensible origin, a total of fourteen locations, including Amaseia.

|

| Rock cut tombs at Amaseia |

With the final collapse of the kingdom before the might of Rome there was an inevitable hiatus in the coin-record, with Amaseia ostensibly only re-emerging in the reign of Tiberius. Thereafter, however, production flourished as troops on the eastern frontier were periodically augmented and campaigns waged, and we find reverse motifs honouring at times not only the emperors of the day, but also gods such as Athena, Hades/Serapis, Apollo, Asclepius, Tyche and Ares with Aphrodite. Architecture too figures as a reverse motif in the form of a temple, perhaps that of Zeus-Stratios, a Hellenised version of the Persian Ahura-Mazda, which, with its associated fire-altar and adjacent tree, crowned the citadel. The altar and tree themselves form an important motif on several issues and mirrored, in fact, the sanctuary of the god which lay on a mountain peak to the east of the city and is associated with enormous sacrificial holocausts described by Appian (Mith. 66, 70) in the context of Mithradates VI’s defeat of Murena in 82 BC and the invasion of Bythinia in 74. A further temple, that of the Great Mother, is referred to by Gregory of Nyssa (De S. Theodoro Mart., Patrologia Graeca 46, p.744a), “There was a temple to the fabled Mother of the Gods in the metropolis of Amaseia, which the pagans of that time in the conceit of their folly built beside the banks of the river.”

The first representation of the city as a whole on coinage comes in the reign of Domitian (AD 81-96), a schematic view of towers along the city walls, a temple in the foreground, evidently that of the Great Mother, and on the summit of the citadel another with, to its left, seemingly, a representation of the altar and tree associated with Zeus-Stratios. The larger module issue of Severus Alexander, in contrast, (dated AD 225-6 – ET CKH) brings much of this into greater relief: to left and right the circuit of walls with their impressive towers, still visible to some extent today, in the foreground-centre, on the banks of what would be the river Iris, is clearly the temple of the Great Mother referred to by Gregory; to its left a rock-cut tomb, while above the cliff-face rises to the summit bearing more clearly this time the temple of Zeus Stratios, with a fire-altar to its right. Of this last edifice nothing remains today, replaced by the remains of Byzantine and later fortifications, hence the significance of the coin as an architectural point of reference.

The coin as selected by Stanley Ireland, Emeritus Reader in the department, is one of over 4,500 coins he catalogued in the museum at Amasya/Amaseia.

July 02, 2013

A provincial coin of Ephesus showing Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus flanking the cult statue

The relationship between Rome and Greece was complex, as Rome admired Greece for its higher culture, but was afraid of how it could influence changes in the political and social structures of the empire. Eventually the two cultures mixed during the Roman conquest and we can see that a balance was struck between the reverence shown to the Roman Emperors and provincial imagery. This balance can be seen particularly in the coinage of Ephesus where the majority of coins show the Roman Emperor on the obverse, and local images emphasised civic pride on the reverse.

as Rome admired Greece for its higher culture, but was afraid of how it could influence changes in the political and social structures of the empire. Eventually the two cultures mixed during the Roman conquest and we can see that a balance was struck between the reverence shown to the Roman Emperors and provincial imagery. This balance can be seen particularly in the coinage of Ephesus where the majority of coins show the Roman Emperor on the obverse, and local images emphasised civic pride on the reverse.

As in the case of this bronze coin from the rule of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, there was a substantial amount of coinage from this province depicting the cult statue of the Ephesian Artemis. The Ephesians, going against traditional Greek conviction, believed that the divine twins Artemis and Apollo were actually born in their city. The Ephesians mainly worshipped Artemis as a fertility goddess, which resulted in their cult statue differing enormously from traditional depictions of her in mainland Greece, where an emphasis was traditionally put on Artemis’ role as a huntress. The inclusion of the Ephesian Artemis on such coins demonstrates the pride that the Ephesians took in their local political and cultural traditions. The inclusion of the cult statue also gives us an idea of the way the Ephesians viewed the Roman conquest. While Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus are shown on the reverse as well, the fact that the statue takes the central focus shows that the traditional gods of the Ephesians were more important to them than other gods brought to them through the conquest.

While the image of Marcus Aurelius on the obverse serves to show the relationship between Ephesus and Rome, and in many ways the dominance of Rome over this particular province, the inclusion of the Ephesian Artemis shows that the Ephesians also felt that the need to demonstrate their own power. The inscription ΝЄΟΚ on the reverse also serves to show the power and rank of Ephesus at the time. Neokoros is a title that appears a lot on ancient coinage, originally given to officials who were in charge of the upkeep of sacred buildings and their artefacts. By the time of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus it referred to cities that had local temples to the imperial cult. It seems as if rivalries between cities often motivated them to strive for this recognition, and the inscription on this coin is evidence for the civic pride gained by winning the title.

This month's coin was chosen by Emily Morgan, a final year undergraduate. While her dissertation focused on the attitudes towards death in Greek literature, she is an avid coin collector and is passionate about expanding her knowledge of classical numismatics.

This month's coin was chosen by Emily Morgan, a final year undergraduate. While her dissertation focused on the attitudes towards death in Greek literature, she is an avid coin collector and is passionate about expanding her knowledge of classical numismatics.

(Image above reproduced courtesy of Classical Numismatic Group Inc., (www.cngcoins.com))

June 02, 2013

A medallion showing the arrival of Asclepius in Rome

Writing about web page http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/classics/research/coinage

As often in ancient history,  the decision to bring Asclepius, the god of Medicine, to Rome was made in order to avert a pestilence against which remedies of the time were powerless. In 293 BC, following an oracle from Delphi, the Roman senate decided to bring the cult of Asclepius to the Urbs. For this purpose, they sent delegates to Epidaurus, the most famous Asclepius shrine of the time, in order to fetch one of the sacred snakes of Asclepius and carry it back to Rome on a ship. Similar epidemic outbreaks, combined with human helplessness in the face of disease explain the spread of the cult of Asclepius from the 5th c. BC onwards.

the decision to bring Asclepius, the god of Medicine, to Rome was made in order to avert a pestilence against which remedies of the time were powerless. In 293 BC, following an oracle from Delphi, the Roman senate decided to bring the cult of Asclepius to the Urbs. For this purpose, they sent delegates to Epidaurus, the most famous Asclepius shrine of the time, in order to fetch one of the sacred snakes of Asclepius and carry it back to Rome on a ship. Similar epidemic outbreaks, combined with human helplessness in the face of disease explain the spread of the cult of Asclepius from the 5th c. BC onwards.

Upon arrival to Rome, it is said the sacred snake jumped out of the boat into the Tiber, and landed on the island (today Isola Tiberina). The temple of Asclepius was built on this very site, for, it was thought, the god himself had chosen the location of his future home! The ‘medical’ function of the island has survived to our day: where the temple of Asclepius stood now lies a hospital.

|

|

This fine bronze medallion illustrates that famous episode of Roman history. A rare, precious piece in itself, this medallion dating from Antoninus Pius’ reign (138-161 AD) can in fact be connected with a wide range of visual representations of the Asclepian cult and of Roman legendary history. Like other medallions of Antoninus Pius, it refers to famous Roman events in an attempt to connect the present with the distant, heroic past. Not all details are perfectly visible here, but the image has several striking features, such as the archs of a bridge over the Tiber, the Tiber itself in the shape of a bearded river-god, and several buildings which may or may not have stood on the island – the snake seems to gaze at them, which could indicate that they were placed on the Isola Tiberina. At the centre of the medallion, the artist has captured the very moment when the snake, ‘standing’ at the prow of the galley bringing him to Rome, is about to jump into the Tiber and swim across to the shore of the island where the temple is to be built. Other representations of the same event exist in a variety of formats (notably a famous relief on the island itself, shown below right), and they reflect a more general pictorial theme of the gods’ arrival in a given place. Above left is a famous 2nd c. AD mosaic in Cos that shows Asclepius setting foot on the shore of the island, with Hippocrates sitting there, to welcome him.

This month's coin is chosen by Dr. Caroline Petit, a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow in Classics at Warwick who works on ancient medicine.

This month's coin is chosen by Dr. Caroline Petit, a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow in Classics at Warwick who works on ancient medicine.

(Coin image above reproduced courtesy of Baldwin's Auctions Ltd, New York Sale XXV, lot 185)

May 02, 2013

A PROVINCIA DACIA sestertius from the third century AD

Writing about web page http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/classics/research/coinage

This month’s coin is a sestertius  of the PROVINCIA DACIA coin series. PROVINCIA DACIA was a local coinage in the middle and lower Danube area during the 3rd century AD. It mainly circulated in the provinces of Dacia and Pannonia, as suggested by site finds. A close analogy can be established with another roughly contemporary bronze coinage P M S COL VIM (Provinciae Moesiae Superioris Colonia Viminiacum), which was issued at Viminacium in Moesia Superior between AD 239 and 257. The research of C. Gãzdac suggests that the main role of these coins was to supply the army. The PROVINCIA DACIA coin series can therefore be closely linked with the military and their need for bronze coinage in Dacia. This hypothesis is supported by site finds from the territory of this province. For example, at the militarised site of Porolissum, 64% of the PROVINCIA DACIA coins minted during the reign of Philip I were retrieved from the territory of the fort (Á. Alföldy-Gãzdac, C. Gãzdac, The coinage ‘PROVINCIA DACIA’ – a coinage for one province only? (AD 246-257), in Acta Musei Napocensis, 39-40/I, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2002-2003 (2004), p. 247-258).

of the PROVINCIA DACIA coin series. PROVINCIA DACIA was a local coinage in the middle and lower Danube area during the 3rd century AD. It mainly circulated in the provinces of Dacia and Pannonia, as suggested by site finds. A close analogy can be established with another roughly contemporary bronze coinage P M S COL VIM (Provinciae Moesiae Superioris Colonia Viminiacum), which was issued at Viminacium in Moesia Superior between AD 239 and 257. The research of C. Gãzdac suggests that the main role of these coins was to supply the army. The PROVINCIA DACIA coin series can therefore be closely linked with the military and their need for bronze coinage in Dacia. This hypothesis is supported by site finds from the territory of this province. For example, at the militarised site of Porolissum, 64% of the PROVINCIA DACIA coins minted during the reign of Philip I were retrieved from the territory of the fort (Á. Alföldy-Gãzdac, C. Gãzdac, The coinage ‘PROVINCIA DACIA’ – a coinage for one province only? (AD 246-257), in Acta Musei Napocensis, 39-40/I, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2002-2003 (2004), p. 247-258).

This month’s coin was struck during the first year of the local era, i.e. AD 246. This can be seen on the reverse side, in the exergue, which contains the formula AN I (annus I, lat.). This year coincided with the imperial presence of Philip I in Dacia during the Carpic invasion. The obverse of this sestertius depicts the imperatorial bust of Philip I in military dress – he is wearing a cuirass, and his head (facing right) has a laureate crown.

The legend is inscribed with the emperor's name: IMP(erator) M(arcus) IVL(ius) PHILIPPVS AVG(ustus). The military theme of the reverse is in line with the intended audience for this coinage. It depicts the province of Dacia standing left, between an eagle and a lion. The eagle with a wreath in its beak and the lion are symbols of the legions permanently garrisoned in Dacia, the legio V Macedonica from Potaissa, and the legio XIII Gemina from Apulum. Moreover, the olive branch, the curved Dacian sword (falx), and the standard inscribed D(acia) F(elix) are also of a military character. Finally, the legend on the reverse is inscribed PROVINCIA DACIA.

The importance of this coin, struck in the first year of the local era, is suggested by the high volume of this coinage in Dacia during the reign of Philip I (estimated by C. Gãzdac at almost 40%), and by its intended audience. The mint where this specimen was struck remains debatable. However, recent scholars have provided convincing arguments for Apulum.

The importance of this coin, struck in the first year of the local era, is suggested by the high volume of this coinage in Dacia during the reign of Philip I (estimated by C. Gãzdac at almost 40%), and by its intended audience. The mint where this specimen was struck remains debatable. However, recent scholars have provided convincing arguments for Apulum.

This month's coin was chosen by Elena Marchis, an MPhil/PhD student in Numismatics at Warwick.

(Coin image above reproduced courtesy of Numismatik Lanz München)

April 08, 2013

April's Coin of the Month

Writing about web page http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/classics/research/coinage/

An intriguing Roman provincial coin depicting an Armenian tiara

This month’s coin  presents an intriguing type, the classification of which remains undetermined. The obverse depicts jugate busts facing right. The device on the reverse is unquestionably an Armenian tiara with its distinctive pointed spikes on top and neck and ear flaps hanging from the bottom. Parts of a circular legend are visible, but remain mostly illegible (published in RPC Supplement II, no. S2-I-5488, AE 8.76g). Thus far only two other issues are known depicting an Armenian tiara: the denarii of Mark Antony (Sydenham, The Coinage of Caesarea in Cappadocia, 1205) and Augustus (Roman Imperial Coinage, Vol. I, 516). The attribution of this unique coin remains uncertain. The portrait is unquestionably that of a Julio-Claudian, but it is difficult to identify the emperor with certainty without the aid of a legible legend. Despite this, a number of candidates may be proposed.

presents an intriguing type, the classification of which remains undetermined. The obverse depicts jugate busts facing right. The device on the reverse is unquestionably an Armenian tiara with its distinctive pointed spikes on top and neck and ear flaps hanging from the bottom. Parts of a circular legend are visible, but remain mostly illegible (published in RPC Supplement II, no. S2-I-5488, AE 8.76g). Thus far only two other issues are known depicting an Armenian tiara: the denarii of Mark Antony (Sydenham, The Coinage of Caesarea in Cappadocia, 1205) and Augustus (Roman Imperial Coinage, Vol. I, 516). The attribution of this unique coin remains uncertain. The portrait is unquestionably that of a Julio-Claudian, but it is difficult to identify the emperor with certainty without the aid of a legible legend. Despite this, a number of candidates may be proposed.

A likely candidate is Augustus, for it was during his reign that pro-Roman rulers were established on the Armenian throne on several occasions. In 5 BC Augustus dispatched Roman forces under the leadership of Tiberius, who appointed Artavasdes (a grandson of Tigranes the Great) to the throne. Upon the death of Artavasdes, his son Tigranes was successful in petitioning Augustus for the kingship and arrangements were made for him to receive the crown from Gaius Caesar in Syria. The following years saw a number of rulers appointed by Augustus, including members of the ruling dynasty of Media Atropatene and a scion of the house of Herod the Great. In consequence, this type may have been issued to commemorate any of the above events. During Tiberius’s reign, Rome once again was involved in Armenia’s political affairs, when in AD 18 the Emperor dispatched Germanicus to place Zeno, son of King Polemo of Pontus, on the Armenian throne to resolve a political vacuum. Drachms and didrachms were issued in Caesarea in Cappadocia to commemorate this event. It may be the case that these bronzes were issued for the same occasion, although not necessarily at the same time and place. Nero is also a likely candidate, for it is well recorded that in AD 66 Tiridates, the pro-Parthian king of Armenia, received his crown from the Roman emperor during a lavish ceremony in Rome; these coins may have been issued to celebrate this occasion.

As for the second portrait, it is highly unlikely that it is one of the above mentioned Armenian kings, since there is no precedent for the representation of a ‘client king’ jugate with a Roman emperor on the obverse. The second person is most probably a member of the imperial family, though difficult to identify without a legible legend.

This month’s coin was chosen by Jack Nurpetlian, who recently completed his PhD thesis on the Roman period coinages of the Orontes Valley in Syria. Jack’s research focuses on Roman provincial coins of the Syro-Phoenician territories, in addition to his personal interest in ancient Armenian coins.

(Coin image reproduced from The Roman Provincial Coinage Supplement II, www.uv.es/~ripolles/rpc_s2)

Clare Rowan

Clare Rowan

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…