All 29 entries tagged Coin Of The Month

No other Warwick Blogs use the tag Coin Of The Month on entries | View entries tagged Coin Of The Month at Technorati | There are no images tagged Coin Of The Month on this blog

August 01, 2015

Ain't talkin' 'bout love. Roman "Spintriae" in context.

|

| Roman token, found in the Thames, PAS LON-E98F21 |

In 2012 this token was found in the Thames in London, resulting in numerous news articles about this 'brothel token'. The obverse carries the Roman numeral XIIII (14), while the reverse carries a sex scene. The couple are laying on a decorated bed or a couch, the woman laying on her front while a male straddles her.

This token is part of a broader series that carry a Roman numeral between 1 and 16 on one side, and various sex acts on the other. Another series carry Roman numerals on one side and portraits of Augustus, Tiberius or Livia on the other (see below). Buttrey analysed the dies of both series and concluded they were connected; he suggested that these objects date to the Julio-Claudian period and were perhaps gaming tokens, envisaging a possible scenario where one side played 'the imperial portraits' and the other 'the sex scenes', making the game a form of salacious gossip on the sex lives of the Roman emperors.

|

| Roman token showing Tiberius and XII within wreath. |

In reality, we know very little about these objects; their sexual scenery has created numerous forgeries, and very few archaeological contexts are known. They are often called spintriae, a label created in the modern era from a reading of Suetonius' Life of Tiberius. As part of the portrayal of Tiberius' activities on Capri, Suetonius records the presence of numerous female and male prostitutes, called spintrias (Suet. Tib. XLIII, see also Tacitus, Ann. VI.1; sphinthria or spintria referred to a male prostitute in Latin, from the Greek σφιγκτήρ, and connected to the Latin/modern word sphincter). It is this tale that inspired early collectors and scholars to label these objects spintriae, and when a hoard of tokens was found on Capri it cemented the name, though they were not called this in antiquity.

Indeed, the known find contexts of these objects suggest they had little to do with sex. Although hundreds of these specimens exist (precise numbers are difficult given the quantity of fakes in existence), only a handful of closed archaeological contexts are known. We cannot know whether the Thames example was lost in antiquity, or more recently. But one example was recently found in a tomb in Mutina; associated ceramics and other coins dates the tomb to AD 22-57, suggesting Buttrey's dating of the Julio-Claudian period is correct. Another was found during an archaeological campaign on the island of Majsan; this was pierced, suggesting it had been transformed into a piece of jewellery. Scattered other examples are reported to have been found in Caesarea Maritima, in the Garigliano in Italy, on Skegness beach (likely a modern loss) and in Germany (Stockstadt am Main, Saalburg, Nendorp-Wischenborg; these are sporadic finds). Although the information on the find places of these objects leaves much to be desired, none of these find spots are brothels, and in each example there is only one 'spintria' found. What their purpose was remains a mystery. Like many Roman tokens, much more study is required before we can fully understand these objects.

This month's coin was chosen by Clare Rowan. Clare is a research fellow at Warwick, who has recently become interested in the role tokens had in Roman society.

Coin images above reproduced courtesy of the Portable Antiquities Scheme and © The Trustees of the British Museum

Select Bibliography:

Benassi, F., N. Giordani and C. Poggi (2003). Una tessera numerale con scena erotica da un contesto funerario di Mutina. Numismatica e Antichità classiche 32: 249-273.

Buttrey, T. (1973). The spintriae as a historical source. Numismatic Chronicle 13: 52-63.

Martini, R. (1997). Tessere numerali bronzee romane nelle civiche raccolte numismatiche del comune di Milano Parte I. Annotazione Numismatische Supplemento IX: 1-28.

Mirnik, I. (1985). Nalazi novca s Majsana. VAMZ 18: 87-96.

July 01, 2015

Augustus and the gods

RIC Augustus 367, BMC Augustus 98 = LACTOR, Age of Augustus L1. Silver Denarius, 16 BC

Obverse: Bust of Venus right. C ANTISTVS VETVS IIIVIR = ‘Gaius Antistius Vetus, tresvir (monetalis)’

Reverse: symbols of priestly offices – the ladle (simpulum) top left, augur’s wand (lituus) top right, tripod bottom left and sacrificial bowl (patera) bottom right. COS IMP CAESAR AVGV XI = ‘Imperator Caesar Augustus, consul for the 11th time’.

|

| Gemma Augustea |

Res Gestae divi Augusti 7.3 ‘I have been chief priest, augur, one of the Fifteen for conducting sacred rites, one of the Seven in charge of feasts, Arval brother, member of the fraternity of Titus, and fetial priest.’ Many passages of the Res Gestae find echoes in contemporary coinage. For Augustus, this list of his priesthoods was just as important as the magistracies which he had listed in the previous sentence. It was a common sentiment in Roman texts that the Romans’ divisive civil wars was a consequence of their neglect of the gods, who in turn then punished the Romans by provoking them to fight each other rather than the barbarian enemy who ought in the normal course of events to be the focus of any warfare. So the solemn opening of one of Horace’s so-called ‘Roman Odes’, 3.6, states ‘Ancestral crimes, though innocent, you’ll pay the gods for, Roman, till you restore their temples, their crumbling shrines, and images with black smoke besmirched’ (LACTOR G28). It is a commonplace to point out that, for Romans, their magistrates were their priests, and that religion and politics were regarded as inseparable. A Roman would not have understood the modern criticism made by some in contemporary Britain whenever a bishop or archbishop takes a stand on a point of politics.

|

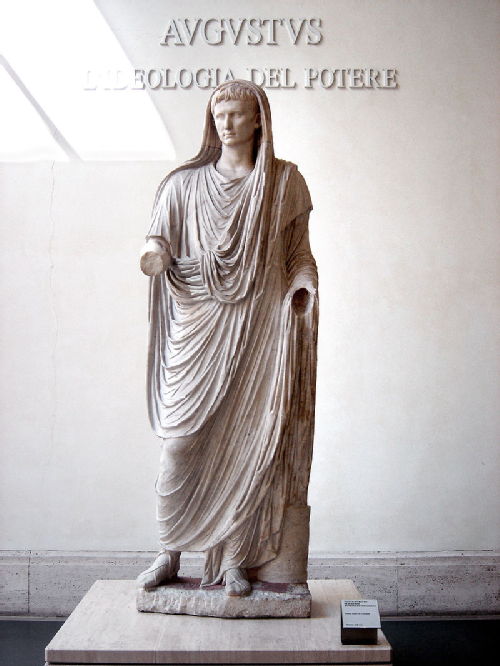

| via Labicana Augustus |

But in Augustus’ case, this coin is an excellent example of his typical blend of tradition and radical innovation. The presence of Venus on the obverse reminds us of the claims made by the Julian family to be descended from the goddess herself, via Aeneas, whilst the images on the reverse allude to the four major priesthoods in Rome. The ladle alludes to the pontifices, who had overall control of state cults; the lituus is both the wand used by the augurs in taking the auspices by observing the flight and song of birds and also a visual pun upon Augustus’ own name (compare too its appearance in Augustus’ hand on the gemma Augustea); the tripod alludes to the quindecimviri sacris faciundis, the college who were in charge of foreign cults in Rome, including consultation of the Sibylline oracle and the celebration of the Centennial Games; and finally, the patera recalls the college of the septemviri epulones in charge of sacred feasting at Rome. Traditionally, an individual held only one priesthood for life. Augustus had first been made a pontifex as early as 47 BC, in place of Domitius Ahenobarbus who had been killed at the battle of Pharsalos: he owed this promotion to the influence of his great-uncle Julius Caesar, who himself had exceptionally been a member of three priestly colleges. But it was Augustus who ended up as the first Roman ever to be a member of all four major colleges (and several minor ones too), accumulating them gradually over time, being elected augur in c.42 BC, quindecimvir in c.37 BC, and septemvir by 16 BC. One of the statues of Augustus most famous today – the via Labicana statue from Rome – depicts him in his role as priest, with veiled head. He makes the multi-titled Pooh-Bah of Gilbert and Sullivan’s Mikado – ‘First Lord of the Treasury, Lord Chief Justice, Commander-in-Chief, Lord High Admiral, Master of the Buckhounds, Groom of the Back Stairs, Archbishop of Titipu, and Lord Mayor, both acting and elect, all rolled into one’ – look almost unambitious! Both of these characters – though one fictional and the other real – may be compared for the way in which they both managed to bundle together the functions of the state into their own person. As Tacitus claimed, in the opening of the Annales, ‘he gradually increased his power, arrogating to himself the functions of the senate, the magistrates, and the law’.

By the end of Augustus’ lifetime, the link between Rome’s prosperity, the goodwill of the gods, and Augustus himself as the crucial intermediary with the gods in securing their support for Rome, was a message that was clear from a variety of visual and textual media.

This month's coin was chosen by Alison Cooley. Alison usually devotes her energies to Latin inscriptions, but is always delighted to have an excuse to look at coins too. Her commentary on the Res Gestae (CUP 2009) discusses other ways in which coins overlap with the messages promoted by that fascinating inscription. She is currently working on a project re-editing Latin inscriptions in the Ashmolean Museum: see our blog, Reading, Writing Romans.

Coin image © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Gemma Augustea CC-BY-SA 3.0 ("Gemma Augustea" by Dioscurides (?) - Self-photographed, October 2013 (James Steakley). Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons)

via Labicana Augustus from Wikimedia Commons. ("CaesarAugustusPontiusMaximus" by RyanFreisling at English Wikipedia - Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons)

June 01, 2015

Aes Grave

Compared with most of the Greek world Rome was a latecomer in its adoption of coinage; one might say indeed that it blundered its way onto the numismatic scene in a way that is really only understandable in the context of its geographical and cultural position within central Italy. The virtual absence of precious metals from the area, except what could be acquired through trade, tribute or war-booty, meant that the region’s medium of exchange had long been copper alloy. This had initially taken the form of rough pieces of metal (Aes Rude), which had to be weighed out to gauge their value. One stage on from this are cast ingots associated with Rome’s neighbours, often bearing dry-branch motifs (hence the description Ramo Secco) and usually found broken into smaller units. This idea the Romans adapted to produce their own ingots (Aes Signatum) bearing a variety of motifs (shields, sword & scabbard, cattle, elephant and pig, tripod and trident) – and of various weights: from c. 1000g. to 1850g.

|

|

Aes grave coin with the head of Janus on the obverse and a prow on the reverse.

Round coinage, such as we would recognise, in the context of Rome, though, is curiously not at first the product of Rome itself but of the Greek colony of Naples to the south: silver and copper issues bearing the name of Rome but with a man-headed bull motif that is clearly a reference to Naples. Probably produced in the last decades of the fourth century, their purpose remains obscure – perhaps to record some treaty between the two states. Certainly their rarity does not suggest a significant commercial purpose. In the early decades of the third century more silver issues more evidently Roman begin to appear, though whether actually produced in Rome is a moot point since their style is clearly still Greek. Internally, however, Rome itself was still wed to the idea of bronze and, more significantly, to the idea that weight of metal and value went hand-in-hand. Hence what appeared was the weighty Aes Grave coinage, based on the As unit of account, often weighing in the region of 320g., fractioned down to a twelfth, and in the case of the very first issue (the so-called Janus-Mercury issue because of the motifs on obverse and reverse) down to a twenty-fourth. For a period of some ninety years this currency formed the staple medium of exchange, the only variation being changes of motif (e.g. the Apollo-Apollo series, the Wheel series), and around the middle of the century a lightening of the As to 280g., perhaps in order to bring base metal and silver into some kind of relationship. Rome’s apparent fixation with weight and value, however, was not to last. Around 225 BC the last Aes Grave series was issued, the so-called Prow-series, bearing the two-faced image of Janus on the obverse of the As and the prow of a galley on the reverse, as in the illustration here. Again this basic unit was fractioned, with the head of Saturn on the half, Mars on the third, Hercules on the quarter, Mercury on the sixth, and Roma on the twelfth, and with the prow reverse common to all denominations. And, if such clumsy coinage were not enough, Rome also minted a now-unique monstrous 5-As piece, doubtless on the analogy of the three- and two-As pieces of the Wheel series.

The system, though, was to suffer serious disruption when in 218 BC Hannibal invaded Italy and severed Rome from its metal supplies. In short, Rome went bankrupt and for a time waged war on credit from its citizens. The effect must have been catastrophic: to conserve metal, over a period of six years the Aes Grave suffered a series of weight reductions till in 212 it was a mere sixth of what it had been; the silver coinage being issued underwent a drop in both weight and fineness of the metal –content until it was abandoned and replaced by a new silver coinage (the denarius), and gold as an emergency currency began to appear. It cannot be underestimated to what extent the losses in manpower and resources affected the city; yet within a decade of 212 Rome was to emerge victorious over Carthage, became the dominant power in the western Mediterranean, and had produced a new currency that was to remain essentially standardised for the next two hundred years.

This month's coin was written by Stanley Ireland, an emeritus reader in the department.

May 01, 2015

In the shadow of a dictator

|

|

Coin of Titus Carisius

Obverse: Victoria right, SC behind. Reverse: Victory driving a Quadriga, T.CARISI in exergue (Sydenham 985, Crawford 464/5)

If one were to poll 100 individuals about the name ‘Titus Carisius’, all 100 would be forgiven for having never heard of him. His appearance in the Roman Republican monetary record is simply overshadowed by the folklore popularity of contemporary figures such as Pompey the Great and Julius Caesar. Even Roman historians only briefly record the exploits of the gens Carisia, the lineage from which Titus descends. Cassius Dio refers to a ‘Titus Carisius’, presumably the same individual as our moneyer, defeating the native Astures in the province of Hispania and founding a colonia there (Dio LIII.25.8). However, the later historian Florus records the same feat of 25BC as the exploits of a legate with the praenomen ‘Publius’ not ‘Titus’ (Epitome II.33; Florus lived from c. 70 – 140 AD). It would appear from the subsequent coinage of the new colonia founded for the Legio V Alaudae and Legio X Gemina that Florus was correct in his documentation as coin legends clearly record P. CARISI as the legate and pro-praetor. Such confusion therefore compounds the disappearance of Titus Carisius from history. This article seeks to re-establish this forgotten triumvir monetalis of 46 BC alongside the recognizable names of the period, by evaluating one example from the fascinating series of coins he produced.

The actual coin used in this article is a recent discovery from Britain that has inspired this piece. At first glance it would appear to most as an ordinary example of Republican coinage, displaying the personification of a goddess on the obverse with a symbol of Republican Rome on the reverse. In this case it depicts a quadriga (4-horse chariot); a symbol used on the earliest denarii of 211 BC. This traditional symbol twinned with a goddess here would not look out of place amongst those late 3rd century BC issues, were it not for the goddess depicted on our coin. The personification of Victoria with the legend S.C adorns the coin’s obverse, a symbolization therefore of a victory commemoration.

History does not record a triumph of the gens Carisia in 46 BC when this coin was struck, nor is there a documented history of the Carisian line before the mid 1st century BC. So it is unlikely this coin issue commemorates a family victory. It must therefore herald the victory of a contemporary event or figure - Julius Caesar. Such a conclusion should not be remarkable, considering Caesar had just been declared a dictator for ten years. He was therefore well-known, holding a position of direct and indirect influence over the coinage minted. Another known type of Titus Carisius depicts a cornucopia above a globe with a sceptre and rudder on either side (Crawford 464/3A). Such imagery evokes ideas of wealth and prosperity over the globe, with the rudder acting as a guide. This is comparable with Caesar’s accomplishments in annexing Gaul and forays to Britain in the previous decade.

Furthermore, connections between the quadriga-issue and a Caesarian triumph can be identified when Caesar’s own coin types are considered. It is widely accepted that Caesar continued his own coin production from his moving Spanish mint in 46 BC, striking types that reference his victory in the bello gallico of 58-50 BC (See RSC 13; Sydenham 1014; Crawford 468/1). Further links between the two can be found from an inscription (Figure 1) discovered in Avignon in 1841 believed to date from the third quarter of the 1st century BC (see Christol, M: Une nouvelle dédicace de T(itus) Carisius, praetor Volcarum, près d'Ugernum (Beaucaire, Gard) 2005 for more information). It briefly records a “Titus Carisius, son of Titus, Praetor of the Volcarum”, leading to speculation that Titus may have been the son of a soldier of the Volques tribe of Southern Gaul, granted Roman citizenship during Caesar’s time. This offers a potential explanation for a lack of records for a gens Carisia prior to the 1st century BC and even circumstantial evidence of historical connections between a character likely to be our moneyer and Caesar. Therefore it is by no means a stretch of the imagination to compare their coinages.

Figure 1: Avignon Inscription (Wikimedia Commons)

The reverse of our coin has similar Republican-themed imagery, with an unmistakable figure driving a quadriga with T.CARISI beneath in the exergue. Once more the personification of Victory appears, again suggesting that this coin’s message of victory is too forceful to be unintentional – hinting at the fusion of existing Republican iconography with contemporary Caesarian ideology. On reflection, this may provide the ultimate reason why ‘Titus Carisius’ has been virtually erased from history. The fact this coin type is so similar to many other Republican issues, as well as being loaded with Caesarian propaganda, aided Carisius’ disappearance. However one factor remains that explains how I am able to write such an article upon Carisius’ coinage - his name. The very fact that Titus Carisius ascribed his own coinage, a standard practice among Republican moneyers, gives us a small window into the dying days of the Republic, a time clearly dominated by the actions of one man and his heirs. Yet this coin offers more; it provides insight into the actions and presumably the aspirations of other forgotten members of the ruling classes. Does this coin, however subtly clouded in Caesarian propaganda, radiate a hope for the restoration of earlier Republican values by utilizing an established coin design, or does it simply confirm the acceptance of a dictator? However likely the latter is from the available evidence, the true meanings of the coin have unfortunately been lost to the passage of time. I am however certain of one thing… I’m glad he left us his name.

Written by Gregory Edmund, currently a 2nd Year Undergraduate studying Ancient History at the University of Warwick. His main interests lie in Republican Roman coinage (after 211BC) as well as Iron-Age and Roman Britain.

Written by Gregory Edmund, currently a 2nd Year Undergraduate studying Ancient History at the University of Warwick. His main interests lie in Republican Roman coinage (after 211BC) as well as Iron-Age and Roman Britain.

April 01, 2015

The coin that killed Caesar?

It is the 15th of March 44 BC, and as Julius Caesar sets forth from the threshold of his house to commence his journey to the Theatre of Pompey to convene with the Senate, he has no idea that he will not return later this day. Never would he have imagined that his life would come to such a brutal and bloody end at the hands of those he deemed so close to him. Indeed, as Plutarch informs us, the man was stabbed a total of 23 times by various senators, all so incredibly eager to partake in this momentous event in history that “many of the conspirators were wounded by one another, as they struggled to plant all those blows in one body” (Plutarch, Caesar, 66). To say that Caesar’s assassination was a veritable bloodbath would be a mere understatement. Well, what if I were to tell you that one of history’s most infamous murders could have been motivated by a single coin?

|

|

Denarius with portrait of Julius Caesar on the obverse (RRC 480/3)

|

In the very same year of Caesar’s assassination the moneyer P Sepullius Macer minted a silver Roman denarius with a portrait of Caesar on the obverse. Such a tradition was not new to the ancient world as demonstrated by earlier coins depicting the visage of Alexander the Great, however, there can be no doubt that this custom was new to Rome. And this is incredibly important because in doing so not only did he break with an important tradition, but more to the point, he dangerously associated himself with the trappings of a king. To the majority of us living in the modern world the concept of kingship is widely accepted but it is crucial to stress that for the Romans the term ‘king’ had acquired a seriously negative connotation by this point. In many ways, to associate one’s self with the trappings of a king was political suicide because of Rome’s inherent fear of too much power landing in the lap of one individual.

On the obverse of the coin the legend states “CAESAR DICT PERPETVO” meaning “Caesar, dictator for life” clearly suggesting that Caesar had arrived at a position of unrivalled power in which he undisputedly exerted a huge amount of control over Rome. Furthermore, the reverse of the coin depicting Venus holding Victory in her palm advocates an obvious message that Caesar is the man responsible for Roman peace and prosperity; he is of a higher status than any of his political rivals; he is the pinnacle of Roman greatness. One can’t help but wonder if this representation may have brought to mind for the political elite a concern that history might repeat itself culminating in the rebirth of another cruel King Tarquin.

It would also be worth considering that through the medium of coinage Caesar’s face would quite literally have been ‘in the face’ of his political enemies each and every day. Although the majority of Romans were illiterate and therefore unable to read the legend on the coin, they would still be affected by Caesar’s ‘propaganda’ because they could interpret the images and symbols. It is also worth remembering that there were numerous other suggestions of kingship including the curule chair that Caesar sat on in the senate, the fact that he was always allowed to state his opinion first, and that he gave the signal for the games to begin in the Circus.

On the other hand, it is important to consider the argument that the coin’s portrayal of Caesar was neither kingly nor divine and therefore it can be disregarded as a motivation for his assassination 44 BC. For instance, why would Brutus have followed in Caesar’s footsteps and placed his own portrait on the EID MAR coin (as seen below) in the following year if it was seen as unacceptable in the eyes of the Romans? If one of Brutus’ motivations to murder Caesar was that Julius Caesar was becoming more and more like a king then why would he, after killing him for that very reason, have portrayed himself in a kingly manner also? Moreover, Caesar’s veiled head on the obverse seemingly shows that he is supplicating the gods and therefore he is disassociating himself from the divine to show that he is mortal. This is further highlighted by the representation of his facial features like his sunken cheeks and pronounced Adam’s apple, which, in contrast to the eternally youthful appearance of gods, clearly show that he is human.

|

| Denarius of Brutus with his portrait on the obverse (RRC 508/3) |

Although the coin of Macer was clearly not the sole factor responsible for Julius Caesar’s famous demise, one can be sure that what it symbolises and represents must have played a pivotal role. In this respect, it seems only just to finish by saying that this object should be seen much more than simply a coin. It is an invaluable historical artefact that tells the story of how one man’s ambitions drove Brutus and Cassius along with the rest of the conspirators to take action and inadvertently set in motion a series of events that were to plunge the Roman Republic into more than a decade of civil war from which it would re-emerge as the Roman Empire.

This month's coin was chosen by George Heath. George is a first year undergraduate studying Classical Civilisation. He enjoys coin collecting and has a particular interest in early Republican coinage. He is also interested in the period surrounding Octavian's rise to power and the Augustan principate.

Images © The Trustees of the British Museum

March 01, 2015

Septimius Severus and his DI PATRII Coinage: A Tale of Two Identities

|

| Denarius of Septimius Severus (CNG Mail Bid Sale 73, lot 943) |

For the most part, research of the Roman concept of patria (definable as a complex embodiment of Roman collective identity) is dominated by the analysis of literary and epigraphic data. Offering a fresh perspective on this important concept is a single coin type, the only one from the Roman world in fact to bear the word patria in its legend outwith the imperial title pater patriae. Minted between AD 200 and 204 by the emperor Lucius Septimius Severus (emperor from AD 193-211) and his sons Geta and Caracalla in a variety of denominations, the obverse depicts (in this case) the bust of the emperor and bears the legend SEVERVS PIVS AVG. P.M. TR.P. XII (Severus Pious Augustus, Pontifex Maximus, holder of the Tribunician Power for the twelfth time). On the reverse are depicted two gods. Facing to the right is Liber Pater. In his hands he holds a cup and thyrsus (a wand or staff), and at his feet sits a panther. Facing to the left is Hercules, clearly identifiable by the club and lion skin. They are accompanied by the legend DI PATRII (gods of the patria).

In order to explain the significance of this coin type, three interpretations have so far been proposed, all of which rightly identify the coin type’s function as a visual representation of the emperor’s identity. Firstly, the German scholar Hasebroek has suggested that the coin could have been struck to commemorate Severus’ visit to Africa in AD 204, which would have included a stop off at the city of Lepcis Magna. Lepcis Magna was the patria of Severus, and its tutelary gods were Shadaphra and Melqart, the Lepcitanian equivalents respectively of Liber Pater and Hercules. However, this interpretation has recently been discarded due to the fact that evidence suggests Severus’ African tour took place in AD 207, three years after the latest issuing of the DI PATRII coin type. A second suggestion has been put forward by Barnes, who has argued that the coin was struck to commemorate the commencement and dedication of a temple to the gods Liber Pater and Hercules at Rome. However, very little physical evidence exists for us to be entirely sure that such a temple was constructed. Most recently, Rowan has expanded on Barnes’ argument, and has proposed that the coin marks the moment in which Liber Pater and Hercules became the di patrii of Rome.

So does the coin indicate the emperor’s Roman identity or his African origins? I would argue that the coin simultaneously represents both. Iconographically, the coin would appear to symbolise Severus’ African birthplace, and hence identity. As stated above, Liber Pater (Shadaphra) and Hercules (Melqart) were the tutelary deities of Lepcis Magna. This is indicated by several inscriptions from the city, their prominence in Lepcitanian sculpture and the fact that their temples occupied central locations within the old forum. It is also clear that the gods were important to Severus on a personal level, being also the tutelary deities of his regime, appearing in several other coin issues during his reign. Furthermore, whilst the joint appearance of Liber Pater and Hercules is identifiable in the coinage of Lepcis Magna from the first century BC to the first century AD, this is the first time that these gods appear together in any form on Roman coinage.

Iconographically, therefore, the coin seems to proudly display Severus’ Lepcitanian identity. Surely, therefore, the legend DI PATRII must correspond to them also, stressing their role as the tutelary gods of his African patria? A consideration of epigraphic and literary evidence would seem to question this argument. Epigraphically, the legend DI PATRII is one that is very rarely found outside of Rome or Italy. With regard to the inscriptions in Lepcis Magna that refer to Liber Pater and Hercules, only one describes them in this way. Their most common epigraphic description is instead either GENII COLONIAE (guardian deities of the colonia) or DIBVS LEPCIS MAGNAE (gods of Lecpis Magna). In literature also, the phrase di patrii appears to have been used almost exclusively in relation to the gods of Rome, particularly with regards to the penates that were according to legend brought to Italy from Troy by Aeneas. Consequently, the phrase is frequently identified in Virgil’s great ‘national’ epic The Aeneid. It is also prominent, to give only one further example, within the speeches of Cicero, an individual who places particular emphasis upon the fundamental relationship between res publica and patria in his writings.

This coin, therefore, can be seen to symbolise Severus’ local Lepcitanian identity alongside his that of his role as the cultural and religious leader of the Roman world. However, how do we contextually account for this apparent dual-identity? As stated above, this coin type was issued between AD 200 and 204. In AD 204, the Saecular Games were held. This event occurred every 110 years (although there was much flexibility in this) and marked the beginning of a new saeculum (era). The games were a moment in which to celebrate the continuation of Roman power and religious identity but they often contained elements of novelty reflecting the theme of a new beginning. Yet, exactly how does the coin fit into this context of tradition accompanied by novelty? The coin’s legend DI PATRII is clearly a nod to Roman tradition, since, as we have seen from the literary passages, it was a phrase that had important connotations to Roman collective identity. The iconography, however, indicates novelty. It is the first time that these two gods appear together on a single Roman coin, and they clearly stress the emperor’s pride in his native, and hence non-Roman, origins. It is true that other emperors also displayed personal deities on coinage during such events, but they did so with Roman religious iconography firmly in mind, and there is no indication that in doing so they are making a direct reference to their native origins, their local patriae. Thus, issued at a time which celebrated Romanitas, I would advocate the interpretation that Severus’ DI PATRII coinage is a wonderful statement of the equal importance that was placed upon local and imperial identities, proudly displaying the emperor’s attachment to his local patria, whilst also honouring the religious elements that were at the heart of Rome’s conceptualisation of patria.

This month's coin is contributed by Alexander Peck. Alex is currently a third year PhD student in the Department of Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick. His thesis examines the Roman concept of the patria. It considers the ways in which it was conceptualised by the Romans; how this conceptualisation changes over time; how the concept was institutionalised; and the concept’s role within Roman politics. He obtained his first degree, a first class MA (Hons) in Classics and Italian, from the University of Glasgow in 2012. He has a great interest in interdisciplinary collaboration on the subject of collective identity, especially on the question of the origins and evolution of nationalism. He is currently the editor for a forthcoming volume for Pickering and Chatto’s Warwick Series in the Humanities entitled Nationhood: From Antiquity to Modernity.

This month's coin is contributed by Alexander Peck. Alex is currently a third year PhD student in the Department of Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick. His thesis examines the Roman concept of the patria. It considers the ways in which it was conceptualised by the Romans; how this conceptualisation changes over time; how the concept was institutionalised; and the concept’s role within Roman politics. He obtained his first degree, a first class MA (Hons) in Classics and Italian, from the University of Glasgow in 2012. He has a great interest in interdisciplinary collaboration on the subject of collective identity, especially on the question of the origins and evolution of nationalism. He is currently the editor for a forthcoming volume for Pickering and Chatto’s Warwick Series in the Humanities entitled Nationhood: From Antiquity to Modernity.

Coin image reproduced courtesy of Classical Numismatic Group Inc., (Mail Bid Sale 73, lot 943) (www.cngcoins.com)

February 01, 2015

A coin of Gaius (Caligula)

Oderint, dum metuant: ‘let them hate as long as they fear’, a quote commonly accredited to the reign of the Emperor Gaius or Caligula (AD 37-41). Gaius is frequently seen as a manic Emperor. Some speculate his madness derived from epilepsy in a time that had no treatment for this illness, leaving Gaius in a constant state of panic and paranoia. He is accused of sleeping with other men's wives and bragging about killing for mere amusement, deliberately wasting money on his bridge, causing starvation, and wanting a statue of himself erected in the Temple of Jerusalem for his worship, despite the governor Petronius warning him there would be 'rivers of blood'. Once, at some games at which he was presiding, he ordered his guards to throw an entire section of the crowd into the arena during intermission to be eaten by animals because there were no criminals to be prosecuted and he was bored. The later sources of Suetonius and Cassius Dio provide additional tales of insanity. They accuse Caligula of incest with his sisters, Agrippina the Younger, Drusilla, and Livilla, and say he prostituted them to other men. They state he sent troops on illogical military exercises, turned the palace into a brothel, and, most famously, planned or promised to make his horse, Incitatus, a consul and actually appointed him a priest.

|

|

Sestertius of the emperor Caligula (RIC 1 36).

|

It seems hard to believe that one of the finest Julio-Claudian coins, with its exquisite detail, is from the reign of Caligula. The coin, shown above, suggests clever propagandizing. The reverse of this bronze sestertius, which was minted in Rome, depicts Caligula standing togate, whilst the attendants provide an insight into the attire of the early empire with one carrying an axe in his belt. The figure in the centre of the pediment of the temple wielding a spear and patera is likely Divus Augustus. On the left edge of pediment is either Mars or Romulus. On the right corner of the pediment is Aeneas, Ascanius and Anchises, a commonly reoccurring scene in art and architecture. This group communicated legitimacy through descent from Aeneas, fitting since Gaius’ rule was incredibly tenuous. The DIVO AVG clearly refers to the temple of Augustus. Interestingly the plan to build the temple of the deified Augustus was initiated by Tiberius in AD 20, but it was Caligula who opened and finally dedicated the building. The obverse displays pietas, veiled and draped, seated left, holding a patera in her right hand and resting her left arm on a small draped figure, which stands on a base.

This month's coin was selected by Alfred Wrigley. Alfred is a 1st year Ancient History and Classical Archaeology student who has a great interest in Julio-Claudian numismatics, with particular emphasis on Gaius.

January 01, 2015

A countermarked denarius of Vespasian from Spain

|

|

Denarius of Vespasian from Spain (RIC II2 no. 1340).

Countermark: GIC no. 839.

|

During the civil wars of AD 68-69 a number of mints operated in the western Roman empire in Spain and Gaul. They issued a series of anonymous silver and gold coins without names or portraits of the various contenders for power, and silver, gold and base metal coins in the names of the rival emperors Galba (AD 68-9), Vitellius (AD 69), and Vespasian (AD 69-79).

This coin is a silver denarius of Vespasian from one of those western mints, dated to the beginning of Vespasian’s reign, AD 69-70. The obverse has a left facing bust of Vespasian, together with his name and titles (IMP. CAESAR VESPASIANVS AVG.); the reverse has a figure of Victory on a globe, holding a wreath and palm branch, surrounded by the inscription VICTORIA IMP. VESPASIANI. In the recent second edition of the standard catalogue, RIC II, this coin type is assigned to an uncertain mint in Spain. Analyses confirm that the coins are made from Spanish silver, so an origin in the Iberian peninsula seems a reasonable assumption.

The real importance of this specimen lies not so much in its design or metallic composition, but in the fact that it was countermarked with a secondary stamp just in front of the emperor’s bust. The countermark consists of a rectangular incuse containing ligatured lettering that can be expanded to read IMP·VES. In other words, this is a countermark of Vespasian applied to a coin of Vespasian.

|

|

Close up of countermark

|

The IMP·VES countermark is found on other denarii ranging from Republican to imperial times. Most are found on Republican denarii. IMP·VES countermarks on coins of Vespasian himself are rare. Sometimes they have been found applied to denarii of Vespasian issued at Ephesus in western Asia Minor (modern Turkey) in AD 71-73 (for the examples, see Roman Coins and CNG coins). This gives us a terminus post quem of AD 73 for the episode of countermarking, which cannot have continued beyond the death of Vespasian in AD 79. A related countermark, with ligatured letters reading IMP. VES. AVG., is found on large silver coins called cistophori that seem to have circulated only in western Asia Minor (modern Turkey). It seems likely (but it has not yet been proved) that both the IMP·VES. and IMP. VES. AVG. countermarks were applied to coins in western Asia Minor, and perhaps at Ephesus itself, early in the reign of Vespasian. If so, it means that our specimen must have travelled from one end of the empire to the other not long after it was issued.

This is not the only western denarius with an IMP·VES. countermark. The web site http://www.romancoins.info/CMK-vespasian.html has a western denarius of Galba (AD 68-69) that bears the same mark. There is some evidence for quite rapid movement of denarii around the empire in this period. Western coins of the civil war of 68-69 from mints in Gaul turn up in an Italian hoard found at the port of Ostia, deposited in about AD 70, as does a denarius of the African usurper Clodius Macer (AD 68). The present coin conforms to that pattern of rapid interchange or movement of silver coins in the civil war and early Flavian period.

This month's coin was selected by Professor Kevin Butcher.He is currently completing work on a three-year AHRC-funded project in collaboration with Dr. Matthew Ponting of the University of Liverpool, investigating the metallurgy of Roman imperial and provincial silver coinages from Nero to Commodus, and will shortly begin work on the Cambridge Handbook to Roman Coinage. He is also interested in the application of social theories in archaeology, particularly with regard to material culture and the ancient economy. He has worked on several excavation projects in the Mediterranean and published the coin finds from several major ancient sites, including Nicopolis ad Istrum in Bulgaria and Beirut in Lebanon.

This month's coin was selected by Professor Kevin Butcher.He is currently completing work on a three-year AHRC-funded project in collaboration with Dr. Matthew Ponting of the University of Liverpool, investigating the metallurgy of Roman imperial and provincial silver coinages from Nero to Commodus, and will shortly begin work on the Cambridge Handbook to Roman Coinage. He is also interested in the application of social theories in archaeology, particularly with regard to material culture and the ancient economy. He has worked on several excavation projects in the Mediterranean and published the coin finds from several major ancient sites, including Nicopolis ad Istrum in Bulgaria and Beirut in Lebanon.

December 06, 2014

The festival of Saint Nicholas

December 6th, right after term ends, when students and teachers start relaxing, is Saint Nicholas’ day. This saint and bishop of Myra in Asia Minor (c. AD 270-343), famous as the patron of children and young people, is a worthy star for December’s coin of the month. Indeed, who does not know at least one of the legends related to his deeds?

|

Wooden bread stamp from Mount Athos, a gift to the author by G. Poupon from Saint-Maurice, who visited Mount Athos in 1982. Obverse: Ο ΑΓΙΟΣ ΝΙΚΟΛΑΟΣ with bust of Saint Nicholas — Reverse: square handle with Christogramm IΣ − XΣ / NI − KA.

One legend records Saint Nicholas resurrecting three boys cruelly murdered by a butcher who put them into barrels to sell them as ham. In another he saves three girls from prostitution. Their father was too poor to afford a dowry, and remaining unmarried, the daughters (without proper employment) may have had no other method to secure their incomes. Saint Nicholas provided the money by secretly placing three purses filled with coins in their house overnight; according to one version of the legend he dropped the money though the chimney and it fell into stockings. Therefore he is often depicted with three purses, and he became the patron of bankers as well. Other legends refer to the saint as offering assistance during distress at sea: therefore he is also the protector of sailors and of fishermen.

|

A Coptic icon with Saint Nicholas holding three purses.

Many generations have been told and will still tell the stories about Saint Nicholas. His generosity and care for children transformed him into Father Christmas, Santa Claus or simply ‘Santa’, who brings good things to children. He is probably one of the most popular saints. Although today’s western society has made him an icon of a commercial-style Christmas (starting earlier and earlier every year), other traditions keep Saint Nicholas’ stories alive. Thus sweets are put into stocks or into boots in remembrance of the legend about the three daughters. Artists commemorated the saint with amazing paintings, and composers with outstanding music. One piece of music I especially recommend is Benjamin Brittens’ Saint Nicholas cantata, here recorded with many lovely pictures taken of the saint and his legends.

Here we look at two contemporary depictions of Saint Nicholas on coin-like items. The first one is a wooden bread stamp from Mount Athos with a bearded bust of Saint Nicholas. He is dressed as a bishop of the Eastern Orthodox church with the omophorion (a garment similar to a stola) embroidered with four big crosses, holding a book and in the act of blessing. The saint is bareheaded, as he was shown in the Eastern, Byzantine world. The Greek legend Ο ΑΓΙΟΣ ΝΙΚΟΛΑΟΣ (‘The Saint Nicholas’) helps the viewer further to identify the saint. It is retrograde because the mould is a negative image. The mould has a reverse just like a coin: on the reverse is a handle inscribed IΣ − XΣ / NI − KA: ‘Jesus Christ is victorious’. This is a formula used in the holy communion of the Orthodox Church. Stamps with this formula are used to stamp bread for the Eucharist. This mould combines the christogram with Saint Nicholas’ bust. Both were used to stamp bread baked upon the occasion of his feast.

|

|

Music award of the Royal School of Church Music and emblem with Saint Nicholas blessing a child chorister.

In the Latin world, Saint Nicholas is represented as a western bishop with the mitre and pallium as shown on the second item, an almond-shaped medal. He is blessing a small figure kneeling in front of him and the inscription makes clear who the saint is (‘SAINT NICOLAS’). The legend also records that the medal is from the Royal School of Church Music. I initially wondered why this institution does not have Saint Caecilia on their medals. But the medals are awards originally designed for children choristers—therefore Saint Nicholas is a perfect design for the medal.

For Classicists it is noteworthy that Saint Nicholas is said to have destroyed Myra's renowned temple of Artemis and that his feast reaplced that of Artemis. A church was built over his tomb in Myra, and his relics are in many churches all over the world, creating new cults and new identities. In recent years Turkey has tried to claim them back for Myra.

|

This month’s coin was chosen by Suzanne Frey-Kupper, Associate Professor of Numismatics and Classical Archaeology at the Department of Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick. She works on Greek, Punic and Roman coinage from the Western Mediterranean and the North-Western provinces. She has published the coin finds from many major archaeological sites, including medieval and modern coins and medals. Living in Coventry since 2011, she is a member of the choir of Saint Barbara, Earlsdon.

Further reading:

Cioffari , G. (1987) San Nicola nella Critica Storia (Bari : Centro Studi Nicolaiani)

Galavaris, G. (1970) Bread and the Liturgy. The Symbolism of Early Christian and Byzantine Bread Stamps (Madison & London: The University of Wisconsin Press)

Travaini, L. (2013) ‘Coins as bread. Bread as coins’, Numismatic Chronicle 173, 2013: 187-200

November 01, 2014

Coining in Roman Britain Part 1: Before the Romans

This month the blog will run a series of posts about coinage in Britain, written by Dom Chorney. We kick the month off by looking at the coinage that existed in Britain before the Romans!

|

|

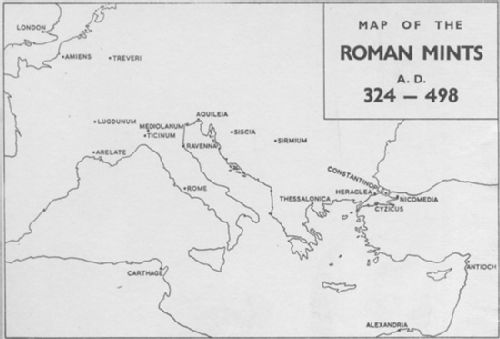

Map showing Rome's mints in the fourth century. |

The Romans didn’t just strike coins in their capitol, far from it. In fact by the 4th Century AD over a dozen official mints operated in the provinces of the empire, producing massive numbers of coins (see map). These mints tended to stem from provincial cities who struck their own coins in earlier periods of history, such as Alexandria in Egypt. Some however, were entirely new creations, in particular the mint at Londinum, modern day London. This series of posts will provide a very brief history on the subject of coin minting in Roman Britain, from the decades following the invasion in AD 43, to so called ‘decree’ of Honorius in AD 410, the date (though somewhat unreliable) believed by many to pinpoint the end of Britain as a Roman province.

Before the Romans: Celtic Coinage

|

|

Silver uninscribed stater struck in the south-west of Britain (50-20 BC). |

Despite the controversial use of the term ‘Celtic’, many scholars still refer to the coins minted in the last two centuries of Britain’s Iron Age as Celtic coins. The so called ‘tribes’ of Iron Age Britain struck coins, many deriving from gold staters produced in Greece by Philip II of Macedon, but with highly stylised designs. The iconography varies from region to region, but most Iron Age coins depict horses and stylized heads in a very abstract form. Through time, the coins of many Iron Age ‘tribes’ such as the Atrebates and the Catuvellauni become more Roman in style, indicating increasing contact with Rome. Some tribe’s coins show defiance, such as those minted in the South-West, where, rather than designs becoming more classical in nature, the coins become more abstract (see the coin pictured: coins like these are believed to indicate a strong refusal to adopt Roman style. Note the storngly stylised horse). Iron Age coins were minted in gold, silver and bronze, and are a complicated and highly theoretical topic in their own right. Mints of the Iceni (famously the tribe of the warrior queen, Boudicca) continued to produce coins in the years following the Roman invasion.

This month's coin series on Roman Britain is written by Dom Chorney, a young numismatist from Glastonbury, Somerset. He studied for his undergraduate degree at Cardiff (in archaeology), and achieved a 2:1. Dom is currently studying for an MA in Ancient Visual and Material Culture at the University of Warwick, and intends to undertake a doctorate in 2015. His main areas of interest are coin use in later Roman Britain, counterfeiting in antiquity, coins as site-finds, and the coinage of the Gallic Empire.

This month's coin series on Roman Britain is written by Dom Chorney, a young numismatist from Glastonbury, Somerset. He studied for his undergraduate degree at Cardiff (in archaeology), and achieved a 2:1. Dom is currently studying for an MA in Ancient Visual and Material Culture at the University of Warwick, and intends to undertake a doctorate in 2015. His main areas of interest are coin use in later Roman Britain, counterfeiting in antiquity, coins as site-finds, and the coinage of the Gallic Empire.

Image credits: Map from Late Roman Bronze Coinage, inside cover. Coin image from the Portable Antiquities Scheme, PAS IOW-035588.

Clare Rowan

Clare Rowan

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…