All entries for Friday 01 May 2020

May 01, 2020

Casting Roman tokens: Notes on two unpublished token moulds from Florence collections

Whilst the interest in token moulds has mostly been confined to excavation reports and occasional enquiries to date, recent scholarship is increasingly focusing on the value of these objects to better understand crucial aspects related to the manufacturing techniques, production location and use of tokens in antiquity (cf. Pardini et al. 2016; Rowan 2019). Lately, token moulds are also gaining attention on the market and in auction sales.

Two unpublished token moulds are presented below, which exist as part of two museum collections from Florence, Italy. Both token moulds are discussed in a study currently being undertaken by the author.

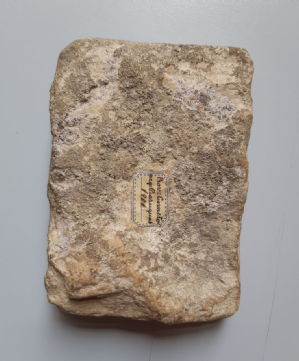

The token mould shown on Fig. 1 is held in the Museo Archeologico of Firenze (MAF) (inv. no. 79209). It is one half of a mould made of limestone, rectangular in shape, whose size is 115 x 80 x 27 mm. It would have been used in conjunction with the other half (now lost) in order to create 8 circular tokens of about 16-17mm in diameter.

|

|

Figure 1: Roman token mould from Museo Archeologico Nazionale of Firenze (MAF) (inv. no. 79209) (Courtesy of the MAF).

Based on the designs engraved on the surface – but some of them are unfortunately in poor condition – the resulting tokens carried at least three different types of images: on the left side, two of the preserved designs show Mars, helmeted, in military dress, standing right, holding spear in right hand and resting left on shield on ground (the type is also applied to Minerva, who is generally portrayed with a longer robe); on the top, two token cavities depict Mars helmeted, in military dress, standing right, holding spear in right hand and patera in left hand; in the lower right corner, a token design shows Hercules standing right, holding scyphum in left hand and club in right hand. These images are variants of types commonly depicted on Roman lead tokens, as already known through the examples published by M. Rostowzew as well as on individual catalogues of museum collections (for some of the types in question, see e.g. Rostowzew and Prou 1900, 135, fig. 32; Arzone and Marinello 2019, nos. 108-111 and 113). It is noteworthy that the first of the two images of Mars mentioned above appears on the tokens produced at the time of Nero, and was adopted on official coinage just afterwards, occurring on the coins issued during the Civil Wars of AD 68-69 (Fig. 2). However, the designs attested on the MAF mould are closer to the variant of a Mars type largely found on coinage from the time of Trajan (Fig. 3) up to the fourth century, which allows us at least to date the token mould to this broad time frame. To support this, morphological and stylistic features, as well as the material used, are consistent with the token molds from Rome and Ostia, generally assigned to the period between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD.

Figure 2: Silver denarius, RIC 12 Civil Wars 20, AD 68-69. (UBS Gold & Numismatics, Auction 83, lot 183).

|

|

Figure 3: Bronze As of Trajan, Rome AD 99-100 (= RIC II, Trajan 410), American Numismatic Society (inv. no. 0000.999.18549)

This token mould is said to have been found in Corneto Tarquinia (Lazio), whose ancient site was one of the most important settlements of the twelve Etruscan cities (the ‘Dodecapolis’), and which was under Roman domination since the third century BC. This place does not appear among the sites documented as find spots of token moulds to date, which have been found in Rome and Ostia, except for two examples from Como and Telesia (Rowan 2019, 98-99). If one accepts as reliable the information on its place of discovery, this mould specimen might suggest that a local production of lead tokens existed in Tarquinia in the imperial period. Moreover, it has recently been assumed that a ‘distributed production’ rather than a centralized single workshop was the common ‘model’ for the manufacture of tokens over the Roman period, which would have been created ‘in multiple places by multiple individuals’ (cf. Rowan 2019, 97).

This piece was sold to the MAF on 10 May 1901 by the collector and member of the Accademia Colombaria Anton Domenico Pierrugues, who donated his collection of Greek and Roman coins to the museum after his death (1915).

|

|

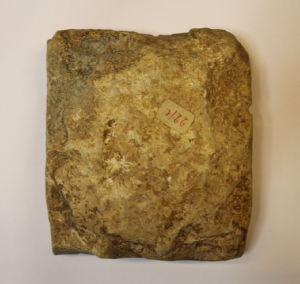

Figure 4:Roman token mould from Casa Buonarroti, Florence (Lenzini Moriondo’s inventory (1964), 22/1) (Courtesy of Casa Buonarroti).

Fig. 4 illustrates one half of a token mould housed at Casa Buonarroti, whose collection was formed from the 16th to the 19th century from the bequest of Michelangelo Buonarroti and his descendants. The piece is made of limestone, quadrangular in shape, and is 83 x 76 (min. 73) x 28 mm in size. The other half of the artefact is lost also in this case. The mould would have created seven circular tokens of 14-15 mm in diameter, which were decorated with the image of the Three Graces on one side. This depiction is a popular type on Roman lead tokens. A bronze uniface Roman token (14mm, 2.90g) showing the Three Graces on one side while blank on the other side exists as part of the Casa Buonarroti collection. The iconography and size of this token perfectly match the token cavities of the mould, making it likely that the bronze tessera was cast through the mould in question (Figs. 5-6). Anyway, it is likely that this bronze token was a product of a sample casting from the mould after its discovery. This might be suggested by the absence of remains of casting sprues on the token specimen as well as by its uniface appearance, since it is highly probable that the other half of the mould containing casting branches to the cavities was also decorated (see below). However, no data is available about the place of discovery of the mould, and it is not possible to determine when precisely in modern times the tessera was cast.

|

|

|

Figs. 5-6: AE Roman token (14mm, 2.90g), Casa Buonarroti, Florence.

The mould has a remarkable resemblance to a token mould of palombino marble with the same designs (105 x 75 mm for 7 circular tokens of ca. 17 mm) published by Cesano (1904, 11, fig. 1), which was found in the 19th century in Rome during the Lungotevere works. Such close ties might hint that the Casa Buonarroti mould came from Rome. According to ongoing research by the author, the mould may have been part of the inheritance of the antiquarian and senator Filippo Buonarroti (1661-1733), the great-grandnephew of Michelangelo Buonarroti, who stayed in Rome over the years ca. 1684-1699 serving as secretary, conservator of collections and librarian of the influential family of Cardinal Gasparo di Carpegna. In Rome, Filippo Buonarroti led a number of archaeological explorations which allowed him not only to assemble an impressive collection of Roman and Etruscan antiquities, but also to conduct pioneering studies in ancient iconography, epigraphy, and numismatics.

|

|

Figs. 7-8: Top and bottom sides of the mould from Casa Buonarroti, Florence.

Both token moulds show morphological and technical features which are largely documented for this class of objects. The extant half of the MAF mould shows a ‘herringbone’ arrangement, with a central casting channel with branches leading to the individual token moulds. The piece from Casa Buonarroti has instead only a central casting channel and no ‘branches’; one should assume that the now lost other half of the mould contained the channels through which molten lead was poured into the token cavities. In the top right and lower left corners, both molds bear the holes of the nails which were used to fasten both halves of the mould together, but also to ensure that they were correctly aligned (cf. Rowan 2019, 95). Furthermore, all four sides of the token mould from Casa Buonarroti carry small grooves which, as has been argued, would be suggestive of the use of wire which wrapped around the molds during the casting process (cf. Pardini et al. 2016) (Figs. 7-8). Also, as with a token mould from the Harvard Art Museums discussed by Rowan, a deep central hole is found in the center of each token cavity of the Casa Buonarroti mould, being visible in the guise of a protuberance on the body of one of the Graces in the resulting token, as is attested on the extant bronze tessera from Casa Buonarroti. This depression would be a clue of the method employed for engraving the token designs, since it would have been caused by the bit of a tool used for cutting the circular depressions before the designs were engraved. Finally, the back of both mold specimens is unworked, as attested on many moulds of this type.

Further analysis and the potential discovery of new specimens could help develop future discussion on the ancient token moulds, thus providing a more complete picture about the production and use of tokens in the ancient world.

|

This blog was written by Cristian Mondello as part of The creation of tokens in late antiquity. Religious ‘tolerance’ and ‘intolerance’ in the fourth and fifth centuries AD project, which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 840737.

Select bibliography

A. Arzone and A. Marinello, Museo di Castelvecchio. Lead Tokens. Tessere di piombo (Modena, 2019).

L. Cesano, ‘Matrici e tessere di piombo nel Museo Nazionale Romano’, NSc. (1904), 11-17.

G. Pardini, M. Piacentini, A.C. Felici, M.L. Santarelli, and S. Santucci, ‘Matrici per tessere plumbee dalle pendici nord-orientali del Palatino. Nota Preliminare’, in A.F. Ferrandes and G. Pardini (eds), Le regole del gioco. Tracce, archeologi, racconti. Studi in onore di Clementina Panella (Rome, 2016), 649-667.

U. Procacci, La Casa Buonarroti a Firenze (Firenze, 1965).

M. Rostowzew, Tesserarum urbis Romae et suburbi (St. Peterburg, 1903).

M. Rostowzew and M. Prou, Catalogue des plombs de l’antiquité (Paris, 1900).

C. Rowan, ‘A Roman token mould in Harvard’, Coins at Warwick Blog.

C. Rowan, ‘Lead token moulds from Rome and Ostia’, in N. Crisà, M. Gkikaki, and C. Rowan (eds), Tokens. Culture, Connections, Communities (London, 2019), 95-110.

Cult Development in Provincial Syria

|

|

Introduction

I will use the above coinage to briefly explore the developments of a Syrian cult and thus the relationship between local cults and Roman (military) presence in the eastern provinces.

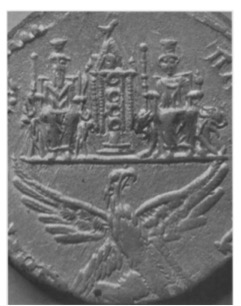

Pictured in fig.1 is a rare tetradrachm minted in the 3rd century AD under Caracalla. The tetradrachm may have been the principal unit of silver coinage used in Syria during this period, but the iconography on the reverse makes this coin intriguing. It is thought to depict cult statues belonging to the Temple of Ataragtis and Hadad (Syrian gods) at Hierapolis (Syria).

Cultic and Civic Context

The cult of Atargatis and Hadad was Syrian in origin and the sanctuary pre-dated Greek/Macedonian conquest. From Seleucid rule to the late third century AD Hierapolis was a provincial religious hub and mustering point for the Roman military. The Greek legend on a similar bronze coin under Severus Alexander (fig.2): ΘΕΟΙ CYRIAC IEPOΠΟΛΙΤΩΝ ‘the gods of Syria, (coin) of the Hieropolitans’ helps identify the figures represented on the Caracalla coin. Near-contemporary written accounts and artwork from Syria corroborate this.

|

|

Fig.2 Bronze coin of Hierapolis, minted under Severus Alexander (222-235 AD).

Obverse: Radiate bust of Severus Alexander right, AYT KAI MAP AYΡ CE - ΑΛΕΞΑΝΔΡΟC [CEB].

Reverse: Image of the Syrian gods of the Hierapolitans: Hadad left, seated on throne; Atargatis right, seated on throne; ensign between them. Below lion walking right; ΘΕΟΙ CYRIAC IEPOΠΟΛΙΤΩΝ.

Photo credit: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Münzkabinett.

|

It seems that a variety of peoples worshipped at this sanctuary, and thus the deities were attributed a variety of names and associated myths. The Greeks called Atargatis ‘Hera’ (and Aphrodite) and Hadad ‘Zeus’. Lucian, writing in the second century AD, describes the ionic temple with its cult statues of Atargatis and Hadad sitting on their thrones borne by lions and bulls respectively, as Caracalla’s coin depicts. These specific deities are further identified by their tall headdresses and attributed objects. Both deities hold sceptres in their left hands and Atargatis holds a spindle in her right hand, as Lucian describes. It is thought that Hadad may be holding either a thunderbolt or ear of corn in his right hand.

Between the cult statues themselves was an ensign, called a ‘semeion’. Its exact nature has been disputed. Lucian writes: ‘between both of these [statues] stands another golden statue. It does not have its own shape but bears the images of the other gods’. I agree with Darcus that here Lucian is likely referring to the images of Atargatis and Hadad (or some other ‘indigenous’ gods).

Roman Military Symbols and Indigenous Gods

The near identical ensigns on the coins comprise of hollow rings on staffs. Gabled pediments top them with doves at the summits. They bear a clear resemblance to Roman military standards. Another similar standard in the same iconographical context can be seen in a relief from fellow Syrian city, Dura-Europos (fig.3). The relief depicts a specific type of military standard with cloth banners called a ‘vexillum’. Based on other archaeological evidence Dura has yielded, this vexillum type seems to have been the most common there. The same vexillum has been identified by some scholars on the coins of Caracalla and Severus.

|

|

Fig.3 Relief from Dura-Europos,

second or third century AD.

On the left Hadad; the right Atargatis;

between them the ‘semeion’.

Photo credit: Yale University Art Gallery.

|

There is evidence that Roman military standards were housed in shrines in provincial Syria. It seems that in the imperial period these standards possessed their own spirit/sacred powers, offering protection and symbolising the strength of the Roman Empire. Ergo, they were an expression of military ideology and collective identity. The ethnic composition of the army in Syria would have been diverse, with local recruitment having been initiated the previous century. Although the extent to which the Roman military interacted with civilians in provincial Syria is uncertain, it is well known that the Roman military acted as a primary vehicle in the process of cult mobility in imperial times. Thus the cult of Atargatis itself disseminated across the empire: throughout Syria, northern Mesopotamia, the Mediterranean and even made it to Britain.

Fergus Millar noted that the absence of the ensign on earlier coins under Trajan supports the suggestion that the ensign was a later addition to the temple. If there had been a permanent Roman military standard in the temple, it was likely not the ensign Lucian saw. Instead Lucian describes a more indigenous religious ensign, very similar to motifs seen on Syrian cylinder seals dating back to the second millennia BC: staffs bearing the heads of deities with birds on top.

At the bottom of the reverse, an eagle with a lion walking below it can be seen. The exact meanings of these symbols in this context are uncertain. It is possible that this is a visual hierarchy reinforcing imperial positions, a common practice in the provinces: Rome on top, symbolised by Jupiter’s eagle and Hierapolis/Syria below, by a lion of Atargatis. However, the presence of the eagle on Syrian coinage has been traced back to before Roman conquest and on other Syrian coinage the eagle is thought to allude to local myth and history.

Commissioner and Audience?

Knowing the commissioner and audience of a coin helps greatly in attempting to identify the potential meanings of such symbols. Based on the metallurgical composition and style of the Caracalla coin, it has been suggested that it was minted in Rome but it could also have been minted in Syria. Regardless, the coinage almost certainly represents deliberate choices made by the elite, meaning that the imagery could reflect social attitudes of the inhabitants of Hierapolis, attempt to modify them, or even ignore them (although the latter is unlikely).

Additionally, without knowing the circulation of this coinage, it is difficult to say the extent to which the messages were intended for the local community and ‘outsiders’, although in most cases it was predominantly for the former. The Caracalla coin likely only circulated locally, but like many Syrian cities, the inhabitants of Hierapolis would have been culturally diverse. Furthermore, people throughout Syria and other provinces visited and sponsored the cult, so if they had seen this coinage it likely would have resonated with them too, evoking a sense of collective Syrian identity. This may have also been the case for people who were familiar with a similar image, for example the Dura relief.

As for the Roman military present in this area, would they have seen this coinage? Such locally issued silver coinage was used for army pay. Would the juxtaposing of a military standard with the Syrian gods have created a sense of collective identity and unity for soldiers and civilians? Or in this context had the traditionally Roman symbol been transformed into a distinctly local one?

Conclusion

The analysis of this coinage has shown the development of the cultic identity of Hierapolis (Syria). When a Roman military symbol was placed in the local temple context, ‘Romanness’ would have become a part, not just of the religion, but also the local myth and history surrounding the cult. Even if a Roman military standard were not housed in the temple, the desire to express it as such existed and was on public display through this coinage. Thus, Hierapolis reconciled their civic identity with the Roman presence in their society, exhibiting their place in the empire.

This month’s coin of the month was written by Nicholas Aherne. Nicholas studied Classical Civilisation at Warwick and graduated in 2019. He is planning to undertake a Masters in 2020. His current research concerns the interactions between Greco-Roman culture and indigenous cultures in the Hellenistic and Imperial Periods, with particular focus on religion.

Bibliography

Lucian, De Dea Syria, (Perseus)

Darcus, R. (1967) A new translation of Lucian’s De Dea Syria with a discussion of the cult at Hierapolis, MA thesis (Vancouver: University of British Columbia)

Strong, H.A. (1913) The Syrian Goddess: Being a translation of Lucian’s ‘De Dea Syria’ with a life of Lucian, ed. with notes and introduction by Garstang, J. (London: Constable and Company)

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, trans. John Bostock (London: Taylor and Francis : 1855) (Perseus)

Strabo, Geography, trans. H.C. Hamilton (London: George Bell & Sons: 1903) (Perseus)

Andrade, N.J. (2013) Syrian Identity in the Greco-Roman World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Billing, J. The Military Standards of the Roman Legions: Symbolic objects of ideology, veneration and belief https://www.academia.edu/8640103/The_Military_Standards_of_the_Roman_Legions_Symbolic_objects_of_ideology_veneration_and_belief

Butcher, K. (2005) ‘Information, legitimation, or self-legitimation? Popular and elite designs on the coin types of Syria’ in Coinage and Identity in the Roman Provinces eds. C. Howgego, V. Heuchert, and A. Burnett (Oxford: Oxford University Press) 143-162

Butcher, K. (2004) Coinage in Roman Syria: Northern Syria, 64 BC-AD 253 (London: Royal Numismatic Society)

Butcher, K. (2007) ‘Two Syrian Deities’, Syria 84: 277-285

Butcher, K. and Ponting, M. (1995) ‘Rome and the East: Production of Roman Provincial Silver Coinage for Caesarea in Cappadocia under Vespasian’, Oxford Journal of Archaeology 14: 63-78

Erdkamp, P. (2007) A Companion to the Roman Army (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing)

Howgego, C. (2005) ‘Coinage and Identity in the Roman Provinces’ in Coinage and Identity in the Roman Provinces eds. C. Howgego, V. Heuchert, and A. Burnett (Oxford: Oxford University Press) 1-18

James, S. (2019) The Roman military base at Dura-Europos, Syria: an archaeological visualization (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Kaizer, T. (2013) 'Identifying the divine in the Roman Near East' in Panthée: religious transformations in the Graeco-Roman Empire eds. L. Bricualt and C. Bonnet, in Religions in the Graeco-Roman world V. 177 (Boston: Brill) 113-130

Meadows, A.R. (1998) ‘The Mars/eagle and thunderbolt gold and Ptolemaic involvement in the Second Punic War’ in Coins of Macedonia and Rome: Essays in Honour of Charles Hersh eds. A. Burnett and U. Wartenberg (London: Spink)

Price, S. (2012) ‘Religious Mobility in the Roman Empire’, The Journal of Roman Studies 102: 1-19

Weiss, P. (2005) ‘The Cities and their Money’ in Coinage and Identity in the Roman Provinces eds. C. Howgego, V. Heuchert, and A. Burnett (Oxford: Oxford University Press) 57-71

Williamson, G. (2005) ‘Aspects of Identity’ in Coinage and Identity in the Roman Provinces eds. C. Howgego, V. Heuchert, and A. Burnett (Oxford: Oxford University Press) 19-28

Wimber, K. Michelle (2007) Four Greco-Roman Era Temples of Near Eastern Fertility Goddesses: An Analysis of Architectural Tradition, MA Thesis (Provo: Brigham Young University)

Clare Rowan

Clare Rowan

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…