It’s all fun and games in the gymnasium of Ancient Messene, by Matthew Evans

|

|

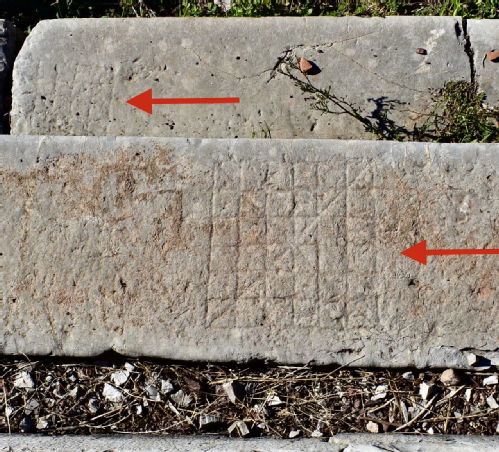

Incised gaming boards in the gymnasium of Messene on the interior steps of the propylon (left) and the benches of the palaistra’s exedra (right). (Author's own photographs). |

Pictured here are three incised gaming boards found in the stadium-gymnasium complex of the city of Messene in southern Greece. The two best preserved of the three boards each consist of a square (ca. 27cm on each side) neatly separated into six columns and six rows of smaller squares; two diagonal lines then form a cross through the board. The third board is slightly smaller (ca. 15 cm on each side) and is in a poorer state of preservation though it seems to follow the same basic design.

|

Aerial image of the stadium-gymnasium complex at Messene showing the location of the incised gaming boards (Google Earth 7.3.3 2020, Archaia Messene Gymnasium, 37˚10’21”N 21˚55’08”E, elevation 767m, 2D map, viewed 28 April 2021). |

The complex, built in the late third century BCE and used until ca. 360/370 CE, is situated in the south of Messene and consists of a stadium with stone seating, surrounded by Doric colonnades on the east, north and west sides; the city wall provides a limit to the south. A palaistra (wrestling-school) is situated through the stadium’s west colonnade, suggesting that the complex functioned as a gymnasium (a place of athletic training and education) at least when athletic games were not being held in the stadium. Access to the complex was provided by a monumental Doric propylon (gateway) in the north-west corner, built in the Augustan period (late first century BCE to early first century CE), and it is on the surface of its interior steps that two of the gaming boards were discovered. The third was found in the palaistra, specifically on the surface of a stone bench located in an exedra (a hall with seating and a wide, columned-opening) on the building’s west wing.

A two-player strategy game not dissimilar to modern chess would have been played on these incised gaming boards, each player using an equal number of coloured pieces or pessoí (πεσσοί). Greek literary sources such as Plato (The Republic, 6.487d), Polybius (Histories, I.84) and Julius Pollux (Onomasticon, 9.97) causally reference these types of games using various names including petteia, pessoí, psêphoi (all three names meaning pebbles), pente grammaí (five lines) and poleis (cities). According to Plato, these games originated in Egypt before being adopted by the Greeks (Phaedrus 247d). In the Latin sources, the most well-known game of this type is called ludus latrunculorum or latrunculi (meaning the game of brigands or mercenaries) which is a variation of the earlier Greek games, referenced by Varro (On the Latin Language, X.22) and Ovid (The Art of Love, ll. 357-360; Tristia, ll. 479-481) among others (see the anonymous poem Panegyric on Piso, ll. 190-208). The precise rules of these different games are not clear in the literary sources, though they all seem to be based on military tactics: a player captures the opponent’s pieces by trapping an enemy piece between two pieces of his own. The pieces can only move vertically and horizontally though it is uncertain whether or not movements are restricted to one square per move; for the purposes of the game, it at least seems unlikely that a piece is able to land on, or jump over, another. The game is won when an opponent is left with a single piece.

Similar incised gaming boards have been discovered in various forms and places across the ancient world, from the steps of the Basilica Julia in the Roman Forum to the numerous examples in the agora (marketplace) and streets of Ephesus in Asia Minor. Glass game pieces and the metal hinges of a wooden game board were even discovered in a mid-first-century CE grave in Stanway, Essex near Colchester, though there has been scholarly debate about whether these were used for latrunculi or a variant of the Celtic game called fidchell or gwyddbwyll. The incised examples from Messene and elsewhere, in any case, demonstrate that certain public places in ancient cities were often the settings of informal games among friends or those passing the time together.

The findspots of the gaming boards in Messene can inform us about the uses of these spaces within the gymnasium. The example on the bench in the palaistra is interesting since current scholarship strictly associates the type of room (exedra) where it appears with intellectual lessons, following the account of Vitruvius (On Architecture, 5.11). The gaming board here, however, indicates that the room was also used for relaxing and as a space in which people could spend their spare time with their friends. This is also supported by Plato’s description of youths playing a game of odd-and-even (ἀρτιάζω) in the corner of an Athenian palaistra’s changing room (apodyterion), a room apparently similar to this exedra at Messene. The examples on the steps are more informal in their setting, located at the entrance of the complex. Why would someone stop here on the steps, in the main circulation space of the complex, to play a game on these incised boards? The Basilica Julia gameboards, which are also located on the steps, are at least out of the way of circulation points and enjoy a good view over the Forum. Perhaps at Messene, this shaded spot under the propylon was the perfect place to relax and play games when athletic events were taking place in the stadium or perhaps it was a good place to hang around with your friends on the way in/out of the complex.

Finally, the association between the type of games played on these incised boards and their setting is significant. The gymnasium of Messene was the place where citizen youths and men would come each day to train in athletics and to receive a formal paramilitary/athletic education as part of the ephebeia, a two-year military service of 18 to 20-year-old citizens. The possible games outlined above, whether the Greek petteia or Roman latrunculi, were military in nature and followed basic battle tactics. Such games, therefore, would have been particularly suitable for the ephebes (those taking part in the ephebeia) who were receiving their military education in these spaces, allowing them to put their newly acquired tactical skills and knowledge to the test against their peers, (check)mates and future comrades on the battlefield.

If you want try your own hand at latrunculi, you can play an online version at: https://locusludi.unifr.ch/ludus-latrunculorum/

Bibliography:

Austin, R.G. (1934). Roman Board Game I. Greece & Rome, 4.10, 24-34.

Austin, R.G. (1940). Greek Board-Games. Antiquity, 14, 257-271.

Kurke, L. (1999). Ancient Greek board games and how to play them. Classical Philology, 94, 247-267.

Lamer, H. 1927. Lusoria tabula. Realencyclopädie, 13.2, 1900-2029.

Locus Ludi (Accessed 28.04.2021). Inside Ephesus. https://locusludi.ch/inside-ephesus/

Schädler, U. (1994). Latrunculi – ein verlorenes strategisches Brettspiel der Römer. Homo ludens: der spielende Mensch, 4, 47-67.

Schädler, U. (2007). The doctor’s game – new light on the history of ancient board games. In P. Crummy, Benfield, S., Crummy, N., Rigby, V. and Shimmin, D. (Eds.), Stanway: an elite burial site at Camulodunum. London: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. 359-375.

Themelis, P.G. (1995 [1998]). Ἀνασκαφὴ Μεσσήνης. Πρακτικά της Ακαδημίας Αθηνών, 150, 55-86, πίν. 13-42. For the gaming boards, see p. 73.

Themelis, P.G. (1998/1999). Die Statuenfunde aus dem Gymnasion von Messene. Nürnberger Blätter zur Archäologie, 15, 59-84.

Themelis, P.G. (2001). Roman Messene: The Gymnasium. In O. Salomies (Ed.), The Greek East in the Roman context: Proceedings of a Colloquium Organised by the Finnish Institute at Athens, May 21 and 22, 1999 (pp. 119-126). Helsinki: Bookstore Tiedekirja. For the gaming boards, see p. 122.

|

This post was written by Matthew Evans, a PhD Candidate in the Department of Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick. Matthew’s research focuses on gymnasia in Greece and Asia Minor between the Hellenistic and Imperial periods, seeking to understand how space (architecture, statues, inscriptions) mediates the interrelationships between these complexes and cities/society. |

Jacqui Butler

Jacqui Butler

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…