All 1 entries tagged Altar;

No other Warwick Blogs use the tag Altar; on entries | View entries tagged Altar; at Technorati | There are no images tagged Altar; on this blog

January 19, 2021

Fortuna and a legate's wife in Roman Britain – by Jacqui Butler

|

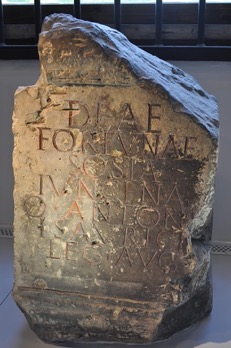

Altar/statue base dedicated to Fortuna by Sosia Juncina, York Museums Trust, museum number YORYM: 2007.6194. Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0. |

This freestanding stone, measuring approximately 381 x 655 cm, records a dedication to the Roman goddess Fortuna, and is currently on display in the Yorkshire Museum. Dating to the mid-second century AD, it is constructed from magnesium limestone and would either have been used as a votive altar or statue base. There is some damage to the top and side of the stone as can be seen in the image, and it was removed from its original context and reused as a building stone in later centuries. The lettering of the first two lines of the inscription is slightly larger in height, measuring 50mm, than the remainder of the lettering, which measures 45mm. The inscription (RIB644) reads and translates as follows:

Deae | Fortunae | Sosia | Iuncina | Q(uinti) Antoni | Isaurici | leg(ati) Aug(usti)

To the goddess Fortune Sosia Juncina, (wife) of Quintus Antonius Isauricus, imperial (legionary) legate, (set this up).

The dedication is interesting for the socio-cultural information it reveals, especially as there are only a relatively small number of extant altars with female dedicants in Roman Britain. These provide important evidence that women dedicated altars in a similar way to men, independently choosing the deities they addressed. There are at least two other extant altars dedicated by women in Roman Britain to Fortuna in different guises, and this may suggest that the personification of this Roman virtue could possibly have had some specific appeal to women. This is plausible given that Fortuna was favoured in Roman Britain for luck-bringing to dice games, but also as an apotropaic force in both military and bathing contexts, and she was also further associated with state or imperial power.

The altar was found in the locale of the public bathhouse, and it has been suggested that this indicated separate gendered baths. However, as there is no direct evidence of this, it seems more likely that the intention behind the dedication was an appeal for protection, due to the vulnerability entailed by being in a state of undress in the bathing context. Equally, the dedication may also have been intended to reflect state power, or even the protection of imperial property. The inscription appears to support this interpretation, as it identifies Sosia Juncina as the “wife of Quintus Antonius Isauricus, imperial legate”. It also demonstrates her status via that of her husband: Isauricus had command of the Sixth Legion and was suffect consul around 143 AD. However, it is also possible that Sosia Juncina was related to the family of Quintus Sosius Senecio, who was Roman consul in 99 and 107 AD, which would further establish her within the ruling Roman elite, and indeed independently of Isauricus. If this is correct, then it is feasible that she travelled with Isauricus to Britain, from Italy, and therefore the dedication can be further understood in several ways: it functioned to both promote and display her own personal identity, but also ideas of continuity and stability via Roman cultural and religious norms, which were significant in such a remote province. Identifying herself via Isauricus, also evidences another Roman cultural norm, that of female status and identity being derived from male relatives. However, it is important to note that although altar dedications certainly functioned to project personal identity, this was undoubtedly subordinate to their central role as prayers; Sosia Juncina’s dedication would either have resulted from asking or receiving divine intervention from Fortuna or was part of a ritual of request.

Lastly, it is interesting to note that the inscription appears to foreground DEAE andFORTUNAEwith the slightly larger height lettering. This visual emphasis on the deity’s name may reflect the connotations of the location of the altar/statue base within the bathing context, or equally it may have been intended to highlight Sosia Juncina’s claim on a relationship with Fortuna, whilst simultaneously memorialising it for posterity. Regardless, the altar/statue base clearly evidences female religious participation which is similar to male dedications in a public context, and the ability to commission and dedicate in this way, suggests some level of female autonomy within the religious sphere.

|

This post was written by Jacqui Butler, part-time M/Phil/PhD candidate in the Department of Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick. Jacqui’s research interests are in the depiction of both mythical and real women in the Roman world, and more specifically how they are represented in art. |

Bibliography

RIB644, Roman Inscriptions of Britain, Volume 1. Online at: https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/644

York Museum Trust. Online at: https://www.yorkmuseumstrust.org.uk/collections/search/item/?id=11543

Aldhouse-Green, M. (2018) Sacred Brittania, The Gods and Rituals of Roman Britain(London, Thames and Hudson).

Birley, A. R. (2005) The Roman Government of Britain (Oxford, Oxford University Press).

Campbell, J. B. (2012) “Sosius (RE 11) Senecio, Quintus” in The Oxford Classical Dictionary(4 ed.), eds. S. Hornblower, A. Spawforth and E. Eidinow, (Oxford, Oxford University Press).

Cooley, A.E. (2012) The Cambridge Manual of Latin Epigraphy(Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

Henig, M. (1995) Religion in Roman Britain, (London, B.T. Batsford Limited).

Hope, V.M. (2016) “Inscriptions and Identity” in The Oxford Handbook of Roman Britain, eds. M. Millett, L. Revell and A. Moore, (Oxford, Oxford University Press).

Parker, A. (2019) Assistant Curator of Archaeology, York Museums Trust. Information from private correspondence in March 2019.

Rives, J. B. (2007) Religion in the Roman Empire(Oxford, Blackwell Publishing).

Royal Commission on Historical Monuments of England, An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 1, Eburacum, Roman York(London, 1962).

Tomlin, R.S.O. (2018) Brittania Romana, Roman Inscriptions and Roman Britain(Oxford, Oxbow Books).

Woolf, G. (1996) “Monumental Writing and the Expansion of Roman Society in the Early Empire”, Journal of Roman Studies, Volume 86, pp.22-39.

Matthew Evans

Matthew Evans

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…