All 2 entries tagged Material;

No other Warwick Blogs use the tag Material; on entries | View entries tagged Material; at Technorati | There are no images tagged Material; on this blog

March 28, 2021

The Monarchy and Magic at Nimrud, by Emily Porter–Elliot

|

Relief panel from Nimrud, Iraq. (229.9 x 187 x 5.7 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art No. 31.72.3. OA Public Domain. |

This relief panel is from Northwest Palace at Nimrud, which is situated in modern day Iraq. Nimrud was a monumental site of various palaces and temples, with the most magnificent and perhaps the best understood archaeological remains, being that of the Northwest Palace, built by Ashurbanipal II (883-859 BC). The palace was decorated with an elaborate series of reliefs which boasted of the achievements and power of the Assyrian state. The panel was originally acquired by H. C. Rawlinson who gifted it to William Frederick Williams in 1854. The panel eventually ended up in the care of Union College, who sold it to C.E. Wells for J.D. Rockefeller. It was eventually gifted to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1931 by J.D. Rockefeller, where it is now on display along with other Assyrian antiquities in Gallery 401.

The panel portrays a winged supernatural figure, which faces left, and has the head of an eagle with a male human body. These figures appear throughout the palace in a series of reliefs which were originally painted in vivid colours, but these pigments have sadly not survived. The figures are representative of the supernatural population rather than representing divine beings and are slightly different in form with some being human-headed and others eagle-headed figures. They appeared in the doorways and in close proximity to the throne room. Figurines were commonly buried under doorways for protection in this period and had some similarities to the ones in the Northwest Palace relief scenes. The figures, therefore, have complex meaning and significance and there has been much speculation about the symbolism contained within the relief series.

What the figure holds has been highly contested. The object in its right hand has been thought to be a purifier, but others have argued that it is in fact a bucket. The object in the left hand has proved more puzzling but is thought to be a cone, representative of a special implement used by Mesopotamian farmers in a ritual action whereby the date-palm tree was fertilised. This tree is thought to be representative of prosperity and alludes to the idea of protecting the Assyrian state. The figures’ presence within the palace hints at the extent to which the king has gone to ensure the state is protected. The figure is elaborately dressed and bedecked in jewellery which makes references to divinity and was ostentatious in its design.

These relief panels are unique in that they contain an inscription which cuts across the imagery. This inscription runs throughout the entire relief series, often in the middle of the image. The inscription was in cuneiform script and written in Akkadian, although it is unlikely that many people who frequented the palace would have been able to actually read the inscription, they would have been aware of its significant and powerful presence. The inscription details the achievements of Ashurbanipal II, and discusses the heritage and royal titles of Ashurbanipal, before detailing his extensive military and building campaigns. It has been suggested the inscription was also used in the palatial decoration, as it had magical connotations and contributed to the protection of the palace, king and more widely the Assyrian state.

Bibliography:

Cline, E. and Graham, M.W. (2011) Ancient Empires from Mesopotamia to the Rise of Islam. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crawford, V.E and Harper, P. O and Pittman, H. (1980) Assyrian Reliefs and Ivories in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Palace Reliefs of Assurnasirpal II and Ivory Carvings from Nimrud. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. Relief Panel- https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/322595 (2021) Accessed 14th March 2021.

Seymour, M. Nimrud- https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/nimr_1/hd_nimr_1.htm (November 2016) Accessed 14th March 2021.

|

This post was written by Emily Porter-Elliot, who is currently studying for an MA in Ancient Visual and Material Culture at the University of Warwick. Emily did her undergraduate studies in Archaeology at Cardiff University. Emily’s research interests are in museums and their collection histories and is especially interested in how museums sometimes controversially display artefacts. |

February 24, 2021

Limestone Herakles from Nineveh, by Robert Schoenell

|

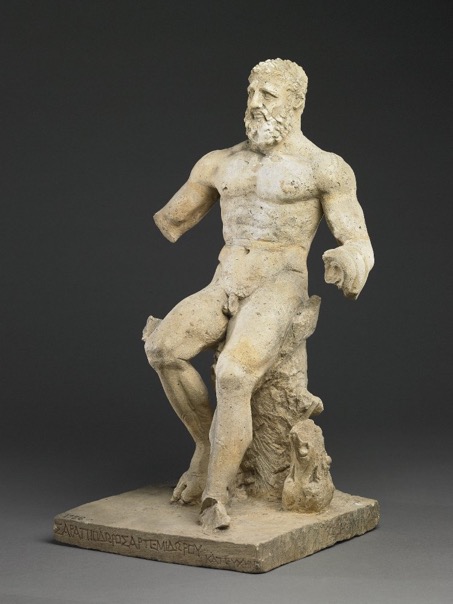

Limestone statue of Herakles from Nineveh, Iraq. Height: 52.9 cm. British Museum No.1881,0701.1.Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0. |

This limestone statue of Herakles was discovered in Nineveh, Iraq in 1880 and is on display in the British Museum. Herakles is aligned facing the front of the plinth and is depicted as a bearded man, seated on a rock, using the skin of the Nemean lion as a cushion. His left hand originally held a club, the top of which is still visible on the plinth, and in his right hand he held a drinking vessel, like a skyphos or a kylix. Herakles has a ribbon wrapped around his head, with his eyes being carefully designed with an incision on the eyeball, indicating the iris and a drilled hole for the pupil. Stylistic and typological analysis of the statue make a dating to the 2nd century AD very likely.

Two Greek inscriptions are present on the plinth. The larger and more prominent of the two is on the front of the pedestal and reads:

‘ΣΑΡΑΠΙΔΟΡΟΣ ΑΡΤΕΜΙΔΩΡΟΥ ΚΑΤ’ ΕΥΚΗΝ’

‘Sarapiodorus son of Artemidorus (dedicated this) in fulfilment of a vow’

A small inscription on the left side of the plinth reads:

‘ΔΙΟΓΕΝΗΣ ΕΠΟΙΕΙ’

‘Diogenes made (this)’

Traces of red paint are visible in the cut letters of the inscription which increased the visibility of the inscription.

This statue was a votive offering to Herakles, the son of Zeus, famous for his twelve labours, who was worshiped for his outstanding strength and courage. Other Greek gods were present in the city of Nineveh as well, for example there is another limestone figure which is of Hermes on display in the National Museum of Bagdad.

Artemidorus and Diogenes are common Greek names that are not unusual in a well-connected city like Nineveh. The name Sarapiodorus has a strong connection to the god Sarapis and Ptolemaic Egypt. Nineveh was abandoned after the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 609 BC. The city was resettled under the Seleucid Empire, beginning in the 3rd century BC, and later by the Parthian Empire. It was then taken by a claimant to the Parthian throne, who was supported by Rome in 50 AD, and this opened the city to trade relations throughout the Greco-Roman world.

The statue has been identified as a copy of the Herakles Epitrapezios (Epitrapezios meaning ‘on the table’). The Epitrapezios is mentioned by Martial, in the Epigrams 9.43-44,and Statius, in the Silvae 4.6,who describe a small bronze statue in the possession of the wealthy Roman, Novius Vindex. According to Martial and Statius, the Herakles Epitrapezios was made by the famous sculptor Lysippus, for Alexander the Great (356-323 BC). It was a small table decoration, depicting the wine drinking Herakles seated on a rock, holding the club in one hand and a drinking vessel in his other. The statue accompanied Alexander on his conquest and was later in the possession of Hannibal Barka and Sulla, before finding its way into the collection of Novius Vindex.

The stylistic and typological features present in the Herakles from Nineveh are a striking example of a Roman adaptation of a Hellenistic statuary type. The frontal orientationand the incision indicating the iris are also present in 2nd century AD depictions of Herakles in Rome. The ribbon used as a headband for the Nineveh Herakles is present in depictions of Hercules on a Hadrianic relief tondo, used as a spolia for the Arch of Constantine and on a Hadrianic aureus coin.

The Nineveh Herakles was not only influenced by Roman but by local workshop traditions. The stylistic features in this statue are very similar to that present in other sculptures from the region, especially to the limestone statues from Hatra. The statue is, therefore, the result of a Roman adaptation of a popular Hellenistic statuary type, heavily influenced by the local workshop traditions of Mesopotamia.

|

This post was written by Robert Schönell who is currently participating in an Erasmus exchange and is studying Ancient Visual and Material Culture at the University of Warwick as part of his Masters studies in Classical Archaeology at Freie Universität Berlin. Robert did his undergraduate studies in Archaeology at Universität zu Köln, Cologne. Robert's research interests are sculpture and iconography, and he is especially interested in Hellenistic art and how it was copied and reinterpreted by Roman artists. |

Bibliography:

British Museum. Online at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1881-0701-1

Bartman, E. (1992) Ancient Sculptural Copies in Miniature(Columbia Studies in the Classical Tradition 19) (New York, E.J. Brill).

Invernizzi, A. (1989) ‘L'Héraclès Epitrapezios de Ninive’, in: Archaeologia iranica et orientalis: miscellanea in honorem Louis Vanden Berghe, eds L. vanden Berghe, L. de Meyer, E. Haerinck (Gent: Peeters) pp. 623-636.

Reade, J. E. (1998) ‘Greco-Parthian Nineveh’, Iraq 60, pp. 65-83.

Matthew Evans

Matthew Evans

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…