Hair today, gone tomorrow: imperial trendsetters, by Tallulah George

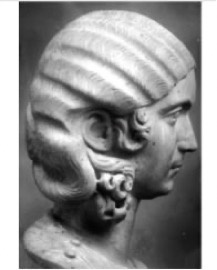

This detachable marble wig piece from the second or third century CE (Figure 1) perfectly captures the zeitgeist of upper-class female life in imperial Rome, and is a testament to the existence of trends regarding beauty and adornment, or ‘cultus’, in the ancient world. It demonstrates the shared care, cultivation and pride in appearance between ancient and modern societies. Beauty, as a complex concept often expressed through clothes, hair, and makeup as well as posture, physique, and behaviour, dictated everyday decisions regarding personal presentation.

In imperial Rome, there were certain criteria which had to be filled in order to be perceived as a beautiful or desirable woman. To satisfy this set of tick boxes one would have to demonstrate high status and wealth. Hair colour and style were essential components in forming the upper-class Roman woman between the firstcentury BCE and the thirdcentury CE. Sculpture records hairstyles, particularly the use of wigs, and the volume of portraiture depicting women in formal dress with extravagant hairstyles, typically mimicking that of the current empress, reveals how fundamentally important art was in expressing beauty and Roman ideals. An ancient portrait would have been carefully carved to reflect the attitudes and values of the time in order to present the subject in the optimum light for centuries to come.

Beauty was full of unspoken rules and implied meanings. Portraits demonstrated social, political, intellectual and moral alignment; portraiture was not a method of self-expression or capturing a specific moment but was a device to demonstrate an enviable lifestyle, exhibiting the most elaborate hairstyle, ability to afford expensive materials, and slaves to achieve it. That is why I have chosen this statuary hair piece for this article as it epitomises the power and importance of portraiture in expressing identity and social status.

|

Figure 1. A detachable marble wig from a female bust, Severan period. Thermen Musei, Rome. Olson, (2008), 72; Photo: Singer/DAI neg. 1972.2979. |

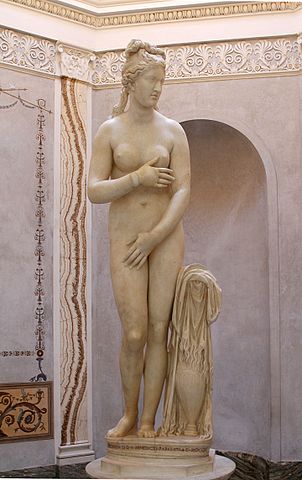

Visually pleasing facial festures were generally not contributing elements to a woman's beauty; beauty was attributed to wealth and status, portrayed through adornment, opulent hairstyles, shining jewellery and items such as wigs which acted as special additions, elevating the subject, increasing their ‘beauty’. The practice of wearing fake hair and purchasing wigs is referenced in ancient texts, with Ovid explaining that a woman's curls were 'bought' and she pays for hair from another (Ovid, Ars Amatoria, 3.3.33-4). One could understandably assume that, since modesty was often desired in a woman, Roman women would have kept their hairstyles neat and simple, not adorning themselves with extravagant wigs, but this is a modern lens, and the ancient process of wearing a wig actually covers the hair, and thus the hair is modestly kept out of sight. In reality, a wig may have been worn on occasion by a woman, but in the portrait, it acted as a symbol that went further than a fashion statement. Elegant hair controlled by pins, plaits and curls signified the civilised woman compared to natural, unrestrained and messy hair, associated with something slightly more barbaric, such as a foreigner or woman in mourning. The marble wigs are carefully carved to show every curl and element of detail. Having a wig would be something one would want to show off; there are even statues that depict the subject sporting a wig with their own hair visible from underneath so people could be assured it was not their real hair and they were wealthy and high-class enough to wear wigs (Figure 2.)

|

Figure 2. Profile view of a woman in a wig. Early third century CE (?). Capitoline Museum, Rome. Olson (2008) 74; Photo Faraglia/DAI neg. 1940.1059. |

|

It would not be insignificant that a woman was portrayed in a specific way as this may be the only portrait that survives of her and thus the way she is remembered in perpetuity. The fact that most private portraits are relatively easy to date, since they have 'period-faces', ie. faces comprised of a set of elements and styles widely used in a particular period, and distinguishing coiffures that mimicked those of the imperial family at the time, demonstrates a distinct lack of self-expression and individualized beauty, eliminating reason to believe that ancient beauty had a spectrum. Roman styles and the portraiture which reflected them suppressed uniqueness and championed the appearance of a collective: proportional, youthful faces were common, with hairstyles being the same from private woman to empress, simply demonstrating elevated status. This allowed the imperial family to be viewed as the ideal Roman family, as well as the upper-class women to be viewed as even higher status and akin to imperial women in morality and values. Hairstyles functioned as a uniform: wigs with ornate but controlled styles began to signify a group identity of higher status and thus someone worth social recognition. Soon all upper-class women resembled each other, no one wanting to be excluded from this elite club, and thus no one risking a different hairstyle.

One of the central aspects to a Roman woman’s image, and one that governed the beautification process, was the reciprocal close relationship between the empress and her private women. The relationship is proved by the intentional difficulty in distinguishing between images of the empress and of another private woman. As the imperial family, and thus the basis to model oneself on was everchanging, hairstyles were constantly evolving, as was beauty. The desperation to keep up to date with what was fashionable or acceptable at the time can be seen in the number of statues that have detachable hairpieces: there are about 25 statues of women surviving from the Antonine and Severan periods with this detachable element. This was thought to have been so the subject was able to keep up to date with the current trending hairstyle without getting a new bust every time. It was even thought that these could have been funerary busts with the subject wanting her image to stay current even posthumously, with a family member swapping out the hairpieces, thus demonstrating how important hairstyles were in reflecting status.

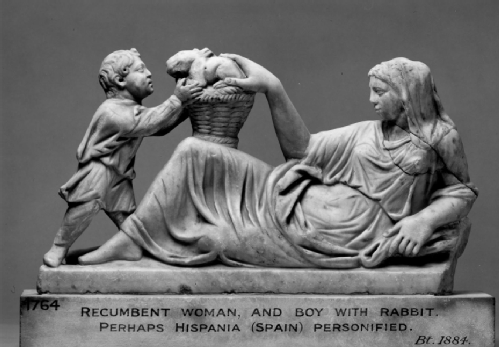

Julia Domna, empress from 193 to 211 CE and wife of Septimius Severus, had a notable hairstyle and was arguably the wig’s most prominent patron. She wore a heavy, globular wig with finger waves and a centre parting (Figure 3). We can see the similarities in the detachable wig piece (Figure 1) to the empress’ styles with the hair in a neat formation directed towards the back of the head. Julia Domna adopted a wig to imitate her predecessor, Faustina the Younger, thus demonstrating that familiarity and replication were sought after.

|

Figure 3. Bust of Julia Domna, though not certain identification as little distinguished private women. ca. 200 CE. Capitoline Museum, Rome. Stuart Jones (1912) Catalogue of the Capitoline Museum, 103, no. 27. |

Julia Domna was the daughter of a high-ranking priest from Syria and this style with the centre-parting and waves is indicative of those provincial origins. This detachable wig piece, epitomising Roman fashion, thus also demonstrates the infiltration of trends and styles from other geographic areas into Rome. There is even a theory that the detachable marble wigs existed to accommodate the Syrian ritual of anointing the skull of the bust with oil, again illustrating the possible fusion of cultures that occurred in Rome.

While beauty is not a modern concept, elements of modern-day beauty can be observed in ancient material. These statues, primarily the detachable wig piece, encapsulate the importance of keeping up with trends, as well as being inspired by role-models or prominent figures. Since Roman beauty did not necessarily mean looking aesthetically pleasing, the ancient word ‘cultus’ translated as ‘care of the self’, ‘fine appearance’ or ‘apparel’, may be a more appropriate term than beauty. It suggests the idea of cultivation or lavishing attention and thus better captures the attitudes and representations of women who focused on factors such as artificial adornment regarding appearance. Hair transcended surface level preferences and was a key element in expressing social and moral alignment; beauty was beyond superficial.

Bibliography:

Primary Sources:

Ovid, The Art of Love, trans. A. S. Kline, (Poetry in Translation 2001: https://www.poetryintranslatin.com/PITBR/Latin/Artoflovehome.php, last accessed 29/03/22)

Secondary Sources:

D’Ambra, E. (2007), Roman Women, (Cambridge University Press).

D’Ambra, E. (2014), ‘Beauty and the Roman Female Portrait’ in Art and Rhetoric in Roman Culture, ed. J. Elsner & M. Meyer, (Cambridge University Press), 155-80.

Davies, G. (2008). ‘Portrait Statues as Models for Gender Roles in Roman Society’ in Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, Vol. 7, (University of Michigan Press), 207-220.

Fejfer, J. (2008), Roman Portraits in Context, (Walter de Gruyter).

Fischler, S. (1994), ‘Social Stereotypes and Historical Analysis: The Case of the Imperial Women at Rome’ in Women in Ancient Societies: An Illusion of the Night, ed. L. Archer, S. Fischler, & M. Wyke, (Basingstoke and London), 115-133.

Kleiner, D. & Matheson, S. (1996), I, Claudia: Woman in Ancient Rome, (Yale University Art Gallery: Austin, Texas).

Meyers, R. (2015), ‘Female Portraiture and Female Patronage in the High Imperial Period’ in A Companion to Women in the Ancient World, ed. S. L. James & S. Dillon, (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd), 453-466.

Olson, K. (2008), Dress and the Roman Woman, (Routledge).

Scott, J. W. (1986), ‘Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis’ in The American Historical Review, 91. 5, (Oxford University Press, American Historical Association), 1053–1075.

Trimble, J. (2011), Women and Visual Replication in Roman Imperial Art and Culture, (California: Stanford University).

Wyke, M. (1994), ‘Woman in the Mirror: The Rhetoric of Adornment in the Roman World’, in Women in Ancient Societies: An Illusion of the Night, ed. L. Archer, S. Fischler, & M. Wyke, (Basingstoke and London), 134-151.

|

This article was written by Tallulah George, a postgraduate student at the university of Warwick, studying towards a taught MA in the visual and material culture of ancient Rome. Her interests are in identity, self-representation and portraiture, and ancient societal structures. Tallulah is passionate about making classics relevant to wider audiences and making it relatable to the modern day, check out her website to see how she does this!https://classicsbytallulah.co.uk |

Jacqui Butler

Jacqui Butler

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…