All 21 entries tagged Economics

View all 245 entries tagged Economics on Warwick Blogs | View entries tagged Economics at Technorati | There are no images tagged Economics on this blog

September 08, 2010

Why Bad Economics is Like Bad Art

Writing about web page http://whatpaulgregoryisthinkingabout.blogspot.com/2010/09/do-we-need-new-economics-101.html

It's economics bashing time again.

The latest to have a go is Gideon Rachman in yesterday's Financial Times. "Sweep economists off their throne!" he demands. He compares economists unfavourably to historians, "archive grubbers" who at least have a sense of modesty about their claims to rigour. He goes on to complain about the "brash certainties, peddled by those pseudo-scientists, otherwise known as economists."

As an economic historian -- and I do grub around in archives -- I suppose I have some sympathy for this view. Only a year ago I was writing about the advantages of history in helping us see what's coming round the next corner.

But as a trained economist I think it misses the point.

Good economics isn't brash and doesn't make unjustified claims of predictive power. Specifically, good economics is not the handmaiden of the journalists and politicians who most want economics to support their nostrums and interventions. My Hoover colleague Paul Gregory makes a powerful case that what our first year students have been learning is still pretty much on the button in today's world. It is, above all, an economics that promotes scepticism, critical thinking, and the avoidance of Type I errors.

My point is that there is not just "economics." There is good economics and bad economics. I don't care if it is radical, liberal, conservative, or what. It's interesting that good economics of every school or tradition has more in common with the good economics of other schools than it has with bad economics of any school.

The problem is that there is always a demand for bad economics and there is also a plentiful supply of it. Why? We won't discuss good and bad physics, because that annoys too many people. Instead, think about bad art. On the supply side, untalented artists exceed the number of talented ones by a large margin. So, bad art is abundant. The same is true of economists; there are many more people like me that are writing about economics, for example, than there are Keyneses, Hayeks, and Friedmans. (I hope there's an even larger number of economists that are worse than me, but that's not for me to say.)

On the demand side, many people (myself included) are not really sure of the difference between good and bad art. Also, there are many reasons why we positively desire bad art: because it is comfortable; because it fits with the decor of the room we live in; because it promotes our fantasies without transcending them; and, particularly, because some critic tells us it is good when it's not. I'm sure I personally subscribe to at least some bad art for each and all those reasons.

The demand for bad economics is similar. In fact, just as critics and reviewers mediate the demand for bad art to the public, bad economics has a bunch of people that do the same job of telling the public to buy it. Who are they? Well, many of them are politicians and, er, journalists.

Since this is about economics, we should also think about price. Good economics is relatively scarce, difficult, and uncomfortable; it's designed for truth, not reassurance. In short, the price is high. Bad economics is abundant, soft, and easily absorbed. For all these reasons, it's cheap.

In fact, I'm fairly sure some of the journalists that are now hopping mad at economists are mad just because they themselves previously invested too much of their beliefs in bad, cheap economics. I once had a rather ill-mannered go at Anatole Kaletsky of The Times on this score. Not all of them are to blame, though, and specifically not Gideon Rachman. (I checked out what Rachman was blogging about before the crisis broke in 2007. At least, he wasn't promoting buy-to-let.)

Anyway, let's get back to sweeping the bad economists off their throne. Get rid of them; then what? Who are we going to ask about the economy? Sociologists? Some guy in the pub? Use common sense?

The trouble is, this is a surefire way of replacing bad economics with ... more bad economics. It was Keynes, himself a great economist, who wrote:

Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.

July 26, 2010

The Return of Animal Spirits?

A student asked me recently if the economists' consensus is that deficit reduction should be delayed until private demand has picked up -- which might not be any time soon. My first response was to point out that, while this might easily be the impression gained by reading the pages of The Guardian, a number of distinguished economists take the view that global demand would benefit from a more rapid fiscal adjustment. My Hoover colleague John Taylor has listed some of them here.

I also considered how to explain the wide range of disagreement to my student. Model uncertainty is part of the story, reflected in divergent views about the value of the government spending multiplier. According to President Obama's advisers, a government consumption stimulus of 1% of GDP will add 1.55% to U.S. GDP over 16 quarters, i.e. every $1 of federal spending should create another 55 cents of private consumption and investment. A recent IMF paper, in contrast, estimates that the effect goes nearly to zero over the same period, i.e. the same $1 of federal spending eventually reduces private consumption and investment by an equal amount.

Just as importantly, I wondered whether, in addition to differences between models, there is also inconsistency within models -- specifically, within the Keynesian model as some are applying it currently.

Think of Keynesian economics as incorporating two key insights. One is the problem of effective demand, and the spending multiplier that augments the effect of any income shock on aggregate demand. The other is the problem of unpriced uncertainty and the human reaction to this problem, which Keynes called "animal spirits." It seems to me that Keynesians are sometimes unjustifiably selective in applying these two insights.

To simplify, the Keynesian narrative of the crisis should have both main elements. On the way down they work like this. Borrowers and lenders failed to price the uncertainty in asset markets. Animal spirits soared, then collapsed as reality struck home. When animal spirits collapsed, they took down effective demand and there was a sharp multiplier contraction. It's a coherent and interesting diagnosis. Now we have the problem of getting back up. What should the Keynesian narrative of the recovery look like? Here the prescription of leading Keynesians (I'm thinking of Paul Krugman, Brad deLong, and my Warwick colleague Robert Skidelsky) becomes curiously one sided; there's the multiplier -- and just the multiplier. Animal spirits aren't in the picture, so private demand is destined to be flat. In this view, the only thing that can get us back up off the floor is discretionary government spending. That's why, they argue, deficit reduction right now is crazy.

On top of that are the politicians and the journalists. There is a lot of Keynesian-inspired "never again" publicism around at the present time. This might be stretching it a bit, but the spirit of it is pretty much: Animal spirits got us into this mess -- never again! Animal spirits are bad -- let's kill them off, once and for all! We need rules that will put a stop to irrational behaviour! Let's appoint sensible people to take charge and just not let that happen any more!

This is absolutely not the spirit of Keynes. Keynes did not say that animal spirits are a bad thing or that we should get rid of them. He said that animal spirits are a source of instability, and they are hard to manipulate; but they are also the driver of capitalist enteprise and we cannot get away from them or do without them. Here I'm going to quote a few sentences from Keynes's General Theory of 1935 (which is on line here). First, Keynes suggests that enterprise relies on animal spirits as much as business calculation:

Even apart from the instability due to speculation, there is the instability due to the characteristic of human nature that a large proportion of our positive activities depend on spontaneous optimism rather than on a mathematical expectation, whether moral or hedonistic or economic. Most, probably, of our decisions to do something positive, the full consequences of which will be drawn out over many days to come, can only be taken as a result of animal spirits — of a spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction, and not as the outcome of a weighted average of quantitative benefits multiplied by quantitative probabilities. Enterprise only pretends to itself to be mainly actuated by the statements in its own prospectus, however candid and sincere. Only a little more than an expedition to the South Pole, is it based on an exact calculation of benefits to come.

When animal spirits falter, so does enterprise:

Thus if the animal spirits are dimmed and the spontaneous optimism falters, leaving us to depend on nothing but a mathematical expectation, enterprise will fade and die; — though fears of loss may have a basis no more reasonable than hopes of profit had before.

Without animal spirits there is no progress:

It is safe to say that enterprise which depends on hopes stretching into the future benefits the community as a whole. But individual initiative will only be adequate when reasonable calculation is supplemented and supported by animal spirits, so that the thought of ultimate loss which often overtakes pioneers, as experience undoubtedly tells us and them, is put aside as a healthy man puts aside the expectation of death.

Policy makers must legitimately reckon with the effects of politics and policy on animal spirits:

This means, unfortunately, not only that slumps and depressions are exaggerated in degree, but that economic prosperity is excessively dependent on a political and social atmosphere which is congenial to the average business man. If the fear of a Labour Government or a New Deal depresses enterprise, this need not be the result either of a reasonable calculation or of a plot with political intent; — it is the mere consequence of upsetting the delicate balance of spontaneous optimism. In estimating the prospects of investment, we must have regard, therefore, to the nerves and hysteria and even the digestions and reactions to the weather of those upon whose spontaneous activity it largely depends.

It's Keynes's last point that so-called Keynesians should pay more attention to. Reckoning with animal spirits does not mean that we are now somehow ruled by "the markets," as Robert Skidelsky suggested recently. It does mean giving thought to how policy can encourage animal spirits to revive -- and how policy mistakes can do further damage.

At the core of today's policy dilemma is this question: How does the government's budgetary policy influence animal spirits? It's a difficult question because it cuts both ways. Deficit spending by the government is good for animal spirits, other things being equal, because it floods the economy with demand and floats us all upwards. But other things are not equal. The deficit adds to the debt. Public debt must be financed, and a growing debt implies a rising tax burden that, looking to the future, must depress animal spirits.

So, there are two effects: deficits are a positive, but debt is a negative, and you cannot have the deficit without adding to the debt. Of the two effects, which today is the greater? It's hard to be sure, because animal spirits are as incalculable as the uncertainty to which they respond. In fact, we don't really know. On top of that, when policy outcomes are uncertain, and we fail to make a clear choice, we have policy uncertainty. As Robert Higgs has shown looking at the Great Depression, policy uncertainty is more bad news for animal spirits.

In short, there exists a Keynesian argument for decisive fiscal retrenchment now -- and it is more coherent and truer to Keynes than the positions adopted by some latter-day Keynesians. Deficit reduction is likely to take away from demand now via the spending multiplier (which may however be small, or become small or even go to zero over a few years). At the same time deficit should add to demand to the extent that it slows the accumulation of debt and encourages business confidence in the future, and also because a clear choice in favour of enterprise also builds confidence.

Contemplating deficit reduction, can we be sure of the results? No. Past behaviour gives us only rough averages as a guide; for example, Reinhart and Rogoff suggest that the median long term growth penalty for pushing debt above 90% of GDP is 1% a year. There's a lot of variation around that figure, which reduces the predictability of the outcome. So, is there an element of gamble in debt reduction now? Absolutely. But is there a safe or low-risk alternative? No.

The jobs and welfare of hundreds of millions of people are at stake in the fiscal policy game being played out now in the capitals of the West. But it's not a game we can refuse to play.

June 03, 2010

Israel and Gaza: When Sanctions Fail

Writing about web page http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/10195838.stm

Israel's deadly assault on the SS Mavi Marmara, the Turkish aid ship bound for Gaza, has evoked worldwide protests and condemnation. Not only that, it promises to undo Israel's three-year blockade of Gaza. Egyptian President Mubarak has ordered the reopening of Egypt's closed border crossing to Gaza. U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has called the situation in Gaza "unsustainable." Israeli relations with Turkey are clearly at risk; responding to popular protests, Turkish Prime Minister Erdogan has called Israel's raid a "bloody massacre."

In many ways Israel's use of sanctions to isolate and weaken the Hamas rulers of Gaza has followed a predictable course, up to and including its calamitous denouement. In the last hundred years trade sanctions and blockades have been employed in many conflicts, from World War I to Iran and North Korea today. It's possible to draw three lessons from this experience:

- Trade sanctions are generally slow to take effect on the country that is sanctioned and have fewer economic effects than expected. This is because, when a country is denied access to commodities that were previously imported, new ways of living without them turn out to be available. Economies are made or substitutes found. There are few limits on the ingenuity that can be brought to bear, provided the will is there. Even poor communities find workarounds. Of course, trade sanctions do make everyday life more difficult and raise the costs of resistance.

- Trade sanctions are usually very costly to impose. The country that imposes them has to meet the economic and political costs of enforcement. The economic costs alone can be large or small depending on the particular situation, but these are at least fairly predictable. The political costs are rarely foreseen beforehand, but can turn out to be even more important. For example, trade sanctions generally have strong political effects that are negative from the point of view of the blockading country. Within the blockade, the effect is to stiffen national feeling, which consolidates support around the government. As a result, the will to maintain resistance turns out to be there, whether or not it was there previously.

- Trade sanctions can also have strong political effects on the international community, and these too can be counter-productive. This is because trade sanctions cause collateral damage, some of which hurts the commercial interests and citizens of neutral countries. In turn, this affects neutral opinion. In some circumstances, the result can be to convert neutral countries into allies of the country that is sanctioned. This is not inevitable, however.

Trade sanctions are often imposed in the expectation that they will quickly cause the adversary's economy to break down or, failing that, to cause the adversary government to reach an acceptable compromise. Alternatively, they are advocated by well meaning humanitarians who prefer non-violent ways of changing the adversary's behaviour. But it is hard to think of a case where trade sanctions actually worked in that way.

Historically, trade sanctions generally did worsen the economic conditions of the sanctioned population and signficantly increased the economic costs of maintaining resistance, as intended, although by less than expected. The political effects, in contrast, tended to work in the other direction, making it easier for the sanctioned government to impose the economic costs on its community. Any payoff to the sanctioning power did not materialize in less than several years and often, even then, only when combined with direct military action.

A clear illustration can be found in World War I. From an early stage in the war, Germany imposed a submarine blockade on the British Isles. Since Britain imported more than three quarters of the food calories consumed in peacetime, German naval strategists believed this was a war winning weapon. Eventually, however, the blockade may have done more damage to Germany than to Britain.

How did Britain survive the blockade? Countermeasures included wartime expansion of home agriculture, its restructuring away from meat to cereals, and rigid prioritizing of convoy shipping space. These measures, although costly, were so effective that, despite a large reduction in food imports, there was no deterioration in wartime nutritional standards for the British population. This illustrates well how the principle of substitution can lessen the effectiveness of blockade in comparison to what is expected beforehand.

The blockade was extremely costly for Germany, which had to build and operate hundreds of ocean-going submarines and replace heavy losses at sea in order to sustain a blockade that was only partially effective. The political costs to Germany were even more disastrous. Within Britain, the political effect was to stiffen patriotism and national resistance.

Internationally, Germany's efforts to tighten the blockade led to the sinking of neutral ships, with their cargoes, crews, and passengers, and to the deaths of neutral citizens carried by British ships. As a result, the neutral community became more sympathetic to Britain. In the first years of the war, the most important neutral power was the United States. It was the German policy of unrestricted submarine warfare that progressively antagonized American opinion and brought America into the war in 1917. America's entry into the war ensured Germany's defeat. These effects illustrate how the political costs of trade sanctions can outweigh any benefit to the blockading power.

During World War I, Britain also blockaded German trade. This was achieved bloodlessly, by a combination of the control of surface shipping and diplomatic pressure on Germany's neutral neighbours. Of course this was very costly to Britain but one difference is that Britain did not lose as many friends as Germany. The main reason is that Britain did not need to attack neutral assets or victimize neutral citizens to enforce its blockade of Germany. In contrast, Germany could not attack British trade without sinking neutral ships and shedding neutral blood.

This is now Israel's problem with Gaza. Until recently, both Israel and Egypt had a common policy of opposing the Hamas administration in Gaza by means of trade sanctions. The sanctions have had some positive effects. Syria and Iran have not been able to resupply the Hamas militants with armaments to attack Israel, which no longer faces daily bombardment. But sanctions have not succeeded in bringing Hamas down or changing its goals. They have not freed the Israeli soldier Shalit Gilad. The economy of Gaza has been reduced to a low level but is maintained there by sanction-busting gangs of criminal entrepreneurs whose profits depend on the blockade, on smuggling through it, and on the distribution of smuggled goods.

The aid flotilla, and Israel's heavy handed response, have broken this equilibrium. The siege has been ended, temporarily at least, on the Egyptian border. Having lost the cooperation of Egypt and Turkey, Israel cannot reimpose sanctions without undertaking measures that are likely to further alienate world opinion; possibly, Israel cannot reimpose it at all. In this way the blockade of Gaza has conformed with historical experience.

I say this without considering the morality of the opposing sides and their actions. Israel has the right to defend its citizens against their enemies. But the blockade of Gaza has ceased to be a means to that end.

May 17, 2010

Fear of Floating

Writing about web page http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/77b0362c-5cf1-11df-bd7e-00144feab49a,dwp_uuid=79cadde4-5c1b-11df-95f9-00144feab49a.html

It was intriguing to read in the FT (May 11) about Eurozone resentment at Britain's lack of participation in the Greek bailout. In fact, it goes beyond that:

Charles Grant, director of the Centre for European Reform, said there was increasing anti-British feeling across the EU, fuelled by the belief that Britain had allowed its currency to depreciate to gain a competitive advantage.

I wondered what to think about this. It's true that sterling has depreciated quite substantially since the beginning of the crisis. Without that, the UK economy would be in much worse shape today, with still higher unemployment and a bigger budget deficit. So, it is true that the eurozone has been feeling some of our pain.

On the other hand, the reason Britain didn't join the euro in the first place, rightly or wrongly, was to retain the some insulating flexibility in the sterling-euro exchange rate if things went wrong. It wasn't compulsory for us to join the Euro, any more than Greece or Portugal were forced into it. They chose to and we didn't. Now this choice has proved correct, it's hard to understand why we shouldn't be permitted to benefit from it.

Some Europeans believe, apparently, that to benefit from a currency depreciation is morally wrong. In that case, what about the euro itself? The euro has a flexible exchange rate vis à vis the rest of the world. If the euro depreciates against the dollar or the yuan, then the entire eurozone will gain a competitive advantage over American and Chinese producers. In fact, in the last month the euro has depreciated by about 10 per cent against the dollar.

If it's right to avoid competitive depreciation, I expect to see the ECB intervening in the markets to sell euro denominated bonds and drive the value of the euro back up again. But actually ... Oh! I think they're doing the opposite-- on an unprecedented scale.

That's probably a good thing, at least in the short term, for Europe as a whole, even if it will do little for the long term solvency and prospects of the countries that are hurting most -- Greece, in particular.

As Barry Eichengreen and Doug Irwin have shown, in the Great Depression the countries that came off the Gold Standard earlier recovered quicker; those that prioritized exchange rate stability found little alternative to the policies of protectionism and regional autarky that eventually destroyed the global economy.

April 30, 2010

Poor Greece — Poor Us?

Greece at the mercy of "the markets." Hundreds of thousands faced with job cuts, lower salaries, and longer to work until retirement. It's hard not to feel sorry.

Equally, it's easy to understand the wrath of many Greeks: why should foreign bond holders have such power over the domestic policies of a sovereign state? Why should they accept the diktats of the IMF?

There is a simple answer. For many years, the Greek government spent far more than it raised in taxes. Why? It was the easiest way to buy votes. The problem was that the Greek government could not do it without the cooperation of others: those willing and able to lend it it.

Some of these were Greek financial institutions such as pension funds. But 80% of the Greek debt is held abroad, much of it with German and French banks. But these have walked away, taking the ball with them.

Now that the markets have called an end to the game, those who want to stand up for the entitlements of the Greek workers have to ask where the money will come from. Here are the options:

- Continue to borrow on the market -- but who will lend? The Greek debt is already at or beyond the margin of sustainability (on which more below). It is not an attractive prospect.

- If not borrow, then take. One option for the Greek government is to take from the lenders that previously enabled the years of pleasure and are now causing the pain. Taking without permision is normally called taxation. In this case it is called default. For Greece, default is all the easier because most of the lenders are abroad; they do not vote and are unlikely to throw rocks. Unilateral default has one problem: you can only do it once. After that, there is the same problem as before: if the voters want the Greek government to spend more than it raises in taxes, they must borrow. But who will lend?

- If neither borrow nor default, then print money. For most sovereign states, printing money would fix several things at once. The new money would cover the budget deficit. Then there would be inflation, but inflation would erode the real value of the debt. After that there would be a disaster, but hey ... But Greece cannot go down this road, even if it wants to. When it joined the euro, Greece gave away the right to print its own money.

- If neither borrow, nor default, nor print money, then ... raise taxes and cut spending, because there is nothing else that can be done.

These are Greece's options. In fact, the conditions that the EU and the IMF are "imposing" on Greece -- to raise taxes and cut spending -- are just what Greece must to do anyway, because there are no other choices that don't end in disaster.

Even that might not be enough. Government revenues are currently around one third Greece's GDP. If the debt heads for 140% of GDP and then stops, and must be refinanced at 10%, it follows that in future taxation must transfer 14% of GDP annually to bondholders in interest payments, and these alone will use up around 40% of Greece's limited tax capacity. Moreover, around 80% of Greek debt is held abroad, so those interest payments must shift more than a tenth of Greek GDP abroad each year -- just to cover the service on the debt, not to reduce it. The currrent EU-IMF bailout assumes that Greece's problem is liquidity. But what if it is solvency?

In that case, the future still holds the possibility of default. Given more time there will perhaps be an organized, agreed default. A rescheduling of repayments agreed with Greece's creditors will not kill Greece's credit ratings for ever, provided Greece adheres to the conditions imposed upon it.

One way of thinking about the Greek government yesterday, if not today, is that it stood at the centre of a web of obligations: legal obligations to bondholders, moral obligations to public sector employees and pensioners, and political obligations to voters. What the world has found, adding these up, is that they total far more than Greece's available resources. Something must give.

Greece holds one card, and it is an important one. If Greece goes down, so do its foreign bondholders. The German government has faced the choice between bailing out Greece and bailing out its own banks. It is interesting, and not inevitable, that the German administration has chosen in favour of Greece rather than to let Greece go and pick up its own pieces afterwards. This illustrates two things: the importance of politics, and the well known saying widely attributed to Keynes: "If I owe you a pound, I have a problem, but if I owe you a million, the problem is yours."

In all modesty, how far from Greece are we? Expectations of the British government, and what it can do for lenders, employees, the young, the old, the sick, and voters at large, have also become overstretched. Like Greece, the UK has a government that overspends, with a budget deficit of similar size relative to GDP. As in Greece, public spending is much more important to the UK economy than it should be. Even before the crisis, its importance was rising steadily; public spending accounted for nearly half of the entire increase in GDP over the period of the Blair-Brown government from 1997 to 2007. Since the start of the crisis, the growth of public spending has accelerated. Right now, public spending amounts to more than half of the UK's GDP.

In some other important ways, we are much better placed than Greece. Our aggregate debt is smaller relative to GDP, with less need for near-term refinancing. More significantly, the UK has a much greater fiscal capacity than Greece, with better coverage of tax raising institutions and less avoidance. We will be able to raise the taxes we need to finance the debt we have. And we will raise them, for another important reason: more of our debt is held at home, so lenders are also voters.

Finally, and crucially, we are not part of the eurozone. That matters, not because it will let us print money, but because it will let us recover from fiscal adjustment. The coming squeeze on spending and tax increases will put a cramp on jobs and demand from the public sector, but further depreciation against the euro and dollar will eventually rebalance the economy, allowing exports and private spending to take its place.

If there is a parallel with Greece it is not in the national picture but the regional one. For the UK as a whole, the ratio of government spending to GDP is currently a little over one half. For Ireland, Wales, and the Northeast it is between 60 and 70 percent. These regions are not only hugely dependent on public subsidies but they have no chance of renewed competitiveness through currency depreciation because, like Greece, they belong to a currency union -- in their case, the United Kingdom. What keeps them going is an unconditional year-on-year bailout from central government revenues.

My vote is not yet decided, but these are some of the reasons why I am taking seriously what the conservatives have to say about the economy today. Darling called the first phase of the crisis far more astutely than Osborne, and labour deserves credit for that. I am not convinced that more of the same will take us into a recovery.

April 16, 2010

Privatized Keynesianism: Rebirth After a Life That Never Was?

Writing about web page http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/122498671/abstract?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0

"Privatised Keynesianism: An Unacknowledged Policy Regime," published in the British Journal of Politics & International Relations11:3 (2009), pp. 382-399 by my Warwick colleague Colin Crouch, has been deservedly recognized and cited by scholars and journalists. The paper starts from the idea that it is a problem to maintain stability and consumer confidence under capitalism. These were secured for thirty years after the war by Keynesian demand management. After that, Crouch writes:

In those countries where capitalism was moving into full partnership with electoral democracy, it was acquiring a new vulnerability. In a fully free market, wages and employment were likely to fluctuate; would workers, who were dependent on their incomes for their level of living and lacked the cushion of wealth of propertied classes, be confident enough to consume at levels adequate to enable capitalists themselves to sustain confidence to invest and maintain profit levels? Would the very characteristics of the market that constituted its strength—flexibility, especially of labour—undermine its own ability to thrive? It should be noted that we are not here talking of the market producing social problems of insecurity in workers’ lives—that might be dealt with by an adequate welfare state—but of its producing problems for itself through its own dependence on workers’ willingness to maintain and increase their consumption. It can be assumed that the level of living at which social policy will sustain purchasing power will be below that needed to sustain an expanding, consumption-driven economy.

And he continues:

In the 1940s it had seemed that only state action could solve this problem for the market. But now, absolutely in tune with neo-liberal ideology and expectations, there was a market solution. And, through the links of these new risk markets to ordinary consumers via extended mortgages and credit card debt, the dependence of the capitalist system on rising wages, a welfare state and government demand management that had seemed essential for mass consumer confidence, had been abolished. The bases of prosperity shifted from the social democratic formula of working classes supported by government intervention to the neo-liberal conservative one of banks, stock exchanges and financial markets.

I have thought about this a lot recently, partly because my students love it -- and reproduce it for me in their essays! I have to say I don't buy it -- at least not in this form. Why am I sceptical? Well, Crouch's argument seems to be that capitalism is vulnerable to underconsumption. From 1945 through the 1970s, the argument goes, the British government ensured demand was sufficient. After the 1970s, Crouch suggests, government retreated and banks stepped in. In his eyes, British capitalism survived on credit.

The big thing here that is clearly true is that as the public debt declined, household debt rose. My problem is with the counterfactual. Implicitly, without government spending in the first phase, and credit expansion in the second, there would have been a problem: not enough demand. In the first phase, that is for most of the period up to the 1970s, it's clear that British capitalism actually suffered from too much demand; that's why there was rising inflation. In the second phase, after the 1970s, the government didn't so much step out of the picture as try to limit demand more fiercely (and hamfistedly at first), eventually delegating the job to the Bank of England. In this phase I don't really see any evidence that British capitalism was going to fall into decline if we hadn't been able to lend lots of money to the workers that they couldn't afford to pay back.

With less household borrowing and less equity realization, what would have happened? Most likely, interest rates and the exchange rate would have been a little lower, and exports would have been a little higher. With more export competitiveness, our manufacturing sector would have declined a little more slowly (and our universities might have expanded a little more). That's about it. Oh, and I guess we would be in slightly better shape today.

Ironically it is only now, in the current recession, after a huge credit crunch and collapse of private demand, that privatized Keynesianism has truly come to life. Hence, in my view, its rebirth, after a life that never was. Here is some evidence, which you'll note is tri-partisan:

-

BBC, July 23, 2009: Chancellor Alistair Darling has urged banks to lend more to small firms, during a meeting with banking bosses ... Alistair Darling has said he is "extremely concerned" that banks may be charging firms too much for loans.

-

Reuters, October 26, 2009: British retail banks should stop paying big cash bonuses and use the money instead to support new lending and contribute to an economic recovery, opposition Conservatives’ finance spokesman George Osborne said on Monday.

- The Guardian, February 23, 2010: A new government should tear up "ineffectual" lending agreements with Britain's taxpayer-owned banks and force them to lend billions of pounds more to small and medium sized businesses, Liberal Democrat Treasury spokesman Vince Cable said today.

Thanks to Colin Crouch, we know what to call it: Privatized Keynesianism. It is Keynesian because it uses debt finance to add to aggregate demand. It is privatized because the debt is private and stays off the government's books.

Now, the question is: Is privatized Keynesianism a good idea for today? Hmm. Why are we in the mess we are in? I think it might have been that we had too much private debt in the first place, so banks lent too much to firms and households that had no chance of repaying their debts unless house and stock markets floated ever upwards; and because banks did not keep enough in reserves. Where are we now? House and stock prices are still too high, and they are rising. And the solution these politicos favour is ... more private debt! The bankers are letting us down! They should be out there trying to persuade us to take out more loans! They should be keeping less in reserves!

You couldn't make it up, could you?

At this point I am going to offer one of those dire aphorisms that runs: "The only thing worse than X is -X." I apologize in advance, but there is no alternative, so here it is:

- The only thing worse than having bankers making lending decisions is to have politicians making lending decisions.

This does not mean I am complacent about the need for better financial regulation. Politicians have a role to play, and it is in setting prudential rules, limiting guarantees to retail depositors, and removing the incentives for banks to grow "too big to fail." That is a lot, but that is all. Politicians should not be making lending decisions! That is the bankers' job; let them do it.

April 01, 2010

On the Floor: What is Stopping Our Economy Falling into the Basement?

Writing about web page http://johnbtaylorsblog.blogspot.com/2010/02/one-year-later-and-more-evidence-that.html

A couple of months back, John Taylor made the point that the U.S. recovery is being led by the private sector. The vaunted $787 billion fiscal stimulus package passed by Congress has played no role. This is for a simple reason: it hasn't happened yet. This led Taylor, rightly, to wonder what will happen when it does come on stream, most likely in the middle of the recovery.

Now that the 2009 Q4 figures are available, it is interesting to ask the same question of the UK economy. Recovery has started, or at least the decline has stopped. Where is the improvement coming from? Is it coming from private demand or public spending? Is it coming from home or abroad?

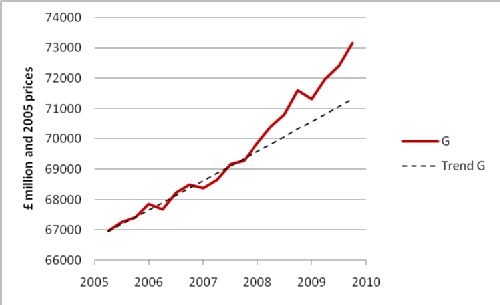

The chart shows the changes in the main components of GDP, in real terms, since 2008 Q1:

Source: ONS. G is general government consumption, NX is net exports, DInvent is the change in inventories, C is household consumption, and GFCF is gross fixed capital formation. Omitted are final consumption not by households, and net acquisitions of valuables.

The main picture is clear. Domestic private demand has collapsed. Until recently our economy was being held up partly by government consumption -- and even more so by foreign demand. (You might be surprised by that, given recent doom and gloom about the UK balance of trade. And there is a downside, which we'll come to.) The fact is that, from mid-2008 to mid-2009, the biggest support for the UK economy came from net exports.

Right now, however, government consumption is what is holding the economy up. I think the John Taylor question for the UK would be: Is the action on public spending currently any more than was already in the pipeline before the crunch? In other words, is active intervention or passive drift at work? This question is answered by the next chart, which strongly suggests active intervention:

Source: ONS. G is general government consumption. The trend is log-linear, calculated over 2005 Q1 (i.e. the last quarter of the previous Parliament) to 2007 Q4 (i.e. the last quarter before the GDP decline set in).

The chart shows clearly that, from the onset of the crisis, public spending began to move sharply upward from the trend established over the previous quarters going back to the last general election.

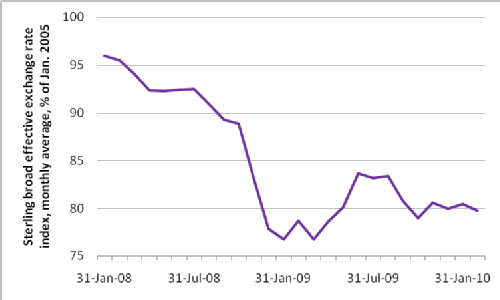

Another question is: How can we account for the net stimulus from trade, at a time when global demand was collapsing as fast as or faster than demand at home? There are two candidates: the foreign fiscal stimulus, and the domestic monetary stimulus. The deciding factor here is the real exchange rate. If global demand did the trick, boosted by the foreign fiscal stimulus that the G20 coordinated from the G20 last year, then the improved real trade balance should have been accompanied by an unchanged or rising real exchange rate. If it was quantitative easing pursued by the Bank of England, then we should see a declining real exchange rate. In the latter case, we saved ourselves by grabbing more than our share of global demand through competitive devaluation.

The next chart shows it was the Bank of England and competitive devaluation that did it.

Source: Bank of England. The series plots the broad sterling effective exchange rate monthly average.

The 30% decline in the real exchange rate through 2008 implies UK monetary policy was doing the larger share of the work. We grabbed a lifebelt, while others were beginning to drown -- Greece, lashed fast to the Euro, among them.

At the end of 2008, however, the depreciation of sterling came to an end. As a result, we are now even more dependent than we were a year ago on public consumption to hold up the economy. As the first chart shows, since the recovery began, the contribution of the trade balance has ceased to be positive. While household consumption and inventories are now showing small positive contributions, fixed investment is falling again. It's not a good picture.

What does this mean, given the public spending cuts now in prospect, whoever wins our coming elections? In principle, the real effect of public spending cuts on aggregate demand should not be entirely negative; lower government consumption should bring down interest rates and this should stimulate Britain's export sector through further currency depreciation. The trouble is that interest rates are already close to zero, and cannot fall further. Like the real economy itself, interest rates are on the floor but, unlike the real economy, cannot fall into the basement. For this reason it's hard to see how public spending cuts will translate quickly into improved prospects for recovery.

I understand that Britain has already too much public debt, of course, and will have to add to it in order to maintain public spending. We cannot do this without the cooperation of the lenders! This is why it is essential to plan for deficit reduction over the medium term.

At the same time, it is clear that the spending cuts in prospect are likely to cause double pain: not only a reduction in the level of public services, but also damage to the recovery of the real economy. Whatever government is in power, these are reasons to be very, very careful.

December 15, 2009

The Climate Hold–Up at Copenhagen: $60 trillion is up for grabs

Writing about web page http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/8413156.stm

The world's eyes are on Copenhagen, but there we have a problem. The world faces a deadly risk: the risk that we will boil the planet. There is a small chance the threat will go away, but I'm going to take it as read that, faced with a risk that is potentially catastrophic it is prudent to buy some insurance.

This risk, moreover, is a threat to us all -- rich and poor, young and old, black and white and in between. From a common sense perspective, that should make it easy for us all to agree on concerted action. Shouldn't it?

In a number of Hollywood films that I have seen (and enjoyed), a global calamity looms. The American president takes to the airwaves. He tells the world: "Let us set aside our differences and work together." The world listens. Will Smith saves us. The world applauds. The trouble is: This time, it isn't working.

The movie formula works because, in Hollywood, what is required to save the world is heroic action based on personal commitment, skill, and courage. The resources that support the hero are of interest but they are moral and technological; they do not absorb a significant fraction of even one nation's resources. International bargaining is not required.

Climate change, in contrast, puts the world's resources at risk, and cannot be solved without bringing the world's resources into play. Any solution requires multinational commitment, coordination, and bargaining.

Instead of a bargain, at Copenhagen we seem to observe only an agreement to differ. On November 2, 2009, Rajendra Pachauri, head of IPCC, told The Guardian:

I gave all the world's leaders a very grim view of what the science tells us and that is what should be motivating us all, but I'm afraid I don't see too much evidence of that at the current stage. Science has been moved aside and the space has been filled up with political myopia with every country now trying to protect its own narrow short-term interests. They are afraid to have negotiations go any further because they would have to compromise on those interests.

And yesterday I heard a BBC Radio 4 journalist describe the situation brought about by 190 nations each approaching the Copenhagen bargain with their own "red line" requirements as one of "negative negotiating space."

What's happening? How can that be right? In fact, how can it be rational? When human survival is at stake, what are the national interests that can prevent agreement? Isn't our common interest in conserving our shared planetary home the most fundamental interest that we have?

There exists a traditional explanation as to why climate change is hard to manage. In many ways it is a perfectly good explanation. Some call it the "prisoner's dilemma," while others call it the "tragedy of the commons," but the underlying idea is the same. Cutting carbon emissions requires self-restraint. The benefit of my self-restraint is spread over the entire world, so one six billionth of it comes back to me. The cost falls entirely on me, and so exceeds the benefit in a ratio of billions to one. That is why it suits each person's (or country's) private interest to let other people (or countries) go first in exercising self-restraint.

If others restrain themselves, I won't need to. If they don't, there's no point in it for me. This simple calculus explains why, even in the presence of scientific certainty, the climate problem will not solve itself.

By coming together at Copenhagen, however, the world's nations have an opportunity to take collective charge of this problem, internalize the spillovers, regulate access to the global commons that is our atmosphere, and coordinate on a first-best solution. An agreement is called for, and should be within reach. Why is it so difficult? We need other models to show why.

There is a certain similarity, as I see it, between the Copenhagen problem and what is sometimes called the "hold-up" problem. In the hold-up problem, two parties have relationship based on a shared asset in which both have a stake. The important thing is that this asset is worth more within the relationship than to the outside world. Inside the relationship the asset creates a surplus that is shared between both parties; without the relationship, the surplus would not exist.

There are many analogues for the hold-up problem, including a business partnership and a marriage partnership. In a marriage the "relationship-specific asset" can be knowledge of each other, shared activities, and even children. In a business partnership it can be a technology or way of doing things that is specific to the partnership and cannot be copied to some other use outside the existing business.

Within the partnership, the relationship-specific asset creates a surplus. How will the surplus be divided? In a relationship that works, there are agreed conventions or even (in a lasting marriage, for example) no strict accounting, just a rough sense of give and take. But there is also scope for exploitation. Each party will abandon the relationship if their share of the surplus is driven below zero; at this point, by definition, they would be better off outside. But this also means that one party can aim to appropriate more of the surplus by threatening a break-up, expecting the other to concede rather than lose everything. Each can hold up the other; that is why it is called the "hold-up" problem. This is what happens when children become hostages in a bad marriage, for example.

At Copenhagen, the relationshipship-specific asset is our atmosphere. What is up for grabs in the bargaining is, potentially, the entirely planetary surplus: the excess of global GDP over its unpriced cost: global carbon emissions times the social cost of carbon. How much is that? In 2008, global GDP was around $60 trillion. Global emissions were around 30 billion tons of CO2, or 8 billions tons of carbon. The social cost of carbon is usually put somewhere around $40 a ton, so the total damage is $320 billion, or around half a percent of global GDP. All the rest, more than 99% of global GDP, is the planetary surplus that we produce by exploiting our relationship-specific asset -- our shared planet. This surplus is what we stand to lose if we boil the planet. It is this surplus, $60 trillion less half a percent, that is up for grabs.

This tells us two things. First, the damage that we do to our home by living in it is currently trivial and should therefore be easily fixable. But the scope for redistribution is almost limitless. Effective bargaining can reallocate our entire planetary GDP.

There is one thing in the hold-up problem that we don't have. That is, we don't have an outside option. In the hold-up problem, the power of the exploiter arises from the threat to leave. No country can leave our planet. Where then does bargaining power come from?

Here we go back to game theory -- not to the prisoner's dilemma but to the game of chicken. In the movie Rebel Without A Cause (1955), two teenagers drive at each other on a narrow road. If one swerves, the one to swerve is a "chicken" and loses face. If neither swerves, both lose their lives. As in the game of climate change there is no outside option that does not involve extinction, but the game is played in the hope that the adversary will back down.

A well known result is that, if the game of chicken has a winner, it is the player that shows the most credible commitment. At Copenhagen the rich, poor, and middle income countries are on course for a three-way pile-up, but it is the richest and poorest that are competing to show the greatest commitment.

The commitment of the richest is made credible by two factors: first, unlike the poor, they expect to afford the costs of adaptation, at least for a while, as temperatures and sea levels rise; second, if they give in to bargaining they have the most to lose -- the lion's share of global GDP. The commitment of the poorest, in contrast, arises precisely from the fact that they cannot adapt. Small rises in sea levels, for example, will overwhelm entire nations. They have nowhere else to go -- but also, being the poorest, they have most to gain, in the shape of the same lion's share of global GDP that the richest would like to keep.

No wonder the richest countries approach Copenhagen reluctantly, with trepidation -- and the poorest go there with a glint in their eye. When the poorest countries demand that global temperature increases are limited to +1.5 degrees, they are effectively requiring that the economies of North America and Western Europe are shut down -- immediately. It's not going to happen, but what do the poorest countries have to lose -- and what is there that they can gain instead?

In the middle are China, India, and most middle income countries. They do not have too much to win or lose from bargaining. They can afford a little adaptation to climate change; ultimately they share the common interest of humanity in mitigation of climate change. But they also have least commitment.

To conclude, what makes climate change intractable at Copenhagen is that 190 countries are playing three games at once. Nested within the tragedy of the commons is a hold-up problem. Negotiating the hold-up takes the form of a game of chicken. Perhaps if we all understand this better, it will become easier to solve ...

And a happy Christmas and a prosperous New Year to all my readers!

P.S. Chicken, of course, is a game for teenagers. The adult response is: "Give me the car keys and go and finish your homework!" Don't you wish someone would say that at Copenhagen?

November 23, 2009

Student Fees: Four Myths and a Certainty

Writing about web page http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/education/8350051.stm

Student fees are in the news again. These are the top-up fees paid by British and EU students to take degree courses at British universities, presently capped at £3,225 a year. They're called "top-ups" because they help to bridge the gap between the public money that goes to universities and the actual cost of degree programmes -- which is considerably more. So, should our universities be allowed to raise their fees?

The government has announced a review. The lobbies are brushing up their arguments. Everyone has their opinions about the justice or injustice of student fees. As it turns out, fairness and economics are closely connected, but not always in the way that the lobbies think.

- Myth #1: It's unfair if higher fees deter some young people from going to university.

Let's think about the choice that people make when they decide to study at university. There is a benefit and a cost. The cost is the fee, plus the time you have to give up to study. The benefit ... well, there can be a financial benefit if you get a higher paid job as a result, and you probably will: a recent goverment survey put the average lifetime graduate premium at around £150,000. Just as important, there can be non-financial benefits. These include having more time to grow up, geting better networked, having more rounded knowledge of the world, a clearer motivation, and so on.

Just to be clear, I would never argue that money is the only thing that matters. But, along with other factors, money should matter, because higher education costs money and someone has to pay.

Add up the costs on one side, and the benefits on the other, and you should choose to study at university if the benefit exceeds the cost. Of course, not everyone tots it up in two columns and a common currency, like an accountant. Consciously or unconsciously, however, that's what is implied when we say that a young person should reflect on whether going to university is worth it or not.

In anyone's personal calculation the cost element is bound to be the private cost. Young people ask what it will cost them, not what it will cost society. But, as things are, the social cost of a degree course is a lot more than the private cost, which is the fee. The social cost is on average four times the fee, and in some courses more than that.

That has important implications. It is sometimes feared that many potential students will deterred by higher fees. That may not be true, given the size of the benefit compared with the cost -- but suppose it is. It would imply that many young people are currently opting in favour of going to university when the benefit is little greater than the private cost. A small increase in the fee would tip them against this choice. That is why they would be deterred.

Yet any small increase in the present fee will still leave the private cost far below the social cost. In other words, the claim that many young people woud be deterred from choosing university by an increase in the fee, when the fee still falls well short of the social cost, suggests that by going to university these same young people will impose a significant net loss on society.

If young people take up university places that cost more to provide than the benefit, there is a loss. Who will suffer the loss? Well, taxpayers. When money is short for nurseries, hospitals, and the care of old people, it's unfair if the average taxpayer, who is poorer than the families of most potential students, and also poorer than most graduates, should have to pay for something that gives less value than the money they have to give up.

To me this worry that many students will be deterred is not a serious concern. For most students, a degree is an excellent deal -- probably worth as much as a small house. Most would not be deterred by having to pay the social cost. The few that would be deterred, however, should be.

There is one qualification to this argument -- a serious one.

- Myth #2: But what about young people from poorer backgrounds? Isn't it unfair for them?

Potentially, yes; social justice for people who are relatively worse off should be a serious concern. Some young people have the aptitude and motivation to benefit from higher education, but their families are too credit-constrained, or too risk-averse, to support their children through three years of a degree course. I can well understand how a family contemplating the costs of sending a child to university for the first time would worry greatly about whether it would be truly worthwhile. We should definitely be imaginative in working out ways to ensure that candidates from low-income backgrounds are not disadvantaged as a result.

Here's my suggestion.

The government should make available low-interest loans to students from low-income families. The loans should both cover fees and contribute to the living costs of attending university. The repayments ought to be both income contingent and capped to ensure that nothing has to be repaid until the graduate's income reaches a certain level (for example, £15,000), and that repayments cannot exceed some modest proportion of the graduate's income above that level (say, 9%). Finally, after some period (say 25 years), any remaining debt should be cancelled.

The effect of this proposal would be to relax the cash constraint on low-income families and also remove all the risk from debt-based student finance.

Oh. Someone just told me we have that already! How cool is that. In fact, we have it for everyone, not just the ones from low-income families. Hmm. That might be making it too easy for potential students from well-to-do families. I guess that's the price we have to pay for being allowed to help the ones that truly need it.

- Myth #3: If I have to pay higher fees, I'm entitled to expect more for my money.

It sounds only fair, doesn't it? You pay more, so you should get more back. More contact hours, more personal support and guidance, more feedback.

But there's a problem. Think back to the mid-1990s, to the time before fees, when you would have paid nothing. Does that mean that, at that time, university courses cost nothing? Well, no. They probably cost just as much to provide then as they do now.

The only difference was: then, someone else was paying for what you would have got then. Who? Well, the average taxpayer. Who, by the way, was probably earning less than either the parents of most students, or the students themselves after they graduated. That's why the old system of free higher education was socially unjust; it redistributed income from poorer to richer, across both families and generations.

So, if you -- today's and tomorrow's students -- are not entitled to feel more entitled, what should you feel? Yes, there is a sense in which you should feel more demanding. You should expect more for your money. But you should not expect it from your tutors, who are being paid no more than before. You should expect more from yourselves.

What does that mean? There is a message in higher fees for those who want to go to university for no good reason: to avoid making choices, maybe, or to fill in time, or to party. Don't do it. It's not worth it. The bar is being raised. Think twice, for you may not rise above it.

If you have good reason to go to university -- you want to exercise your brain, study something worthwhile, develop your talents, and broaden and deepen your outlook on the world -- then a degree is still an absurdly valuable investment. In return for a few thousand pounds, you will walk away with a lifelong asset.

I already suggested a degree can be worth as much as a house. Most people see it as completely normal to go into debt to buy a house; they call it "getting on the housing ladder." In fact, a degree is worth more than a house because, even if you fall behind with the payments, no one will repossess it.

- Myth #4: Forty years ago I got my degree for nothing, so it's only fair that young people should too.

It's true: I got my own university education at the expense of the average taxpayer. It has been a lifelong benefit to me. Through most of my life, I have been paid considerably more than the average to do a job I love. I couldn't have done this without my degree.

Does that make it right? Does precedent mean that past unfairness can never be stopped? The argument sounds like the average taxpayer, having paid once over to make people like me richer than they are, is condemned to go on paying over and over for ever and ever. I don't think that's a good argument.

If you care about social justice, put taxpayers' money into nursery care and primary and secondary schools, which have far more power to re-engineer society than do universities. It is nurseries and schools that truly enable the talented to rise and make good citizens out of all of us and our children. And let those that will reap the benefit pay for their own university education.

- To go with the four myths, a certainty: raising student fees will not be popular.

According to a recent NUS survey, a majority of those polled was in favour of abolishing student fees; only 12% favoured higher fees.

In some ways that is a strange result. The main beneficiaries of raising student fees will be everyone in the country that pays any sort of tax -- income tax, VAT, excise duties, and the rest: in fact, just about everyone. The main losers will be the future graduate middle class, but their loss will be tiny compared with the gain from graduating with a degree. (There will also be a few that lose because higher fees deny them access to a public resource that they would fail to make good use of. I won't lose sleep over them.)

So, you'd expect the vast majority to favour higher fees. Yet, that's not what we find.

Most likely, two confounding factors are at work. One is organization. There is a well networked lobby of students and middle class parents that like the existing system for siphoning money from poor to rich. In comparison, the average citizen that suffers the loss is poorly organized and poorly networked.

The other confounding factor is the value of gains and losses. Hundreds of thousands of middle class families know they can benefit to the tune of tens of thousands of pounds from no fees or low fees for their children. In contrast, the gain to society from higher fees will be spread more thinly over millions of citizens, none of whom may feel confident of reaping a personal gain -- particularly if they have children that may become students in due course.

In the words of Raquel Fernandez and Dani Rodrik (in the American Economic Review, 81:5 (1991), pp. 1146-1155), there is "status quo bias." The defenders of minority privilege can have a louder voice than those that prefer moving towards greater justice and transparency for the majority.

In a democracy, however, social justice and transparency will sometimes have their day.

October 13, 2009

The 2009 Economics Nobels versus Big Government

Writing about web page http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economics/laureates/2009/press.html

Elinor Ostrom and Oliver Williamson have just shared the 2009 Nobel prize for economics. Unsurprisingly, the first ever award to a woman is attracting much of the media interest. Many journalists are likely to find that an easier topic than the content of their contribution.

Anyway, we'll focus on what Paul Krugman would call the wonkish stuff. What do these two share? According to the prize committee, it is their contribution to "the economic organization of cooperation."

What does that mean? On the BBC news website BBC economics editor Stephanie Flanders is quoted as saying that the judges had rewarded work in areas of economics whose practitioners' "hands were clean" of involvement in the global financial crisis. This is true, sort of. As far as I can see, neither Ostrom nor Williamson have contributed anything to recent asset price bubbles, correlated risk taking by banks, or the psychology of "It's different this time."

But it's more interesting than this. In a year when big government is all the rage, the prize committee has chosen to honour two scholars whose work cautions against big government solutions to economic problems.

I've never read anything by Ostrom; in fact, I'd never heard of her before yesterday. I feel bad about that, but I would feel worse if much more knowledgeable people like Paul Krugman (last year's Nobel laureate) and Steven Levitt (of Freakonomics fame) did not also admit to never having read her work. In order to say anything about it, I am relying partly on the Nobel citation, partly on a short interview she gave to BBC Radio 4 News last night.

Anyway, this is what I have picked up. Ostrom works on the management of common property such as land, water, and fish stocks. Economics 101 tells us that private exploitation will destroy the commons in the absence of government regulation. Ostrom's research is reported to show that there are alternatives in between private exploitation and government regulation. User communities often come up with cooperative management solutions that are less costly or more efficient than either, on their own initiative. It sounds like I should find out more.

In contrast to Ostrom's, I know of Williamson's work. I use it in my research papers, and also in my teaching. In fact, I'll be telling my final year undergraduate students about it next Monday in a lecture on the topic of "Government Failure." (The course is called The Making of Economic Policy, and I give two introductory lectures, one on how markets fail and one on how governments fail.) Williamson comes into the lecture because of his work on what he calls "the impossibility of selective intervention."

The starting point is to imagine the best of all possible worlds. We live in a market economy, and sometimes markets fail. Williamson's work shows, for example, that the very existence of firms is a response to markets not doing everything well. For some purposes it's cheaper to organize exchange within an integrated organization than through markets. Firms are these integrated organizations.

Can an integrated organization fix everything that markets can't fix? The key here is that government intervention is conceptually similar to just having bigger and bigger firms. In fact, twentieth century socialists often thought of the socialist economy as "one big firm." When markets fail, I suppose we'd all like to think the government could step in selectively, just when required and only then, and fix the failure. Then, we could always have the best of everything: market allocation, unless it fails; if the market fails, intervene to correct or replace it. That's selective intervention. Over the last century social democrats and democratic socialists have put forward many different ideas about what exactly needs fixing, but all would have agreed, I think, that selective intervention is the key. Williamson's work suggests, however, that this best of all worlds is out of reach.

Of course, Williamson is a scholar, not an ideologue, so he doesn't reach this conclusion directly. In The Economic Institutions of Capitalism (1985), for example, he asks a related question: what are the true limits on firm size? (Or, why don't we run the economy like one big firm?) He argues that replacing the market with an integrated organization always has unanticipated costs. The market, for example, provides high-powered rewards for success and penalties for failure. Intervention always impairs these incentives. We can define the benefits of intervention in advance, but not the costs. If politicians are allowed to intervention selectively, some interventions will inevitably make things worse.

Why? There are several reasons. One is the cost of good intentions: "Decision makers," Williamson writes, "project a capacity to manage complexity that is repeatedly refuted by events." Another reason is the propensity to micro-manage: Intervention always involves the exercise of power, including the power to divert resources to private goals. A third reason is the effect of "forgiveness" on effort: If a firm is losing out to market competition, there is no appeal against the verdict of customers. Managers and workers know this, so they make inordinate efforts to avoid losses. In a politicized environment, in contrast, sharing and horse-trading are much more important, so loss makers can buy political insurance against failure, or forgiveness. As a result, efforts to avoid failure are less. Finally, loss making activities are more likely to go on making losses. That's because politicization creates scope for lasting alliances based on reciprocity; loss making activities can win subsidies from profits made elsewhere and are not closed down. So, losses persist.

In short, Ostrom and Williamson point in the same direction. Ostrom is saying that big government may be less necessary than we think. Williamson is saying that, even when necessary, the results of big government will always disappoint.

This is not the same as to say that politicians should never act. If there are always unanticipated costs, there may still be benefits, and the benefits may still outweigh the total costs -- both expected and unexpected. An example is the big-government bail-outs that saved the world economy over the past year. We will be paying the bill for a long time, and the bill will be bigger than anyone thought. The fact is, it had to be done and was worth doing.

The message of the 2009 economics Nobels is not to make a virtue out of what was done from necessity. The return of big government is not a cause for celebration.

Mark Harrison

Mark Harrison

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…