All entries for April 2010

April 30, 2010

Poor Greece — Poor Us?

Greece at the mercy of "the markets." Hundreds of thousands faced with job cuts, lower salaries, and longer to work until retirement. It's hard not to feel sorry.

Equally, it's easy to understand the wrath of many Greeks: why should foreign bond holders have such power over the domestic policies of a sovereign state? Why should they accept the diktats of the IMF?

There is a simple answer. For many years, the Greek government spent far more than it raised in taxes. Why? It was the easiest way to buy votes. The problem was that the Greek government could not do it without the cooperation of others: those willing and able to lend it it.

Some of these were Greek financial institutions such as pension funds. But 80% of the Greek debt is held abroad, much of it with German and French banks. But these have walked away, taking the ball with them.

Now that the markets have called an end to the game, those who want to stand up for the entitlements of the Greek workers have to ask where the money will come from. Here are the options:

- Continue to borrow on the market -- but who will lend? The Greek debt is already at or beyond the margin of sustainability (on which more below). It is not an attractive prospect.

- If not borrow, then take. One option for the Greek government is to take from the lenders that previously enabled the years of pleasure and are now causing the pain. Taking without permision is normally called taxation. In this case it is called default. For Greece, default is all the easier because most of the lenders are abroad; they do not vote and are unlikely to throw rocks. Unilateral default has one problem: you can only do it once. After that, there is the same problem as before: if the voters want the Greek government to spend more than it raises in taxes, they must borrow. But who will lend?

- If neither borrow nor default, then print money. For most sovereign states, printing money would fix several things at once. The new money would cover the budget deficit. Then there would be inflation, but inflation would erode the real value of the debt. After that there would be a disaster, but hey ... But Greece cannot go down this road, even if it wants to. When it joined the euro, Greece gave away the right to print its own money.

- If neither borrow, nor default, nor print money, then ... raise taxes and cut spending, because there is nothing else that can be done.

These are Greece's options. In fact, the conditions that the EU and the IMF are "imposing" on Greece -- to raise taxes and cut spending -- are just what Greece must to do anyway, because there are no other choices that don't end in disaster.

Even that might not be enough. Government revenues are currently around one third Greece's GDP. If the debt heads for 140% of GDP and then stops, and must be refinanced at 10%, it follows that in future taxation must transfer 14% of GDP annually to bondholders in interest payments, and these alone will use up around 40% of Greece's limited tax capacity. Moreover, around 80% of Greek debt is held abroad, so those interest payments must shift more than a tenth of Greek GDP abroad each year -- just to cover the service on the debt, not to reduce it. The currrent EU-IMF bailout assumes that Greece's problem is liquidity. But what if it is solvency?

In that case, the future still holds the possibility of default. Given more time there will perhaps be an organized, agreed default. A rescheduling of repayments agreed with Greece's creditors will not kill Greece's credit ratings for ever, provided Greece adheres to the conditions imposed upon it.

One way of thinking about the Greek government yesterday, if not today, is that it stood at the centre of a web of obligations: legal obligations to bondholders, moral obligations to public sector employees and pensioners, and political obligations to voters. What the world has found, adding these up, is that they total far more than Greece's available resources. Something must give.

Greece holds one card, and it is an important one. If Greece goes down, so do its foreign bondholders. The German government has faced the choice between bailing out Greece and bailing out its own banks. It is interesting, and not inevitable, that the German administration has chosen in favour of Greece rather than to let Greece go and pick up its own pieces afterwards. This illustrates two things: the importance of politics, and the well known saying widely attributed to Keynes: "If I owe you a pound, I have a problem, but if I owe you a million, the problem is yours."

In all modesty, how far from Greece are we? Expectations of the British government, and what it can do for lenders, employees, the young, the old, the sick, and voters at large, have also become overstretched. Like Greece, the UK has a government that overspends, with a budget deficit of similar size relative to GDP. As in Greece, public spending is much more important to the UK economy than it should be. Even before the crisis, its importance was rising steadily; public spending accounted for nearly half of the entire increase in GDP over the period of the Blair-Brown government from 1997 to 2007. Since the start of the crisis, the growth of public spending has accelerated. Right now, public spending amounts to more than half of the UK's GDP.

In some other important ways, we are much better placed than Greece. Our aggregate debt is smaller relative to GDP, with less need for near-term refinancing. More significantly, the UK has a much greater fiscal capacity than Greece, with better coverage of tax raising institutions and less avoidance. We will be able to raise the taxes we need to finance the debt we have. And we will raise them, for another important reason: more of our debt is held at home, so lenders are also voters.

Finally, and crucially, we are not part of the eurozone. That matters, not because it will let us print money, but because it will let us recover from fiscal adjustment. The coming squeeze on spending and tax increases will put a cramp on jobs and demand from the public sector, but further depreciation against the euro and dollar will eventually rebalance the economy, allowing exports and private spending to take its place.

If there is a parallel with Greece it is not in the national picture but the regional one. For the UK as a whole, the ratio of government spending to GDP is currently a little over one half. For Ireland, Wales, and the Northeast it is between 60 and 70 percent. These regions are not only hugely dependent on public subsidies but they have no chance of renewed competitiveness through currency depreciation because, like Greece, they belong to a currency union -- in their case, the United Kingdom. What keeps them going is an unconditional year-on-year bailout from central government revenues.

My vote is not yet decided, but these are some of the reasons why I am taking seriously what the conservatives have to say about the economy today. Darling called the first phase of the crisis far more astutely than Osborne, and labour deserves credit for that. I am not convinced that more of the same will take us into a recovery.

April 16, 2010

Privatized Keynesianism: Rebirth After a Life That Never Was?

Writing about web page http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/122498671/abstract?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0

"Privatised Keynesianism: An Unacknowledged Policy Regime," published in the British Journal of Politics & International Relations11:3 (2009), pp. 382-399 by my Warwick colleague Colin Crouch, has been deservedly recognized and cited by scholars and journalists. The paper starts from the idea that it is a problem to maintain stability and consumer confidence under capitalism. These were secured for thirty years after the war by Keynesian demand management. After that, Crouch writes:

In those countries where capitalism was moving into full partnership with electoral democracy, it was acquiring a new vulnerability. In a fully free market, wages and employment were likely to fluctuate; would workers, who were dependent on their incomes for their level of living and lacked the cushion of wealth of propertied classes, be confident enough to consume at levels adequate to enable capitalists themselves to sustain confidence to invest and maintain profit levels? Would the very characteristics of the market that constituted its strength—flexibility, especially of labour—undermine its own ability to thrive? It should be noted that we are not here talking of the market producing social problems of insecurity in workers’ lives—that might be dealt with by an adequate welfare state—but of its producing problems for itself through its own dependence on workers’ willingness to maintain and increase their consumption. It can be assumed that the level of living at which social policy will sustain purchasing power will be below that needed to sustain an expanding, consumption-driven economy.

And he continues:

In the 1940s it had seemed that only state action could solve this problem for the market. But now, absolutely in tune with neo-liberal ideology and expectations, there was a market solution. And, through the links of these new risk markets to ordinary consumers via extended mortgages and credit card debt, the dependence of the capitalist system on rising wages, a welfare state and government demand management that had seemed essential for mass consumer confidence, had been abolished. The bases of prosperity shifted from the social democratic formula of working classes supported by government intervention to the neo-liberal conservative one of banks, stock exchanges and financial markets.

I have thought about this a lot recently, partly because my students love it -- and reproduce it for me in their essays! I have to say I don't buy it -- at least not in this form. Why am I sceptical? Well, Crouch's argument seems to be that capitalism is vulnerable to underconsumption. From 1945 through the 1970s, the argument goes, the British government ensured demand was sufficient. After the 1970s, Crouch suggests, government retreated and banks stepped in. In his eyes, British capitalism survived on credit.

The big thing here that is clearly true is that as the public debt declined, household debt rose. My problem is with the counterfactual. Implicitly, without government spending in the first phase, and credit expansion in the second, there would have been a problem: not enough demand. In the first phase, that is for most of the period up to the 1970s, it's clear that British capitalism actually suffered from too much demand; that's why there was rising inflation. In the second phase, after the 1970s, the government didn't so much step out of the picture as try to limit demand more fiercely (and hamfistedly at first), eventually delegating the job to the Bank of England. In this phase I don't really see any evidence that British capitalism was going to fall into decline if we hadn't been able to lend lots of money to the workers that they couldn't afford to pay back.

With less household borrowing and less equity realization, what would have happened? Most likely, interest rates and the exchange rate would have been a little lower, and exports would have been a little higher. With more export competitiveness, our manufacturing sector would have declined a little more slowly (and our universities might have expanded a little more). That's about it. Oh, and I guess we would be in slightly better shape today.

Ironically it is only now, in the current recession, after a huge credit crunch and collapse of private demand, that privatized Keynesianism has truly come to life. Hence, in my view, its rebirth, after a life that never was. Here is some evidence, which you'll note is tri-partisan:

-

BBC, July 23, 2009: Chancellor Alistair Darling has urged banks to lend more to small firms, during a meeting with banking bosses ... Alistair Darling has said he is "extremely concerned" that banks may be charging firms too much for loans.

-

Reuters, October 26, 2009: British retail banks should stop paying big cash bonuses and use the money instead to support new lending and contribute to an economic recovery, opposition Conservatives’ finance spokesman George Osborne said on Monday.

- The Guardian, February 23, 2010: A new government should tear up "ineffectual" lending agreements with Britain's taxpayer-owned banks and force them to lend billions of pounds more to small and medium sized businesses, Liberal Democrat Treasury spokesman Vince Cable said today.

Thanks to Colin Crouch, we know what to call it: Privatized Keynesianism. It is Keynesian because it uses debt finance to add to aggregate demand. It is privatized because the debt is private and stays off the government's books.

Now, the question is: Is privatized Keynesianism a good idea for today? Hmm. Why are we in the mess we are in? I think it might have been that we had too much private debt in the first place, so banks lent too much to firms and households that had no chance of repaying their debts unless house and stock markets floated ever upwards; and because banks did not keep enough in reserves. Where are we now? House and stock prices are still too high, and they are rising. And the solution these politicos favour is ... more private debt! The bankers are letting us down! They should be out there trying to persuade us to take out more loans! They should be keeping less in reserves!

You couldn't make it up, could you?

At this point I am going to offer one of those dire aphorisms that runs: "The only thing worse than X is -X." I apologize in advance, but there is no alternative, so here it is:

- The only thing worse than having bankers making lending decisions is to have politicians making lending decisions.

This does not mean I am complacent about the need for better financial regulation. Politicians have a role to play, and it is in setting prudential rules, limiting guarantees to retail depositors, and removing the incentives for banks to grow "too big to fail." That is a lot, but that is all. Politicians should not be making lending decisions! That is the bankers' job; let them do it.

April 01, 2010

On the Floor: What is Stopping Our Economy Falling into the Basement?

Writing about web page http://johnbtaylorsblog.blogspot.com/2010/02/one-year-later-and-more-evidence-that.html

A couple of months back, John Taylor made the point that the U.S. recovery is being led by the private sector. The vaunted $787 billion fiscal stimulus package passed by Congress has played no role. This is for a simple reason: it hasn't happened yet. This led Taylor, rightly, to wonder what will happen when it does come on stream, most likely in the middle of the recovery.

Now that the 2009 Q4 figures are available, it is interesting to ask the same question of the UK economy. Recovery has started, or at least the decline has stopped. Where is the improvement coming from? Is it coming from private demand or public spending? Is it coming from home or abroad?

The chart shows the changes in the main components of GDP, in real terms, since 2008 Q1:

Source: ONS. G is general government consumption, NX is net exports, DInvent is the change in inventories, C is household consumption, and GFCF is gross fixed capital formation. Omitted are final consumption not by households, and net acquisitions of valuables.

The main picture is clear. Domestic private demand has collapsed. Until recently our economy was being held up partly by government consumption -- and even more so by foreign demand. (You might be surprised by that, given recent doom and gloom about the UK balance of trade. And there is a downside, which we'll come to.) The fact is that, from mid-2008 to mid-2009, the biggest support for the UK economy came from net exports.

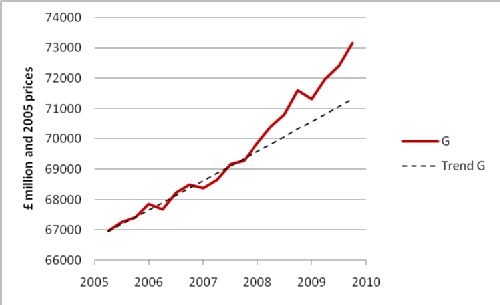

Right now, however, government consumption is what is holding the economy up. I think the John Taylor question for the UK would be: Is the action on public spending currently any more than was already in the pipeline before the crunch? In other words, is active intervention or passive drift at work? This question is answered by the next chart, which strongly suggests active intervention:

Source: ONS. G is general government consumption. The trend is log-linear, calculated over 2005 Q1 (i.e. the last quarter of the previous Parliament) to 2007 Q4 (i.e. the last quarter before the GDP decline set in).

The chart shows clearly that, from the onset of the crisis, public spending began to move sharply upward from the trend established over the previous quarters going back to the last general election.

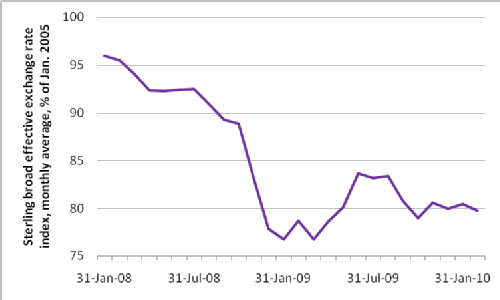

Another question is: How can we account for the net stimulus from trade, at a time when global demand was collapsing as fast as or faster than demand at home? There are two candidates: the foreign fiscal stimulus, and the domestic monetary stimulus. The deciding factor here is the real exchange rate. If global demand did the trick, boosted by the foreign fiscal stimulus that the G20 coordinated from the G20 last year, then the improved real trade balance should have been accompanied by an unchanged or rising real exchange rate. If it was quantitative easing pursued by the Bank of England, then we should see a declining real exchange rate. In the latter case, we saved ourselves by grabbing more than our share of global demand through competitive devaluation.

The next chart shows it was the Bank of England and competitive devaluation that did it.

Source: Bank of England. The series plots the broad sterling effective exchange rate monthly average.

The 30% decline in the real exchange rate through 2008 implies UK monetary policy was doing the larger share of the work. We grabbed a lifebelt, while others were beginning to drown -- Greece, lashed fast to the Euro, among them.

At the end of 2008, however, the depreciation of sterling came to an end. As a result, we are now even more dependent than we were a year ago on public consumption to hold up the economy. As the first chart shows, since the recovery began, the contribution of the trade balance has ceased to be positive. While household consumption and inventories are now showing small positive contributions, fixed investment is falling again. It's not a good picture.

What does this mean, given the public spending cuts now in prospect, whoever wins our coming elections? In principle, the real effect of public spending cuts on aggregate demand should not be entirely negative; lower government consumption should bring down interest rates and this should stimulate Britain's export sector through further currency depreciation. The trouble is that interest rates are already close to zero, and cannot fall further. Like the real economy itself, interest rates are on the floor but, unlike the real economy, cannot fall into the basement. For this reason it's hard to see how public spending cuts will translate quickly into improved prospects for recovery.

I understand that Britain has already too much public debt, of course, and will have to add to it in order to maintain public spending. We cannot do this without the cooperation of the lenders! This is why it is essential to plan for deficit reduction over the medium term.

At the same time, it is clear that the spending cuts in prospect are likely to cause double pain: not only a reduction in the level of public services, but also damage to the recovery of the real economy. Whatever government is in power, these are reasons to be very, very careful.

Mark Harrison

Mark Harrison

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…