All entries for April 2022

April 26, 2022

'Following Living Things and Still Lifes in a Global World': Reflections on the conference

Writing about web page https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/hrc/confs/flt/

In this post, Cheng Heand Camilo Uribe Bottalook back at and reflect on their conference 'Following Living Things and Still Lifes in a Global World', which took place in mid February.

Figure 1 Olaus Magnus, Carta marina et descriptio septentrionalium terrarum (Marine map and description of the Northern lands), 1539, source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Carta_Marina.jpeg

The first panel centres around the way of approaching materials, and involves various kinds of materials including artefacts, plants and animals. The first paper by Erika de Vivo unfolded the cultural construction of Sámi people during the contacts between Sápmi (ancestral homeland of Sámi in Northern Fennoscandinavia) and Italy between the sixteenth and early twentieth centuries. The second paper by Jaya Yadav traced the plantation of Darjeeling tea in British colonial trade and its re(creation) of identity till today. The third paper by Charlotte M. Hoes looked at animal trade particularly through an animal trading company in Germany in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The three papers cover quite different subject, geography and time period. What amazed us is that they focused on a single type of material and their mobility. This means not only to be object-focused but also to follow their life from the start of the interaction between them and human beings, to their movement (materials might be moved physically and represented in different contexts via different media) and how their meanings changed during their life paths.

Apart from the mobility that all three papers emphasise, there was another important question particularly discussed in the Q&A session: how to determine the line between ‘live’ and ‘still’ materials, or, is it worth classifying materials this way? This is especially representative in the case put forward by Erika, that human remains are apart of materials that contributed to the shaping of the images of Sámi people. This also applies to tea and animals, especially when they became artifacts or products. The agency of materials is always an interesting aspect to consider when it comes to interpreting their meanings. In short, the first panel set a good start for the following discussion and sharing of ideas.

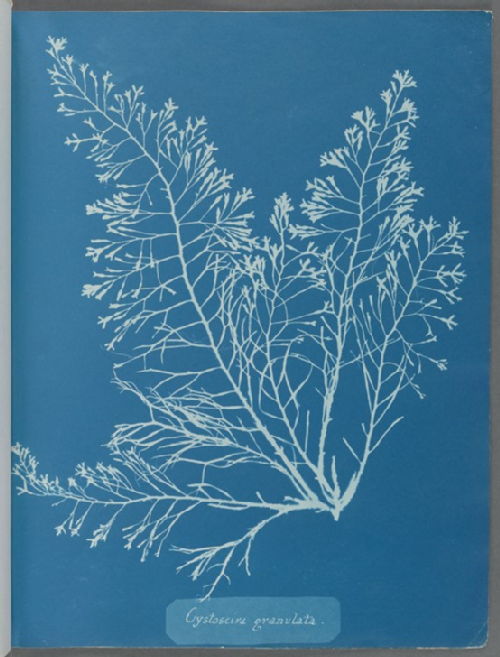

Figure 2 Anna Atkins, 'Cystoseira granulata',1844-45, in Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, The New York Public Library Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-4b02-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

In the afternoon, we started with Panel 2, which took a further step from panel 1, with three papers looking at plants only. The first paper by Anna Lawrence explored the cut-flower trade in the nineteenth-century Britain, focusing on the life of flowers before and after becoming commodities. The second paper by Annabel Dover looked at the first photographic book that contains 411 contact prints of algae collected by the botanist and photographer Anna Atkins (1799-1871) on the Kent coast and was published in 1843. The last paper by Maura C. Flannery looked at the Sicilian botanist Paolo Boccone (1633-1704), who developed techniques for making nature prints from the specimens.

All three papers touched upon the question of the relation between the plant itself and its visual representations. This is connected with one of the aspect that the conference concerns: are the material and its visual representations always discrete? These papers provided excellent examples showing that the line between the two could be blurred. Another point that the papers shared common ground with each other was the blurred boundary between the identity of the plant as a living thing in nature or as an artefact that involves human intervention. And similar to the papers in panel 1, this is related to the mobility of plants, in the sense that different stages of a plant’s life provide flexible space for assigning meanings.

The conference continued with the Panel 3, the last one, with three papers looking at animals and its different representations and interactions with humans, both in a living and in a “still-life” state. The first paper by Amanda Coate followed the life and death of an elephant in Britain and Ireland in the Seventeenth century, focusing on the animal-human relations and interactions. The second paper by V.E. Mandrij looked at the artistic production of artist Otto Marseus van Schriek and more specifically in the technique of butterfly imprints and the collecting, trading and scientific activities related to this. The last paper by Catherine Sidwell looked at the representation of birds in the British domestic interior design during the Victorian era and the different uses of their feathers, forms and colours.

Figure 3. Otto Marseus van Scrieck. Forest still-life with butterflies, snake, frog and dragonfly. 17th Century. Private Collection, Switzerland. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Otto_Marseus_van_Schrieck_-_Forest_still-life_with_butterflies,_snake,_frog_and_dragonfly.jpg

The three papers had in common that they took an animal as the starting point of their analysis: elephants, butterflies and birds. But they developed their arguments through different paths, presenting distinctive approaches to the living and still state of animals when their histories intersect with humans, whether alive, death or in a represented form. These papers provided an excellent analysis of the other-than-human and human interactions in what Amanda Coate called a “shared space” between species. This panel also versed about the agency of animals and how their presence in human everyday life evidenced interactions and connections in different contexts. In this panel, a topic that was widely discussed was the nature of an animal, living and dead, and its transitions between one state and the other, from a scientific object to an artistic one and the conditions in between. It revealed the complex nature of animals and our relations with them.

Finally, the conference ended with a keynote by Professor Helen Cowie about two anteaters in Madrid and London between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Cowie’s approach to these two animals from an animal biography perspective did a great job creating synergies with some of the main ideas that were discussed by the different papers in this conference. Although the arrival of both animals to Spain a Britain took place under different circumstances and different societies, their presence in Europe represented a living ambassador for animal species little known in Europe and triggered thought-provoking debates that Professor Cowie addressed in her presentation.

Assessing the receptions of these animals in Spanish and British societies, Cowie considered their broader cultural and scientific contexts: the logistics of the animal trade, the Transatlantic network that permitted the anteaters and the knowledge about them to cross the Atlantic, the technologies of representation that permitted to reach different audiences. Finally, Cowie’s presentation enlarged the debates that were part of this conference to colonial and imperial science, knowledge and authority.

Figure 4. Rafael Mengs Workshop (probably Francisco de Goya). His Majesty’s Anteater. 1776. Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales. Madrid. https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/la-osa-hormiguera-de-su-majestad-18th-c/YAEuV7WNHQeoYg

April 08, 2022

The Supernatural and Suffering in Research: Reflections from our Speakers (Part Two)

Writing about web page https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/hrc/confs/supernatural/

In this fifth blog post for The Supernatural: Sites of Suffering in the Pre-Modern World, HRC doctoral fellows Francesca Farnelland Imogen Knoxare back with more reflections from the speakers on how their research intersects with the conference themes. This should give a flavour of the variety of topics that will be explored at the conference! Please register for free here.

What drew you to the supernatural?

Cameron Cross - I first encountered research on the supernatural during my undergraduate year abroad in Heidelberg. I took a fascinating course which translates to ‘Love Potions and Pacts with the Devil: Magic in Medieval [German] literature’. While reading up for the course, it became apparent that there was a considerable gap in current research about how the supernatural can be used to oppress people and characters. I knew I had found the area I wanted to research full-time when I still had questions about that theme still swirling in my head three years later. Two degrees later, I am researching how the divine supernatural dehumanises characters in medieval French and German literature.

Meaghan Allen - I have always been fascinated by the supernatural and fantastic. As a child I collected fairy paraphernalia and loved to read ‘dark’ stories for my book reports. Now, many year later, I am pursuing my passion for the paranormal for my PhD thesis and research, a project that contemplates the complex manifestations of the supernatural and preternatural in medieval hagiography and contemporary horror, particularly (though not exclusively) Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Penny Dreadful.

Buffy the Vampire Slayer

What role does suffering play in your work?

Cameron Cross - I am mainly based in Dehumanisation Studies these days, but my research intersects significantly with Disability Studies and Gender Studies. Looking at the dehumanisation of disabled and/or female characters is what most of my research entails at the moment. Often then involves looking at violence, misogyny and ableism. So, it is safe to say that suffering is a cornerstone of my research. I’ll trust readers not to over-analyse that too much.

Meaghan Allen - Suffering and pain are the main themes in my research as they are the most tangible themes that speak to one another in medieval virgin martyrs lives and contemporary horror. My main question is why? Why do we as humans love stories where bodies, especially female bodies, are put on display to then be battered and beaten alongside immense displays of psychological and emotional torment? What does this suffering do and why do we still tell these stories? These are large questions that do not necessarily have a single answer, but they are the motivating factors in my research.

My friend Elo and I have an on-again-off-again podcast called ‘Modern Medieval: The Podcast’ that can be found on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and basically anywhere you listen to podcasts. Our twitter is @medieval_modern

I have also written an article for the Final Girls collective about rape revenge films. I am also recording an episode for the Final Girls Podcast on March 28, 2022 about teen & internet horror. I am not sure when it will release, but it is pending.

Do you have a favourite supernatural story or anecdote?

Meaghan Allen - The British Library has a fantastic book series called the Tales of the Weird that are all fantastic collections of the supernatural, paranormal, and just plain weird. But if I had to answer honestly, I would say my favourite ‘supernatural story’ is Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

Cameron Cross - This is a tricky one. I think my favourite research anecdote is discussing the Old French Fabliaux, a corpus of texts which are as bawdy as they are marvellous. Without going into too much detail, there are one or two stories with wishing magic in them, and it is a rare example of women using the supernatural to outsmart male protagonists and getting away with it. Another are mythical creatures in medieval bestiaries. I took a course on bestiaries, thinking animals and allegory would be an interesting topic to study. I certainly did not expect to find instructions on how to catch a unicorn.

Anon, The Brideling, Sadling, and Ryding of a rich Churle in Hampshire (London, 1595), EEBO

Francesca Farnell - One of my favourite supernatural tales is about one late sixteenth-century wise woman called Judith Philips who could use her mystical powers to summon the queen of fairies - except that all the supernatural elements of this story were entirely fictitious. Judith was, in fact, a con artist who swindled an old miser and his wife, but the specific method by which she did so is what makes her story so entertaining. One day after happening upon this wealthy, but very gullible, old miser, she donned the disguise of a wise woman and promised him and his wife that she could earn them fortunes by consulting with the queen of fairies on their behalf but, to help summon her, the husband first had to allow himself to be saddled like a horse and ridden up and down the garden by Judith. Then they would then have to lie grovelling on their bellies for three hours while Judith met with the fairy queen. After some hesitation, the couple duly did what Judith commanded, while she went inside and stripped the house of its contents. To top it off, she then posed as the Fairy Queen by wrapping herself in a white smock and brandishing a stick, and revealed herself to the couple once more before vanishing away - making off with the couple’s finest linen, several expensive candlesticks, five ‘angels of gold’ and a further fourteen pounds (which, according to the National Archives, would be approximately £2,000 in today’s money). It was several more hours before the couple realised they had been duped.

Imogen Knox - The supernatural story that always stays with me is one that appears as an appendix to the 1681 pamphlet A Strange and Wonderful Relation of Margaret Gurr. After describing the possession of Margaret Gurr, the author John Skinner moves onto another story, that of seventeen-year-old Henry Chouning, of Hadlaw, Kent. One day, while venturing out into his master’s grounds, he encountered ‘a spirit in the form of a greyhound’. Henry was very alarmed when the greyhound told him ‘you must go into Virginia’. This exchange so affected him that he ‘came home in a great fright’ and he grew melancholy. It’s unclear why Henry was so disturbed by these events, other than the fact that he had encountered a talking dog! Subsequently he experienced ‘strange’ temptations, including the desire to go to sea, presumably following the dog’s advice to go to America. With Dr Skinner’s assistance, he apparently completely recovered, and doesn’t seem to have met with any other talking animals afterwards.

David Lambert

David Lambert

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…