All 2 entries tagged Trial

View all 11 entries tagged Trial on Warwick Blogs | View entries tagged Trial at Technorati | There are no images tagged Trial on this blog

May 24, 2015

Murdoch's Madras ancestor

In February 2015 the US Justice Department dropped an investigation into possible corruption at News Corp, after the UK phone-hacking and accusations that public officials had been paid for news stories. In May 2015 stories about alleged corruption in Nepal were the subject of a BBC documentary, in which it was suggested that money intended for relief efforts after the earthquake might be siphoned off. These two apparently unconnected stories are linked by an early nineteenth century scandal, involving News Corp’s boss Rupert Murdoch’s great great great grandfather, Robert Sherson, an East India Company official who was accused of embezzling money from a relief effort after a famine and then violent storms hit Madras in 1807. We have Sherson’s side of the story, since he had access to the press, and published several vindications of his conduct.

Robert Sherson had been appointed as Superior in the Grain Department, and supervised the food intended for the relief of 300,000 inhabitants affected by a famine. On 10 and 11 Dec. 1807 a violent storm tore the roof off the grain store, leaving it vulnerable to ‘the depradations of the starving multitude’. Sherson ordered a survey of what was left and ‘incautiously’ signed the estimate, ‘not suspecting public servants in whom he himself had been in the habit of confiding largely upwards of six years’. But the estimate was not believed by Sherson’s bitter enemy in Madras, Mungo Dick, with whom he had a long-standing dispute and, unluckily for Sherson, Dick had power over him as one of the members of the Committee overseeing his actions. Dick’s investigations concluded that the estimate of losses had been deliberately inflated and refused to accept that the mistake was an honest one. A Committee of Enquiry was set up by Governor Sir George Barlow, who, ‘the dupe of designing men’, appointed Dick as its chairman. The result was that on 10 Feb. 1808 Sherson was dismissed from his offices (he was deputy Customs Master, Assay Master, Director of the Government Bank, posts worth £4800 pa) under the charge of having fraudulently sold grain to the value of £12,000. Sherson was also accused of selling grain at higher prices than were authorised by the government and hence profiteering from the famine; and there were later accusations that he had attempted to bribe his assistant, a Mr Clarke.

Sherson’s defence was that he had done all he could to ensure an accurate estimate of the store had been made as quickly as possible after the story; and he refuted the charge of embezzlement, which rested on accounts drawn up by ‘the Mutsuddee or Hindoo Accountant’ who was Dick’s ‘creature’ and had allegedly doctored the accounts: ‘every one …knows the facility with which they may be mutilated. That nothing is more easy than by a dot or a scratch to add an hundred or a thousand even’ to the sums.’

When Sherson's case eventually came to court in 1814, the Supreme Court in Madras threw it out, arguing that frauds might have been perpetrated without his knowledge and that, in the opinion of the Lord chief Justice, ‘the whole amounted to nothing'. Another justice declared that if the matter had come before a British court Dick would have been jailed ‘as a perverter of justice’ and that he strongly suspected the accounts used against Sherson had been forged. Indeed, he thought it ‘astonishing, that [the Indian] Government could have listened to such a charge against a good and worthy servant, founded on infamy, fraud and conspiracy’. A third judge thought there was ‘not a scintilla of evidence beyond the opinion of Mr Cooke, founded on hearsay’. Sherson should leave court, he said, ‘freed from all suspicion of having failed in any manner whatever in his duty to his employers’. He was eventually reinstated and in 1815 the East India Company even voted him a present of 20,000 pagodas as recompense for his protracted suspension from office, and sent him back to India ‘with credit’.

The accusation against Sherson has all the hallmarks of a man with a personal grudge using a good opportunity to strike at a rival. The smear of corruption hung over him for a long time before being dispelled (and even after the judges’ ringing endorsement, suspicions about his earlier corrupt activity continued to circulate). On the other hand, Sherson had access to the press to clear his name and he also had powerful backers in the British Parliament. Seven years after he had been suspended, a Member of Parliament, Alexander Novell, waged a sustained campaign to have Sherson’s name cleared. The importance of access to politicians and the press may have been a lesson the family learnt well.

January 10, 2015

Satire, Corruption, and Religious Parody

The extent to which free speech includes a right to offend religious sensibilities is now being much debated in the light of the murder of French satirists at Charlie Hebdo in Paris.

The extent to which free speech includes a right to offend religious sensibilities is now being much debated in the light of the murder of French satirists at Charlie Hebdo in Paris.

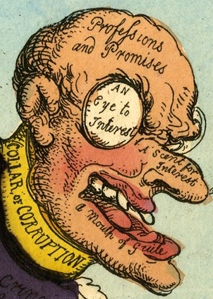

Similar issues were raised in 1817 by the prosecution of the British radical publisher and writer William Hone for parodying Christian worship in his satires against what he saw as widespread corruption in the period after the end of the Napoleonic wars.

Hone published three parodies of the creed, litany and catechism, using satire in order to press the case for the reform of corruption. The Sincecurist’s Creed, for example, parodied the code of religious belief to mock those who seemed to be paid by the state for work they did not do and yet voted religiously with the government:

WHOSOEVER will be a Sinecurist: before all things it is necessary that he hold a place of profit.

Which place except every Sinecurist do receive the salary for, and do no service: without doubt it is no Sinecure.

And a Sinecurist's duty is this: that he divide with the Ministry, and be with the Ministry in a Majority

Hone admitted having ‘an irresistible propensity to humour’. But the government clearly did not share his sense, since it charged him with blasphemy for each of the three tracts. At the heart of the government’s position was the principle that Scripture should be ‘never used for secular purposes’. Hone, defending himself throughout the three extremely gruelling trials, saw himself as a martyr for free speech. He argued that ‘if there was ridicule, those who rendered themselves ridiculous’ could not complain of libel; and that there was a long history of religious texts being used for parody (indeed, he accumulated a very large collection of such texts, stretching back to the Protestant reformation of the sixteenth century). He included visual parody in his catalogue. He also suggested that there were two types of parody: ‘one in which a man might convey ludicrous or ridiculous ideas relative to some other subject; the other, where it was meant to ridicule the thing parodied. The latter was not the case here, and therefore he had not brought religion into contempt’. He also suggested that the government was extremely hypocritical, since one of its own cabinet ministers, George Canning, had recently parodied a religious text for political purposes. Hone produced text after text in court to prove his points and was found not-guilty in each of the three trials.

Hone continued to use satire to attack corruption, though his next most important – and best-selling - publication parodied a nursery rhyme rather than Scripture to make its point. The House that Jack Built (1819) lampooned the government for building a corrupt House; but it also featured a picture of the printing press as ‘THE THING’ which could ‘poison the vermin’ who plundered the wealth of the nation.

Hone, ironically, became more religious in his later years and, aware of the offence it caused, did not use religious satire again. But the very long lists of religious parodies that he produced in court stood to highlight how important religious parody was to the Protestant tradition. Luther himself parodied the Psalms, as had eminent reformers in England. As Hone put it, parody ‘had been followed by the most venerable and respected characters this country ever produced’.

Mark Knights

Mark Knights

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…