All 2 entries tagged Parliament;

No other Warwick Blogs use the tag Parliament; on entries | View entries tagged Parliament; at Technorati | There are no images tagged Parliament; on this blog

November 09, 2021

Parliamentary Lobbying as a 'High Crime and Misdemeanour'

The debate over Tory MP Owen Paterson’s lobbying activities, following on from former Tory prime minister David Cameron’s lobbying on behalf of Greensill Capital, and the large number of Covid-related contracts awarded to friends of Tory MPs, has turned attention to the measures preventing MPs from indulging in the pursuit of their own interests or the interests of private companies rather than of the public that elected them. In particular, the rules governing MPs’ financial interests have come under scrutiny, something seemingly made more urgent by the disclosure that another serving Tory MP and former cabinet minister, Sir Geoffrey Cox, allegedly earned almost £1m working for the offshore tax haven, the British Virgin Islands, reportedly to defend the island’s authorities against a corruption probe.

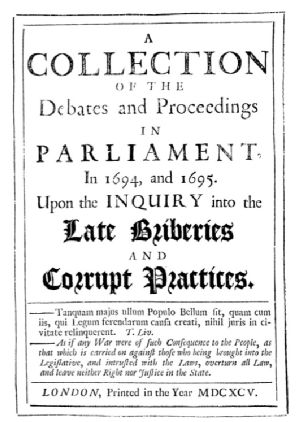

In the House of Commons debate about Paterson on 3 November 2021, Chris Bryant, the chair of the Committee on Standards, and a number of other MPs invoked 1695 as the year in which rules on lobbying were first formulated. The key resolution came on 2 May 1695 when the House of Commons resolved that ‘the offer of money, or other advantage, to any Member of Parliament for the promoting of any matter whatsoever, depending or to be transacted in Parliament, is a high crime and misdemeanour and tends to the subversion of the English constitution’. So this blog will explore why 1695 deserves to be remembered. One reason is that, just like now, it involved a combination of domestic and colonial interests.

The first MP to fall in the scandals of 1695 was no less than the Speaker of the Commons, Sir John Trevor (who was also a prominent lawyer and judge). On 7 March the House heard that it ‘was said both public and private business came to market there and neither could be done unless paid for’, so the Commons appointed a committee in order to investigate. When the committee reported its findings, Trevor was expelled from the House for accepting 1000 guineas from the City of London. This was to facilitate the passage of a bill which essentially sought to protect the City after it had repeatedly raided a fund for orphans and used the money to cover its own financial deficits. A smaller sum had also been paid to another MP, John Hungerford, who chaired the orphans bill committee. He, too, was expelled from Parliament. But these attacks were related to another scandal which was the one that pushed the Commons into making its resolution.

The roots of the second 1695 scandal lay in the commercial interests of the East India Company which had enjoyed a royal charter giving it a monopoly to trade in the east. Following the recalibration of the powers of the Crown, as a result of the 1688 revolution, the Company now needed a parliamentary charter instead. It had a lucrative trade but faced opposition from commercial rivals who wanted the monopoly abolished. The Company was thus prepared to pay large sums to win MPs over; and MPs were themselves involved in lobbying on the Company’s behalf.

An internal power struggle within the East India Company led to a critical internal report in March 1695 which made damaging revelations about irregular payments at the time of the charter renewal. This sparked a Commons committee that found that £90,000 (worth around £10m in today’s values) had been set aside by the Company for ‘private service’, or, in other words, to buy favours covertly. A joint Commons-Lords committee was set up to investigate the allegations of corruption and this found that in 1693 Sir John Trevor had received 200 guineas for his part in securing a new charter for the East India Company in late 1693. But this sum paled into insignificance compared to the huge amount distributed to, and in part by, other MPs. A key figure in the distribution of this largesse was Sir Basil Firebrace, an unscrupulous wine trader who had previously faced several allegations of corruption.

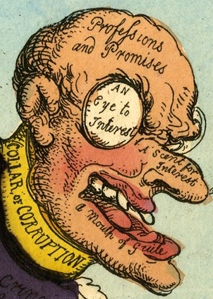

Firebrace was poacher turned gamekeeper, since he had previously been prominent among the East India Company’s critics; but he had been bought off by the wealthy goldsmith Sir Thomas Cooke, another MP, who also acted as the Company’s Governor during the charter renewal process. Firebrace had set about trying to bribe other MPs. Besides Sir John Trevor, he also paid Henry Guy, the secretary to the Treasury; Thomas Coulson, who had been given an extraordinarily favourable contract (and the suspicion was that this was also intended to profit another MP and leading Tory, Sir Edward Seymour); and in the Lords, via an intermediary, no less a person than the Duke of Leeds, the first man called a ‘prime minister’, one of the founders of the early Tory party, and, in 1695, still a man of influence as the Lord President of the Privy Council. The duke, better known by his earlier title of the earl of Danby, had been accused in the 1670s of systematically bribing MPs in order to create a party of supine members who would do the government's bidding. Now, corruption was to be his downfall.

The duke was said to have been offered almost £6000 (in today’s values, a little short of what Geoffrey Cox is said to have earned working for the BVI) to secure the new charter. Leeds at first denied any wrong-doing; and then clumsily tried to return the money to the Company. The House of Commons, dominated by his political enemies, resolved on 29 April 1695 to impeach him on corruption charges. Three days later the Commons passed its resolution against lobbying. Copies of the parliamentary inquiry were sold on the streets so that ‘patriots’ could read ‘how the country may be bought and sold by those which should preserve us’. Leeds tried to vindicate himself with several pamphlets that put his case, but his long political career was ended.

The scandal successfully smeared the Tories with a charge of corruption; but it did not put an end to lobbying scandals which continued throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Perhaps the one with the most obvious contemporary parallels concerned the MP and lawyer, Isaac Butt (later leader of the Home Rule movement in Ireland), who took money from an Indian prince to advocate for the return of territory annexed by the East India Company. Butt denied a breach of privilege, saying that he was the victim of ‘as vile and unprincipled a conspiracy as was ever brought to bear against a Member of this House’ and complained vigorously about the justice of the process being used against him (prompting protracted wrangling about the proper procedure to investigate an MP) [BREACH OF PRIVILEGE. (Hansard, 22 February 1858) (parliament.uk)]. Although exonerated from influencing parliamentary proceedings, Butt’s case raised concerns about the role of lawyers acting as advocates at Westminster rather than in the courts. As The Times put it on 8 March 1858 ‘Can we wonder that our wealthy subjects in Asia are filled with a profound conviction that our boasted purity of Parliament is but a farce?’ The result of such pressure was a further Commons resolution on 22 June 1858 ‘That it is contrary to the usage and derogatory to the dignity of this House, that any of its Members should bring forward, promote, or advocate, in this House, any proceeding or measure in which he may have acted or been concerned, for or in consideration of any pecuniary fee or reward.’ Two resolutions, over a hundred a fifty years apart, essentially affirmed the same principle against lobbying Parliament. Over a hundred and fifty years on from the last one, we seem to need it said again by the House (rather than just set out in a Code of Behaviour) and extended to cover lobbying ministers and accepting a second job that creates, or is seen to create, a conflict of interest with the public good.

May 24, 2015

Murdoch's Madras ancestor

In February 2015 the US Justice Department dropped an investigation into possible corruption at News Corp, after the UK phone-hacking and accusations that public officials had been paid for news stories. In May 2015 stories about alleged corruption in Nepal were the subject of a BBC documentary, in which it was suggested that money intended for relief efforts after the earthquake might be siphoned off. These two apparently unconnected stories are linked by an early nineteenth century scandal, involving News Corp’s boss Rupert Murdoch’s great great great grandfather, Robert Sherson, an East India Company official who was accused of embezzling money from a relief effort after a famine and then violent storms hit Madras in 1807. We have Sherson’s side of the story, since he had access to the press, and published several vindications of his conduct.

Robert Sherson had been appointed as Superior in the Grain Department, and supervised the food intended for the relief of 300,000 inhabitants affected by a famine. On 10 and 11 Dec. 1807 a violent storm tore the roof off the grain store, leaving it vulnerable to ‘the depradations of the starving multitude’. Sherson ordered a survey of what was left and ‘incautiously’ signed the estimate, ‘not suspecting public servants in whom he himself had been in the habit of confiding largely upwards of six years’. But the estimate was not believed by Sherson’s bitter enemy in Madras, Mungo Dick, with whom he had a long-standing dispute and, unluckily for Sherson, Dick had power over him as one of the members of the Committee overseeing his actions. Dick’s investigations concluded that the estimate of losses had been deliberately inflated and refused to accept that the mistake was an honest one. A Committee of Enquiry was set up by Governor Sir George Barlow, who, ‘the dupe of designing men’, appointed Dick as its chairman. The result was that on 10 Feb. 1808 Sherson was dismissed from his offices (he was deputy Customs Master, Assay Master, Director of the Government Bank, posts worth £4800 pa) under the charge of having fraudulently sold grain to the value of £12,000. Sherson was also accused of selling grain at higher prices than were authorised by the government and hence profiteering from the famine; and there were later accusations that he had attempted to bribe his assistant, a Mr Clarke.

Sherson’s defence was that he had done all he could to ensure an accurate estimate of the store had been made as quickly as possible after the story; and he refuted the charge of embezzlement, which rested on accounts drawn up by ‘the Mutsuddee or Hindoo Accountant’ who was Dick’s ‘creature’ and had allegedly doctored the accounts: ‘every one …knows the facility with which they may be mutilated. That nothing is more easy than by a dot or a scratch to add an hundred or a thousand even’ to the sums.’

When Sherson's case eventually came to court in 1814, the Supreme Court in Madras threw it out, arguing that frauds might have been perpetrated without his knowledge and that, in the opinion of the Lord chief Justice, ‘the whole amounted to nothing'. Another justice declared that if the matter had come before a British court Dick would have been jailed ‘as a perverter of justice’ and that he strongly suspected the accounts used against Sherson had been forged. Indeed, he thought it ‘astonishing, that [the Indian] Government could have listened to such a charge against a good and worthy servant, founded on infamy, fraud and conspiracy’. A third judge thought there was ‘not a scintilla of evidence beyond the opinion of Mr Cooke, founded on hearsay’. Sherson should leave court, he said, ‘freed from all suspicion of having failed in any manner whatever in his duty to his employers’. He was eventually reinstated and in 1815 the East India Company even voted him a present of 20,000 pagodas as recompense for his protracted suspension from office, and sent him back to India ‘with credit’.

The accusation against Sherson has all the hallmarks of a man with a personal grudge using a good opportunity to strike at a rival. The smear of corruption hung over him for a long time before being dispelled (and even after the judges’ ringing endorsement, suspicions about his earlier corrupt activity continued to circulate). On the other hand, Sherson had access to the press to clear his name and he also had powerful backers in the British Parliament. Seven years after he had been suspended, a Member of Parliament, Alexander Novell, waged a sustained campaign to have Sherson’s name cleared. The importance of access to politicians and the press may have been a lesson the family learnt well.

Mark Knights

Mark Knights

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…