Digital Humanities Databases: Help! There’s Too Much information!

Digital Humanities Databases: Help! There’s Too Much information!

Whilst at the DHOxSS those projects that we heard about most frequently involved databases. Databases are of course a significant undertaking and so whilst it is the desire of many scholars to organise their material into a database this is not always a practicable solution. Perhaps the first stage in your (my) database journey is to contribute to somebody else’s project in order to get a feel for what it is like.

One of the projects we heard about at length was the Incunabula Databasefrom Geri Della Rocca de Candal (Medieval and Modern Languages, Univ. Ox.). This incorporates 30,000 eds., in 450,000 copies, from 4000 libraries (more or less). Hence why these projects can be a major undertaking! If you are brave and have a big idea remember that the time and financial costs involve not only those of setting up the database but of maintaining it online.

Furthermore, because of the potential quantity of information that you can be handling, you need to think very carefully about exactly what information you want to include. More might usually be better, but what is practical and what are your priorities? What is most likely to be used and what is already available from other resources? Information which you might wish to include could be:

- Bibliographical (ESTC)

- Typographical (Gesamtkatalog Wiegendrucke)

- Reproductions (Luna)

- Content (Bod-Inc)

- Or Copy Specific (Material Evidence in Incunabula)

Very few catalogues include everything, although many more are now able to be interlinked and source information from each other, thus minimising the need for extra work and facilitating better or more uniform updating. Likewise it is your integration of data from a variety of sources that makes for good research. MEI (Material Evidence in Incunabula) is an especially useful resource since it contains many copies identified from other sources (sales catalogues etc.) that no longer exist, so you won’t find them in the library however long you search.

Why might you use these catalogues, and which catalogue is best for your needs? Although there is no substitute for visiting the library in person (the smell alone is usually worth a train journey), the above catalogues might be used from the comfort of your own desk to research any of the following:

- distribution networks and cost (economic history)

- reception and use (social history)

- reconstruction of dispersed collections (intellectual history)

Which catalogue(s) are best for your needs depends on which of these fields, or any other, you are most interested in.

Remember that even if you never decide to build your own database, or become a card-carrying contributor to a project, you can still do more than simply make use of these catalogues for your own research (for mine, up-to-date and accurate archival catalogues are invaluable). People will always be happy to receive your corrections if you notice an error in the information they provide. They are putting the information up there because they want it to be available in an accurate and accessible form, so don’t be scared to say something.

Another major database project that we heard about at DHOxSS was Early Modern Letters Online, which is a pan-European endeavour, from Howard Hotson (History, Univ. Ox.). This project has a core of permanent staff supplemented by doctoral and postdoctoral interns and the smaller contributions of individual interested academics. I myself may contribute some of the letters of Thomas Johnson to this database. Letters particularly benefit from the database form of recording since the nature of epistolary documents is the disparate location of items belonging to a single exchange. This is something that can be rectified digitally without libraries having to give up their collections. The stated objectives of EMLO are:

- to assemble a network

- to design a networking platform

- to support a network

- studying past intellectual networks.

This database also incorporates the facility of users to comment on documents, facilitating further networking.

A final, smaller, but in some ways more challenging database that we heard about was Ociana from Daniel Burt (Khalli Research Centre, Univ. Ox.). That is, The Online Corpus of Inscriptions of Ancient North Arabia. I would draw your attention to the particular challenges of making this database searchable when the characters of the inscriptions are not currently available on any digital platform. The producers are in the process of creating their own digital keyboard, and of tagging the individual characters of inscriptions, in order to resolve this. The database is also linked to google maps in order to see the geographical position of the inscriptions being viewed, particularly useful since so many are in their original location (ie. on a cliff).

So remember:

- Databases are HARD.

- But that doesn’t mean they’re not useful, and possible!

- I already find such resources essential to my research.

- A good next step for getting to grips with them is to look at contributing to an already existent database, and in doing so learn more about how they work, are managed, and the objectives that are targeted in their creation.

Emil Rybczak (English) Univ. Warwick.

Emil Rybczak

Emil Rybczak

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

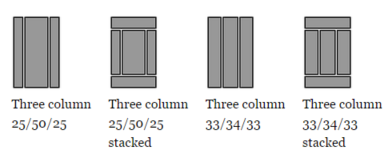

of a grid arrangement. In deciding what template would be appropriate, you would look at the nature of data the page is to display, and an appropriate layout. This works fine with regular pages and datsets, but has become a recurring issue with datasets we've encountered in the digital humanities.

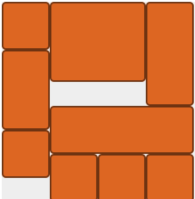

of a grid arrangement. In deciding what template would be appropriate, you would look at the nature of data the page is to display, and an appropriate layout. This works fine with regular pages and datsets, but has become a recurring issue with datasets we've encountered in the digital humanities.  Masonry turned out to be just the javascript plugin needed to help us maximise the use of space dynamically with columns, irregular sized content and responsive design to different device's screen sizes. You can see that this two-column layout maximises the space on the screen, and each block of content takes up as much space as it needs, without impacting the other column. This is the key feature of Masonry, as it removes a fundamental restriction of HTML that prevents such layouts with dynamic content. What it does mean, is that the user is expected to scroll if there is a large dataset to be displayed, but this is not the concern that it used to be with an

Masonry turned out to be just the javascript plugin needed to help us maximise the use of space dynamically with columns, irregular sized content and responsive design to different device's screen sizes. You can see that this two-column layout maximises the space on the screen, and each block of content takes up as much space as it needs, without impacting the other column. This is the key feature of Masonry, as it removes a fundamental restriction of HTML that prevents such layouts with dynamic content. What it does mean, is that the user is expected to scroll if there is a large dataset to be displayed, but this is not the concern that it used to be with an

![if [diigo] then [twitter]](http://blogs.warwick.ac.uk/images/steveranford/2014/07/08/ifttt_recipe.png?maxWidth=593)

Loading…

Loading…