Con Keating

Shortly after it was published in early March by USS, I was asked to review their note “USS briefing: Capital funding and exhaustion risk – distribution of outcomes”. The stated reason for it was: “This briefing note provides details of analysis, requested by members of the Joint Negotiating Committee (JNC), of the risk of the scheme running out of funds before all benefits due to members have been paid.”

The study had however already been in existence for rather a long time as can be understood from this paragraph in the summary of the Valuation Technical Forum (VTF) of November 17th, which states:

“Capital exhaustion

A broad overview was given on this analysis for the forum and what it was looking to consider (i.e., a metric that is looking to test what failure may actually mean as measured by the risk of running out of money to pay benefits). Within the discussion it was agreed that the analysis to date which had been prepared for and discussed with stakeholders be made available on the USS website. It was agreed this would be taken forward.”

It is interesting that there have been three and perhaps four meetings of the VTF since then but no summaries of those have been published. I am not sure if we are missing anything by that non-publication given the summary’s ability to tell us little or nothing of substance, as is illustrated below:

“FMP report to 30 September 2022 (including a discussion on 30 Sept pricing modelling) It was noted that the direction of travel shown in the monitoring continued to be a positive indicator for the 2023 valuation. There was a discussion on self-sufficiency and what other measures could potentially be used to demonstrate the solvency position over time of the scheme. There was brief discussion on inflation which identified the need to understand just how impactful it would be on the valuation outcomes before engaging in a detailed discussion.”

It happens that I have difficulty believing the reported September and December asset portfolio valuations, but this leaves me none the wiser.

Though some of the VTF summary is written in a code unavailable to the uninitiated, such as: “UCU and UUK expressed their desire to have as solid a basis as possible to consider in February, in advance of the 31 March date, and there was a discussion about the art of the possible from the Trustee’s perspective including the sensitivities and book ends that could be provided to the Forum.”, it is clear that the executive’s objective is developing this model was to produce “a metric that is looking to test what failure may actually mean as measured by the risk of running out of money to pay benefits”.

Unfortunately, this modelling approach, which is based on the model developed in their NIESR papers by Miles and Sefton[i], is not fit for that purpose. The software used to produce the published results is produced by Ortec Finance. It is also a total return-based system.

The briefing note is unscientific in that it is not possible to reproduce its results from the information provided in it. This occurs so often in USS publications that one is tempted to wonder if it is deliberate policy. It is though possible to identify, by comparison, some minor anomalies and inconsistencies in the reproduced charts arising from it. One of the more egregious absences is that there is no statement of the statistical properties of the elements of the model, for example the volatilities of the asset classes comprising the portfolio. In a stochastic model, these are crucial.

This is alarming given that “The Trustee is currently considering how, alongside other risk metrics and the wider integrated risk management framework, these outputs might inform future decisions in relation to the valuation investment strategy.”

The central problem is that it deducts the projected pension payments from the stochastically generated asset portfolio as that develops over time, using the returns and volatilities of those asset categories. This can generate some rather strange results as can be illustrated in a very simple model I developed in Excel to illustrate this point. This is available on request.

Mathematically we expect the geometric return of a series of normally distributed returns to be equal to the arithmetic return of that series minus half the variance of those returns. This means that we expect the geometric return, the long run average return, to be similar, at 5.0%, for two series, one distributed N(7%,20%) and one N(5.5%, 10%) but this is not the case. In simulations, we can see the consequence of this, for the N(7,20) case we see ca 650 iterations survive and pay all pensions, the earliest failures occur around year 6 and the average survival time is around 60 years. By contrast, the N(5.5, 10) returns over 800 complete survivals, with the earliest failures occurring around year 16, and the average survival time is extended to around 71 years.

It is clear that in such models, volatility is heavily penalised. This is simply recognition that sale of some fixed amount of an asset is more onerous when that asset is depressed in price than when it is inflated, and the magnitude of those effects is directly related to the range or volatility of the asset value.

This approach to modelling will also deliver exaggerated levels of over-funding, as seen clearly in the USS briefing note charts.

In any event, such an asset only based model, where all pensions are paid by sale of assets is completely unrealistic. Pensions are paid in cash and income in critical in this context. If the dividend and investment income stream is sufficient to pay pensions, exhaustion of capital resources can only come about from the price randomness of the asset portfolio. As this is the most important point in this blog, I shall reiterate it. Crudely put, if the dividend and investment income stream is sufficient to pay pensions, then capital resources are not being touched and won't be exhausted, barring very large numbers of insolvencies, defaults and exceptional situations.

The "if" is important! It is easy to achieve in an open scheme if contributions are added to the income, harder to achieve in a closed scheme.

It should be noted that the variability of income is a fraction of that of market price – a long used heuristic is that equity prices are five times as variable as their dividends. The variability of income from bonds is lower still, indeed bond income may almost be considered deterministic, that is fixed by the terms of the security and the price paid. In addition to this, there is the cash flow from the maturing proceeds of bonds to be considered as this cash flow will also reduce the scheme’s dependence on sales of other assets to pay pensions.

The likelihood of scheme failure is far lower than suggested by these asset-based models. Indeed, they simply bear no resemblance to the observed history of DB schemes, nothing like 17.9% of schemes have exhausted all of their capital resources in the entire UK history of pension schemes. Indeed, I struggled to find any since 1921, let alone the past 60 years.

It is also interesting to note that the lower rates of exhaustion associated with the deficit repair contributions of the model are an implicit recognition of the importance of cash inflows. A 6.1% failure rate falls to 0.0% at 30 years with 10% deficit repair contributions.

Those contributions are described as 10% of the membership payrolls but I do not know how large that is, and the briefing note does not tell us[ii]. My guess would be around £9 billion, given the published higher education statistics. That contribution would represent some 35% - 40% of the pensions payable, around 1.25% in income yield terms.

It is the income aspect of the contributions for new awards which adds to the attractions and efficiency of open rather than closed schemes. Indeed, if the scheme is cash flow positive, that is investment income and new awards are greater than current pensions payable, the scheme will prefer lower prices and their higher potential returns to the high prices preferred by a closed scheme in run-off.

I will end this blog by touching on the question of leverage in schemes. As has been noted elsewhere, this can place significant demands on the liquidity of schemes, that is their cash available to pay pensions and that could have catastrophic effects, a slow-motion car crash.

It is absolutely clear that this USS model is not in any way fit for the purpose stated.

[ii]Since writing this, I have been directed to the 2020 valuation which reports active membership payroll as £8,962 million.

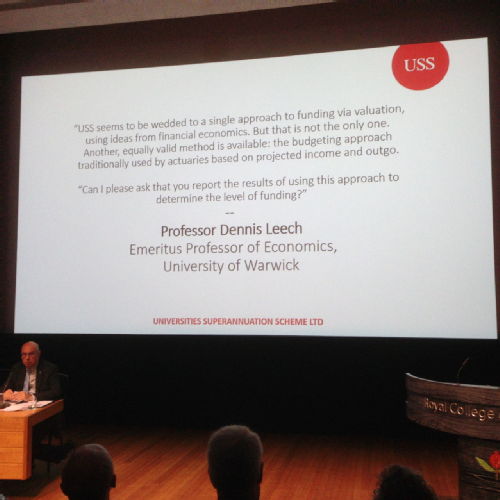

Dennis Leech

Dennis Leech

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…