All 88 entries tagged E-Learning

View all 300 entries tagged E-Learning on Warwick Blogs | View entries tagged E-Learning at Technorati | View all 3 images tagged E-Learning

January 30, 2007

Announcement: Second Arts Faculty E–learning Exhibition Lunch, 9th February

Follow-up to Second Arts Faculty E–learning Exhibition Lunch from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

Second Arts Faculty E-learning Exhibition Lunch, 9th February

The second Arts Faculty e-learning lunch exhibition will be held on Friday 9th February between 12:30 and 14:30 in the Graduate Space, 4th Floor Humanities (having been postponed by a week). As before, the format will be informal, with showcase posters, demonstrations on request, hardware to try out, and experts to advise you. Please feel free to pass this invite on to others, all are welcome (but it will help if you could send an email to artsfaculty@warwick.ac.uk so that we can estimate numbers)

Even in the short time since the last exhibition, many new features and tools have become available (such as Sitebuilder page personalisation, Files.Warwick file-sharing and storage, Sitebuilder term planner calendars). Our impressive set of examples of successful e-learning work has also grown significantly, with several new showcase presentations to view. If you did come to the last exhibition, there are many good reasons to come back for more (including the excellent food).

The theme of this second exhibition is “supporting students at a distance”. We will look at how technology can be used to enhance teaching and learning whenever students are situated remotely (some would argue that students are quite often at a distance). We hope to demonstrate that these techniques are useful in all teaching contexts. If you would like to contribute to this with your own examples, then contact me for details.

The exhibition will deal with this theme by addressing four common problems:

1. keeping students and tutors focussed;

2. keeping people connected (community and communications);

3. developing roles, responsibilities and identities, making them appropriate and well understood;

4. supporting research, creativity and enterprise.

Experts will be available to provide support, including:

- Jenny Delasalle, from the Library Innovations Unit (Build-a-Link deep linking, bibliographies, online book and journal scanning project);

- Richard Parker, head of Library Arts Team (Warwick History of Arts Skills Programme, Refworks, JSTOR, Arts resources);

- a representative of the Elab Sitebuilder team;

- Robert O’Toole, Arts Faculty E-learning Advisor;

- Steven Carpenter, Sciences E-learning Advisor (video and audio expert);

- Chris Coe, Social Studies E-learning Advisor;

- a representative from the Learning Grid;

- representatives from the Centre for Student Development and Enterprise (skills Recipe Cards, Warwick Skills Programme, Graduate School, ePortfolios).

Other items at the exhibition will include:

- details of new features in Sitebuilder and Warwick Blogs;

- a map of e-learning activities in the Arts Faculty;

- leaflets from Elab, IT Services, CSDE, the Library etc;

- a suggestions board, to feedback to Elab and the Library;

- an opportunity to arrange training sessions for your department.

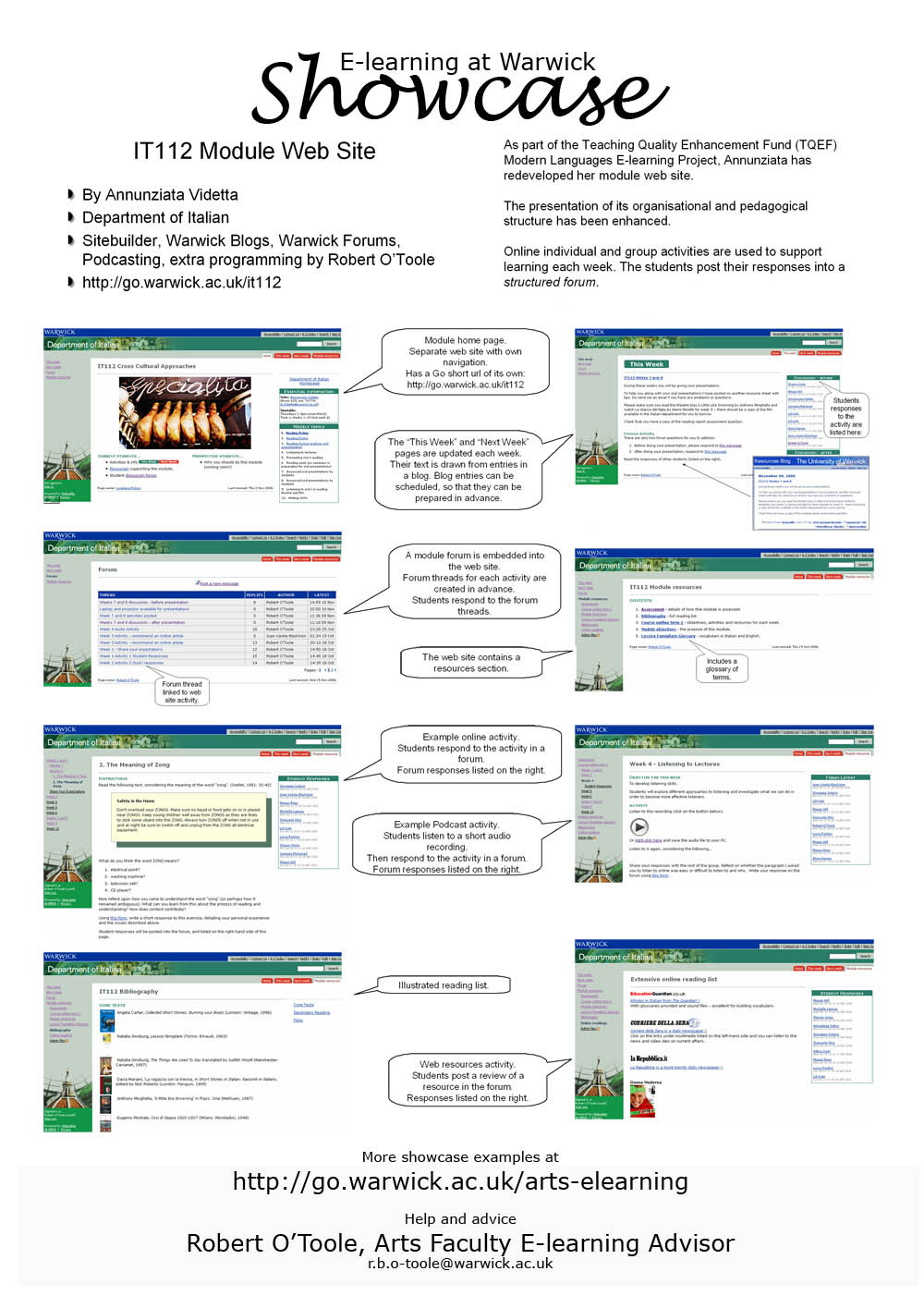

Showcase poster design for e–learning exhibitions

Each poster demonstrates an example of the effective use of technology in teaching, learning and research. It has four elements:

- A series of statements about what it demonstates, who did the work, what technologies and techniques it employed, along with a url to the showcased work.

- A few short paragraphs of text (100 words maximum) explaining the rationale behind the showcase.

- A series of annotated screenshots or photographs demonstrating and explaining what has been done (a maximum of 8 on an A2 poster).

- A footer containing a link to the Arts E-learning web site and details of the E-learning Advisor.

The posters are printed to A2 (we have a colour A2 printer). My method for producing them is slightly odd. I first create each text element or image within a Powerpoint presentation, and then copy them into a Photoshop file (set to A2 size). I end up with a poster and a Powerpoint show for each showcase.

Here’s a good example:

If that’s too blurry on your screen, have a look at this it112_poster_small.pdf

For the next series of posters I am going to try to include more information about the processes and support infrastructure used to meet the stated objectives of each showcase.

January 26, 2007

4 essential goals in learning design

Follow-up to Second Arts Faculty E–learning Exhibition Lunch from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

Four problems (or challenges) are obvious. As Sarah Richardson of the History Online MA argues, these are in fact the same challenges that must be addressed by learning design in all higher education contexts (on site and distance). The challenges are:

- keeping students and the tutors focussed;

- keeping people connected (community) – communications and relations between tutors, tutors and students, students and their peers, as well as connections between the students and their departmental, faculty, subject and university communities;

- developing roles, responsibilities and identities, making them appropriate and well understood;

- supporting research, creativity and enterprise (for a definition of what I mean by this, see this article on research based learning).

With these challenges as the basis of the exhibition, my next task is to find showcase examples that demonstrate how our learning technologies support students and tutors in meeting these challenges. For example, I will show how a Sitebuilder term view calendar can be used to help define and keep course members effectively focussed.

January 23, 2007

Second Arts Faculty E–learning Exhibition Lunch

This second exhibition in the series will showcase a wide range of successful applications of technology in teaching, along with demonstrations of new hardware and software. Special exhibits will focus in particular upon the topic of:

Supporting students at a distance (more information below).

The exhibition is open to all staff and teaching postgraduate students within the Arts, as well as anyone else from across the University with an interest or expertise in this topic. It is an informal session, so please drop by at any time during the exhibition. A buffet lunch and drinks will be provided.

Supporting students at a distance

Students at Warwick are frequently expected to undertake work in a location away from the University campus and in less frequent contact with teaching staff and peers. This is not only true of fully distance based courses, but also of the research oriented student undertaking a project out in the field or writing a thesis. Some common examples are:

- full distance learning courses;

- hybrid distance and on-site courses;

- transnational courses;

- year abroad students;

- placement students;

- students in low-contact phases of a course (e.g. writing-up).

Many problems are posed by these arrangements, both to the student and to the tutor, but also to the administrator. Difficulties commonly occur in areas such as:

- establishing and relating to a peer group;

- connecting with the department and faculty community;

- connecting with the wider academic community;

- access to resources;

- understanding (and confirming) module or activity purpose;

- individual study guidance;

- discussing work;

- presenting work;

- submitting work.

Of course these problems may occur in any mode of study, including on-site high-contact courses. The techniques and technologies that have evolved to address these problems are therefore useful in many situations.

Warwick has developed a range of sophisticated but easy to use technologies that allow us to effectively address these problems. The E-learning Exhibition will demonstrate these technologies and techniques, with showcase examples of real solutions by people at Warwick.

We will show how tools including Sitebuilder, Warwick Forums, Warwick Blogs and Perception can be applied to create a learning environment customised to your particular mode of teaching and course delivery, whether at a distance or in close proximity.

January 17, 2007

3 problems of community that technology might address

There are of course more than three problems, that being the story of human conflict and struggle. Sometimes communities cannot form effectively because of disruptions and lack of continuity. And other times individuals within a community may fail to value others or the channels that connect them. Technology can do little in the short term to ease or avoid these difficulties. In considering learning communities, there are however three recurring problems that have been succesfully addressed with technology.

1. Problems of size and complexity

In some cases the student is overwhelmed by the size and complexity of the institution. They need to break it down into smaller and more manageable segments, so as to be able to judge the value and usefulness of its features, and to form stable and repeatable connections. But all they see is a crowd. There is some truth in the claim that the best communities are in fact composed of small groups of people, perhaps as few as eight, with each group well connected to other groups. This supports adaption and diversity, whereas mass communications and transactions negate diversity and prevent adaption. It certainly is the case that people struggle with meaningful activity within big groups.

2. Beyond the clique

In other cases, the student has a strong, even dominant, small network of friends, peers and tutors. This network provides for some but not all of the individuals needs. Connections to other groups are mediated by the group, and thus may be severely restricted. They therefore need to go beyond the clique to find new connections, new resources. But how? It’s a big and scarey world out there. This problem can be particularly acute for distance learning or part time students, who have little time or opportunity to go out exploring on their own.

3. Loss and dispersal

Many students at Warwick are expected to undergo phase transitions that break them away from their established networks. They commonly experience a loss of community. This is common in the Arts Faculty, with many students spending their second year abroad.

January 05, 2007

What features are useful in a module web site?

Here is a map of the features that we have selected as useful…

There is a Captivate presentation about the site online. You can also view the module web site ( now updated for this term ).

The site has moved away from being an online replication of the module handbook. It’s primary functions are now:

- Keeping the students focussed, up to date and guided in their work.

- Hosting discursive responses to pre-seminar and post-seminar questions posed by the tutor.

- Distributing links, bibliography and files.

- Hosting interactive online activities.

The home page (1) retains a list of module topics (1.2) alongside essential information (1.3). These are presented in an efficient at a glance structure. A series of images is used to give a sense of the identity of the module. Links (1.4) are provided to the other key aspects of the site. This term I hope to add some code that will highlight the current topic in the list of topics.

Complimenting the ‘at a glance’ overview, this week (2.1) and next week (2.2) pages efficiently convey the most essential and relevant information to the students in a timely manner. The content of these pages is updated throughout the term. Importantly, old content from these pages must be archived (2.3). The weekly content is in fact stored in a blog. The latest entry in the blog (tagged appropriately) is shown via RSS and an XSL conversion on the ‘next week’ page, using some custom code that I wrote for the job. Such feeds are now standard in Sitebuilder 2, so I will soon switch to the standard supported feature. The ‘this week’ page gets its content from the second newest blog entry. Blog entries can be written in advance and scheduled to appear at a certain date and time. This will allow us to write the weekly entries in advance.

Each week the students are provided with important information, links to resources, and links to online activities (we have in this case written some interactive exercises). There is a resources section of the site in which these are organised. One activity last term involved the use of a podcast recorded with one of our MP3 recorders. There will be more podcasts used this term.

The most succesful and common of the weekly activities are forums based. The student is given an activity to do or some thing to consider. They are then aksed to respond to a pre-entered forum message (4.1). The students responses each week build up as a thread responding to the message. In each case I link directly to the Forums reply form for the message. This is setup to redirect the student back to the ‘this week’ page.

The responses are listed on the right hand side of the page (2.1.3.1.3). To do this I again use RSS and cusotm XSL to dynamically display the latest messages. The forum is also embedded in the web site as a single page on its own, allowing students to review past discussions (4). We have also allowed students to start their own threads in the forum on any topic connected to the module (4.2). Students receive notification of new postings automatically through Warwick Forums.

January 04, 2007

Using digital media: copyright, DRM and safe [e]learning practice

Key sources on which this is based:

- Copyright Made Easier. Wall, Raymond A. ASLIB, London, 2000.

- Intellectual Property and Copyright in the Digital Environment CARET. University of Cambridge (excellent web site).

- British Universities Film and Video Council course on copyright

The bad news

Contrary to popular belief, there is no blanket ‘fair use for education’ exemption within British copyright law. Furthermore, educational bodies are increasingly considered to be commercial organisations. If we infringe upon the rights of another commercial organisation, they are likely to pursue us for compensation. The position of the university on this, as embodied in its acceptable use policy (AUP) for IT, is that individual members must not use University facilities to commit such infringments. Employees of the University should not commit such infringements in the course of their work.

Although we have a limited license agreement that allows us to reproduce certain copyrighted materials on paper, there is as yet no such agreement covering digital media. Similarly, print media that has been digitised is not covered. The Library are currently piloting a very restrictive digitisation license, but only in a controlled way. There is a good reason for this limitation, from the perspective of copyright holders. Once content has been digitised, it can be redistributed to thousands or even millions of people at the click of a mouse button. When this happens, they no longer have control. Digital rights management (DRM) systems are being developed to allow controlled digitisation and redistribution, but are not yet widely used.

The situation becomes worse when digitised material is uploaded to the web. Redistribution then becomes even more simple. It is often assumed that storing content on a password or permissions protected web page is acceptable. Rights owners would counter that the material may still accidentally or deliberately be ‘leaked’ into a public realm by anyone with access to the restricted page. Imagine if a student were to make a copy and then post it publicly on their blog. Auditing of digitally stored materials may occur, even behind protected pages, and this can lead to painful consequence.

The good news

There are three significant exemptions that we can exploit. Firstly, and most well known, are the various expiration periods of rights under protection. For example:

- In literary, dramatic, musical or artistic works copyright lasts 70 years from the end of the calendar year in which the author dies.

- Sound recordings, usually 50 years from the end of the calendar year in which the recording is made (there are complications).

- Films, 70 years from the end of the calendar year of the death of the last to die of the following persons: the principal director; the author of the screenplay; the author of the dialogue; and the composer of music specifically created and used in the film.

(Adapted from the Cambridge University copyright web site )

However, you might want to use more recent materials. There are two further ‘permitted uses’ available to us:

- Making copy for personal research or private study – and that means personal, you cannot use this exemption to make copies for groups of students or researchers. They can of course make their own copies.

- Reproducing an ‘insubstantial part’ of a performance or publication for the purposes of criticism or review.

One could argue that much of what we do in higher education, especially the arts, constitutes criticism or review. This enables us to use citations from publications or small lower quality images of artworks without explicit permission (although it is often good practice to ask first, as this keeps artists and publishers sweet). There is a significant caveat: ‘insubstantial part’. This does not necessarily describe a quantity of the original work. To calculate whether you are reproducing a ‘substantial part’ consider this question:

Would the acquisition (or viewing) of my reproduction make the acquisition (or viewing) of the original in some way unnecessary?

If yes, then you have definitely used a substantial part. For example, this is the clause that prevents theatre critics from giving away the ending of a play. Note that you can still use your criticism to convince people that the play isn’t worth seeing on artistic grounds. For more information and ideas on the permitted use for criticism and review, read this blog entry.

And finally, remember that if you really must use a substantial part (or whole) of a performace or publication, it is worthwhile simply asking for permission from the copyright owner. Explain to them how you are to use it in education or research, tell them that it will increase the prestige and even sales of their work, and reassure them about how you plan to control access to the reproduction. There are organisations that exist to support this process. I will investigate these and report further.

Technology for research based [e]learning – presentation abstract

Advances in entrepreneurial and research based [e]learning at Warwick

Warwick has developed extensive [e]learning provisions: web architecture, software and hardware catalogue, support and training, network of experts and advisors, research and development programme, and most importantly a culture of innovation (especially amongst students). This has been undertaken to serve the needs of an entrepreneurial and research oriented university.

Our focus is then upon using technology to enhance student academic processes, key research and enterprise skills, and their assessment. This is achieved by making the tools and techniques used by researchers and entrepreneurs available to students. At the same time, we extend the technical capabilities of our academic staff as researchers. We aim to foster a digitally native, collaborative, network oriented, technically proficient and media savvy university population, staff and students included, such that research and enterprise is enhanced throughout. This represents an entrepreneurial and research oriented agenda for e-learning.

I will begin with a concise but effective clarification of the concept of entrepreneurial research based [e]learning, thus providing a framework through which specific technologies can be understood:

- Valuing the process as much as the product (and implications for skills and assessment).

- Students as researchers creating and developing novel opportunities (four essential research skills, the link between research, creativity and enterprise).

- Surveying and understanding current knowledge (revealing gaps and contradictions in knowledge, making opportunities appear, questioning and investigating).

- Beyond content transmission (digital nativity, collaboration, critical reflection, network/community orientation, technical proficiency and media savviness).

I will then provide a brief overview of the technologies and techniques that we have made available, evaluating how each of these supports entrepreneurial research based [e]learning differently.

Two particular technologies/techniques will be subjected to thorough investigation: podcasting and concept mapping. These have emerged, largely without conscious planning, as popular and effective tools. Podcasting, as a student collaborative research activity, has shown great promise. It has also proved popular with older staff, who find its radio-like format to be familiar and useful. Concept mapping (as opposed to mind mapping), has been rapidly adopted by individuals and groups as a tool for gathering and analysing information. It is a highly effective tool, and yet simple and intuitive to use even when dealing with large and complex domains. I will demonstrate how it can revolutionise learning, research and collaboration through the application of critical and analytical processes.

December 13, 2006

What is concept mapping? – and how could it be vital to your work?

Many of the things that we (in business or academia) work upon require efficient access to tens, hundreds, thousands or more related items of information. Each item of information may be small but at the same time distinct and important in itself. Think of an example from a domain that you work on. It could be a daily process like working out your schedule, or perhaps something more exotic, like designing a new rocket ship. The items of information involved might be many simple and diverse attributes of a real world entity, or perhaps events within an abstract and difficult process of reflection. Complexity is everywhere, and we need to manage it.

Complex domains of information can sometimes be stored within a database. These are usually designed according to tried and tested methods, using sometimes esoteric logical structures. However, in many cases, there is neither the need nor the opportunity to build such a formal solution. Database design is an expensive, specialised and time consuming business. When it goes wrong, the consequences can be painful for the end user. Perhaps a formal structured database is the wrong kind of solution anyway. In many cases, there is no obvious or simple structure to our information. Perhaps a structure could emerge over time, given enough data and sufficient opportunities for its analysis. But how then do we store and use large amounts of data, to enable structure to emerge, without a structured database design? The chicken-egg precedence issues are obvious.

What if it were possible to store large numbers of small items of information in an ad hoc way, with only a minimal schema or even none at all? Perhaps some degree of structure could then emerge during the process of storing and reflecting upon it. This could be a middle way between a structured database and a simple list. Concept mapping has developed to fit precisely this niche.

Concept maps have, for a long time, been scrawled onto paper and whiteboards in the hope that they will help to make more sense of what we know and what we don’t know. People find the approach to be effective for a wide range of uses, including:

- recording research information;

- recording known information and identifying gaps;

- fast generation, analysis and ordering of ideas;

- identifying patterns, relationships, causality, priorities and hierarchies;

- recording tasks and resources;

- planning projects;

- communication of ideas using the map itself;

- generating presentations and documents from the map;

- frameworking writing;

- assisting memory;

- cooperative thinking;

- decision making;

- designing system schemas;

- keeping a journal of individual or team activities.

Now take this simple idea, and add to it a brilliantly intuitive interface for storing and organising information within ad hoc structures. Combine this with powerful tools for extending that information (with text, links and metadata), and for searching, filtering and outputting the results. Would that be of use? If so, MindManager 6 from Mindjet is the application for you. It is the most professional, sophisticated and easy to use concept mapping system. Warwick has a site licence (Windows, on campus only) and a rapidly growing population of users.

Read on for more about concept mapping and MindManager.

What is a concept map?

A concept map consists of:

- A central topic defining the domain (problem, or object) that the map is about.

- Many small items of information about that central topic, the sub-topics of the central topic, such as facts about events and entities (real or imaginary).

- Connections between topics.

- Hierarchies, such that some topics are sub-topics of other sub-topics. Information is ordered into a tree structure with multiple branches and leaves.

Here is a simple example. It is a concept map about me. There is a central topic (in this case with an image). This has four sub-topics. Two of these sub-topics have their second level visible. There is much more information on the map, but it is hidden from view within closed topics (the + sign next to a topic indicates that it contains more). Note also the hyperlinks to web pages.

Concept mapping is the process of building such structures. The purpose is twofold:

- To help to generate and to handle unstructured information;

- Where necessary and appropriate, to draw out order and organisation.

For this to be possible, it is essential that our concept mapping techniques and tools allow the following:

- The easy addition of topics regardless of patterns and structures.

- A simple mechanism for moving topics from one branch of the tree to another.

- Clear and simple means of presenting and reviewing the structure and the information that it contains.

- The ability to search through the text of all of the topics on the map.

MindManager has all of these facets. New topics are entered simply by pressing the Enter key and typing. Sub-topics are entered with the Insert key. Topics are moved using drag-and-drop mouse controls. The on-screen and print view of a map can be manipulated to hide or show detail, and to scroll and zoom as required. A text search tool zooms into matching topics (and searches topic notes). It is, in fact, so simple that a new user can generate a complex but useful map in minutes.

Beyond simple concept mapping

So far this should sound pleasingly simple if not blindingly obvious. However, if you have used such techniques in any depth, you will already know that they have their limits. Want more? MindManager introduces some additional aspects to concept mapping, implemented with more sophisticated but easy to use features:

- Any topic may also contain images and a more detailed text (hidden until required).

- Both topics and the links between them may contain ‘call-out bubbles’ with additional short comments.

- Topics and links can be formatted either for presentational or informational purposes.

- Topics can be linked to documents and web pages outside of the map.

- Topics can be linked to other sub-topics that are not contained on the same branch of the tree.

- Additional meta data can be attached to a topic, allowing it to be categorised and described in further structured ways.

Breaking out from the tree

Features 4, 5, and 6 listed above help to transform the rigidly arborescent tree structure of the map into a more complex web like or rhizomatic structure. Trees are fine for many things, but as our ancestors discovered, you can only do so much by clambering up and down the branches.

There are very good reasons why you would want to go beyond arborescence. Most obviously, the real world, with its objects and events, is not structured like a tree. For example, Rachel may be the son of David, and could be represented as a sub-topic of David. However, Rachel is more closely allied to the Socialist Workers Party, a fact that we should never forget when considering her. So should she also be a sub-topic of the SSWP topic? A simple tree structure would find that difficult.

Perhaps we could link her topic node to the SSWP topic? There’s another much more powerful option: text markers.

Text markers

A text marker is a kind of keyword tag. For example, we could tag Rachel’s topic with the text marker “SWP member”. Other people on our concept map could also be tagged with this text marker (but not David, her father is a devout Tory). This could be an aid to finding all of the SWP members within our research data. Or, more interestingly, we could use it to search for patterns in the data. Perhaps we would see that the SWP are systematically infiltrating certain types of other organisation, in preparation for a coup d’etat. MindManager allows us to create whatever text markers are required whenever we want. It does, however, encourage some organisation within our text marker schema. Markers should be organised into groups, so for example we would have a text marker group called “SWP”, containing the markers “SWP member” and “SWP activist”.

Filtering

This is a feature that always prompts a “wow” when it is demonstrated. Once text markers have been applied to the topics on a map, a filter can be constructed to show only topics with specified text markers. For example, if we wanted to find out who the SWP activists are, we would select the text marker “SWP activist” and apply a filter. This can be used for analytical purposes, or to simple make the map easier to use.

Icons

For a more visual alternative to text markers, a set of meaningful icons can be applied to topics. For example, there is a set of emoticon icons including various smileys.

Topics as tasks (project management)

In MindManager each topic may also be treated as a task, with a start and end data, priority rating, progress percentage, and resources. Filters can be applied to the map, based upon these attributes. There is then an easy route between a concept map and a managed project.

Conclusion

Many people will have heard of concept mapping. Most of them assume it to be just another productivity or creativity technique. I argue that it is much more significant. Based upon the survey given above, I put concept mapping and its software applications into the same taxonomic class as wordprocessing, relational databases, email, and the web. It is that fundamental. Imagine life without those other fundamental applications? That should give you an idea of the scope of what you are missing out on.

Training

As part of my E-learning Advisor role, I can organise training sessions for groups of between 4 and 12 people. I only have a few free slots each term. Arts Faculty staff and teaching postgrads have priority, but others can be accomodated. Please contact me to enquire.

August 29, 2006

Random opinions about blogs and bloggers

We did try to get a mix of bloggers and non–bloggers, however, there seemed to be few bloggers around (perhaps they were all locked away in dark rooms desperately trying to write something worthwhile).

Note that it was compiled from victims found in University House during the summer vacation. The undergraduate population, at whom the blogs publicity campaign had been targeted, was scarce.

It reminds me of Aardman's Creature Comforts. Perhaps we could substitute animals for some of the familiar faces that appear. Any suggestions?

July 19, 2006

The problem of transferable learning technology development – some guiding rules

There is an approach to the development of software known as 'agile' development. Based upon years of painful experience, it priveliges the frequent delivery of quality new features, with constant review and improvement (where strictly necessary), over the master–plans and monoliths that are forever looming up on distant horizons. It is a sensible approach that should perhaps be applied to domains beyond IT. Another of its principles is that rather than trying to satisfy a large number of poorly engaged and un–committed users, it is better to work closely with a small number of closely involved and enthusiastic individuals. This again is a sensible option. Developments thrive on quality feedback, direct from the field, delivered first hand and with the necessary degree of detail.

There is, however, a potential trap in this approach. What if those committed enthusiasts turn out to be mere eccentrics? What if they are unrepresentative of the majority? Perhaps the majority over time will follow their lead? In which case they stop being eccentrics and start becoming early–adopters. Or alternatively, other people may never adopt the new development. In some cases, the correct course of action is to simply seek other enthusiasts, other more promising directions. When one is adding new features/possibilities to an already existing service/pattern–of–behaviours, such change of track is acceptable occasionally. But there is a cost in terms of waisted opportunity, resource, and in people's tolerance of the process. Choosing enthusiasts well is therefore important. When one is initiating entirely new services/patterns–of–behaviours, the problem of who to trust is even more critical. For example, Warwick Blogs was built upon the asumption that a relatively small number of people had a representative and reasonable view claiming that many other people would adopt it once it became available. The innovation seems right to these people. Added to that is some justified belief that it will also transfer beyond that minority, and that this transferability will justify the effort undertaken to get the new service to the point at which a wider range of people can become enthusiasts engaged directly in the development process.

Are then such assumptions of transferability safe? Perhaps sometimes. In some cases the target user population is distributed amongst a very simple ecology – that is to say, there are few differing niches, and similarly few adaptive responses to those niches. Everyone behaves in the same way. Everyone wants the same things. I suggest that the ecology of learning, teaching and research at Warwick is not such a simple ecology. There are in fact multivarious niches, each with a range of overlapping adaptive responses. People here are varied and unique. In fact, as I have argued elsewhere, higher education in Britain is full of such variation. Diversity is encouraged. The result being the demise of the monolithic VLE and the rise of the individually selected mesh of diverse features. Ask a Warwick lecturer in English to describe their ideal learning technology environment and the answer will be different to that of an Oxford lecturer in English, and no doubt different to another Warwick lecturer in English.

The practical result of such diversity is that when given a limited resource and the need to engage and satisfy a large number of people, choosing what services/patterns–of–bahaviour to focus upon is difficult. How is transferability achieved? How do we judge whether we are satisfying an isolated niche or feeding the whole ecology? Difficult, but perhaps there are some guiding rules.

Rule 1

If a smaller number of unrelated users from quite different niches all respond positively to a proposal, or better still come up with the same proposal themselves, then this most likely points to some aspect of the proposal that is transferable across the niches, that has utility and attraction in every case.

This is always more indicative of transferability than when a larger number of users from the same niche back a proposal.

Rule 2

If you want adoption of the proposal to spread more widely than these few diverse people, then a second rule is necessary.

It is quite possible, in an ecology like Warwick, for people to occupy similar or tightly–knit niches, but in significantly different ways. Take two lecturers in philosophy, look at how they prepare lectures, and it's likely that you will see some dramatic differences. Therefore the second rule is: identify the current behaviour of each of the interested users to see just how the proposal fits in, consider how common this is to other people in their vicinity, and ask whether that will make a difference to its adoption within their niche. Just how typical is the relevant behaviour of philosophy Lecturer A in comparison to other philosophy lecturers? Looking at this from another perspective: is there anything that blocks other philosophy lecturers from adopting the proposal that has been adopted by Lecturer A?

Rule 3

In some cases, rule 2 would seem to indicate that transferability is unlikely. Philosophy Lecturer A cannot transfer their new found technique to people in their immediate vicinity. It may however still be worthwhile to other people. In such cases we should seek or create lines of transferability that link up isolated people in separate localities, perhaps with other things in common. For example, the PhD student ePortfolios brings together individuals with isolated needs from many locations.

I am certain that there are other useful guidelines. Feedback would be most welcome.

_

1. services are always coupled with behaviour patterns, never think of them simply as assemblages of features, as those features are only meaningful when used.

July 18, 2006

Do digital natives have differently wired brains?

Writing about web page /johndale/entry/digital_natives/

Writing about an entry you don't have permission to view

What is the relationship between interior design and learning technology?

At the moment there are two big concerns that are occupying my thinking. The most pressing of these is the need to reorganize our large three–story four bedroom house so that the generously portioned spaces within it start to support the kinds of activities and lifestyle that we want. My biggest demand of a home is that it be a place in which I can write. It must contain a writing studio, with all of the elements that make up such a place. Not being an [entirely] selfish person, I also want it to accomodate the extremely adventurous spirit of a one year old baby (one day he will climb Everest), and an overworked KS1 co–ordinating teacher/wife. The second of my big concerns is the question: how do we make a digitally native university? – and the implied question: what does it mean to be digitally native? There is a genuine and interesting connection between these problems.

The interior design problem forces me to reflect on how I get things done. What is my learning/doing/creating/writing style? I do certainly lean towards the connector end of the academic connector/dissector continuum. My process is as follows:

- Rambling, mooching, bimbling and fiddling;

- With occasional frenetic and concentrated bursts of activity, gluing things back together and boiling them down.

If you were to watch me work, you would see much more of the type 1 behaviours. You would also be surprised by the amount of space that it takes up. My ideal writing environment contains lots of different materials (books, papers, photos, artworks, maps, etc), all open and spread out for long periods of time. I'm not an indexer. I don't have a system. I'm a haptic/tactile kind of thinker. I make a big mess of fragments, each of which may have post–it notes or scraps of paper attached. Plus there are cups of coffee and items of food. However it certainly isn't total chaos. I always have a mental map of what has been discovered and laid out. And I don't want that map to be disturbed, because it is the thinking process. My thinking process is what cognitive scientist Andy Clark calls extended cognition

And furthermore, this is never a stationary process. I wander around. I sit in odd positions. I look out of the window. I walk in the garden and beyond. Until suddenly a tipping–point is reached and I sit down and write. And after that? More wanderings, with occasional trips back to the computer to edit the text with some correction or new insight.

That then describes how I work. It is, I believe, how many other people work, both now and in the past. Although few people have taken this art to the extremes of Francis Bacon's studio. There is, however, gathering support for the notion that 'young people today' are cognitively different, that they think in a different way. Marc Prensky has invented a pair of terms that encapsulate this difference: digital natives and digital immigrants. The proposition is this: people who grow up in an environment built from online and digital technologies have thought patterns that are significantly different to the previous generation. It is claimed that they are less concentrated, that they multitask most of the time, that they process a wider range of sources, that they tag (categorise with keywords) or discard more readily. There is then a claimed generational difference, one that must be at least challenged by my interior design requirement, for I have realised that there is actually little difference between the so-called digital native approach and my old-fashioned paper-centric approach. There is definitely a difference, but first we should dispel the conjecture that there is a fundamental cognitive difference. Andy Clark has demonstrated that there are many such forms of 'extended cognitive apparatus' some of which work in this way and which have done so for many years. Digital online technologies are just the latest addition. There is no revolution in the structure of our brains.

There is, however, still an obvious difference. The apparatus of extended cognition have been extended significantly. The physical/haptic space merges into a digital space of unlimited depth. The question of whether this new digital space can ever overtake the non–digital is significant in itself. I would argue that software still cannot replace my writing studio. Except in one very significant way. Few people will ever visit my physical space, but tools like Warwick Blogs allow it to be extended into a potentially huge social network, with much greater possibility for collaboration in the thinking process. I argue then that this is the real aspect that marks out the digital native: a greater ability to collaborate and to manage collaboration using digital and online technologies.

July 04, 2006

Blogs in Learning Research Symposium – agenda first draft

A more final, but still draft agenda can be seen in the e-learning web site.

Feedback?

If you are already an invited participant, then please feel free to comment on whether this fits your interests, and if there is anything missing.

If you want to come to all or part of the session, then please contact me, we might have some spaces left.

June 30, 2006

Thematic Navigation and Contextual Navigation

Firstly, some definitions:

Of course such convoluted routes are usually circumvented through the use of bookmarks. The user jumps right into the required context, or at least one close enough to it so as to save time. In such cases other tricks are required to speed up the communication of context. In the Sitebuilder web content management system, each sub site (department, research project, sometimes course and sometimes even individual modules) have their own visual design (within the boundaries allowed by Sitebuilder). This design provides instant visual contextualisation. Warwick Blogs, however, is much more flat in terms of context. Each individual blog has its selected design (sometimes customised) and title. All entries are presented in that context. Even pages that represent entries with a single tag vary little in contextualisation. So for example, my Philosophy Research page looks just like my Baby Lawrence O-Toole page.

Thematic navigation may therefore connect content across contexts. This has obvious advantages, in that related content is automatically aggregated together. But more interestingly for learning and teaching, it encourages the end user to view related content from different contexts, and consider the differences between those contexts explicitly. So for example, a topic may appear in the module of a lecturer in Continental Philosophy, and in a module by a lecturer in Analytic Philosophy.

An obvious question to raise at this point is this: surely this could be achieved by the student doing a free–text search of all of the pages (or even the whole web)? Yes, but, if each of the lecturers were to consciously assign themes to their pages from a pre–figured set of themes (possibly even a taxonomical model), and the student were provided with that model as a guide to understanding the course, then they are given clearly specified and consistent concepts for understanding a diverse set of content or activities. This happens to be an important and widely respected pedagogical method. Curricula are in fact often designed as a combination of contextual navigation (modules, lectures, seminars, assessments) and thematics that run across those contexts (skills, concepts, competencies, objectives, values etc). Almost all of the modules that I am asked to look at work in this way. A diverse series of activities is undertaken, which have their own developmental logic. But alongside that diversity, a core set of concepts (often skills) are supposed to be the objective focus of development. However, frequently the problem is that the students and lecturers do not understand the themes, or lose sight of them in the diversity.

Web publishing channels of communication

Follow-up to How to write a communications strategy from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

My table maps each of the following channels/technologies:

Static web site (Sitebuilder)

- Department

- Module

- ePortfolio

Blog, web log, online journal (Warwick Blogs)

- Individual

- Team

Discussion forum (Warwick Forums)

- Public

- University wide

- Restricted group

Interview or recording

- Podcast (MP3 recorder, Sitebuilder)

- Online video (Video camera, Sitebuilder)

Against these parameters:

- Owners (in order) – in each case what type of person[s] has ownership of the channel? For example, an individual blog is owned by a single person;

- Broad or narrow cast?– is content aimed at an unspecified wide audience (broadcast) or a known/delimited audience (narrowcast);

- Audiences – who is it typically used for;

- Update pattern – summative or accumulative? Accumulative channels add new content to old (blog), rather than replacing it.

- Visual design – how does the look get determined? How much control do the owners have?

You can download the file from the E-learning at Warwick web site Please feel free to redistribute it as needed.

Robert O'Toole

Robert O'Toole

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading