All entries for October 2018

October 29, 2018

Running ABC workshops – Abigail Ball

In March 2018 I attended a JISC workshop on data-informed blended learning design and was introduced to the ABC Model of Curriculum Development by Natasa Perovic and Clive Young from UCL. The event was timely for me as I was wrestling with how to effect transformative change on established face-to-face programmes with respect to Technology Enhanced Learning (TEL) as opposed to reactive and incremental change which seemed the increasing norm.

The workshop demonstrated how a facilitator could encourage participants to evaluate their current teaching practice and through making relatively simple changes, develop a more blended approach supported by the appropriate use of technology. I was conscious that I did not want to tell staff that they needed to make changes; instead I wanted the recognition of the need for change to come from them; for them to take ownership of the change process.

In June 2018 I was asked to run a curriculum development session on a planning day for the team developing our online PGCE International programme (PGCEi). The original plan was for me to have a 90 minute slot (the same length of time as the original JISC ABC workshop) and to facilitate participants through the process of identifying how the current PGCE was delivered and what they might want to reuse, repurpose or develop afresh for the new PGCEi.

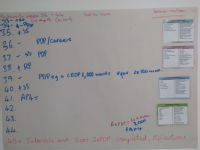

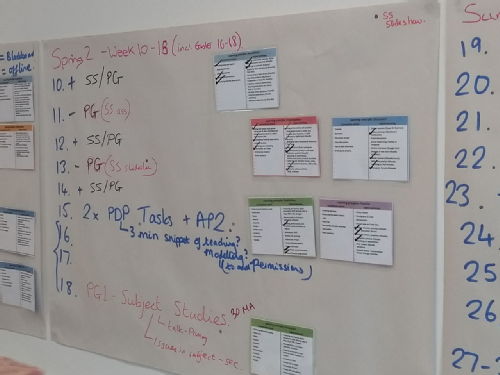

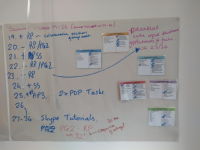

What quickly became apparent was that the original time slot was simply too short; we ended up working on this for four hours. We developed a comprehensive timeline for the programme (see Figure one below) which helped to frame our discussions. We then went through the teaching activities the team had provisionally identified and mapped them onto the different learning types using Laurillard’s Conversational Framework. This showed clear clusters of learning type (e.g. acquisition) which enabled staff to discuss how they might adapt their teaching activities to use some of the less well-used learning types (e.g. investigation).

Figure one

At no point did I suggest that an over-reliance on one particular learning type was poor academic practice or that staff should reduce the amount of acquisition they used with the students. The staff came to this conclusion themselves. The visual nature of the storyboard activity worked really well and made it easy for staff to see the impact of their changes. Each of the learning activities was explicitly related to the assessment points to ensure relevance for the students. When these were spread over the length of the programme it became clear where potential stress points might be and how we could mitigate them by adjusting the learning type (where appropriate) or by reducing the learning activities generally to gain more of an even flow across the programme.

We have subsequently met to discuss specific learning activities in more detail and each time the timelines have been used to frame the discussion. Lessons learned from the workshops include:

- Allow plenty of time for the programme (90 minutes is not really long enough; I would allocate at least half a day)

- Use an appropriate room which gives plenty of space for spreading out and sticking things up on the walls (for a process looking at TEL it is remarkably practical and low-tech!)

- Provide refreshments as this helps the flow of discussion

- Use the ABC icebreaker activities (e.g. creating the Twitter summary); they get staff into the right frame of mind for considering the programme as a whole before getting into the nitty-gritty of the learning activities

October 22, 2018

The ABC of International Curriculum Design – Nick McKie

As part of the curriculum development planning for the Warwick PGCE international course we attended an engaging hands-on session led by lead academic technologist, Abigail Ball.

The main premise of this session was to enable us to identify the key principals of course delivery before we drilled down further into module content planning. The session was structured around the Arena Blended Connected (ABC) curriculum development model which we used as prism through which to craft reflections on our own curriculum development.

The ABC model

Created by UCL Digital Education, the ABC model is a collaborative workshop where a visual story board is produced to sequence learning activities, assessment and outcomes. Through this model we looked at the following different learning types:

- Acquisition: listening to a lecture, reading from books and watching demos.

- Collaboration: discussion, practice and production.

- Discussion: articulate ideas and questions.

- Investigation: explore, compare and critique.

- Practice: adapt actions to the task and use feedback for improvement.

- Production: articulating current understanding and how to apply this.

We initially mapped how both the local (primary and secondary) and international PGCE programmes are/would be delivered in terms of the above learning types, marking the frequency we would use each learning principal (see below).

Firstly, we focussed on the current local PGCE course, plotting in red before mapping the proposed PGCE international course in black. We were then able to understand the difference in terms of delivery approach between the two sister courses which going forward would help to inform our planning.

Local vs international

In terms of production and practice curriculum elements, we saw a close synergy between the local and international offerings. Assessed teaching practice benchmarked against the UK Standards, assessment points throughout the course and masters level assignments being compulsory components.

In comparison to the international programme, we believed the local PGCE is perhaps slightly more acquisition focussed, mainly due to the increased face to face university element including access to conferences and workshops across campus.

In relation to the strengths of the proposed PGCE international course, we were looking at deeper expectations around collaboration, discussion and investigation. These elements would be promoted in terms of the face to face induction, online ‘live’ sessions and self-study preparation.

Conclusions

It was clear from the curriculum development session that the key Pedagogical tenets of the PGCE international programme are to be centred on collaboration, discussion and investigation. Ensuring these elements are woven through the module planning will be a key focus.

The session also helped cement thoughts around the unique selling points of the programme. Whilst the main ingredients of the new course will be international in outlook, alignment to our domestic offering will also provide a ‘local’ UK flavour.

October 15, 2018

Journal Review – The Profession – Chartered College of Teaching – Georgina Newton

In its characteristic practical and accessible style, the Chartered College of Teaching has produced a handbag/backpack sized journal, capturing some of the very best evidence-based practical advice that any teacher (not just new ones) would benefit from reading.

In its characteristic practical and accessible style, the Chartered College of Teaching has produced a handbag/backpack sized journal, capturing some of the very best evidence-based practical advice that any teacher (not just new ones) would benefit from reading.

Articles which draw attention to matters such as assessment, planning, subject knowledge, behaviour, inclusion and progress help to flesh out the best practice in each area of the Teachers' Standards without getting bogged down in too much detail. The three handy "take aways" at the end of each section are a very practical set of ideas for personal reflection.

Underpinning each of the articles is a respect for each teacher's individual ability and need for reflection. No two classes or lessons will ever be identical so the most applicable help for teachers is that which identifies common elements but allows individual practitioners the chance to amend, adapt and apply as necessary. This, in turn, addresses the need for teachers to develop both the feeling of and an actual sense of agency - to choose and design what and how they teach. This is essential for teacher humanity, pride and professionalism (Rycroft-Smith, 2017).

Starting this practice at the beginning of their careers may well bear fruit in terms of their longevity in it, too. Studies have shown that teacher agency along with praise, recognition and good staff/leadership relationships are important in addressing teacher attrition (Newton, 2016).

So, in starting with a publication for teachers at the outset of their careers it seems that the CCOT has found a "very good place to start".

The articles on making the most of mentoring and professional judgement, in my opinion, should be read by all school practitioners, in particular the definitions of "practitioner research" as a systematic process of reflection on our practice, trying out new ideas and evaluating the impact of what we do explains a pragmatic and clear approach to teacher CPD.

I can certainly point to times in my 21-year classroom career when school CPD took on this format and, for me, was inspirational and effective in refining my practice.

The important message which comes across through all the articles in this journal is "teaching is worth it and you are worth it". The links, examples, graphics and sequencing of the material all contribute to this message. It is clear that teaching is alive and well in this newly-formed self-supporting professional structure.

If you aren't yet a member of the CCOT it is highly recommended. NQT membership is free and will give you copies of The Profession, Impact (the termly journal covering essential matters), access to over 20,000 research papers and the national Early Career Teacher Conference in October. A package of enriching goodies too good to miss, which will help make your first years in teaching enjoyable, successful and sustainable.

References

Newton, G. (2016, November 15). Why do Teachers Leave and What Could Make Them Stay? Retrieved August 4, 2017, from BERA Blog: https://www.bera.ac.uk/blog/why-do-teachers-quit-and-what-could-help-them-to-stay

Rycroft-Smith, L. D. (2017). Flip the System UK. Abingdon: Routledge.

October 08, 2018

What is your teaching philosophy? – Danielle

PDP Task 2 – What is your teaching philosophy? How has this originated and can you evaluate how your educational touchstones will impact on the teacher you aspire to be?

At the heart of my teaching philosophy is the belief that all children can achieve their goals, irrespective of their background, circumstance, or ability. When I was younger I used to have epilepsy; a condition which some of my teachers saw as a hindrance. At the end of my secondary education, these teachers remarked that I would not succeed in a science-related career. As a teacher, I never want a child to feel like they are unable to succeed in something which they are passionate about. In an attempt to ensure that this does not happen, I try to tailor my teaching to adapt to the needs of my pupils (TS5). For example, all of my PowerPoint presentations have been adapted for students with dyslexia by using a font which resembles handwriting, and a background which is coloured depending on the specific needs of the pupil. Both of these amendments were implemented as a means of making reading easier and learning more accessible. Furthermore, in order to help pupils who needed support with calculating surface area:volume ratio due to difficulties with visual-spatial reasoning, I made animals out of multi-link blocks (Taylor & Jones 2013). These animals removed the need for pupils to visualise 3D structures in their heads and provided examples which they could count by marking faces with a sharpie.

As part of my PhD, I regularly helped secondary school students to synthesise paracetamol and aspirin. These experiences taught me that I was highly passionate about teaching science to others. As part of this process, I worked closely with the outreach co-ordinator for the University of Warwick. When thinking about my educational touchstones, this teacher resonates closely with who I aspire to be. Whenever he taught, he always addressed students with such enthusiasm and provided them with a wealth of knowledge that left them feeling encouraged and motivated. Promoting a love of science and inspiring my students is definitely the type of teacher that I want to be. According to Hobbs, enthusiasm for what you are teaching is crucial for engaging and influencing your pupils (Hobbs 2012).

To achieve this goal, I have used activities which are engaging and varied (TS1) (Goodwin and Hubbell 2013). For instance, in a Year 8 lesson, instruction sheets and dice were used as a means of motivating pupils to learn about the carbon cycle. A similar strategy was used to teach a Year 9 class about the History of the Periodic Table. According to a formal lesson observation, such activities were successful in securing a high level of student engagement. Further to this, I set up and ran a Science Club within one of my placement schools, with the aim of cultivating an interest in science beyond that of the National Curriculum (TS3). As part of this club, students designed paper rockets and tested their flight stability and aerodynamic performance. By testing a range of different conformations, the students were able to identify that fins were needed to avoid the paper rockets spinning out of control. Pleasingly, as the Science Club progressed, more students were asking to join. This indicates that I managed to foster and maintain pupils’ interest in science (TS3).

References:

Hobbs, L., 2012. Examining the aesthetic dimensions of teaching: Relationships between teacher knowledge, identity and passion. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(5), pp.718–727. Available at: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0742051X12000224.

Taylor, A.R. & Jones, M.G., 2013. Students’ and Teachers’ Application of Surface Area to Volume Relationships. Research in Science Education, 43(1), pp.395–411. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-011-9277-7.

Goodwin, B. & Hubbell, E.R., 2013. The 12 Touchstones of Good Teaching: A Checklist for Staying Focused Every Day, Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=lgpRBAAAQBAJ [Accessed on 06/05/18].

October 01, 2018

Vocabulary – Kate Glavina

I have always had an interest in and fascination for the power of vocabulary and remember well the excitement I felt as a child when I successfully tried out a ‘new word’. For example, in Junior 4 (now Year 6), I was introduced to the word ‘consequently’ and wove it into my conversation as often as I possibly could. When my sister, later, introduced me to ‘subsequently’, I was quite transported.

The power of a rich vocabulary and its impact on educational attainment is well documented. In her book Proust and the Squid, Dr Maryanne Wolf reflects on the absence of literacy and asserts that: ‘When words are not heard, concepts are not learned.’ The OUP has recently published a language report entitled 'Why Closing the Word Gap Matters' in which the point is highlighted that the size of a child’s vocabulary is the best predictor of success on future tests and children with a poor vocabulary are three times more likely to have mental health issues. The motivation for Robert Macfarlane’s recent, beautiful publication The Lost Words was a reaction to the revised edition of the Oxford Junior Dictionary (2007) which had ‘dropped’ around forty common words related to nature, such as bluebell, heron, bramble, fern, heather… Macfarlane describes his poems as ‘spells’, intended to be spoken aloud to ‘summon lost words back into the mouth and the mind’s eye’. The importance of a wide vocabulary and the best approach to teaching young children seems a relevant, current debate.

Reflecting on the findings of Ofsted’s 15/16 review of the curriculum and assessment in English, HMI Sally Hubbard reported at a NATE conference (Autumn 2017) on the reading curriculum and in particular asserted that the most-able readers in the primary schools visited, lacked understanding of words that linked to ‘knowledge’. She stated that teachers should use their subject expertise to ensure that pupils can cope with vocabulary that is ‘lexically dense’ and ‘content-specific’. She emphasised the importance of vocabulary and ‘knowledge of the world’ and teachers’ appreciation of how language and understanding the world go hand-in-hand. She talked about the demands of the Key Stage 2 Reading SAT and the requirement for children as readers to be able to, amongst other skills, be able to explain the meaning of words in context and explain how meaning is enhanced through choice of words and phrases.

These language demands were viewed further through the focus of the research by Isabel Beck around Three Tier Vocabulary. In summary, Tier 1 words are those common ‘everyday’ words to which children have plenty of exposure and which quickly become a part of their vocabulary. Tier 2 words are not used commonly in conversation, but are more often found in written materials, whether fiction, information or technical texts. They will be used, for instance, by authors to enhance a story, for literary effect (e.g. misfortune; dignified; faltered) or to provide particular detail in an information piece (e.g. relative; vary; accumulate). Tier 2 words are not context specific but highly generalisable – and often express concepts that children are familiar with but in a more sophisticated or nuanced way. Tier 3 words, by contrast, are technical terms specific to content areas (e.g. lava; circumference; aorta). Recognised as new and ‘difficult’ words, they are often defined by the author of a text and sometimes scaffolded as through a glossary. All three tiers are important for comprehension and vocabulary development although Tier 2 and 3 words require more ‘deliberate effort’ than Tier 1.

In considering this model, Hubbard argues that teachers are good at giving attention to ‘Tier 3’ words - will anticipate them in their planning and offer children explicit instruction around them through such strategies as pre-teaching key words; providing a Word Wall; exploring spelling patterns, word families, derivations. What is lacking, however, is attention to Tier 2 words which, being ‘non content specific’, children will encounter in multiple contexts. It is therefore crucial for teachers to engage children in a consideration of words across different contexts. As an example, Beck outlined an occasion where she read nursery children a story in which there featured the word ‘reluctant’: Lisa was reluctant to leave her teddy bear in the laundrette. In exploring this concept, she asked the children to share a time when they had felt reluctant to do something and the children typically replied thus: . I’d be reluctant to leave my teddy at my friend’s house; I’d be reluctant to leave my drums at my step-mum’s… All of the examples offered by the children, related to leaving something behind. Beck modelled further: I’m reluctant to ride a roller-coaster. Some children are reluctant to eat spinach. Could you tell me something you’d be reluctant to do? Much to her delight, one child replied: I’d be reluctant to change a baby’s diaper.

In light of the survey findings shared by Hubbard, I thought it would be interesting to use the lessons I observe as a Link Tutor, as a lens through which to consider the idea of Two Tier vocabulary instruction. The first opportunity was a science lesson with Year 1. The Learning Objective shared with the children was displayed on a whiteboard: I can describe the physical properties of a variety of everyday objects made from different materials. The trainee asked the class what was meant by the word ‘variety’. One child responded by saying it meant ‘lots’ and the trainee agreed and moved on. In reflecting on this interaction with the trainee after the lesson, in light of the Three Tier Vocabulary model, we established that ‘variety’ fitted the classification of a Tier 2 word – i.e. it is not context specific but used in a range of different contexts. The trainee could appreciate that instead of confirming ‘variety’ meant ‘lots’, as though the words were synonymous, there was, in fact, rather more ‘unpacking’ to be done around the definition. Having a number of something (even ‘lots’) is a prerequisite for having variety, but does not in itself mean there is necessarily difference between them. Considering other contexts in which the children might have encountered the word ‘variety’ would have been valuable as well as then making the link between the meaning of the word in the context of the learning objective and the resources on the children’s tables to be investigated in their science activity.

In a different school, I observed a trainee teaching a grammar lesson to Year 5. The objective was To Build Cohesion Within A Paragraph. The trainee began the lesson by asking the class ‘What does ‘cohesion’ mean – talk to your partner.’ After a moment or two, she took an answer from one child who said ‘time connectives and conjunctions’, to which the trainee replied ‘Yes, well done.’ Of course, this isn’t in fact the meaning of the word ‘cohesion’ - the child had quite cannily offered a phrase spotted at the top of the worksheet on his desk which related to the grammatical terms one might deploy to create text cohesion and which was clearly going to be the focus of the next exercise . The trainee did not explore the meaning of the word further – neither in a wider context, nor in a grammatical one. Part way through the lesson, the trainee drew the class together for a mini-plenary during which she asked a particular pupil to read their work aloud and then asked ‘How can you make that sentence cohesive?’ After a pause, the child said ‘I don’t know’. As an observer, I sensed that the difficulty lay in the fact that the child didn’t know what ‘cohesive’ meant and without further comprehension of the term, could not articulate a reply. Reflecting on the lesson afterwards, the trainee agreed that anticipating the need for discussion around the term ‘cohesion’ would have supported the children’s understanding of the task, their engagement with it and the progress made during the lesson. Out of interest, I asked the trainee how she would define the word herself – in what other contexts she might encounter the word - and she gave me a lovely response: I think of the word in the context of RE – in relation to ‘unity’ – and also the idea of cultural cohesion – and I also associate it with ‘glue’ and sticking things together – oh no...is that ‘adhesive’? In terms of exploring nuance and a range of contexts, this trainee was well able to see the wide applicability of the term cohesion and the merit, in future, of better anticipating those words at the planning stage of a lesson.

In conclusion, I have found this focus a very interesting one as there has always been an instance of a Two Tier word occurring early in the lesson (e.g. ‘equivalent’ when exploring fractions in maths; ‘map’ when discussing story structure in English) the exploration of which has been pivotal to the children’s understanding and, crucially, their capacity to make progress by the end of the lesson. We need to be alert to Tier Two vocabulary – anticipate it when planning – give it attention during teaching. To this end, Jo Dobb and I have created new SBTs for the 18/19 cohort of core Primary and EY PGCE trainees. These tasks will build on work we will do with the students on the ‘taught programme’ to introduce the concept and model the process. We are confident it will have a positive impact on children’s vocabulary development and subsequently (one of my favourite words) on pupil progress. Finally –since we have been thinking about vocabulary development, let me leave you with a topical book recommendation – take a look at ‘What A Wonderful Word’ by Nicola Edwards – a wonderful gift – or indeed why not treat yourself?

Abigail Ball

Abigail Ball

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…