All 73 entries tagged E-Learning

View all 300 entries tagged E-Learning on Warwick Blogs | View entries tagged E-Learning at Technorati | View all 3 images tagged E-Learning

June 20, 2006

Four case studies in copyright and intellectual property rights

Follow-up to More about how you can use copyrighted material for free in criticism or review from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

Case Study 1

During her summer vacation, a lecturer in aesthetics visits the Fundacio Miró in Barcelona. It is a very relaxed gallery, with no major security presence and none of the ugly signs that pollute the nearby MNAC gallery with warning of criminal charges to be levied at anyone who breaks the rules. On seeing one of the paintings, the lecturer realises that it could form the basis of a lecture. She quickly takes a photograph of the painting. No one seems to mind. Later she finds an internet cafe, and logs into her module web pages on Sitebuilder at Warwick. She uploads the photo of the artwork, and adds it to the resources page for the lecture in which she plans to discuss the artwork. The page has its security permissions set so that only Warwick staff and students can access it. The image will only be used in teaching of the module.

Has she done anything wrong? If so, what do you think she should have done?

- As Joan Miró only died in 1983, it is likely that copyright still belongs to the Miró estate, which I suspect means the Fundacio Miró.

Is she then covered by a permitted use?

- The permitted use for (group) research or (personal) private study does not apply in this case, as she is using the image in teaching.

- She could argue that she is using the work for criticism or review, but this would depend upon the exact way in which it is used.

- However, she is using more than an insubstantial part of the artwork, in fact she is reproducing the whole work, although she does not remove the need to refer to the original work.

- But she may well be infringing upon the Moral Right of the author in representing his artwork through a poor quality copy. Artists seem particularly keen on using this clause to prevent their work being digitised.

However, there is a further consideration:

- Even if the copy were to be considered as one of the permitted acts, the gallery would almost certainly have imposed as a condition of entry a ban on photography and the reproduction of its works. This is common practice. Galleries are firm in their defence of these contracts.

What then should she have done? I suspect that the Fundacio Miró are quite generous towards the use of their images in teaching. They may well have provided permission to use a good quality copy free of charge or cheaply. The lecturer should have contacted the gallery and sought permission. This would also respect the Moral Right of the artist.

One final point: the image was on an access controlled site, which probably means that she would not have been caught. However, it is not impossible. And furthermore, she really should try to do the right thing.

Case Study 2

A research student attends a lecture on cognitive science by a visiting lecturer from Edinburgh. Many of the colleagues in the student's research network are unable to attend, for either timetable reasons, or because they are at other universities. It all seems very exciting, a new theory about how intelligence is founded upon its extension into materials and tools in the world beyond the brain. The visiting speaker is particularly excited about some new examples that he has discovered that will answer the many existing criticisms of such a theory. He explains that he will very soon be publishing a book that details these ideas in full. He expects this to be the most important book in its field ever to be published. However, despite his excitement, he feels the need to try out some of the ideas with a small number of other researchers. He therefore elaborates upon these new discoveries in his lecture. The research student finds that these ideas fit very well with his own work. He also knows that his colleagues at Warwick and beyond will find new impetus to their research from these new ideas. It offers a chance to really bring together all of these people. After the lecture he quickly finds a computer and writes a blog entry to explain everything that he has learnt. His friends all across the world are able to read about these great new ideas right away.

What will the effects of his actions be? Would you do anything differently?

Case Study 3

A lecturer is an active member of a discussion forum hosted in the Warwick Forums system. The forum is open to all members of the university. It is a very popular forum, with people from across Engineering and the Warwick Manufacturing Group participating. Such a diverse collaboration of knowledge and skills often leads to new perspectives on old problems. One particular problem seems to be quite intractable, so the lecturer posts a long description of it on the forum. She already has some possible solutions, but just needs a little input from elsewhere. The tactic works, an MSc student offers an unusual insight that inspires a solution from the lecturer. A journal paper follows, along with, a year later, an unusual email from the exams secretary. The student has been accused of plagiarising from the journal article. The plagiarism seems to be quite clever, but the ideas are the same and a few sentences are shared. When the lecturer looks at the student's essay, it appears that some of it has been copied from the forums discussion.

What factors should be considered in resolving this? What could have been done differently?

Case Study 4

A researcher regularly writes short articles and publishes them on her blog using Warwick Blogs. The articles usually attempt to make some connection between her work on the history of the Middle East and current events in the news. The blog becomes a popular read for many specialists in the area. After some time, the lecturer is contacted by a friend who asks how she managed to get her work published on the web site of a slightly extreme Islamic student's organisation in France. She is baffled. On looking at the url, she finds a blog like web site, mostly in Arabic, with one of her articles sitting in the middle of the page, surrounded on all sides by arabic, of which she can decipher nothing. The article is about the Arab Revolt of 1916, and the coordinated attacks on trains that were an essential part of it. She is a little concerned, as she has absolutely no idea what kind of context her work is being presented in. It is attributed to her, with a url link to her blog, but it seems to be a very different article when presented out of its original context.

How do you think this happened? Do you think it is likely? Has anything illegal been done? How would you respond?

Something similar to this has in fact happened to me. One of my blog entries appeared on an Arabic language web site, I don't really know the context as I cannot speak Arabic. But I have absolutely no reason to believe that it isn't one of the vast majority of worthy Arabic sites on the web. So I really do not mind, and in fact am quite curious as to what they find interesting in my work.

Has anyone got any other opinions on these cases?

June 16, 2006

More about how you can use copyrighted material for free in criticism or review

Follow-up to Neat tricks for dealing with copyright? from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

Note: I am not a lawyer. You should not regard this article as providing perfect and sufficient advice.

Permitted use for criticism and review

British copyright legislation includes some significant protection of what could be conceived as "free speech". The use of copyrighted material for criticism and review is an essential component of this.

Clearly the legislation is vital in such an extreme case. But it is also intended as a general support to activities of criticism and review. It supports all such open debate, and is thus essential in supporting the very essence of arts education and research.

Limitations on fair dealing for criticism and review

We can therefore safely reproduce copyrighted materials if such an act is essential to criticism and review. There are, however, restrictions. The first of these is stated clearly by Raymond A Wall in his very useful book Copyright Made Easier:

Copying or quoting a sufficient extent or significance to render consultation of the original unnecessary or less necessary would be unlikely to be judged 'fair' in court. Wall 2000, p177

There are two aspects to this limitation. The most easily understood of these is the limitation on the quantity of material copied. Most people are familiar with the idea that they cannot copy an entire book, play, movie, song or other such production. There are commonly accepted definitions of this regarding the quantity that can be copied from a book. However, this is in fact much less important than the second aspect. It isn't the quantity that really matters, it is the significance of the copied excerpt.

Note that "significance" is entirely a matter of judgement, until the damage has been done. Any use of copyrighted material in criticism or review may be challenged by the copyright holders in court. There is therefore always a risk in using this defence.

Protecting the moral rights of the author

Whenever we use a copyrighted work for criticism or review, we are still compelled to protect the 'moral rights' of the author. For example:

Any reproduction must be accompanied by sufficient acknowledgement. Wall 2000, p177

We must also ensure that we do not distort or misrepresent the author or their works. This limitation is quite significant. Authors can argue that the presentation of an edited or extracted part of their work presents it wrongly. Artists frequently use this moral right to object to their work being presented on screen. Again this is a matter of judgement. Our best defence is to seek advice from the author as to what is acceptable, and to explain in the criticism or review that the presentation of the artwork in the reproduced sample is only a partial representation of it.

June 07, 2006

Neat tricks for dealing with copyright?

Follow-up to E–learning Research: copyright and the principle of fair dealing in education from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

Firstly a statement: I'm not a lawyer! This may be imperfect advice, so do not rely on it, make your own judgements.

Richard started the day by stating that, although he has lots of expertise in the field of IPR and copyright, he is not a lawyer. So the person responsible for managing rights in the UK's most content dependent university is just an ordinary person on an ordinary salary. This kind of work can be done without constant recourse to expensive lawyers. As the session proceeded, Alma and Richard demonstrated how they are constantly required to give advice as to what is acceptable. It seems that they have a good body of knowledge and experience upon which to safely proceed, getting legal support where necessary.

Alma then stepped through, in an effective way, the implications of UK copyright legislation. The details of what is not permitted were clarified. This was quite familiar to me, except for the details of two 'restricted acts':

- providing means for making infringing copies;

- authorising infringement.

I asked for more detail on these, raising a familiar example:

What if a university provided a web publishing facility to all of its staff and students, and one of them used it as a means for making infringing copies?

The response was that the university should have:

- a set of terms and conditions, agreed to by all members, that prohibit such acts;

- mechanisms for guiding users in understanding the legality of their acts;

- an effective complaints mechanism, and a swift "take down" policy, so that illegal content can be removed as soon as a complaint is received.

Warwick does well on points 1 and 3, which are relatively easy to do. All members must sign an agreement. We also have an effective complaints and take–down procedure (in Warwick Blogs there is a Report a Problem link, and in all systems content is easily attributable). However, the second point is much more difficult. We assume that users understand blatant copyright abuse, but it seems that they are poorly educated on the more complex issues such as breach of moral right.

Permitted acts – using copyrighted material without permission

And so we first received the bad news: copyright is both strict and pervasive. Alma softened the blow by explaining some of the 'permitted acts' that allow us to use copyrighted material without necessarily having permission. It should be noted at this stage that:

- the existence of permitted acts should not be used as an excuse to avoid having an effective copyright clearance process, as permitted acts are in fact quite rare, and always need to be thought about carefully.

As I have explained in the past, the most well known permitted act, the right to use content for private study or research, does not actually permit the use of copyrighted material in teaching or online. I'm surprised by just how often people who really should know better get this wrong.

There are some useful permitted acts. For example, we can copy an 'insubstantial' part of a copyrighted object. This is commonly taken to simply mean a specific percentage or a certain number of words. There are some accepted conventions, but unfortunately they are misleading. For example, if I were to reproduce online the most significant 400 words from a book of a thousand pages, I would be quite seriously in breach of copyright. If my act of copying damaged the commercial success of the book then things could get quite expensive for me.

A second permitted act is potentially much more useful. It may be possible to reproduce copyrighted material if that reproduction is for the purpose of criticism or review. This again is a matter of judegement. The copied material must be essential to the purpose, not incidental, although it is not necessarily the case that the review has to be about the copied material.

I want to investigate just how far this permitted use can be taken. I suspect that much of what happens in the Arts Faculty is in fact criticism and review. The key is to make sure that the content is used in this way. For example, if a lecturer uploads a copyrighted image to a web site, but immediately makes a critical assessment of that image, is that then a permitted act? Also, it must not breach the moral rights of the author. I shall investigate.

In the second half of the course, Richard explained the copyright clearance process employed by the Open University. Content creators at the OU are expected to refer all possible uses of copyrighted material to the rights management team. The OU employs full time specialists to perform this role. Obviously the OU is content dependent, but as other universities become more digitally native, they should consider if they also require such an office. As Richard explained, there role goes beyond copyright clearance, they must help content authors prioritise. They suggest identifying early on which copyrighted material is most central to the content, so that more time and money can be spent upon obtaining clearance. The clearance process itself is greatly assisted by having full time experts who understand contracts and have many contacts within the business.

What does it mean to be digitally native?

We do a lot of work on the assumption that the wider use of ‘e-learning’ or ‘learning technology’ is necessarily a good thing. This of course needs some explication and justification. Our founding claim is that learning, teaching and research (LTR) can be significantly enhanced with the application of appropriate digital and online technologies by staff and students for whom those technologies are self-evidently obvious and natural.

LTR activities are usually collaborative. The use of technologies within such collaborative activities requires that the various partners are comfortable and capable with the tools used. Each collaborator can be skilled to a varying extent, with some super-users leading the way. But experience shows that the more widely the skills are spread, the better the uptake of the technology, and the more effective it is in enhancing the activity.

The concept of ‘digitally native’ is useful. My conjecture is that the more people who are ‘digitally native’ the more effective the technologies can be in enhancing these collaborative activities. Steve Carpenter (Sciences E-learning Advisor) introduced me to the term ‘digital native’, and its antithesis ‘digital immigrant’. The terms, it seems, were invented by Marc Prensky (CEO of Games2Train and author of Digital Game-Based Learning). You can read more in his article Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants in which he makes the more dramatic claim that there is a mismatch between digital native students and the digital immigrants who teach them. I’m not going to assess this claim. Rather, I want to give a more explicit definition of what it means to be digitally native, as a means to outline a vision of where I think the university should be in five years time.

What qualifies someone as being ‘digitally native’? A simple set of skills, employing the best available technologies. The digital native does the following:

- produce and store quality content (text, images, audio, video, diagrams, databases etc), with consideration of its presentation online;

- share content online, in an appropriate location and with appropriate security constraints (considering legal, moral and inter-personal issues);

- where responsible, maintain, update and remove content;

- structure the relations between content items;

- classify and describe content to make it more meaningful and useful;

- locate, assess and use shared content;

- edit and extend, comment upon, filter, and recommend to others;

- record and reflect upon their own work and that of others as represented by their online activities;

- create,define and manage networks of other online people;

- build up an electronic portfolio and profile;

- present samples of online work;

- reflect upon this work, in collaboration with others, so as to identify strengths, weaknesses, and actions for improvement (informally, or formally as peer review).

My assessment of the Arts Faculty at Warwick is that it is edging slowly towards being digitally native, but progress is slow, and in some areas non-existent. This pace is surprising, considering the technologies and services that are available. We have a reliable and increasingly extensive web architecture (Sitebuilder, Forums, Blogs), which is well supported and increasingly ubiquitous. There are also many isolated examples of successful technology enhancement of learning, teaching and research. But these remain isolated. Prensky would argue that the big blocker to a digitally native university is that the majority of the people who do the teaching and set examples to be followed are in fact digital immigrants.

June 02, 2006

The death and rebirth of the MLE?

Writing about web page /caseyleaver/entry/mle_learning_platform/

Writing about an entry you don't have permission to view

Yes, the rotten decaying body of the corporate Managed Learning Environment stinks. We should bury it.

Hold on a minute, i detect a heart beat. Can it be revived? Should it be revived? Perhaps it will come back having undertaken some kind of near–death moral transformation. Born again.

Sorry, i'll get to the point. We are seeing the emergence of a kind of self–assembled, loosely coupled, lightly managed learning environment (LCL–MLE?). This is made possible by the increasing ubiquity of RSS data feeds, single sign on, and keyword tagging, along with service development and provision strategies such as agile development and managed diversity.

The idea behind the old fashioned centralist MLE (OFC–MLE?) was that the user could see a range of data about the learning process, all in one place. So they would see their timetables, list of courses, marks, tasks, courese content etc all together. And furthermore, it would be possible to join them up. OFC–MLE systems would contain all of this data in a single repository, as a tightly coupled system. Years of painful experience demonstrates that such monolithic systems are hard to develop, difficult to maintain, and harder still to engage the wide range of people and processes. The answer has been to grow more independent services, with responsibility distributed more widely and designed to meet the requirements of each type of user (academics, students, administrators, communications professionals).

The trick is for each of these two make its content available openly to the people and systems who need to use it, but in a filterable, secure and timely manner. This adds up to a LCL–MLE. And that means a data environment in which people can:

- advertise information so that it gets to the right people (using directories and search based upon keyword tagging);

- find relavant information (using directories and search based upon keyword tagging);

- recommend information to others (by building their own del.icio.us style directories or by adding additional tagging);

- combine information in a single location, and present it in a useful way (see how RSS feeds are blended in the left hand panel of the E-learning at Warwick web site.

- allow the user to return information to the systems from which it was harvested, or to get diverse information to interact;

The last of these is enabled by Single Sign On, which is the key to allowing people to easily go from information, presented anywhere, to functionality that allows them to act on it. For example, on a page that I have constructed from a combination of sources, I could see that there is an interesting event happening, and easily add that event to my personal calendar without having to go off into a separate system.

Keyword tagging also contains some revolutionary force. Remember how OFC–MLE systems where built on the assumption that learning processes were constructed by a single individual (or well coordinated team) with a strong overview of all of the contents and connections that should be contained in the learning experience? That has always been the antithesis of the kind of research based learning (RBL) that makes a top UK university what its is. RBL is more like a mentoring and guidance model, in which less centred and hierarchical teams develop a shared understanding of the direction in which the students should be steared, and then input resources, links to resources, and feedback that does the work of moving the students in the right direction. The student is themselves expected to gradually (or sometimes quite quickly) take over the helm and navigational responsibility. OFC–MLEs tend to work against this. But imagine a technology that allows the teaching team to create and select resources, and then annotate, tag and connect them for the students. The students can then explore these resources, and even create their own tagging, annotation and networks of them, to be shared with others or even assessed by the teaching team.

The E–learning Advisor Team are already working on several projects that exploit these possibilities. Our web architecture (Sitebuilder, Warwick Blogs, Warwick Forums etc) provides many of the tools that we need to make this a success.

See this interesting paper on Connectivism presented to Google by George Siemmens.

May 30, 2006

Blog styles for better academic writing

The appearance of a Warwick Blogs blog can be altered by its owner using a language called CSS. This allows for the appearance of elements on the page (such as the calendar) or classes of elements (such as the entries) to be modified. The Admin –> Appearance page of your blog contains a text area (bottom of the page) into which you can enter your custom CSS. It also contains a warning that should be taken seriously:

Caution: If you don't know what CSS is or how you use it, then you should probably leave this textbox empty.

Despite this rather forbidding note, there are some things that you can do very easily. You can, for example, create custom styles to indicate extra semantic class differences between various items of text in your blog entries.

I have defined text types for:

- Overview, used as the first paragraph of each of my entries.

- Conjecture, used when I am making a claim to be assessed.

- Definition.

- Example.

- Technote.

- Conclusion.

If you look at one of my recent blog entries using the Firefox browser (as any sensible person would), then you will see various paragraphs that are marked up as having one of these specific roles. In Internet Explorer 6 (an older browser) each of these types of text looks the same, with a grey background and a dashed edging. In the more recent Firefox, however, each type of text is prefixed with the name of the type of text.

If you want to have a go at this, you need to add two extra styles to your CSS for each of the types of text. For example, for overview I have added:

.overview {margin-bottom:10px; padding:3px; border: 1px dotted #A1A1A1; font-family: georgia, Times, serif; background-color: #EAEAEA; }

.overview:before {content: "Overview: "; font-weight:bold; font-style:oblique}

The first of these styles changes the background, border, layout and font. I could, if I wanted, use different colours and fonts for each type of text, but I personally like to keep things visually simple. The second style adds the 'before' pseudo element. In order to apply this to a paragraph of text in your blog, you need to wrap that paragraph in special tags that apply the style to the text:

<div class="overview">This is an overview text.</div>

I also have some styles that change the background colour of selected phrases, allowing me to highlight them with some extra meaning. For example, I can mark them as key terms or just apply a yellow highlighter pen:

.highlighter {background:yellow}

.keyterm {background:#BBE9F6}

In these cases, I use a different tag to contain the text to be effected:

<span class="highlighter">Highlighted text</span>

Highlighting is particularly useful when I am working with a qoute from a text.

May 28, 2006

Academic connectors and academic dissectors

Kay's analysis of my own work quite rightly places me towards the connector end of the line, meaning that my intellectual habits tend towards seeking out related phenomena in distinct realms, looking for connections, and searching for a common underlying dynamic. Other people tend towards the dissector extreme, they are primarily concerned with analysing a single phenomena by dissecting it continually into more fine–grained constituent parts.

I'll leave that conjecture open and unassessed, as there are two more immediate questions that interest me:

- Are the two modes of operation in fact just two aspects of the same intellectual process? – inseparable;

- Does the application of one without the other lead to empty meaningless results?

- Are our learning technologies capable of supporting each mode in the right way and at the right time?

Connective synthesis and disjunctive synthesis

The notional connector person and their counterpart dissector are characterised as such because they tend to make things following one particular pattern. The product of their creativity being conceptual structure, developed within and expressed by various forms (texts, diagrams, programmes, maps).

The creation of concepts, of whatever pattern, is an act of synthesis:

With the two syntheses defined, the inseperability of connection and dissection (question 1 above) is clear. But why should there be character types that favour one of the modes almost exclusively over the other? Surely the best approach would be to recognize the importance of each synthesis in its own time and place, whilst retaining a critical stance? There are no doubt many reasons why people become inflexible in their thinking, becoming trapped within an obsessive dissection or a delirial search for connections. I would like to raise the possibility that our learning technologies may be part of the problem.

To that conjecture, I added the clause 'most current learning technologies'. I do believe that there are a couple of technologies that do encourage this kind of non–linearity, namely wikis and concept maps. Both of these tools allow us to do the following:

- Create a set of topics in relative isolation from each other (the MindManager concept mapping tool even includes a 'brainstorming' tool to assist with this).

- Create a proposed structure drawing upon these topics.

- Extend the structure with new topics, or old topics further dissected.

- Create new connections between the topics.

- Revise topics without drastically effecting the overall structure of connections.

- Revise the structure without drastically effecting the individual topics.

- Track revisions and authoring actions.

In these ways, wikis and concept maps actually work to promote a more effective combination of the three syntheses (connection, disjunction, conjunction), and open that process up to the critical view of both students and tutors.

May 26, 2006

Podcasting, seminars and e–portfolios

Last night I recorded a seminar as part of the What Is Philosophy? project. During the seminar discussion, I made some comments that I suspect may play a key role in my research. It took just a few minutes to edit my comments and the subsequent discussion into a small file, and upload it into my eportfolio and blog. You can listen to this by clicking on the button below:

This gave me a thought:

Perhaps in the near future, as e–portfolios become more common within higher education, amongst the various snapshots of a student's academic work, we will see podcasts of seminars.

May 25, 2006

E–learning Research: a Deleuzian method for the evaluation of virtual learning environments

VLE

A series of questions must be addressed:

- What is an environment composed of?

- What varies between different environments to create differing environmental regimes?

- To what extent is a virtual learning environment (VLE) an environment?

- How do VLEs vary, so as to create different regimes?

- Are certain such regimes preferable to others?

Environments are composed of filters

In this way behaviour and geophysical processes connect through an environment that is the assemblage of all of these interoperating filters over time. This is more or less true of any environment. The physical built environment is well understood in these terms, but also consider how an online application with a variety of user accessible functions filters a pool of back–end functionality. In return, the end user filters out irrelevant or inaccessible functionality. Over time these functions may even die off through lack of interest or the application of an agile development process that in some ways copies evolution.

The case of the polar bear is presented above in a simplified manner. There are many complications and possible combinations of filters that offer other kinds of environmental regime. Reality presents a range of regimes and blends of regimes, many of which occur across widely differing regimes. For example, in his work on the 'extended cognition' model of cognition, Andy Clark proposes that a kind of mangrove effect may well be a significant assemblage in the generation of new ideas. Clark describes how a new mangrove swamp begins by a single plant floating in the water, with extended roots that may catch hold of both food and other plants. This kind speculative drift is another assemblage of filters that may be a viable regime in some environments. For example, in the online world we may use a blog to float a part–formed notion. Effective use of semantic tagging and discovery tools may attract further content to the idea, allowing it to grow. It may also allow it to connect to other complimentary ideas. Over time as the mangrove–idea grows, it attracts further connections and taps into greater pools of energy.

The mangrove is an example of a regime of filtration that the philosophers Deleuze and Guattari have called rhizomatic. There are many other regimes, many of which are diagrammed in their book A Thousand Plateaus. These regimes include arborescent assemblages, which operate by applying rules of exclusion that form hierarchical branches of filtration; a familiar model in both software design and social anthopology. Other regimes of importance include:

- Gadgets, or filters that follow a reproducible and generalizable design;

- Animal bodies (which are gadget–like, but less portable and generalizable);

- Familial structures;

- Mythologies;

- Geological and sedimentary processes.

We therefore have the first of our tools for understanding the construction of environments: regimes of filtration. As has been demonstrated, the principle applies across environments, and in some cases we see regimes re–occurring in quite different settings.

Environments are composed of networks

A second and relatively rare aspect of some environments can best be understood through the behaviour of a more complex animal: the honey bee.

Karl von Frisch

Waggle dance, plume theory, filters

James Gould Cognitive map

Abstraction

some filters are symbolic or digital, redundancy

codings to promote autopoiesis through symbiosis

simulations to accelerate judgement

dissimulation to exploit weaknesses in the simulations of others

the relation between filters and networks is a matter of ecology

Environments are actual

quantification and index

registers of modification

progress

the actual tends to impose limits on differentiation

Environments are virtual

signal can be quantified, the carrier (the assemblage of filters) is more complex and sensitive – a continuum

movement, freedom, creation

whole system evolves continually

different elements evolve at different speeds

differential speeds provide registers for understanding the different elements

Smooth and striated space

Emergent actuality

Instructional VLEs

Research VLEs

May 24, 2006

How to write a communications strategy

Purpose

One of the key aims of a communications strategy is to ensure that the best 'channels' of communication are used for each of the different 'stakeholders' with whom one must engage. The use of inappropriate channels is a common and sometimes serious mistake. For example, I do not wish to be told by my doctors surgery that I must use an online diagnosis form, I want to actually talk to a real person. Unbelievably, the obsession with technology has actually caused such obvious errors of judgement. One must think carefully about audience, and match channels to them carefully.

Stage 1: stakeholders

The first stage of the process is to identify the range of "stakeholders" with whom communication must be carried out. There may be some groups within the university for whom this is straightforwards. However, I suspect for the majority there are a range of different and sometimes conflicting groups to be catered for. So what of the E–learning Advisor Team? Consider our rather broad and general aim: to encourage wider and more effective use of learning technologies throughout the four faculties. Obviously the agents of this change are our principle stakeholders. But we should also consider everyone who will beneift, as they are ultimately those who will judge our effectiveness.

Casey provided us with A3 sized grids on which to record our ideas. Along the vertical axis, we listed each of the stakeholder groups. On my grid I added the following:

- Lecturers - techies and early adopters. Lecturers who are prepared to adopt new learning technologies without much prompting or convincing. This group presents us with an easy but not necessarily significant or sustained win.

- Lecturers - followers. Perhaps an unfair description, as the majority of lecturers simply do not have a great deal of free time to try out new approaches. They have to use well tested and understood techniques.

- Lecturers - resisters. This group actually puts effort into opposing the introduction of new learning technologies, even though no one is actually forcing them to do anything. Yes, they really do exist, and can exert a formidable effect within departments.

- Graduate research students and post-docs. A group that I take very seriously. They do a big share of the teaching, as well as being users of learning technologies for private study.

- Taught students. There is some controversy about whether we need to communicate with taught students. It could be argued that this is the responsibility of the relevant lecturers. However, I believe that it is necessary and valuable for us to work directly with taught students. At Warwick we aim to encourage students to act independently, taking personal responsibility for their skills and technologies. The Learning Grid is a brilliant example of this approach.

- Departmental IT. Some departments have their own IT people, who act as key agents of change (or stagnation in a few rare cases). This is more common in the Sciences.

- Departmental administrators. Another significant set of agents for change. The Business School's e–learning team had a strategy of working closely with administrators. This is said to be a very effective approach, leading to excellent integration of admin and e–learning systems, something that IT Services has failed to do.

- IT Services. The people who run the services upon which we rely must be informed as to the significance and effects of their services.

- Central service providers. For example the Library and the Warwick Skills Programme, who are themselves keen to adopt the best technologies, and who may also effect change within departments as they demonstrate successful applications.

That is quite an intimidating range. Perhaps we should consider cutting some of the stakeholders out of the plan? For example, we could take the easy route and focus upon the techie/early–adopter lecturers. But then we risk alienating the vast majority of lecturers by only ever addressing the needs and interests of individuals who are already unique and eccentric. Alternatively, we could simply address the silent majority of lecturers, the 'followers'. That would be a hard and perhaps impossible slog, in which we may fail to encourage and communicate any good examples of the use of learning technologies. Probably the best solution is to prioritise, and work with each group where they offer the best strategic return.

Stage 2: channels

Assuming that we do have to communicate with each of these groups in some way, the next step in formulating a communications strategy is to consider the range of available 'channels' of communication that are available. Once that I started on this list, I quickly realised how many we do regularly use, and just how diverse they are. My list included:

- The E–learning at Warwick web site.

- Content on other people's web sites.

- The E–learning Forum.

- The E–learning Blog.

- Personal blogs.

- Email, personal.

- Email, list.

- Telephone.

- Booklets and leaflets.

- How to guides.

- Flyers.

- Posters.

- Billboards.

- Personal contact.

- Coaching sessions.

- Presentations within other meetings.

- Seminars and workshops.

- Conferences.

- Novelty items (I mean fridge magnets, drinks mats etc).

I'm sure there are even more, but I ran out of room on the A3 grid, upon which they were plotted along the horizontal axis.

E–learning Team Comms

Now, with the stakeholders and the channels plotted, one can consider matching the latter to the former, that is to say, ensuring that the appropriate channels are used with each group of stakeholders. This immediately throws up some key issues. For example, I expect that content presented via blogs could be more accessible and interesting to undergraduates. However, I have in the past made the mistake of expecting a moderately 'resistant' lecturer to read a blog! My experience is that such people actually expect and demand to be dealt with on a personal face–to–face basis.

Thanks Casey!

April 20, 2006

E–learning Research: tuition fees, market differentiation, and the role of e–learning

It is unusual to see full-frontal nudity in the pages of the Daily Telegraph. Even more shocking that the model in view should be a dear old friend. Unfortunately, this Monday (17–04-06 – abbreviated online version available), there seemed good reason to laugh at the indelicately exposed flesh of that alleged emperor of the education world: the British Arts Degree. The claimed justification for this sudden revelation? They want to charge £3000 a year for the privilege. The ever to be trusted investigative methods of the Telegraph hacks are ringing the first of what will be many alarm bells. They are asking: £3000 for what? Six hours of lectures and seminars a week for someone studying History at York. Outrage. Eight hours a week and you get a psychology degree from Bristol. Even the old Freudster couldn’t have dreamt up that one.

The story was all too superficial, but let us put that aside for a moment and consider the implications of the article’s underlying perception for Warwick. Then it will be possible to consider what this may mean for e-learning.

Firstly, I am a new father, already contemplating university fees eighteen years from now (I am absurdly long sighted). The effects of tuition fees on my considerations are: for that kind of money my son could go anywhere. That is certainly not true, I imagine that a good American education is significantly more expensive. But I have the modern British attitude to debt: when I pay out sufficiently large sums of money I deliberately avoid thinking about the number of zeros on the end of the sum. I’m more inclined to dream about the magnificent product that I am buying. The consequence of this deliberate blindness to the level of my personal debt is that I do not notice whether I am spending £3000 or £10000. For evidence, consider my mortgage, a staggering and entirely unreasonable amount of money. Therefore, if I have to pay out lots of cash for my son’s education, I will go for the best available, or at least as much as my credit limit can handle. And if that also means he gets to go abroad, somewhere nice for me to visit, why not? Perhaps what will happen over the longer term is that the portion of an individual’s debt available for house-buying will decrease, whilst the portion to be spent on education will increase. A £20,000 decrease in money available for the mortgage is quite insignificant. Moving that £20,000 into the education debt would make a very big difference. Even so, America may still seem just too expensive, but then there are plenty of alternatives. Australia for example is a dream for many young people in Britain, and they do actually have some decent universities. Perhaps we should set up a campus in the Pacific? In any case, now that I am a consumer of higher education, with money (or rather debt) to spend, I feel more financially empowered than I was as an undergraduate in 1991 having my fees and rent paid for me. That empowerment makes me think: what cool things can I get for my money? Expect to see the appearance of a magazine title just for people like me: Which University?

The implication of tuition fees for Warwick? Undergraduate degrees are now placed into a complex and global market. After years of trying to stay ahead of the other First Division Russell Group universities, with a distant hope of promotion to the Premier League, the game will suddenly change altogether. At the very least the range of feasible and thinkable options available to the school leaver will grow (despite the current number of institutions, there are still very few genuinely different options for the aspiring middle class kid). Competition between the providers will increase. The need to differentiate the product will become pressing (already noticeable in the proposed new Warwick Learning and Teaching Strategy, which seeks to differentiate us as thoroughly “innovative”). The market (or at least its self-appointed guardians, including the Telegraph) will seek out variables of comparison between the products on offer. For example, it is possible to compare the amount of “contact time” (lectures, seminars etc) that a student gets for their £3000 at the various institutions. The Telegraph have done just that. Expect a league table of contact time to be published very soon.

Students and their parents have always had their own methods for comparing universities and making choices. At the first stage of consideration the decision is made for them: which of the various leagues are they in: Oxbridge? Red-brick? Polytechnic? A small minority of students will then base their choice on the specific details of the courses on offer. Students with minority interests (theology, anthropology) will have little choice. For the majority of students, the next most significant consideration is lifestyle. Campus or town based? By the sea? Big City? Near to home or far away? Lively Student’s Union? Nightclubs? Girl-to-boy ratio? The choice has always been taken lightly in academic terms but with huge significance in the social aspect. Perhaps this will remain the case. The current orthodoxy claims that the typical undergraduate wants a degree course that simply offers them the required sheet of paper bearing the figure “2.1” along with three years of fun and “personal development”. In this case the terms of the competition are simple: which university can guarantee the 2.1 whilst offering the best social experience? I contend that Warwick may well lose out to Sydney in the second of these variables. For now the guarantee of a safe degree result may override this. But as the members of this globally scoped market wake up to the new competition, they may well all start to focus their energies on the guarantee of reasonable academic success. In which case who wins? Sunny Sydney with its glorious beaches and bronzed bodies? Coventry? Expect to see the Which University? guide looking ever more like a holiday brochure.

Some will of course dissent from this trend. Perhaps in eighteen years time my son will realise that he is to be expelled from the family home and packed off like a convict to the land of Oz. I will seek at every opportunity to instil him with a sense of adventure, but should that fail, he may oppose my plans by opting to join the thousands of young people who simply choose not to go away to university (he can stay, but will have to live in the garage). The Open University is increasingly popular, as are the many smaller more local universities offering easier and more certain access. This is in many cases a rational choice, not just for economic reasons. Many students simply cannot cope, at 18, with leaving home. The OU may be the best thing for them (note, I came to Warwick at the age of 20). Expect the appearance of a league table of drop-out rates and mental health problems to be published very soon, as the consumers wise up to this being an important consideration.

The traditional market for universities like Warwick would then be significantly eroded in two directions, with some students globalising, whilst others become even more sedentary. In either case Warwick seems to lose its footing. We can attempt to combat this with glossy brochures and friendly open days, but as competition becomes more intense, and the market more discerning, the bottom-line story will come under closer scrutiny and really must hold up effectively. And all the time every other fish in the pond will offer a pretty picture of nice residences and a lively social life. Such things cease to be a differentiator and instead become commodified.

These trends will no doubt be the certain outcome if consumer attitudes remain as present. But the Telegraph article may indicate (or be leading) a significant shift. At least a large sub set of consumers will start to behave more intelligently, with a detailed appreciation of what makes the difference between institutions and their offerings. Expect, at least in the short term, a rise in the number of courses that combine the safety of a traditional UK institution with more exotic destinations abroad (these are already a big part of the Arts at Warwick). Also expect to see prospective students seeking clarification and verification of claims by British universities that they offer a special kind of educational experience, somehow resulting in superior graduates. What exactly is it about a degree at a certain institution that makes it worth the money more than any other? This is the real drive behind the Telegraph article.

The obvious claim is that limited contact hours equal poor quality education, and vice versa. This is countered with the notion that arts students benefit greatly from even a small quantity of high quality contact with top experts, whilst developing independent skills of their own: so called “research based learning”. This is in many cases the “exactly” of “what makes a specific degree better”. I have heard this argument at Warwick, and indeed have on occasion used it myself. Unfortunately as a differentiator and mark of quality, this concept has become dramatically devalued and will not stand up to the kind of scrutiny applied by the Telegraph. Professor Anthony King of Essex University knows this to be the case. He makes the obvious point that 18 year old students do not have the required skills to operate as independent researchers. Expect to see as a consequence universities differentiating themselves through well worked out, consistent and clearly branded undergraduate induction and skills programmes. Warwick MUST do this to keep competitive as an undergraduate provider. However, such curriculum developments are expensive. And the question of who bears the cost has to be settled. It may be born by agencies external to the subject specialist academics, by for example a central undergraduate skills programme separate from academic departments. However, we then risk the dilution of the degree programme away from subject specialism and academic expertise, precisely the things that we claim give its special value. At the other extreme, the cost of curriculum development would fall upon the subject specialist academic. This would be a difficult choice at a time at which increasing pressure is being placed upon such academics to produce high quality work to be evaluated by the Research Assessment Exercise. It may be that research academics simply cannot do the extra work of redeveloping the curriculum at this time.

The immediate quandary facing Warwick, given the changing market conditions, is then how can it differentiate its undergraduate offerings with some special characteristic, such that its claims:

- are significantly attractive to prospective students within a global market;

- represent value for money;

- can be understood by prospective undergraduates (and the media that tells them what matters) without too much effort;

- do not add an unbearable overhead to existing resources (academics);

- can be maintained as a distinct advantage over the competition for a significant length of time.

By definition, there is no simple solution. If points 1 to 4 were easily achievable, then every one of our competitors would achieve them right away, leaving us with no advantage: we would fail on point 5. As always, any solution to the problem of successful differentiation in competition requires a blend of strategies that:

- meet the popular demands and expectations of the market;

- do so in some uniquely special and un-commodifiable way;

- reduce cost whilst bringing new value to all participating agents.

At this point the common reaction is to reach for a copy of the Oxford Dictionary of Techno Wizardry. Look under E for E-learning perhaps. But don’t get too excited. There are some possibilities, but we will not find a panacea. Technical solutions can only be part of the answer to the kind of problems that I have outlined. For example, we could create an online induction course that requires no input from academic staff. However, if it worked really well and delivered valuable education, it would not be delivering an education valuable in a way specific to Warwick and its academia. In fact it would soon become commodified, copied by every other university. Technical solutions always imply that we must keep innovating and improving, as they are easily copied by the opposition. The best solution is to pair the technical solution with something else that cannot be copied by another university. Something unique and situated in the culture and community of the place, which must itself develop to meet the new challenges alongside the introduction of new technologies.

At this point I should make clear exactly what I am not advocating, for e-learning already has a bad name from the wrong kind of coupling of technological and cultural change. Many within education and beyond have sought to force change through technological development. This however very rarely works, unless you have the power to force everyone to use the new technology. Unfortunately, this tactic is usually the last resort of institutions who do not have that kind of power. Paradoxically, they hope to attain this authority surreptitiously through the introduction of technology, which of course relies on having such a degree of power (the strategy thus collapses into circularity). For example, the rapidly fading generation of Virtual Learning Environments (Blackboard, WebCT, Learnwise) have been adopted by some institutions as a means of introducing quality assurance frameworks by stealth. The idea being that the VLE “encourages” lecturers to document their teaching activities and to record the work of their students in an online location easily accessible to university authorities. Administrators would then be able to drill-down into institutions to examine every detail of what is going on, without even leaving their desks. Of course no British university has either the power or the will to force academics to cooperate. Consequently there are a lot of very empty VLEs out there.

Instead, we require a different kind of technology strategy, one that takes the best aspects of the unique community and culture of the university, and supports, enhances and extends them to provide a significantly different and more valuable undergraduate experience. Importantly, this cannot be done in isolation from development in the practices of the people involved in teaching undergraduates, as they are the key source of value. So we could see the introduction of a superb new technical tool for supporting undergraduate learning, for example a blog system, but that must be connected to and validated by the involvement of the specialist academics that are Warwick’s special value. Currently the Warwick Blogs system does give us a small advantage over our competitors in the overall undergraduate provision, but it is not in any way rooted in the academic specialism and culture that makes Warwick unique. It is potentially comodifiable. Expect to see Oxford Blogs, Cambridge Blogs and so on at some point soon. The next difficult question, one that I do not yet have sufficient answers for, is how we develop our e-learning provisions so as to stimulate the required cultural development within the university. I have a strategy, but not yet the required tactics. Any suggestions?

April 19, 2006

E–learning Research: copyright and the principle of fair dealing in education

Firstly, what is meant by "fair dealing"? The notion refers to exceptions in the application of copyright that may be claimed as applicable to specific breaches of an author or artist's rights. In a limited set of situations, one could offer as a defence in court that a breach of copyright is "fair" under the accepted meaning of that part of the copyright legislation. Whether a specific breach of the law is "fair" or not is always a matter of judgement.

What then is allowable? Under "fair dealing" it is the case that certain educational activities that breach copyright are acceptable. These exceptions are however very strictly defined. Stepping outside of the boundaries leaves one with no legal defence. The boundary is simple, as Raymond Wall explains in his very useful Copyright Made Easier (Aslib/IMI 2000): one may break another person's copyright by making a copy if that copy is to be used for either research or private study. If used for research purposes, then the copy may be circulated amongst the researchers, or they may each make their own copies. If used for private study, the copy may be used privately by a single "student":

'Private study' has become accepted as excluding group or class study… p.169

Notice that the shared use of copies in the research context does not apply to the study context. Copies cannot be made for and circulated to classes of students. This may be quite a surprise. We have become familiar with the following activity:

…someone possessed a photograph of a painting, taken for research or private study, and subsequently showed it to a class… p.273

For example, a slide of an artwork being presented to a class. And as Wall argues, we are justified in considering this not to be a problem:

…it is doubtful whether the rights owner would object… p.273

But the fact is that in doing so we have no legal right or recourse to "fair dealing". If we then seek to transfer this scenario to the digital world, making a scanned file of the artwork and "showing" it to the class via the internet, rights owners understandably get a lot more upset and a lot less charitable. Digitisation enables the rapid production and circulation of multiple copies, beyond the original good intentions of the person who originally scanned the image – bad news for rights owners. One might then consider claiming that the digitised image is circulated via the internet for research purposes and not for private study. This almost works. Unfortunately, we should remember that "fair dealing" is not a guaranteed right, but rather a possible defence that may be available if indeed the dealing were fair. However, if the digitised image were to become available beyond the research group, and multiple copies are made for purposes beyond the research, then the rights of the copyright owner have been infringed unfairly.

There is then a chain of misconceptions that lead people from acceptable fair dealing for private study or research, to the abuse of copyright online. And subsequently I must often explain that just because you can share an image for research purposes or show an image in a lecture, you cannot therefore digitise that image and put it on your web site.

Does this then mean that we can do very little with digital media? There are two further possibilities that may provide the rights to use the media. Firstly, there is the lapsed-time defence. A moderately complex set of rules governs the persistence of copyright after the creation of object or the death of the artist/author. Unfortunately this is not at all straightforwards.

In the case of an artwork, current ownership may lie with a gallery or other body that has licenced the right to make a copy to a specific person (or excluded others from the right under specific contract, such as the right of the public to enter the gallery). The person who then creates the image of the artwork then holds the copyright of the image, but under contratcual terms imposed by the gallery. When reproducing an old artwork, by for example scanning a postcard, one must respect the copyright of the person who created the image of the artwork that is being reproduced.

In the case of a sufficiently old text, although no specific reproduction of it can be copyrighted (even a different presentational form or typography), the text may contain notes or translations that are original to a more recent agent, and therefore part of their rights.

The final and most painful solution is to obtain permission, from the rights owner, to reproduce their work. In some cases, we are lucky to find that someone has already done the work for us. As Wall explains, the exclusion of group or class study is:

…in fact the basis of photocopy licensing of multiple copying in the education sector. p.170

But in many cases, including almost all digitisation, there are no such agreements or agencies. In these cases, permission must be sought on a item by item basis. You simply have to do the tedious work of contacting artists/authors and asking for permission.

Copyright is then a significant blocker to the use of artworks and texts in the arts. The assumption that such educational use is "fair dealing" is false. Without rights agreements and agencies to help, keeping legal is a difficult task. My next investigation on the subject will be to consider the agencies and agreements that are available now, or in the near future, to assist.

Comments and corrections are most welcome (especially if they are from lawyers and free of charge).

April 06, 2006

E–learning Research: Why academics blog (or not)?

Follow-up to Research Plan: ideas for researching networking, narrowcasting and broadcasting by bloggers from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

Why this matters

I think I have some answers to these questions. Or at the very least, I have a good way of thinking about the problem that may render it answerable. But first I assume you are not necessarily convinced that it matters. In response I offer two arguments:

- Answering the question of why academics don’t blog may give us a deeper insight into academic attitudes and behaviours. This knowledge is transferable to other learning technology development problems;

- I believe that weblog technology (along with other new web tools) has the potential to dramatically enhance the “academic environment”, if applied intelligently.

So there you have my agenda and motivation. I hope you agree on its significance.

Understanding the desire to blog

We should ask more widely of all bloggers: "why do you blog?”. The first and key step in answering this question is: "who do you blog for?" – "what is your intended (or implicitly assumed) audience?" The intention of a blog may be to inform, enrage, impress and so on, but those effects are always relative to and motivated by the imagined effect on a given audience. The blogger blogs so as to have these effects on an audience. Sometimes, as in a solely reflective blog, there is an audience of one, the author themselves. Even so, the motivation is to have an effect on that audience.

At this point, as I suggested in an earlier entry, we can use one of the core concepts of communications and design studies: narrowcasting versus broadcasting. The question then is put more specifically:

- Do you write for a specific actual audience (known nameable people)? – In which case you are engaging in formal narrowcasting (the most formal narrowcasting will apply privacy controls to keep unknown people out);

- Do you write for a specific virtual audience (unknown but clearly classifiable people, such as "all philosophy students")? – In which case you are engaging in informal narrowcasting.

Or:

- Do you write for no specific audience, considering your audience to be anyone who finds your blog? – You are engaging in broadcasting;

- Do you write content that appeals to a broad and loosely specified audience, but seek positive feedback from an identifiable and narrow audience? – You are broadcasting, but through the filter of what is in effect an informal or formal editorial presence.

Blogs may in reality be a mix of these attitudes, although not necessarily within the same entries. For example, my blog contains informally narrowcasted entries about the philosophy of Gilles Deleuze, as well as broadcasted entries about my baby. Some blogs are particularly effective at leading a general audience into an interest in very specialized topics, or vice versa. But quite often a blogger will make an assumption, usually a received and unconsidered assumption, about their audience, the audience appropriate for a blog, and stick to it. And from where is this assumption receieved? I suggest two key sources, each transmitting a different and contradictory assumption, and resulting in very different kinds of blog:

- The traditional broadcast medium (newspapers, radio, television) who present blogs in terms understandable and significant to themselves. Looking at the coverage of blogs in these media, one would assume that blogging is a broadcast medium, aiming to reach an unspecialized and general audience (in fact the blogs that they like are the ones that are capable of being translated into the traditional broadcast media);

- The network effect of friends who blog enticing their friends to also blog. In this case the tendency would be to blog for your friends, in response to your friends, and therefore to narrowcast.

Which of these two influences is the most prevalent? Examing the list of recent entries in Warwick Blogs usually indicates that the former may be more potent. Indeed it would appear that most bloggers are trying to be one-person-broadcast-media, with the majority of entries about topics of very general interest and requiring no specialist knowledge. There could be narrowcasted topics that we can’t see dues to privacy controls, but in fact I know that this is quite rare. We could also assume that the authors of these broadcasted entries are expecting a set of known readers to appreciate them, whilst still writing in an essentially broadcast style. I suspect that this says something about the kinds of social relations that exist between these bloggers. They are after all mostly students and hence only together for a very short and uncertain period of time, perhaps not long enough to develop deeper and more specialised shared interests.

We may also ask the question of the blog system itself: is it biased towards narrowcasting or broadcasting? Have a look at the Warwick Blogs homepage and see what you think. More importantly, what does a set of blogs (and their aggregation) implicitly say about the purpose of blogging? My guess is that a brief look at Warwick Blogs would give you the impression that bloggers write more for an unspecialized and general audience. The highly discursive nature of blogging (especially at Warwick) encourages this. The listing of topics that have received many comments reinforces this. The assumption is then that blog entries are written to prompt discussion amongst a general audience.

Understanding the academic desire to blog (or not)

Now consider the nature of "being an academic". What is the most significant feature? I would say specialization. In fact I would argue that universities exist as places in which quite extreme specialization can take place. This is so extreme that even two people in the same department may not have much of an understanding of each other's work (modal logic is a mystery to me). To an outsider that may seem bad. But it is in fact the very reason for giving people the time and space required to explore and innovate. Furthermore, I conjecture that most academics would respond to finding any spare time in their busy diaries by doing activities to work further on their specialization. If you're not an academic, and you don't believe me, think back to what it was like being an undergraduate. Did you get the sense that each individual academic was trying to pull you into their own particular specialized field? This is even more so for graduate students, as lecturers seek to recruit doctoral students (or at least sell their own books).

Asking again the question: "why should an academic blog?" – So far we have no answer.

Of course academics cannot stay in their silos of specialization permanently. They occassionaly have to crawl out of the cave and communicate their work to a slightly more broad audience. Ideas do need to be tested. They also need to be funded. Could they do this in a blog? Yes. Would they? Probably not. Consider just how carefully managed this process of academic exposure usually is, and how much work is required to get it right. The peer reviewed journal is one of two mechanisms for communicating academic work in a managed way; a tighly controlled way. Conferences are a little more wild and risky, but even so are regulated with high expectations. I know of academics that could talk brilliantly about anything at any time, and yet they still cancel conference appearances because their papers are not perfect.

From this perspective, the project of academic blogging looks doomed. Perhaps that is why very few academics turn up to my workshops on blogging? (In comparison to sessions on tools that help with their own private research).

Academic blogging 2

I seem to have done a fairly good job of demolishing the idea that blogs can be useful to academics. And yet I still stand by my statement that:

weblog technology (along with other new web tools) has the potential to dramatically enhance the “academic environment”, if applied intelligently.

The weblog is, after all, a powerful tool for recording and archiving the development of ideas, for exploiting that archive, for selectively exposing it to others, and for developing an identity and a presence. All of these activities are vital to the academic process. The key to using the technology is in understanding how it can be used to address a controlled audience (from an audience of one, the author, to the whole world). This is a matter of using the features built into the software, as well as exploiting writing techniques that more clearly define the audience and hence manage engagement with it. For example, one keep a blog containing entries about a specialised topic, sometimes stating that an entry is “just a conjecture” and other times stating that it is “more conclusive”. You can alert colleagues to entries that they will be interested in, asking for a response, even a formal peer review. But you can also expose these entries to the world, allowing for chance encounters with other academics, in the same or a related field. You may also find that over time words that you use, ideas that you develop, in your blog become more widely accepted. It could even attract funding.

However, for this to become common practice, changes must occur:

- We need to change people’s perception of the purpose of blogging, from a broadcast medium to a medium that is sophisticated enough to combine broad and narrowcasting as required;

- There needs to be more widespread adoption of the techniques for managing audiences and writing;

- The advantages of blogging for academics in specific situations need to be explicated and communicated, with real examples.

I shall explore this in another forthcoming entry.

Your comments on any aspect of this entry are most welcome.

April 05, 2006

E–learning Research: Factors for choosing e–learning projects

Follow-up to E–learning Research: Achieving success in e–learning development from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

I am therefore seeking:

- guidelines on selecting projects, such that those chosen are more significant and continually successful;

- means for encouraging the formation and completion of projects (by staff and students) that meet those criteria.

My first conjecture is that a successful e–learning development project requires at least the cooperative endeavours of IT providers (including development and support), the University (that is, services and interests that are global to the whole institution), and the end users (the staff and students who will be affected by the development, and who play a central role in making it happen, usually as part of the project team).

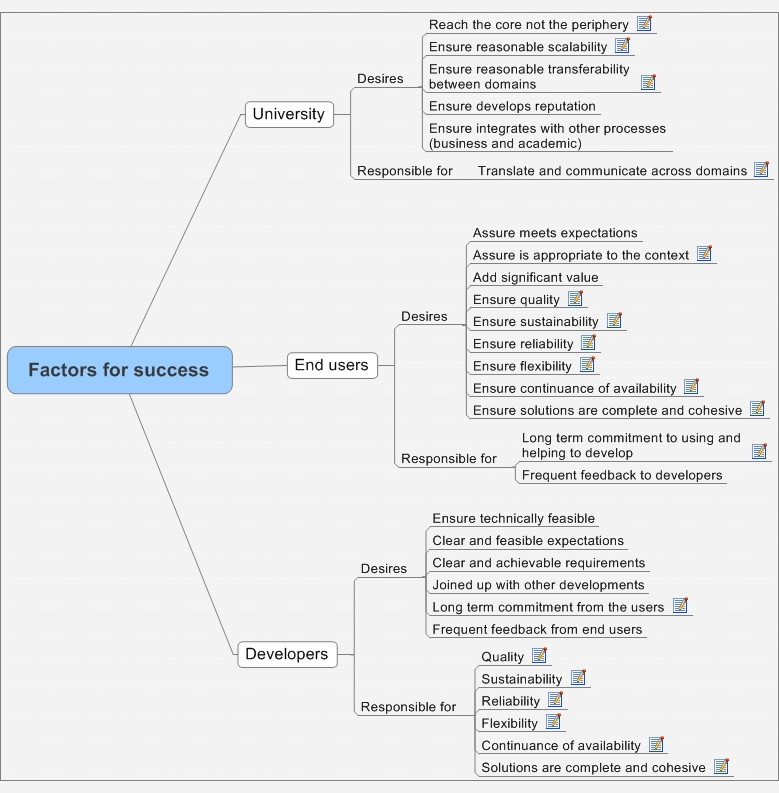

Each of these parties has a set of desires that make the development feasible and worthwhile. In return they have certain responsibilities that must be met for their own desires or those of others are to be met (and hence for the development to be successful). These desires and responsibilities form the factors that contribute to the success of a development. I am trying to create a comprehensive account of these factors. Here is the concept map node so far:

It should be immediately apparent that for all of this to be assured (rather than merely accidental), there needs to be a cooperation of the efforts and interests of the many people involved. At this point we should note that some people do believe that we simply should not worry about this problem. Coordination of all of these people and factors at the same time being too difficult. Rather, we should just stand back and allow new practices to emerge from a diverse network of people all innovating with the available toolset, and actively feeding new requirements to the IT providers and the University. The idea is that the near–viral force of "network effect" will result in positive change over time. This may indeed sometimes be true, and certainly is when countenanced on a very large scale (e.g. the whole internet). But within a University there just are not enough users with enough time and desire to innovate. Furthermore, demands on the time of core users (those who can assure that a new approach is permanently adopted) are so great as to prevent deeper innovation, affecting and improving core activities. Consequently innovation and innovators tend to be peripheral, thus failing on desire 1.1.1.1. Note that although there may be small and quite visible innovations, transferable across domains (1.1.1.3), they are not significant innovations and do not add significant value (1.2.1.3). I conclude then that deeper more widespread cooperation is essential for significant and cost–effective development (the Learning Grid was planned, many cooperated on it, it did not emerge out of the chaos).

(Note on strategy for Rob Johnson: a successful guerrilla operation is only achievable through the deployment of large numbers of operatives, each with plenty of time and committment. That is what distinguishes guerrilla war from terrorism).

Consistent and ongoing commitments are absolutely necessary, as is good communication. The big question concerns how to assure that this happens (problem 2 stated above). The common solution is to form projects that have their own strong distinct identity, and which unite the various partners. How can I do this?

My single greatest problem is in getting sufficiently consistent committment from end users, including staff and students, especially those who are core project members. If success is to be achieved through effective projects, then I must find a way of forming good projects that meet the list of factors for success. I shall now work on this question.

March 30, 2006

E–learning Progress Report: looking for a new job

Follow-up to E–learning Research: Achieving success in e–learning development from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

What are we trying to achieve?

I define the goal quite simply: the adoption of good new technologies by lecturers and students to enhance the teaching and learning process (which at Warwick includes research activities). The effort in adopting the new technologies should be justified by the value that they add, and not negated by any disruption that they introduce to existing practices. The end result should be to contribute to Warwick becoming a world class university.

How can I contribute to this?

Perhaps the best place to start is by asking: what am I good at? That is answerable by identifying what, out of the (far too many) things that I do, people value the most.

Rob Johnson identified something important today during a discussion of a planned skills and PDP development project in History. In response to his description of the project, I raised a few critical questions that need to be answered in considering and planning the project. Without first answering these questions, the project could be undermined. People often tell me that they value this input.

Secondly, I was able to demonstrate how the nature of the project and its deliverables might change in response to these answers. Most importantly I could suggest techniques (pedagogical and otherwise) and technologies that might address the identified problems. These suggestions were based on a mix of experience (they had been used elsewhere) and rational conjecture (they were new ideas that sound feasible).

So to summarise, what I am recognised as doing well:

- help people to think and plan critically;

- suggest possible solutions.

Note that there are other things that I could potentially do well, but for various reasons beyond my control, I cannot reliably contribute them to e-learning development.

What can I not contribute?

These positive contributions are good and valued. They create specific requirements, including:

- helping people to answer the critical questions (through deeper investigations);

- the absolutely fundamental requirement to provide a cohesive and complete set of tools and technologies that can be used to meet the requirements to an acceptable extent;

- the need to provide good and relavant examples illustrating possible solutions (academics are constantly asking for good relevant examples from real teaching).

Unfortunately, I am finding that I cannot satisfy all of these requirements at the same time, and am not getting sufficient help in doing so. Specifically, I find that:

- I do not have enough time and resource to help them to answer the critical questions through deeper invesitgations;