Roman Numismatic Memory Part 2: Gaius and Lucius as principes iuventutis

|

| Aureus showing Gaius and Lucius |

The second in our Augustan bimillenium series continues the theme of Roman numismatic memory. One of the key themes of Augustus' principate was the problem of succession, and initially Gaius and Lucius Caesar were advertised on the imperial coinage as Augustus' heirs, as principes iuventutis. Between 2 BC and AD 4 (or perhaps later), the mint at Lugdunum (modern day Lyon) struck aurei and denarii showing the two brothers veiled and accompanied by shields, spears, and priestly symbols (Lactor J58, RIC Augustus 205ff).

That these coins, and the images on them, were viewed by the Romans as 'monuments in miniature' as well as currency, is demonstrated by the later use of this image. During the reign of Trajan a series of coins were struck that modern scholars call the 'restitution' coinage. This was a series of coins that bore the imagery of a much earlier coin type, either from the Republican or early imperial period. These coins celebrated the earlier coinage of the Romans, and Trajan himself is named and honoured as the 'restitutor' (just as an emperor may have been honoured for restoring a building or other monument in Rome). Why these coins were struck, and why particular coins were chosen to be celebrated over others, still remains a mystery to scholars. One of the current ideas is that these coins were struck as the older coinage in circulation was being recalled and melted down. Given the Roman conception of coinage this was a destruction of a monument in miniature, so the 'restitution' series was struck to counter this. Another idea is that the coins may have formed a gift for noble families at the time.

|

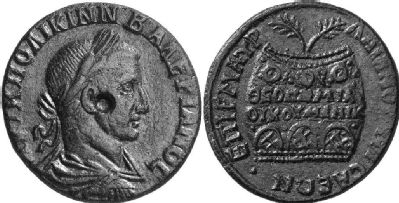

| Restitution coin struck under Trajan (?) |

In this context we should note a 'restitution' coin issue that honours the earlier coin of Augustus showing Gaius and Lucius. The coin in question reproduces Augustus' earlier issue exactly; unlike the other restitution coins of Trajan, he is not named on the coin as restitutor. But Augustus' portrait on the obverse of the coin is of Trajanic or Hadrianic style; this is not an Augustan period coin. Because of Trajan's restoration of other earlier coinages, most scholars place this piece in the reign of Trajan (AD 98-117). What this coin reveals is that Augustus' numismatic imagery was more than just decoration of the currency. The Romans observed, recorded and recalled Augustus' imagery at a later date. Why this particular type was restruck under Trajan remains a mystery, but this, along with the other restitution coinages, would have served to connect the emperor with Rome's past, and its first emperor.

(Coin images reproduced courtesy of Classical Numismatic Group Inc., www.cngcoins.com)

Clare Rowan

Clare Rowan

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

This month's coin was chosen by Joe Grimwade, a second year undergraduate at the University of Warwick. He chose his 'Coin of the Month' after attending the British Museum's Numismatics Summer School, and is about to begin working with Warwickshire's Museum Service on their Roman coinage.

This month's coin was chosen by Joe Grimwade, a second year undergraduate at the University of Warwick. He chose his 'Coin of the Month' after attending the British Museum's Numismatics Summer School, and is about to begin working with Warwickshire's Museum Service on their Roman coinage.

Loading…

Loading…