All 4 entries tagged Roman Britain

No other Warwick Blogs use the tag Roman Britain on entries | View entries tagged Roman Britain at Technorati | There are no images tagged Roman Britain on this blog

March 26, 2019

What's in a Hoard?

|

| The second Southwarwickshire hoard in a pot |

What indeed? Those living in Leamington may well have seen in the local press a report of the Warwickshire Museum’s intention to fundraise an initial sum of £3,000 towards the acquisition of a hoard of Roman denarii found in 2015 at a site atop the Edge Hill escarpment in south Warwickshire. This is in addition to submissions for more substantial funding from national bodies.

This is not the first hoard, though, that has turned up in the area, nor indeed the largest. One summer evening in 2008 a metal detectorist was on the point of giving up his unproductive search for material in an area a mere couple of hundred yards from the latest hoard, when his equipment began to register a significant find. Helped to unearth this by members of a local archaeological group who happened to be in the vicinity, it was eventually surrendered to the Warwickshire Museum and began its passage through the obligatory processes of the Treasure Act , where its status was established, and thence to the British Museum for valuation. At this point delay set in, principally because of the discovery of the Staffordshire Hoard of gold artefacts, but in time the hoard, valued at £52,000 (divided between the finder and landowner), became available for the Warwickshire Museum to acquire, something achieved thanks to grants by a number of national bodies. By this stage I had already had sight of the material and was able to begin cataloguing what turned out to be 1153 coins covering a range of dates from 194 BC to AD 63/4 in the reign of the emperor Nero. That denarii should remain in circulation for so long should come as no surprise since these coins were of high value (a basic soldier at the time earned 225 denarii a year), so were hardly small change. The catalogue was published as a British Archaeological Report (British Series) 585 in 2013 and is in the Warwick University Library (CJ 1101.I7). The hoard itself, and the pot in which it was found (originally sunk into the wall of a round structure) are well displayed in all their splendour within the Warwickshire Museum in the centre of Warwick.

Turning to the latest hoard there are important differences, which become only too clear when comparing the valuation placed upon them. To begin with, only 440 coins are involved, many of them heavily encrusted with soil or adhering together, having been buried beneath what might have been a threshold in an area where massive wall structures attest to a substantial Roman presence. As a result detailed identification of many awaits cleaning. As in the case of the first South Warwickshire hoard, though, there is a similarly significant proportion of coins dating from the Republican period beginning in the 140s BC, but importantly this second hoard extends its end-date into the reign of the emperor Vespasian, which began in AD 69. Significance? Well, it was preceded by a period of civil war following the suicide of Nero on June 9th AD 68 which saw a rapid turn-over of rulers – rapid measured in months: first Galba, then Otho and Vitellius before Vespasian won through. In addition to the coinages specifically issued in the name of these emperors, there are others anonymous in origin, together constituting a high proportion of the whole hoard, in fact. The resulting rarity of these coins with their short period of production, combined with the only slight wear they have suffered, means that the valuation given by the British Museum (even when the Warwickshire Museum has to find only half the total sum) outstrips that needed to purchase the whole of the earlier, much larger, hoard.

Stanley Ireland

Emeritus Reader

Classics & Ancient History

March 01, 2016

The Proculus Enigma: Have the history books been telling it wrong?

|

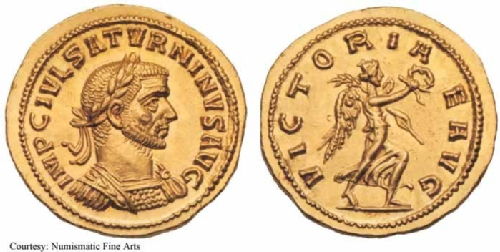

| Figure 1: Proculus Billon ‘Radiate’ (2.96g, 19.27mm) |

Before discussing this particular coin of the month, please forgive the Herodotus-esque digression on the context of its appearance. The day was November 7th 2012, and it began much like every other for one Yorkshire metal detectorist. The site he had chosen for the day had produced numerous finds in prior visits, most of which had suggested that he was walking in the footsteps of his Romano-British forebears. At this point, a thought may even have crossed his mind that his next find might be something other than Roman ‘grot’(derogatory archaeological slang for a heavily corroded and illegible Roman (typically) coin). Yet one object was, and all it took was just one signal, one hole, and one turn of the spade to unearth something virtually unique. However, this was not realised by the finder, Colin Popplewell, until he had posted images to an online forum. Further unbeknownst to him, his chance discovery would reignite a debate over the very existence of a third century usurper, and the contentious issue of his having struck coinage. The coin he found (Fig.1), provided an overt reference to a character by the name of Proculus having assumed the imperial purple. The legend reads:

IMP C PROCVLVS AVG // VICTORIA AVG

Emperor Caesar Proculus Augustus // Victory of the Emperor

This legend has only appeared once previously on a coin from a German collection, sold in 1991. Given its inherent rarity, it was unsurprising that this latest find was first met with scepticism, and then denunciation as a later forgery by some academic circles. However the author recalls a remarkably similar scenario occurring in the case of another usurper: Domitianus II. This case was only resolved in 2003, when a hoard from Chalgrove, Oxfordshire securely contextualized a coin bearing Domitianus’ name. Whilst a scenario such as this is yet to arise for Proculus, the reliable context of this second discovery compels my subsequent analysis to be conducted on the presumption that both examples are genuine.

|

| Figure 2: Both coins superimposed |

With only two coins, it would seem extremely difficult to produce a convincing argument for reinvestigation. However by overlaying images of one coin on top of the other, it is immediately apparent that the obverse and reverse designs are identical (Fig. 2). To a numismatist, this is a definitive indication that the same pair of dies produced both coins. This also strongly suggests that they were produced at the same workshop, if not even by the same hand (Morgan 2006: 175. For Domitianus II die linkages also proved crucial in authenticating both coins). Furthermore, the presence of intelligible legends on these two coins must indicate that they are also the product of a literate manufacturer. This particular factor also questions their potential alternative identification as so-called “barbarous radiates” (which also happened to be in contemporary circulation). However, most of these coins were low-grade imitations of official currency, and were seemingly produced by local, illiterate satellites. Consequently, the only plausible conclusion to draw from this appraisal of Proculus’ coinage is that they resemble the products of a coordinated and sanctioned series.

Having therefore established credentials for our coin, an assessment of other extant material can now be made, to establish whether this additional numismatic evidence for Proculus conforms to our historical impressions of the individual. The iconography of the coin itself helps to narrow our search of literary material to the later third century AD. This is evident from the size of the coin and the depiction of a radiate crown, which is emblematic of this period. Our main historical record for this period is the Historia Augusta, which is unfortunately notorious for its fabrication of stories (Dessau 1899). On account of its reputation, it is therefore unsurprising to find that it has provided two conflicting accounts for the character of Proculus. The first has him revolt in Cologne during the reign of the Emperor Probus (HA Life of Probus XVIII.5), whilst the second records his rebellion occurring in Lyon (HA Lives of Firmus, Saturninus, Proculus and Bonosus I.4, XIII.1). Other surviving references to Proculus are more questionable on account of their even later publication dates (Eutropius IX.17, Epitome de Caesaribus XXXVII.2). Consequently as the literary source most contemporary to the life of Proculus, the Historia Augusta must be consulted in contextual discussion of these enigmatic coins.

“One fact, indeed, must be known, namely, that all the Germans, when Proculus asked for their aid, preferred to serve Probus rather than rule with Bonosus and Proculus.”

HA Life of Probus XVIII.7

This suggests that Proculus usurped during the reign of Emperor Probus alongside a figure by the name of Bonusus, although no such indication of this partnership is given on our coins (the recognised dedication for multiple rulers is expressed by the number of Gs in ‘AVG’ - Proculus’ coinage has just one). More significant though, is the explicit mention of a location that accords with the find-spot of this latest example. Proculus is documented as having claimed the province of Britannia along with Gaul during his usurpation (HA Life of Probus XVIII.5), thereby assuming control of the Legion stationed in York (near to the site of the coin’s eventual deposition). However, in the view of the author, if the revolt had occurred during the reign of Probus, our examples of Proculus’ coinage would be stylistically out of date. This is owing to a coin reform enacted by Probus’ predecessor Aurelian, during the middle of AD 274 (Carson 1965, Weiser 1983). Alongside the addition of mintmarks and marks of metal or face value, the style of imagery depicted notably changed. Comparing the pre- and post-reform currency of Aurelian clarifies this point further, (Fig. 3 and 4) as design focus visibly shifts away from large draped busts to depictions of elongated necks wearing cuirassed attire. Whilst usurpation may have led to cessation of contact with the Empire, knowledge of monetary design appears to spread unaffected. Confirmation of this can be found in the usurper Saturninus, who apparently revolted in the East at the same time as Proculus did in the west (HA Life of Firmus, Saturninus, Bonosus and Proculus). His coinage (Fig. 5) depicts significant iconographic similarities to Aurelian’s reformed coinage, as the long neck and military uniform are his most noticeable features. Had Proculus’ rebellion been contemporary to Saturninus, one would expect to see more stylistic similarities between the two series. However, their style remains notably different, with Proculus’ strong facial dominance being more akin to pre-reform types. Consequently, iconography forces us to consider the possibility that Proculus coined, and thus usurped, much earlier than the literary sources suggest; prior to the Summer of AD 274.

|

|

| Figure 3: Pre-reform issue of Aurelian |

Figure 4: Post-reform issue of Aurelian

|

|

|

|

| Figure 5: AV Aureus of Saturninus |

Figure 6: Antoninianus of Tetricus

(AD 270-3), VICTORIA AVG, RIC V.2 141

|

Pursuing this theme further identifies a striking iconographic relationship between Proculan types and Tetrican coinage of the late Gallic Empire (AD 271-4). The depiction of a radiate crown alongside the stylistic rendering of the hair and beard seem, at first glance, to be virtually indistinguishable. There is however an unusual feature to Proculus’ coin that challenges the combination of the reverse legend and the personification depicted. The legend being whole on the new discovery confirms the personification to be related to ‘victory’. However there appears to be no reflection of Victoria’s most recognisable attribute (wings) on the figure itself. Yet, similarly dedicated Tetrican issues clearly depict these iconic wings alongside the legend (Fig. 6). The author however notices the remarkable similarity of Proculan imagery to Tetrican representations of Pax [Peace] (Compare Fig. 1 and 7). If such confusion is a sign of ignorance on the part of the die engraver, the rest of the coin design reflects only overt and literate skill. Consequently, iconology allows us to isolate a distinct relationship between the coinage of the Tetrican dynasty and Proculus, furthering the contention for a revisal of our current date for his revolt.

|

|

| Figure 1: Proculus reverse |

Figure 7: Tetricus Antoninianus

(AD 270-273) PAX AVG reverse

|

Intriguingly our other surviving literary reference to Proculus affirms this idea, by bizarrely also recording his revolt during the reign of the Emperor Aurelian:

“…to see to it that … Bonosus and Proculus and Firmus, who revolted under Aurelian, be not be passed over in silence.” (HA I.4)

Given this new date, earlier accounts need reappraisal in order to identify whether available evidence has been overlooked or even originally misrecorded. Given the previous association of Tetrican and Proculan coinage, the histories recounting the fall of Tetricus and the end of the Gallic Empire are of particular interest. They document how the Gallic usurper defected to Aurelian as a consequence of his inability to control his Legions’ ‘evil deeds’ (HA Life of Aurelian XXXII.3). The ambiguity of this account is problematic, as too is the implausible scenario of Tetricus simply defecting to Aurelian on account of his failure to discipline his army. Moreover, numismatic evidence clearly suggests that Tetricus had dynastic intentions for his own household, as he produced coins in the name of his son. This can only be perceived as a view to dynastic succession, thus directly contrasting with the notion of a voluntary, uncontested surrender. However, later histories allude to a mutiny within his legions at this time (Eutropius IX.13.1), and even the establishment of a rival usurper by the name of Faustinus (Aurelius Victor XXXV.4). Zonaras even adds that Aurelian succeeded in suppressing this usurper soon after receiving the surrender of Tetricus (Zonaras XII.27). Mutiny thus provides a more plausible explanation for Tetricus' surrender, as it implies that his actions were out of compulsion.

However the overall narrative is confounded by a lack of reference to the usurper “Faustinus” at any point in the Historia Augusta. Yet every indication from later sources imply that his reign lasted up to several months, easily affording him time to produce currency, especially if accounts accurately record the revolt at the Gallic mint site of Trier (Konig 1981: 181). Yet no such coins have ever appeared in the name of Faustinus and no account is provided for him in our most contemporary and complete text on third century Gallic usurpers. This history, however, strikingly resembles the picture thus far painted from a study of Proculus’ coinage. As previously argued, the idea of Proculus being the rival usurper who drove Tetricus out in AD 274 also fits significantly better with the coin iconography he displays. Such a narrative would also account for the significant rarity of Proculus’ coinage, as Aurelian was already marching on Gaul to remove Tetricus at the time of this subsequent revolt. Circumstantial evidence may therefore tempt us to entirely replace the character of Faustinus with Proculus, but neither exists on mutual exclusivity. Nevertheless, literary material still allows us to tentatively advance our knowledge on the figure of Proculus. Histories clearly indicate that a revolt occurred in Gaul at the end of Tetricus’ reign, prompting his downfall. Given the further existence of textual and iconographic data that plausibly attribute Proculus’ rebellion to this time, and to this location, Colin Popplewell’s find provides us with a new and significant opportunity to reconsider the date for this most enigmatic of usurpers.

Must it truly take one coin, in one hoard, to truly return Proculus to the annals of history?

Written by Greg Edmund, an Undergraduate Finalist at the University of Warwick, studying Ancient History. His interests are in Ancient and Medieval Numismatics.

Bibliography:

Carson, R.A.G (1965) ‘The reform of Aurelian’, Revue Numismatique, Vol.6, No. 7, pp225-235

Dessau, H (1889) ‘Uber Zeit und Personlichkeit der Scriptores Historiae Augustae’, Hermes 24, pp337-392

König, I (1981) Die gallischen Usurpatoren von Postumus bis Tetricus (München)

Morgan, L (2006) ‘Domitian the Second?’, Greece and Rome Vol 53, No.2, pp175-184

Weiser, W (1983) ‘Die Münzreform des Aurelians’, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 53, pp279-295

Figures:

Figure 1: DNW Auction (10 April 2013) Lot 694.

Figure 2: Umberto Moruzzi and Fabio Scatolini ‘The usurper Proculus and his coinage’, Coins Weekly [Accessed: 30th January 2016)

Figure 3: Aurelian pre-reform radiate: RIC 29 (http://www.wildwinds.com/coins/ric/aurelian/RIC_0029.jpg) [Accessed: 22nd February 2016]

Figure 4: Aurelian post-reform radiate (http://www.coinshome.net/) [Accessed: 22nd February 2016]

Figure 5: Dirty Old Coins (http://www.dirtyoldcoins.com/roman/id/Coins-of-Roman-Emperor-Saturninus.htm) [Accessed: 30th January 2016]

Figure 6: Wildwinds (http://www.wildwinds.com/coins/ric/tetricus_I/RIC_0141.1.jpg) [Accessed: 30th January 2016]

Figure 7: Wildwinds (http://www.wildwinds.com/coins/ric/tetricus_I/RIC_0100.jpg) [Accessed: 30th January 2016]

March 04, 2015

Spocking Fives and a Mithraic token. Currency defacement ancient and modern.

|

|

A Canadian $5 note that has been 'Spocked'

|

The death of Leonard Nimoy last week has sparked an upsurge in the Canadian practice of 'spocking' their $5 notes, using a pen or other implement to transform the portrait of their former Prime Minister, Wilfrid Laurier, into the famous Star Trek character. The particular style of the Prime Minister's portait, its large size, as well as the colour of the note (the same colour as Spock's uniform), serve to encourage this tradition (which has at least two active Facebook groups). While the alteration or defacement of currency is a crime in many societies, it is not strictly illegal in Canada, although the bank of Canada has stated that 'writing and markings on bank notes are inappropriate as they are a symbol of our country and a source of national pride'. Alterations to currencies often occur in the context of rebellion or dissatisfaction with the ruling power; defacement for fun or to honour someone is rarer.

|

| Coin altered into a token |

Ancient parallels for the practice do exist, however. During excavations of a Roman building in St. Albans in Britain (ancient Verulamium), an object (shown left) was found under Building IV (the floor dated to the second century AD). It was a silver coin (denarius) that had been altered, similar to the Canadian note above. The coin had originally been a denarius of the emperor Augustus dating from 19-4 BC, showing the portrait of the emperor on one side, and part of an ancient Roman legend on the other: Tarpeia being crushed to death by shields. What the coin originally would have looked like is shown below.

The writing on the coin (naming the moneyer responsible) has been erased, as has the obverse. The portrait of Augustus was removed, and instead a Greek legend was inscribed on the coin (RIB 2408.2): ΜΙΘΡΑC ΩΡΟΜΑCDHC ΦΡΗΝ (Mithras Oromoasdes (Ormuzd) Phren). The edge of the coin is inscribed D M (D(eo) M(ithrae)): 'To the God Mithras'. The coin was thus converted into an object in honour of the god Mithras, a god which came to Rome from the East (Ormuzd was the chief Persian god, and Phren was likely a sun god). The reason this coin in particular was chosen for conversion was again because of its imagery: myth told that Mithras was born from a rock, and so the image of Tarpeia being crushed by shields could easily be reappropriated into an image showing the deity's birth. The date of the find (well after the coin was struck) suggests that the coin may have been quite old when it was converted, though it still will have been legal currency. The process of conversion, however, would have meant that this silver coin could no longer function as money in the Roman world. The object thus represents a sacrifice of wealth: Mattingly suggests it was perhaps a token to gain admission to Mithraic worship, or to show membership of a particular level of the Mithraic cult.

|

|

Coin of Augustus showing Tarpeia (RIC 1 Augustus 299) |

Bibliography: H. Mattingly (1932). A Mithraic tessera from Verulam. Numismatic Chronicle 12: 54-7.

Images:

Canadian note: jordansawatzky via Compfight cc

Token: Wikimedia Commons.

Coin of Augustus: © Trustees of the British Museum.

November 01, 2014

Coining in Roman Britain Part 1: Before the Romans

This month the blog will run a series of posts about coinage in Britain, written by Dom Chorney. We kick the month off by looking at the coinage that existed in Britain before the Romans!

|

|

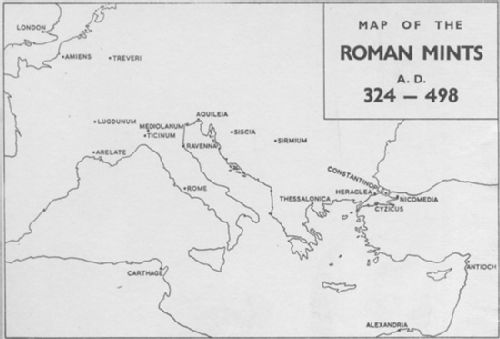

Map showing Rome's mints in the fourth century. |

The Romans didn’t just strike coins in their capitol, far from it. In fact by the 4th Century AD over a dozen official mints operated in the provinces of the empire, producing massive numbers of coins (see map). These mints tended to stem from provincial cities who struck their own coins in earlier periods of history, such as Alexandria in Egypt. Some however, were entirely new creations, in particular the mint at Londinum, modern day London. This series of posts will provide a very brief history on the subject of coin minting in Roman Britain, from the decades following the invasion in AD 43, to so called ‘decree’ of Honorius in AD 410, the date (though somewhat unreliable) believed by many to pinpoint the end of Britain as a Roman province.

Before the Romans: Celtic Coinage

|

|

Silver uninscribed stater struck in the south-west of Britain (50-20 BC). |

Despite the controversial use of the term ‘Celtic’, many scholars still refer to the coins minted in the last two centuries of Britain’s Iron Age as Celtic coins. The so called ‘tribes’ of Iron Age Britain struck coins, many deriving from gold staters produced in Greece by Philip II of Macedon, but with highly stylised designs. The iconography varies from region to region, but most Iron Age coins depict horses and stylized heads in a very abstract form. Through time, the coins of many Iron Age ‘tribes’ such as the Atrebates and the Catuvellauni become more Roman in style, indicating increasing contact with Rome. Some tribe’s coins show defiance, such as those minted in the South-West, where, rather than designs becoming more classical in nature, the coins become more abstract (see the coin pictured: coins like these are believed to indicate a strong refusal to adopt Roman style. Note the storngly stylised horse). Iron Age coins were minted in gold, silver and bronze, and are a complicated and highly theoretical topic in their own right. Mints of the Iceni (famously the tribe of the warrior queen, Boudicca) continued to produce coins in the years following the Roman invasion.

This month's coin series on Roman Britain is written by Dom Chorney, a young numismatist from Glastonbury, Somerset. He studied for his undergraduate degree at Cardiff (in archaeology), and achieved a 2:1. Dom is currently studying for an MA in Ancient Visual and Material Culture at the University of Warwick, and intends to undertake a doctorate in 2015. His main areas of interest are coin use in later Roman Britain, counterfeiting in antiquity, coins as site-finds, and the coinage of the Gallic Empire.

This month's coin series on Roman Britain is written by Dom Chorney, a young numismatist from Glastonbury, Somerset. He studied for his undergraduate degree at Cardiff (in archaeology), and achieved a 2:1. Dom is currently studying for an MA in Ancient Visual and Material Culture at the University of Warwick, and intends to undertake a doctorate in 2015. His main areas of interest are coin use in later Roman Britain, counterfeiting in antiquity, coins as site-finds, and the coinage of the Gallic Empire.

Image credits: Map from Late Roman Bronze Coinage, inside cover. Coin image from the Portable Antiquities Scheme, PAS IOW-035588.

Clare Rowan

Clare Rowan

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…