All entries for February 2021

February 24, 2021

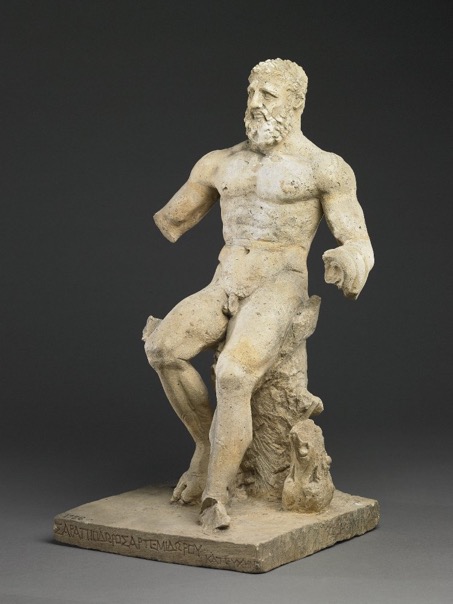

Limestone Herakles from Nineveh, by Robert Schoenell

|

Limestone statue of Herakles from Nineveh, Iraq. Height: 52.9 cm. British Museum No.1881,0701.1.Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0. |

This limestone statue of Herakles was discovered in Nineveh, Iraq in 1880 and is on display in the British Museum. Herakles is aligned facing the front of the plinth and is depicted as a bearded man, seated on a rock, using the skin of the Nemean lion as a cushion. His left hand originally held a club, the top of which is still visible on the plinth, and in his right hand he held a drinking vessel, like a skyphos or a kylix. Herakles has a ribbon wrapped around his head, with his eyes being carefully designed with an incision on the eyeball, indicating the iris and a drilled hole for the pupil. Stylistic and typological analysis of the statue make a dating to the 2nd century AD very likely.

Two Greek inscriptions are present on the plinth. The larger and more prominent of the two is on the front of the pedestal and reads:

‘ΣΑΡΑΠΙΔΟΡΟΣ ΑΡΤΕΜΙΔΩΡΟΥ ΚΑΤ’ ΕΥΚΗΝ’

‘Sarapiodorus son of Artemidorus (dedicated this) in fulfilment of a vow’

A small inscription on the left side of the plinth reads:

‘ΔΙΟΓΕΝΗΣ ΕΠΟΙΕΙ’

‘Diogenes made (this)’

Traces of red paint are visible in the cut letters of the inscription which increased the visibility of the inscription.

This statue was a votive offering to Herakles, the son of Zeus, famous for his twelve labours, who was worshiped for his outstanding strength and courage. Other Greek gods were present in the city of Nineveh as well, for example there is another limestone figure which is of Hermes on display in the National Museum of Bagdad.

Artemidorus and Diogenes are common Greek names that are not unusual in a well-connected city like Nineveh. The name Sarapiodorus has a strong connection to the god Sarapis and Ptolemaic Egypt. Nineveh was abandoned after the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 609 BC. The city was resettled under the Seleucid Empire, beginning in the 3rd century BC, and later by the Parthian Empire. It was then taken by a claimant to the Parthian throne, who was supported by Rome in 50 AD, and this opened the city to trade relations throughout the Greco-Roman world.

The statue has been identified as a copy of the Herakles Epitrapezios (Epitrapezios meaning ‘on the table’). The Epitrapezios is mentioned by Martial, in the Epigrams 9.43-44,and Statius, in the Silvae 4.6,who describe a small bronze statue in the possession of the wealthy Roman, Novius Vindex. According to Martial and Statius, the Herakles Epitrapezios was made by the famous sculptor Lysippus, for Alexander the Great (356-323 BC). It was a small table decoration, depicting the wine drinking Herakles seated on a rock, holding the club in one hand and a drinking vessel in his other. The statue accompanied Alexander on his conquest and was later in the possession of Hannibal Barka and Sulla, before finding its way into the collection of Novius Vindex.

The stylistic and typological features present in the Herakles from Nineveh are a striking example of a Roman adaptation of a Hellenistic statuary type. The frontal orientationand the incision indicating the iris are also present in 2nd century AD depictions of Herakles in Rome. The ribbon used as a headband for the Nineveh Herakles is present in depictions of Hercules on a Hadrianic relief tondo, used as a spolia for the Arch of Constantine and on a Hadrianic aureus coin.

The Nineveh Herakles was not only influenced by Roman but by local workshop traditions. The stylistic features in this statue are very similar to that present in other sculptures from the region, especially to the limestone statues from Hatra. The statue is, therefore, the result of a Roman adaptation of a popular Hellenistic statuary type, heavily influenced by the local workshop traditions of Mesopotamia.

|

This post was written by Robert Schönell who is currently participating in an Erasmus exchange and is studying Ancient Visual and Material Culture at the University of Warwick as part of his Masters studies in Classical Archaeology at Freie Universität Berlin. Robert did his undergraduate studies in Archaeology at Universität zu Köln, Cologne. Robert's research interests are sculpture and iconography, and he is especially interested in Hellenistic art and how it was copied and reinterpreted by Roman artists. |

Bibliography:

British Museum. Online at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1881-0701-1

Bartman, E. (1992) Ancient Sculptural Copies in Miniature(Columbia Studies in the Classical Tradition 19) (New York, E.J. Brill).

Invernizzi, A. (1989) ‘L'Héraclès Epitrapezios de Ninive’, in: Archaeologia iranica et orientalis: miscellanea in honorem Louis Vanden Berghe, eds L. vanden Berghe, L. de Meyer, E. Haerinck (Gent: Peeters) pp. 623-636.

Reade, J. E. (1998) ‘Greco-Parthian Nineveh’, Iraq 60, pp. 65-83.

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…