All 84 entries tagged Politics

View all 894 entries tagged Politics on Warwick Blogs | View entries tagged Politics at Technorati | There are no images tagged Politics on this blog

February 02, 2016

The KGB Gave my Book its Title

Writing about web page http://www.amazon.com/One-Will-Live-Without-Fear/dp/0817919147/

My book One Day We Will Live Without Fear: Everyday Lives Under the Soviet Police State is published today in the US. It will be available in Europe from February 29. This is the story behind the title of the last chapter of my book, which I also used as the title of the book as a whole.

It’s 1958. David is chatting to his friend. Their subject is David’s dream, which is to emigrate. He’s a Jew, living in Vilnius, the capital of Soviet Lithuania. He was once a Polish citizen, born on territory that was absorbed by the Soviet Union in 1939 when Stalin and Hitler split Poland between them. Suddenly, David was a Soviet citizen. In World War II he fought in the Red Army. After the war he settled in Vilnius, got married, and made a family.

In the 1950s there was a short window when the Soviet authorities allowed people like David, born Polish, to leave for Poland if they wished. His younger sister, Leila, left for Poland the previous year, and from there she was able to travel on to Israel. David did not go with her, but now he regrets that he stayed behind. He would like to follow her, but he finds that he is trapped. Whether he left it too late, or for some other reason, the government will not let him go.

David tells his friend that he has become afraid of even asking about permission to leave.

It could turn out that you put your papers in to OVIR [the Visa and Registration Department] and they give them back to you, and then you get a ticket to Siberia, or they can put you in jail.

David has come to a decision. There's no point dreaming about leaving, he tells his friend. He has concluded it's dangerous even to think about it. He realizes he is going nowhere. He and his family will stay at home. But then he comes back to another thought, perhaps even more dangerous, that he cannot help but voice:

We’ll stay in Vilnius and we'll live in the hope that he [one of the Soviet leaders of the time, not named] and generally this whole system will smash their heads in, and maybe we will live here freely and without fear.

After that, David’s friend went home and made a note of the words David had used. In due course he passed the note to his handling officer, because this friend, unknown to David, was a KGB informer. The note ended up in the files of the Soviet Lithuania KGB, where I came across it more than half a century later.

The KGB handler thought David's remarks were pretty interesting. At the end of the report he summed up:

Report: Information on David received for the first time.

Assignment: The source [David's friend] should establish a relationship of trust with David and clarify his contacts. Investigate his political inclinations and way of life.

Actions: Identify David and verify his records.

Few people who lived in Soviet times ever imagined those times would come to an end. David was one of the few.

What was life in the Soviet Union really like? Through a series of true stories, One Day We Will Live Without Fear describes what people's day-to-day life was like under the regime of the Soviet police state. Drawing on events from the 1930s through the 1970s, Mark Harrison shows how, by accident or design, people became entangled in the workings of Soviet rule. The author outlines the seven principles on which that police state operated during its history, from the Bolshevik revolution of 1917 to the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, and illustrates them throughout the book. Well-known people appear in the stories, but the central characters are those who will have been remembered only within their families: a budding artist, an engineer, a pensioner, a government office worker, a teacher, a group of tourists. Those tales, based on historical records, shine a light on the many tragic, funny, and bizarre aspects of Soviet life

One Day We Will Live Without Fear: Everyday Lives Under the Soviet Police State, by Mark Harrison, is published on 2 February 2016 by the Hoover Press in Stanford, California. Order it today from Amazon US or pre-order it from Amazon UK.

January 01, 2016

Supplying Hatred

Writing about web page https://www.facebook.com/groups/2358386395/

It all began with this:

The image originated on a facebook page called “I hate David Cameron.” Then it was shared around until one of my friends liked it. So, on Christmas Day in the evening, it appeared on my facebook home page.

Things like this present me with a social dilemma. I want to keep facebook for friends and family and so I try to stay off politics. However, others don’t. When something like this pops up, I want to respond. Mostly I don’t, but I can’t help thinking to myself that nasty things take over the internet when nobody speaks up against them. So, from time to time I make an exception. This was one of those times. I waited until the original posting had some likes and approving comments and then I stuck my oar in.

Here’s how it went. The characters other than me are F (my friend), FOF (friend of my friend), and other random people whom I’ve labelled X, Y, and so on.

F and 11 others like this.

Comments

X: I disagree. He is not smeling of roses by any means, to put my views politely, but Thatcher was even worse! (26 December at 13:21)

FOF: She's where it all started in the UK. (26 December at 13:40)

X: For our generation, for sure. (26 December at 13:41)

FOF: And RayGun in the USA. (26 December at 14:04)

Y: He does have one of those faces you'd like to slap. Over and over and over and... (26 December at 14:08)

Y: Cameron is still Thatcher in drag (26 December at 14:09)

Z: Thatcher / Cameron. Its a close-run thing. But be prepared for PM Osborne. We have seen nothing yet, I'm afraid (26 December at 15:40)

Me: A shame that the hate speech factory could not observe even a Christmas truce. (26 December at 17:43)

FOF: I don't think that Cameron et al stop for Christmas. (27 December at 02:25)

Me: Yes, but that's not the point. The point is that it shouldn't be normal to spread hatred of anyone for what they are, for their colour or religion or politics or whatever. At Christmas or any other time. (27 December at 12:21)

Z: It should not be normal to blame the previous government for everything. Soon the floods will be Labour's fault, to the Tories. (28 December at 20:14)

FOF: Perhaps I'm not a Christian. (29 December at 13:08)

FOF: or perhaps I am. Would Christ have stopped admonishing wrongdoers just because it was a particular date ... a particular time of year? ... 'Oh. I'd better not throw the moneylenders out of the temple today because it's Channukah.'? (29 December at 13:12)

Me: That's not the point (again). Criticize all you want, but spreading personal hatred of the people you disagree with is wrong. You don't have to be a Christian to know wrong from right, any time of the year. (29 December at 15:29)

FOF: Sorry Mark, no, the statement is not a statement of hate. It is a statement regarding David Cameron and an opinion about him which is only challengeable on grounds of accuracy. The timing of the statement is irrelevant, Christmas, Holi, Purim....etc. (29 December at 15:45)

Me: Now you're being disingenuous. If you were just trying to educate us,, you'd share your sources (and you'd explain how we know how many people hated the prime minister before opinion surveys existed). That's not how it is. You have a partisan goal, which is to push the idea that Cameron is uniquely hated and the idea that political hatred is OK. (29 December at 20:45)

That’s where the conversation stands today.

Just to be clear on a couple of points: First, I’ve got no objection to political commentary, to discussing a politician’s character, or to strong feelings. It’s at the spreading of hatred that I draw the line. I draw it there for both moral and philosophical reasons. The expression of hatred against a person or a group amounts to expelling them from our moral community. It's a step on the road to collective violence.

Hate speech has interested me since I read Ed Glaser’s classic Political economy of hatred in the QJE (2005). Glaser describes a market for hatred. In the market there is a demand and a supply. The demand is stimulated when a society experiences a collective setback and demands explanation. The merchants of hatred are those that identify scapegoats and offer them as objects of hatred. The story often has a bad ending.

One of the interesting things about social media is that it becomes fairly easy to trace the supply chain back through the intermediaries to the originators of the supply of hatred.

Of course there are much worse examples than this one, especially where the victim does not have the social defences of a David Cameron. I picked this one only because it came up between friends.

And second, Robert Walpole was prime minister in the eighteenth century. But what’s a couple of centuries among friends?

A happy, hate-free New Year to my readers.

November 02, 2015

The Great War: the Value of Remembering it As it Really Was

Writing about web page http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3298895/Jeremy-Corbyn-comes-fire-denouncing-shedloads-money-spent-World-War-One-commemorations.html

In the spring of 2013, the British government was considering how the nation should remember the centenary of the Great War. At that time Jeremy Corbyn made some remarks on the subject, and in April the Communist Party uploaded them to Youtube. His words would no doubt have lingered in obscurity, were it not that in September this year the same Jeremy Corbyn was elected leader of Britain's Labour Party. This weekend his remarks of more than two years ago were brought under critical scrutiny. What attracted the ire of the Sunday columnists was the following words:

Keir Hardie ... was a great opponent of the first world war and next year the government is apparenlty proposing to spend shedloads of money commemorating the first world war. I'm not quite sure what there is to commemorate other than the mass slaughter of millions of young men and women, mainly men, on the western front and all the other places.

As an economic historian I was more interested in what came next:

And it was a war of the declining empires, and anyone who's read or even dipped into Hobson's great work of the early part of the twentieth century, written post-world war, that presaged the whole first world war as a war between monopolies fighting it out for markets and that's essentially what the first world war was.

My notes. "The declining empires": I'm not sure what that can mean, for in 1914 the major empires were surely at their highest moment. "Hobson's great work of the early part of the twentieth century." This is most likely a reference to J. A. Hobson work on "imperialism." Hobson (1902) argued that the capitalist industrial economies of the time suffered from underconsumption, because the big companies were raising productivity while pushing down wages. As a result, there was not enough purchasing power to buy all the output, which was accumulating as surplus capital. Faced with too much capital, Hobson argued, the capitalists solved the problem by exporting it to poorer countries. Having done that, they needed to protect their investments by bringing the poorer countries under colonial administration. So, this was a a theory of imperialism. Being published in 1902, Hobson's book was not "written post-world war" because the world war was yet to come. And it did not presage the coming war "as a war between monopolies fighting it out for markets"; that idea came along later, when the war was already in progress, and belongs to Lenin (1916). While Hobson did not predict the Great War, he did draw a clear link from imperialism to nationalism, and he opposed the war when it came.

How does the Hobson-Lenin view of the Great War stand up today? Not well. Here are two problems:

Problem #1. The surplus of capital does not explain imperialism. In the words of Gareth Austin (2014: 309):

the major outflows of capital from the leading imperial powers, Britain and France, went not to their new colonies but to countries which were either the more autonomous of their existing colonies (such as Australia) or were former colonies (the United States), former colonies of another European country (as with Argentina), or had never been colonized (Russia). Decisively, several of the expansionist imperial powers of the period were themselves net importers of capital: the United States, Japan, Portugal, and Italy.

Problem #2. The protection of business interests abroad does not explain the outbreak of the Great War. Richard Hamilton and Holger Herwig (2004) reviewed the evidence, country by country. In every case, including specifically Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, they found that the business constituency was excluded from the decisions that led to war. Had the business leaders been consulted, they would have opposed war. (This would also have been true in Russia, a case that Hamilton and Herwig do not consider.) They conclude (p. 247):

Economic leaders were not present in decision-making circles in July 1914. And, just as important, their urgent demands to avoid war were given no serious attention. It is an unexpected lesson because many intellectuals give much emphasis to the power of big business. The logic is easy: industrialists and bankers have immense resources; anxious and deferential politicians, supposedly, must respond to their demands. But the realities were quite different. At one point a German banker, Arthur von Gwinner, “had the audacity to point out Germany’s dire financial straits” to Wilhelm II. The monarch’s reply: “That makes no difference to me.”

In remembering the Great War, we should be careful to remember it as it really was. War did not break out in 1914, as Jeremy Corbyn seems to think, because of a money-making war machine, or because commercial interests were manipulating politics behind the scenes.

The Great War broke out because secretive, unaccountable rulers in Vienna, Berlin, and St Petersburg decided on it (I wrote about this in more detail in Harrison 2014). They feared the consequences but decided on war regardless because they believed the national interest would be better served by risking it in aggression than by remaining at peace. They believed this based on a nationalist, militarist, and aristocratic view of the national interest, in which profit and commercial advantage played no role. They decided on war in July 1914, and not in any previous crisis, because in previous crises they had been divided. They came together in July 1914 because this was a moment when Anglo-French deterrence failed, and this reduced their fear of the consequences of aggression below some critical threshold.

Thus two deeper causes lay behind the Great War. One was the ability of autocratic rulers to plan aggressive war in secret, ignoring public opinion, or taking it into account only to manipulate it. The other was the failure of the democracies to deter the aggressors. These lessons are still of value today. But to value such lessons you first need a desire to learn about what actually happened. And a political leader who bases his entire understanding of the Great War on a book published in 1902 seems to have missed that desire to learn.

References

- Austin, Gareth. 2014. "Capitalism and the Colonies." In The Cambridge History of Capitalism, vol. 2: 301-347. Edited by Larry Neal and Jeffrey G. Williamson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hamilton, Richard F., and Holger H. Herwig. 2004. "On the Origins of the Catastrophe." In Decisions for war, 1914–1917, pp 225–252. Edited by Hamilton and Herwig. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Harrison, Mark. 2014. "Myths of the Great War." CAGE Working Paper no. 188. University of Warwick, Department of Economics. Available at http://warwick.ac.uk/cage/manage/publications/188-2014_harrison.pdf

- Hobson, J. A. 1902. Imperialism: A Study. New York. Available online.

- Lenin, V. I. 1916. Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism. Petrograd. Available online.

July 06, 2015

Russia's Leaders: Thieves versus Policemen

Writing about web page http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-33290421

Yevgeniy Primakov, who has died aged 85, was briefly Russia's prime minister under President Boris Yeltsin. Primakov's early career followed a classic Soviet trajectory: a specialist and postgraduate researcher in foreign afffairs, he became a foreign correspondent, a collaborator with the KGB's foreign service, and an Academician. After the conservatives' failed coup in 1991 he became the last first deputy head of the KGB and then the first head of the SVR, Russia's new foreign intelligence service.

I was in Moscow in September 1998 when President Yeltsin appointed Primakov prime minister. Primakov took the place of Viktor Chernomyrdin, the founder of Gazprom, who presided over a notoriously corrupt administration. In the company of friends I asked:

Well, what would you rather: to be governed by a thief or a policeman?

Without pausing for thought my friends responded with one voice:

A thief!

Why? (I asked).

When it's a thief, at least you know what they're up to.

Primakov did not last long in office. A few months later he was succeeded as prime minister by Vladimir Putin. A few months after that, the same Putin succeeded Yeltsin as President of Russia.

As time passed I often remembered this conversation, especially when I had to think about corruption and the rule of law.

Eventually I decided that my initial question was probably based on an error. In law-governed societies, the distinction between thieves and policemen is clear: thieves break the law and policemen enforce it. But there are lots of places around the world, including Russia, where the rule of law does not fully apply. In such situations the lines between thief and policeman become blurred to the point where it's hard to tell them apart.

When personal safety is at risk and property rights are not secure, thieves take on some of the functions of policemen because they need to protect their ill-gotten gains from robbery by others, or they find they can augment their gains by selling "protection" to others. And policemen become thieves by stealing from ordinary citizens while selling exemption from the law to their political masters and criminal friends.

Russia today is a mixed picture. I'm sure there are some honest policemen and honest politicians. But for such people it will be a struggle to survive and a danger to rise too high.

May 08, 2015

Violent Borders: Will There be Another Great War?

Writing about web page http://daily.rbc.ru/opinions/politics/08/05/2015/554c800c9a79473a8f5d6ee2

This column first appeared (in Russian) in the opinion section of RBC-TV, a Russian business television channel, on 8 May 2015.

This week we remember the worst war in history. But we remember the war differently. Russians remember the war that began in June 1941 when Germany attacked the Soviet Union. Most other Europeans (including Poles and many Ukrainians) remember the war that began in September 1939 when Germany and the Soviet Union joined to destroy Poland. The Americans remember the war that began in December 1941 with Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. The Chinese remember the onset of Japan’s all-out war at the Marco Polo Bridge in 1937.

Many separate wars came together to make World War II. All of them were fought over territory. These wars began because various rulers did not accept the borders that existed and they did not accept the existence of the independent states on their borders. They used violence to change borders and destroy neighbouring states. When they did this, they justified their violence based on the memory of past wars and grandiose concepts of national unification and international justice.

Will there be another Great War? We should hope not, because another Great War would be fought with nuclear weapons and would kill tens or hundreds of millions of people.

A reason to be hopeful is that war is never unavoidable. War is a choice made by people, not a result of impersonal forces that we cannot control. Most differences between countries can be negotiated without fighting. However, claims on territory and threats to national survival are the most difficult demands to negotiate, and this is why they easily lead to violence.

In today’s world there are several places where border conflicts could provide the spark for a wider war. Most obvious is the Middle Eastern and North African region. Small wars have raged there in the recent past and several are raging there now. Israel’s existence has been contested since 1948. The borders of Libya, Iraq, and Syria are being redrawn by force. Access to nuclear weapons is currently restricted to Israel, but could spread and probably is spreading as I write.

But the whole of the Middle East and North Africa includes only 350 million people. More than twice as many people, 750 million, live in Europe. There is war in Europe because Russia has unilaterally seized the territory of Crimea and is fuelling conflict in Eastern Ukraine. The effects have spread beyond Ukraine. Russian actions have raised tension with all the bordering states that have Russian speaking minorities, including some that are NATO members. Russia is rearming and mobilizing its military forces. Russian administration spokesmen speak freely of nuclear alerts and nuclear threats.

Looking to the future, we should all worry about East Asia, home to 1.5 billion people. There China is building national power through economic growth and rearmament. China is also redrawing the map of the South China Sea, and this is leading to border disputes with Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei and Indonesia. Given China’s size and Japan’s low military profile, the only counterweight to Chinese expansion is the U.S. Navy, and this increases the scope for a future nuclear confrontation. While Japan keeps a low profile is low, its relations with China are poisoned by nationalist reinterpretations of World War II on both sides.

In all of these regions there are territorial claims and disputed borders, with the potential to draw in nuclear powers on both sides of the conflict.

Can we learn from our past wars so as to avoid the future wars that we fear? Yes. The first lesson of a thousand years of European history is the value of stable borders. Eurasia stretches for ten thousand miles without natural frontiers. When states formed in Eurasia they had no clear territorial limits, and they fought each other continuously for territory.

The idea of sovereign states that respect others’ borders and leave each other in peace is usually identified with the Peace of Westphalia (1648). But in 1648 this idea was only a theory. The practice of mutually assured borders is much more recent. The European Union is a practical embodiment of mutually assured borders; this is reflected in the fact that France and Germany no longer fight each other and the smaller states around them also live in peace.

Russia has always been at the focus of European wars. The Correlates of War dataset on Militarized Interstate Disputes counts 3,168 conflicts from 1870 to 2001 that involved displays or uses of force among pairs of countries. The same dataset also registers the country that originated each disputes. Over 131 years Russia (the USSR from 1917 to 1991) originated 219 disputes, more than any other country. Note that this is not about capitalism versus communism; Russia's leading position was the same both before and after the Revolution. The United States came only in second place, initiating 161 conflicts. Other leading contenders were China (third with 151), the UK (fourth with 119), Iran (fifth with 112), and Germany (sixth with 102).

How did Russia come to occupy this leading position? Russia is immense, and size predisposes a country to throw its weight around. Russia has a long border with many neighbours, giving many opportunities for conflicts to arise. And authoritarian states are less restrained than democracies in deciding over war and peace. Russia's political system has always been authoritarian, except for a few years before and after the end of communism, when Russia's borders were able to change peacefully.

Russians have suffered terribly from the territorial disputes of past centuries. When the Soviet Union broke up, Russia's new borders were drawn for the most part peacefully. This was a tremendously hopeful omen for Russia's future. Particularly important were the assurances given to Ukraine in 1994: Ukraine gave up its nuclear weapons and in return the US, UK, and Russia guaranteed Ukraine's borders. The promise was that Europe would no longer suffer from territorial wars. Instead, Europe’s borders could be used for peaceful trade and tourism.

Russia, of all countries, has most to lose from returning Europe to the poisoned era of conflicted borders and perpetual insecurity. The best way for Russians to commemorate the end of World War II is to return to the rule of law for resolving its dispute with Ukraine. In questions of borders and territorial claims the rule of law should have priority over all other considerations, including ethnic solidarity, the rights of self-determination, and the political flavour of this or that government. That is the most fitting tribute to the memory of the tens of millions of war dead.

March 23, 2015

Group, then Threaten: How Bad Ideas Move Millions

Writing about web page http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2014.0719

I've been thinking: What is it that enables a bad idea suddenly to spread across millions of people? Here are some of the things I have in mind:

- In France the National Front is reported as leading all other parties in current opinion polls, having won barely 10 percent of the vote in the 2007 presidential election.

- In January's general election, nearly 40 percent of Greek voters supported Syriza, compared wtih fewer than 5 percent as recently as 2009.

- Since narrowly rejecting indendence in last year's referendum, Scotland's voters have rallied to the Scottish National Party, support for which is now reported at over than 40 percent compared with less than 20 percent at the last general election.

- Most spectacularly, more than 80 per cent of Russians are regularly reported as thinking Vladimir Putin is doing a great job as their president, compared with around 60 percent two years ago.

I am hardly the first to ask this question. There is plenty of research (e.g. de Bromhead et al. 2013) on the economic conditions that foster political extremism, for example. But how do we get from economic conditions to wrong persuasion, exactly? There is the famous Goebbels quote about the "big lie," which is fine as far as it goes but always makes me think: surely there's more to it than this?

If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it. The lie can be maintained only for such time as the State can shield the people from the political, economic and/or military consequences of the lie. It thus becomes vitally important for the State to use all of its powers to repress dissent, for the truth is the mortal enemy of the lie, and thus by extension, the truth is the greatest enemy of the State.

But it can't be true of all lies. Don't some lies work better than others? What is it that defines the ones that work? My best answer so far to this question is an analogy, which I know is less than proof. But it's a thought-provoking analogy; see what you think.

Last year some behavioural scientists (Strõmbom et al. 2014) finally explained how to herd sheep. There is a sheepdog, instructed by a shepherd, that does the running around. It turns out that there are just two stages. First, the dog must gather the sheep in a single compact group. Once that is done, the second step is to threaten the group from one side; as a group, the sheep will move away from the threat in the opposite direction. That's all there is to it.

The reason why the first step must come first is also of interest: If the dog threatens the sheep without first gathering them in a group, they will scatter in all directions, and that's not what the shepherd wants.

Anyway, there's the answer: Group, then threaten.

People are not sheep, and this is only an analogy. Nonetheless you probably already worked out how I would read this. The shepherds are the political leaders. The dogs that run around for them are the campaign managers and activists. The human equivalent of gathering sheep in a group is to polarize people around an identity that defines an in-group and an out-group. So Scots (as opposed to the English), Greeks (as opposed to the Germans), Russian speakers (as opposed to the rest). Group them, then threaten them, and they will move.

To see how the threat sets the group in motion we need one more thing, an insight from Ed Glaeser. Glaeser (2005) wanted to explain the conditions under which politicians become merchants of hate. He began with a community that has suffered some kind of collective setback. When that happens, people demand an explanation: Who has done this to us? "Us" means the in-group. Political entrepreneurs, he argued, will compete to supply satisfying stories. Often the most satisfying account is one that blames the in-group's misfortune on the alleged past crimes of some out-group: the English, the bankers, the Muslims, the Jews, or the West.

Not only past crimes, however; Glaeser uses the phrase "past and future crimes." In other words, he maintains, politicians often transform these stories into powerful threats by giving them a predictive slant: This is what they, the enemy, have done to us in the past and this is what they will do again if we don't mobilize to stop them first.

Remember: Group, then threaten. The result is mobilization.

References

- de Bromhead, Alan, Barry Eichengreen, and Kevin H. O'Rourke. 2013. Political Extremism in the 1920s and 1930s: Do German Lessons Generalize? Journal of Economic History 73/2, pp. 371-406. URL https://ideas.repec.org/a/cup/jechis/v73y2013i02p371-406_00.html.

- Glaeser, Edward L. 2005. The Political Economy of Hatred. Quarterly Journal of Economics 120/1, pp. 45-86. URL: https://ideas.repec.org/a/tpr/qjecon/v120y2005i1p45-86.html

- Strömbom, Daniel. Richard P. Mann, Alan M. Wilson, Stephen Hailes, A. Jennifer Morton, David J. T. Sumpter, and Andrew J. King. 2014. Solving the shepherding problem: heuristics for herding autonomous, interacting agents. J. R. Soc. Interface 11: 20140719. URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2014.0719.

February 27, 2015

Russia Under Sanctions: It's Not Working

Writing about web page http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/92c75076-b606-11e4-a577-00144feab7de.html

On the evening of Tuesday 24 February I joined a panel discussion on "Russia Now," organized by Warwick Arts Centre's Mead Gallery. My fellow panellists were Peter Ferdinand (Politics and International Studies) and Christoph Mick and Christopher Read (History). The discussion was chaired by Mead Gallery director Sarah Shalgosky, whom I thank for the invitation. Here's what I said, roughly speaking.

Sanctions in history

The Russian economy is subject to Western sanctions. These sanctions are of two kinds. There are "smart" sanctions that aim to limit the international travel and transactions of named persons and corporations. There are also broader sanctions that aim to limit the international trade and borrowing of Russia’s financial, energy, and defence sectors.

In history, advocates of economic sanctions against an adversary have usually claimed two advantages for them. One claimed advantage is speed of action: It has often been predicted that economic sanctions will quickly "starve out" an adversary (metaphorically or literally). The other claimed advantage is cost: By attacking the adversary’s economy we can achieve our goals without the heavy casualties to our own side that would result from a military confrontation.

Are these claims justified by experience? Based on the experience of modern warfare and economic sanctions from the Napoleonic Wars through the U.S. Civil War and the two World Wars of the twentieth century to the Cold War, Rhodesia, South Africa, and Cuba, the answer has typically been: "No."

How do sanctions work?

The effects of sanctions on national power have generally been slower and smaller than expected. First, they attack national power indirectly, through the economy, and the economy provides a very complicated and uncertain transmission mechanism. If a country is refused access to something for which it appears to have a vital need, such as oil or food, it generally turns out that there are plenty of alternatives and ways around; nothing is as essential as it seems at first sight. Secondly, external measures will be met by counter-measures. In a country that is blockaded or sanctioned, soldiers will look for ways to use military strength to break ouit and so offset economic weakness. Suffering hardship and feeling unfairly victimized, civilians will become more willing to tighten their belts and fight on.

It would be wrong to go to the other extreme and conclude that sanctions achieve nothing. What have sanctions actually achieved in historical experience? Sanctions do raise the cost of producing national power. They do so gradually, so that immediate effects may not be perceptible. Nonetheless they impose costs on the adversary, and eventually these costs will tell. It is hard to show, however, that sanctions have ever had a decisive effect on their own; at best, they have been shown to have their effect in combination with other factors, such as military force. In those cases, sanctions were a complement to military power, not a substitute or alternative.

Russia: How are Western sanctions supposed to work?

The purpose of Western sanctions is clear: It is to change President Putin’s behaviour, making him more cautious and more accommodating to the demands of Western powers.

What is the mechanism that is supposed to bring this about? Western observers generally see that President Putin's political base is built on the use of energy profits to buy political support. Russia's energy sector, much of it state-owned, has provided major revenues to the Russian government budget. The Russian government uses these revenues to buy support, partly by paying off key persons, partly by subsidizing employment in Russia's inefficient, uncompetitive domestic industries. The result is that many people feel obligated to Putin's regime because without it they would lose their privilege or position in society.

In that context, sanctions have been designed to target those industries and persons that supply resources to the government and those that depend on the government for financial support. By doing so, they aim to deprive President Putin of the resources he needs to retain loyalty.

How have sanctions actually worked? In Russia, real output is falling and inflation is rising. It is important to bear in mind, however, that in recent months sanctions have been only one of three external sources of pressure on the Russian economy.

Three pressures on Russia's economy

Three factors have been at work: sanctions, confidence in the ruble, and energy prices. These factors should be thought of as semi-independent: there are obvious connections among them, but in each case the agency is different.

- Sanctions. Before the crisis over Crimea, Russian corporations had approximately $650 billion of short-term, low-interest debt denominated in foreign currency. International lenders have reluctant to lend to Russia long term because Russia's lack of protection of property rights leaves them uncertain about the security of their loans. Because this debt is short term, it requires regular refinancing. Russian firms, including organizations and sectors that have not been directly targeted by sanctions, are now unable to borrow abroad. Struggling to cover their credit needs, they have turned to the Russian government to make emergency loans or bail them out.

- Confidence in the ruble. As lenders have lost confidence in Russia, capital flight has increased. The ruble has lost half its external value in the last year, and this has doubled the real burden of private foreign currency debts of Russian corporations and also wealthy families with housing debts in euros or dollars. This has intensified private sector pressure on the government for bail-outs.

- Oil prices. The dollar price of oil has halved since this time last year, slashing Russia's energy revenues and plunging the state budget into deficit.

These three pressures all point in the same direction and complement each other. Their cumulative effect is to be seen in the deteriorating outlook for the economy as a whole and for public finance. The government has lost important revenues while spending pressures have multiplied. Arguably, therefore, sanctions have "worked," because they have squeezed the capacity of the Russian administration to satisfy the expectations of its supporters.

A learning opportunity

From a social-science perspective, we should think of this moment as a learning opportunity: How the Russian administration responds in these circumstances should reveal its type.

To benchmark the Russian response today, consider how two Soviet leaders responded to closely similar situations in the past.

- One benchmark is offered by Mikhail Gorbachev in 1985. By the mid-1980s the global energy market had reached a situation not far removed from that of today. A decade of high oil prices was being brought to an end by new non-OPEC suppliers. This put the Soviet economy under a severe squeeze. Faced with this squeeze, Mikhail Gorbachev chose policies of demilitarization and relaxation abroad and at home.

- Another benchmark is offered by Joseph Stalin in 1930. If anything, the predicament of the Soviet economy in 1930 was even closer to its situation today. Soviet exports were faced with collapsing prices as the world economy entered the Great Depression. The Soviet economy also had considerable short-term debts that suddenly could not be rolled over because international lending dried up. In response, Stalin demanded "the first five year plan in four years!" This involved accelerated mobilization and sacrifice, and ended in the famine deaths of millions of his own citizens (many of them in Ukraine).

These examples illustrate the alternative responses of a ruler under external pressure. When it becomes harder to buy loyalty the ruler can respond like Gorbachev, by moderating demands on supporters; or like Stalin, by cracking the whip over them. In 2015, faced with economic sanctions, falling oil prices, and a falling ruble, which choice has President Putin made? His words and deeds both deserve attention.

- Before sanctions, President Putin's words were of a Russia encircled by enemies and penetrated by foreign agents. His policies involved accelerated rearmament and frozen conflicts with Moldova and Georgia, capped by the annexation of Crimea.

- How did things change after Western sanctions were imposed? Putin's rhetoric shifted up a notch with talk of national traitors and a "fifth column" of enemies within. His economists began to discuss ways to shift from a market economy to a "mobilization economy." His foreign policy spokesmen incited tensions in the Baltic region and made nuclear threats against the West. The Russian military embarked on continuous large-scale exercises and increased the frequency of testing NATO defences in the Baltic and the North Sea. Russian forces and heavy weapons were infiltrated into Eastern Ukraine.

The lesson for social science is that under external economic pressure President Putin has revealed his type: He is a power-building authoritarian ruler.

It isn't working

From a policy perspective, the effect of sanctions on the Russian economy is only the tactical outcome of sanctions. Their strategic purpose is to change Russia's behaviour for the better, and that is the only true test of whether they have worked. The lesson for policy is that, despite sanctions, President Putin remains prepared to take risks with peace and to commit aggression. Sanctions are not changing his behaviour.

Now we know this, what should we conclude? A clear implication is that things could get worse. Some worry (or threaten) that, if the pressure on him grows, President Putin might became more confrontational and take additional risks rather than back down and look for compromise. It has also been suggested that, if unseated, Putin might be replaced by someone worse -- a role for which there are several candidates.

Why isn't it working?

This leads to me to a sombre conclusion. It's not a conclusion that I much like; I have thought about it a lot and I wish I could see another way out of the situation. To sum it up, I'll quote in full a letter that I wrote to the Financial Times recently in response to an article by Gideon Rachman ("Russian hearts, minds, and refrigerators," February 16). My letter appeared on 19 February:

Gideon Rachman ... writes : “Rather than engage the Putin government where it is relatively strong, on the battlefield, it makes more sense to hit Russia at its weak point: the economy.” But this neglects the incentives that arise from the time factor.

If the West plays to its strength, which is economic, President Putin will play to Russia’s strength, which is military. But the action of Western financial and trade measures is slow and cannot be accelerated. Meanwhile, Russia can accelerate its military action at will.

In playing the sanctions card while neglecting defence, the West is encouraging President Putin to raise the tempo on the battlefield and change realities quickly and irrevocably through warfare, before the Russian economy can be weakened further.

For the West, therefore, economic sanctions are not an alternative to a military confrontation that is already under way. To avoid disaster, the West must support financial and trade measures with a credible defence.

December 22, 2014

The Meaning of Christmas, 1914: When Peace Broke Out

Writing about web page http://www.wsj.com/articles/the-spirit-of-the-1914-christmas-truce-1419006906

At Christmas 1914 up to 100,000 troops on the Western front took part in unofficial truces. They left the opposing trenches and exchanged greetings, cigarettes, food, and drink. Most famously, some of them may have played football.

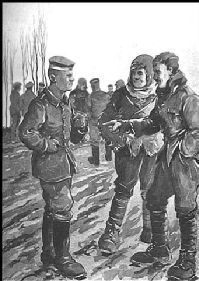

The moment was captured by Bruce Bairnsfather (1917); thanks to Major and Mrs Holt, Bairnsfather's biographers, for permission to reproduce this image.

The Christmas truce of 1915 is often considered to be something rather unique. In fact, as the sociologist Tony Ashworth (1980) showed, it was a special case of a wider pattern. The Christmas truce was special because there was open fraternization. The wider phenomenon was simply a tendency for the soldiers on both sides, left to themselves, to bring down the level of conflict and hostility. They did this spontaneously, without calculation, using coded signals that did not need to be translated into words or confirmed by shaking hands. The signals were the dawn volley, aimed far above the enemy's heads, or the tea-time shell that always fell wide of the mark. These were signals of a lack of hostility that the receiving soldiers could easily come to recognize, predict, and reciprocate.

In this way the soldiers on each side would learn to collude with the enemy to avoid direct clashes and minimize the danger on both sides.

Ashworth called this pattern of behaviour "live-and-let-live." Live-and-let-live was observed in all periods of the war; the Christmas truce of 1914 was unusual only in that the men's desire to avoid outright hostilities was expressed openly. But it did not need to be expressed openly to persist. Live-and-let-live could develop without any explicit communication.

The crucial condition for live-and-let-live to develop was that the men were left alone for long enough to learn its language. But military commanders learned not to leave their men alone. They learned to intervene in the game of live-and-let-live and to disrupt it by teaching their men another language, the language of hostility. In between the great offensives, the soldiers learned the language of hostility in night raids. Night raiding involved crossing to the enemy trenches under cover of darkness to surprise, kill, destroy, steal, and kidnap. Night raids were dangerous, caused losses to both sides, stimulated the desire for revenge, and engendered persistent mutual hostility.

For all the same reasons, night raids were universally detested. The British and French officers approached this problem differently. The result was a kind of field experiment in different types of motivation. The French officers asked for volunteers and used positive incentives and rewards to encourage participation. In contrast, the British officers used direct orders that required all troops to take part in rotation.

The result, according to Ashworth, was that in the French army night raiding was generally regarded as exceptional service, demanding special recognition. In the British army, on the other hand, night raiding was seen as one of the regular duties of front line service. Because of this, the British were able to carry out the policy of night raiding at a higher level than the French in 1915 and subsequent years. In the British sector there was more hostility and live-and-let-live was cut off at the root. Armed with superior motivation, the British troops then showed greater commitment in both minor and major offensives.

In contrast, Ashworth argued, French morale declined to the point where, in 1917, faced with orders to go once more into battle, half the regiments in the French army experienced mutinies. Ashworth supported his argument with a striking fact: On the German side of the French sector in 1917 there was no awareness that the troops in the opposing trenches were refusing orders to attack. This can only mean that the German soldiers had become completely habituated to the French passivity and so saw no change in the behaviour of the French soldiers.

Could the Christmas truce have ended the war before it had barely begun? Was it a lost chance to avert the premature deaths of tens of millions of people? It is a tempting thought, but we are bound to conclude that there are several reasons why this could not have been the outcome.

Live-and-let-live was surely facilitated by trench warfare, when large numbers of soldiers faced each other for long periods across static lines, and could learn to reciprocate each others' behaviour. But static warfare was temporary. The war began with movement, and by the time it ended the ability of the troops to move had been restored by new weapons and technologies.

If the war had ended on the Western front in December 1914, it would have left Germany in possession of a large slide of eastern France. The French leaders would surely have resumed the war at some point for this reason.

If the war was not quickly restarted in the West, Germany's leaders had another war to fight in the East, a war on Russia that in their strategic vision was more vital to Germany's interests than the war on France. The Germans would surely have exploited a truce in the West to pursued the war in the East with redoubled energy.

In fact the political leaders and military commanders were able quickly to overcome the natural tendency to live and let live and so return to the war. They were learning rapidly how to mobilize their nations around national identity, how to use their economies to deploy and arm millions of young men for combat, and how to organize those young men into fighting organizations that would attack and defend in together in large-scale operations, regardless of victory and defeat.

The Christmas truce of 1914 is testimony to the intense desire of most young men not to die and not to kill. It is also evidence of the growing aversion to extreme violence that writers such as Steven Pinker (2011) have identified over thousands of years of human history. It reproaches the rulers of 1914 that condemned Europe to thirty years of mass warfare. But it did not and could not overcome the political calculations that led to war at that time.

In 2014 the Kremlin's political calculations have led to war in Ukraine. Russian leaders seem to have no qualms when they threaten to widen the use of force in Europe by means of rapid rearmament, large-scale miltary exercises, and continuous probing of NATO air and sea defences, and by talking up the use of nuclear weapons.

From one end of Europe to the other today there is ample evidence of the innate desire of ordinary people to live and let live. But live-and-let-live does not offer a solution to the problem of authoritarian rulers that make their war plans in secret, free of moral and political restraints.

References

- Ashworth, Tony. 1980. Trench Warfare, 1914-1918: The Live and Let Live system. London: Macmillan.

- Bairnsfather, Bruce. 1917. Fragments from France. New York and London: The Knickerbocker Press.

- Pinker, Steven. 2011. The Better Angels of our Nature: The Decline of Violence in History and its Causes. London: Allen Lane.

Back to the USSR: National Security in the Soviet Economy

Writing about web page http://postnauka.ru/video/30259

In Moscow 18 months ago, I made some short videos for Postnauka, a Russian science and social-science video magazine. One of the videos I made was about the security dimension of the Soviet economy. Under the heading of "security" I had in mind both external (mainly military) security and internal political security. The Postnauka people published it on line in August this summer and I think they forgot to tell me so I noticed it only recently. Anyway here is the interview(in English, just over 16 minutes).

Here's a translation of the Russian-language introduction on the Postnauka web page:

What approaches have been used to study the history of the Soviet economy? Why is it difficult to investigate the various influences on the Soviet economy? University of Warwick Professor Mark Harrison explains how to uncover the hidden connections between the agencies of government in the "Serious Science" project established by the Postnauka team.

At first [after the opening of the archives] researchers looked into just two aspects. One was the actual scale of the Soviet military-industrial complex, which was not the whole economy but still a very important part of it and it affected the whole economy, for example, through mobilization planning. So understanding the scale of Soviet rearmament and the military-industrial complex was one aspect, and the other was the effort to better understand the general context of the "great breakthrough" of the first five year plan of the 1920s and the transformation of the Bolshevik party into Stalin's personal power.

I want to mention here another researcher, Vladimir Kontorovich. He drew attention to the need to listen to what the Bolsheviks actually said. In Western economics there is often neglect of what politicians say because we think of our own politicians and their broken promises; we know that politicians lie, so why read what they write as opposed to looking at the outcomes? Kontorovichhas argued that we ought to take seriously what Lenin and Stalin said about their economic goals. In my view if you consider carefully what they wrote about economics you can see some things that emerged from the Bolshevik strategy and the Soviet system of power.

It's difficult for historians to evaluate the role of the security services in economic policy and decision making partly because we have access to the security archives only for the 1930s. Now this situation is changing because a group of independent states that were Soviet republics have chosen a different political path and some of them have opened thei security archives. These are primarily the Baltic countries — Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia; Ukraine (to some extent) and Georgia have also opened their archives, so now we can find out how the Soviet security service operated in the [Soviet] borderlands. Based on this, we can try to infer how they worked in the Soviet Union as a whole.

To give an example of the kind of research that is now possible, over the last couple of years Inga Zaksauskiene of the History Faculty of Vilnius University and I have been writing a paper entitled "Counter-Intelligence in a Command Economy." Our paper, bassed on research in the documents of the Lithuania KGB held on microfilm at the Hoover Archive, has just been acceped for publication by the Economic History Review. Here's the abstract:

We provide the first thick description of the counter-intelligence function in a command economy of the Soviet type. Based on documentation from Soviet Lithuania, the paper considers the KGB (secret police) as a market regulator, commissioned to prevent the disclosure of secret government business and forestall the disruption of government plans. Where market regulation in open societies is commonly intended to improve market transparency, competition, and fair treatment of consumers and employees, KGB regulation was designed to enforce secrecy, monopoly, and discrimination. One consequence of KGB regulation of the labour market may have been adverse selection for talent. We argue that the Soviet economy was designed to minimize the costs.

And here is a preprint.

December 13, 2014

Was the Soviet 1923 Male Birth Cohort Doomed by World War II?

Writing about web page http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/podcasts/radio4/moreorless/moreorless_20141213-0600d.mp3

Tim Harford's BBC Radio programme "More or Less" asked me to comment on a claim that is widely repeated on the internet, for example on Buzzfeed:

Almost 80% of the males born in the Soviet Union in 1923 did not survive World War II.

My answer

Here's the numbers I worked from on the programme(in thousands, rounded to the nearest hundred thousand). Each of the lines is sourced below.

- Males born in the Soviet Union in 1923: 3,400

- Infant (0-1) mortality: 800

- Childhood (1-18) mortality, famine, and terror: 800

- Surviving to 1941: 1,800

- Wartime mortality: 700

- Surviving to 1946: 1,100

My comment

The Buzzfeed claim is overstated, although not by a wide margin. Around two thirds (more exactly, 68%) of the original 1923 male birth cohort did not survive World War II. But the war is not the most important reason for the poor survival rate; almost half of them died before the war broke out.

The babies of 1923 were born at an awful time and faced a dismal future. The country they were born in was poor and violent. Between 1914 and 1921 their families had endured seven years of war and civil war, immediately followed by a major famine. Their society lacked modern sanitation, immunization programmes, and antibiotics. Rates of infant mortality and childhood mortality were shockingly high. Moreover, violence and famine were not a thing of the past. The 1923 cohort would be aged nine in the first year of the next major famine (1932) and fourteen in the year of Stalin's Great Terror (1937). They turned eighteen just as Germany attacked their country (1941).

The German invasion of 1941 was a deep national trauma. The young men born in 1923 were inexperienced conscripts for an army that was repeatedly shocked, taken by surprise, encircled, and pulverized. It suffered terrible losses. In the first six months, three million troops were killed or taken prisoner, and most of those taken prisoner did not survive. If they survived that, they faced more years of battlefield attrition or else and exhaustion on the home front. In all the Soviet Union suffered around 25 million war deaths, plus or minus a million (Harrison 2003). Red Army deaths alone were 8.7 million.

The overall mortality of the Soviet 1923 male birth cohort can be distributed over four stages of life. Around 800 thousand died in their first year. These died of birth defects, disease, accidents, abuse, and neglect. Another 800 thousand died between the ages of 1 and 18 from a range of causes that included those just mentioned and extended beyond them to famine and political violence. Then, from age 18 to 22, another 700 thousand were carried off in the war. That left just over a million to live on into middle and old age.

It may be surprising that war was not the major cause of premature death up to 1946 for the young men born in 1923. But in this there should be two harsh reminders. The first reminder is that nature is wasteful: everywhere until very recently only a minority of babies survived to adulthood, even in peacetime. This was still the situation for the Soviet Union in 1923. The second reminder is that 700,000 wartime deaths from a single birth cohort of young men is still a shocking figure. It is, for example, more than twice the total number of British military and civilian casualties in World War II.

My working

I took the data from Andreev, Darskii, and Khar'kova (1993). These three Russian demographers reworked the Soviet census and registration records immediately after the collapse of the Soviet Union opened up the archives for independent research. Everyone abbreviates the reference to ADK so I will too. ADK (p. 118) give the total of births in the Soviet Union in 1923 as 6,523 thousand. Assuming a normal male/female split of 107/100, male births were 3,372 thousand. This is the size of the 1923 male cohort that we have to reckon with.

ADK do not give exact figures for the numbers of the 1923 male cohort surviving to 1941 and 1946, but you can read them off a chart (p. 79) as approximately 2 million and 1.2 million, implying 800 thousand wartime deaths. For our purpose, however, these figures require adjustment for border changes. In 1946 Soviet borders were wider than in 1923. In 1939/40 the Soviet Union expanded to absorb the Baltics, eastern Poland, and some other territories. Because of this the population was boosted (p. 118 again) from 168.5 to 188.8 million, or about 12 percent). So we need to multiply by 168.5/188.8 to take the 1923 male birth cohort as reported in 1946 back to the original borders of 1923. This gives survivors to 1941 as 1,785 thousand, wartime deaths as 714 thousand, and 1,071 thousand survivors to 1946.

A cross-check

If these figures are right, two thirds (rather than 80 per cent) of the original 1923 male birth cohort were dead by the end of World War II. But the war was not the largest cause of death, for nearly half of them were dead by 1941, before the war broke out. How reasonable is that?

There are two factors that explain heavy peacetime mortality. First, infant mortality: ADK give infant mortality in 1923 (p. 135) as 229 per thousand (with 220 as a lower bound and 238 as an upper bound). Applying their central estimate gives 770 thousand deaths in the first year of life, leaving 2,600 thousand survivors to 1924.

Second, childhood mortality, famine, and violence. For consistency with 1,785 survivors in 1941, we obtain deaths over the period from 1924 to 1941 as a residual, and the number of these is found to be 814 thousand, which is a larger number than the number of deaths in the first year of life. Is that reasonable? Elsewhere (pp. 19, 20. 35), ADK give survival tables for male newborns based on the three interwar censuses, from which it is clear that male child mortality over 1 to 3 years was never much less than over 0 to 1. Taking into account famine, terror, etc., a figure for 1-18 mortality that slightly exceeds 0-1 mortality is plausible.

Soviet demography is not an exact science. All these figures are more fuzzy than might appear at first sight -- one reason my opening summary rounds everything to the nearest hundred thousand. On the same programme you can hear Mike Haynes (he and I reach similar conclusions) reminding listeners that the error margin on Soviet war deaths, plus or minus one million, is another number that is greater than the number of British war deaths. The one thing that saves us from complete confusion is that demographic accounts have to be consistent, both internally and externally. The requirement of consistency helps us to judge that some claims are reasonable and others are ruled out.

References

- Andreev, E. M., L. E. Darskii, and T. L. Kharkova. 1993. Naselenie Sovetskogo Soiuza, 1922-1991. Moscow: Nauka.

- Harrison, Mark. 2003. Counting Soviet Deaths in the Great Patriotic War: Comment. Europe-Asia Studies 55:6, pp. 939-44.

Mark Harrison

Mark Harrison

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…