All 16 entries tagged History

View all 182 entries tagged History on Warwick Blogs | View entries tagged History at Technorati | There are no images tagged History on this blog

July 29, 2012

The China Deal: Why China's economic success is fragile

Writing about web page http://ideas.repec.org/p/cge/warwcg/91.html

Why has China succeeded where Russia failed?

The explanation that is most widely shared is that the Chinese rulers kept political control and used it to reform the economy gradually. They pursued Deng Xiaoping's "four modernizations" (of agriculture, industry, defence, and science and technology) but rejected calls for the so-called "fifth modernization" (democracy). In the Soviet Union at the same time, in contrast, Mikhail Gorbachev abandoned the levers of totalitarian control. He allowed the Berlin Wall to be pushed over. The Soviet communist party imploded; insiders "stole the state." The Soviet Union collapsed and Russia entered a decade of near anarchy.

This explanation has obvious appeal but is incomplete on closer inspection. It is widely believed that the Soviet leaders did not try the China solution of gradual economic reform without political reform. The historical record shows, however, that this is untrue. Over a period of many years, while their system of one-party rule was completely intact, the Soviet leaders tried all the reforms that the Chinese communists followed to revitalize their economy. This included several experiments with a household responsibility system, the so-called zveno, in agriculture (1933, 1947, and 1966); a regional decentralization (from 1957 to 1965); and several rounds of public sector reform (beginning in 1965), culminating in new laws to reduce the compulsory obligations on state-owned enterprises, allowing them to supply the market directly at higher prices (1987), and to permit private enterprise (1988).

In other words, rash political reforms are not the factor that decided why communism failed in Russia. The collapse of Soviet rule came only after the gradual economic reform initiatives that worked in China failed in Russia.

We must look somewhere else, therefore, to explain China's success. In a survey of Communism and Modernization, I suggest that the answer must begin with China's capacity for continuous policy reform. To break out of relative poverty and catch up with the world technological leader, an economy must undergo continuous reform of its policies and instutions. Continuous policy reform is fragile. The reason for its fragility is that, as the economy undergoes successive stages of modernization, policy reform at each stage must infringe upon the vested interests formed in the previous stage. Where continuous reform becomes blocked (as in Italy, for example), the economy will lag and fall behind. From the 1970s, the Chinese economy institutionalized a capacity for continuous policy reform. This is what has enabled China's spectacular rise.

Continuous policy reform was a by-product of China's system of "regionally decentralized authoritarianism" (described by Xu 2011). This system set China's 31 provincial leaders to compete with each other economically and also gave them considerable freedom to choose how to do so. Those leaders who could make their provincial economy grow faster, if necessary by attracting labour from neighbouring provinces, would rise politically; the laggards would fall. Such incentives were very strong.

Deng Xiaoping allowed the provincial bosses to strike a "China deal" that created new space for private business to come out of the cold and thrive within market socialism. This opening of markets to private entrepreneurs, modest at first, became much more radical than the limited "deals" struck in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. Economic reforms under European communism gave legitimacy, at most, to low-powered, short-term profit-based incentives, insider lobbies, and shady sideline trading networks.

In China the main limit that was placed on market access was political: China's new business class must continuously demonstrate its loyalty to the one-party state. The best way to prove loyalty was through political and family connections to the regime. This raised the danger of the new business class exploiting their personal links to power to grow rich without economic effort. One answer, but an imperfect one as we see today, was to expose them to foreign competition. In fact, there was more product market competition in export markets than across China's internal provincial borders.

A crucial and completely accidental advantage on China's side was its size. The Chinese population was so large that its 31 provinces each formed an economic region with tens of millions of people -- the size of a large Western European country. In contrast, the Soviet Union decentralized economic management across a much larger number of much smaller provinces, averaging little more than a million people each. Unlike a Chinese province, the typical Soviet province was highly dependent on its neighbours. The danger was that a Soviet provincial boss could gain more by sabotaging his neighbours than by honest effort within his own limited sphere. In the Soviet Union regional rivalry turned out to carry high costs and few if any benefits.

If regional rivalry was not productive within the Soviet Union, why did it not work across Eastern Europe as a whole? After all, each East European country had considerable freedom to experiment with national economic models, and was more like a Chinese province in size and diversity than a Soviet province. Nonetheless, international competition did not work any better than interprovincial rivalry. Most likely, East European communist leaders had too much job security and tenure, did not depend on doing better than their neighbours to keep their jobs, could not be promoted to Moscow, and, even if they succeeded economically, could not build on success to attract labour from their neighbours because international borders, even within the communist brotherhood of nations, were rigidly sealed.

It may also have been a factor that East European and Soviet leaders just did not "get" continuous policy reform. They thought catching-up growth could be achieved by one-off reforms or interventions. It is also a good question whether Chinese leaders "got" continuous policy reform, or whether they stumbled across a design for it by accident.

Either way, the result was this: The recipe that happened to make communism work in China was tried and did not work in Europe. That raises a question of vast proportions: Will the same recipe continue to work in China's future?

Here we come back to the fragility of continuous policy reform. China's level of output per head has multiplied several times over the level of the 1970s. It must multiply several more times before China can approach the level of the world's richest countries. This is a very long haul. For China to maintain the continuity of policy reform over the distance is beyond unlikely. At some point, some coalition of interests is bound to form that will be strong enough to block it, at least for a time. At that time China's oligarchy must be willing to intervene on the side of movement, not stability. If not, the China deal will come unstuck.

References:

Harrison, Mark. 2012. Communism and Economic Modernization. CAGE Working Papers no. 92. University of Warwick. Repec handle http://ideas.repec.org/p/cge/warwcg/91.html.

Xu, Chenggang. 2011. The Fundamental Institutions of China's Reforms and Development. Journal of Economic Literature 49:4, pp. 1076-1151. Repec handle http://ideas.repec.org/a/aea/jeclit/v49y2011i4p1076-1151.html.

May 28, 2012

Seventy Years Ago: The Week the Tide Began to Turn

Writing about web page http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/events/wwii-pac/midway/midway.htm

Seventy years ago this week, the world looked unspeakably grim.

By the end of May 1942, Germany had occupied France, Belgium, Netherlands, and Luxemburg; all of Eastern Europe not already under control of its allies Bulgaria, Hungary, and Romania, including the Baltic, the Ukraine, and a large chunk of Russia; Greece and Yugoslavia; and the former Italian colonies of North Africa. Italy wasn't helping much, but in the Far East Japan had occupied much of China, all of Indochina, Indonesia, Malaya (including Singapore), the Philippines, and part of Burma. German bombers were battering Britain's cities; German submarines were sinking Allied shipping at half a million tons a month. In Russia and Ukraine the German Army was launchng new offensives; at Khar'kov, in a battle that ended seventy years ago today, the Red Army lost a quarter of a million men. Across Europe and East Asia, millions of non-combatants were being machine-gunned, gassed, starved, and worked to death.

At this very moment, beneath the surface of these terrible events, the tide of the war was beginning to turn. Up to that time, Axis forces were advancing on all fronts. Within a few months they were in retreat everywhere.

In 1942 the war was fought in three main theatres: the Pacific, the Mediterrean, and the Eastern front. In each theatre the turning point of the war was marked by a decisive battle. These were the Battles of Midway (June 4 to 7), the seventieth anniversary of which we are about to mark; El Alamein (July 1 to 30 and October 23 to November 4); and Stalingrad (September 13 to February 2, 1943).

In obvious ways these battles could not have been more different: Midway in the remote northern Pacific, Alamein in the desert sands of Egypt, and Stalingrad in the smoking ruins of a great city on the Volga river. These battles differed also in the orders of magnitude of the forces involved. Japanese losses in four days at Midway were five ships, 250 aircraft, and 3,000 men. German losses in two weeks at the second battle of Alamein were 800 tanks and guns and 30,000 men, and in five months at Stalingrad 7,500 tanks and guns and three quarters of a million men killed or missing. Red Army losses at Stalingrad alone were half a million; do not forget these figures if you want to understand how powerfully the war continues to stir national feeling in Russia.

In other respects, these battles had important common features. Each began with an enemy offensive. The Japanese planned to use Midway Island as a launching pad from which to invade Hawaii. The Germans planned to drive the British out of North Africa; if the Mediterranean could not be an Italian lake, then let it be a German one. From Stalingrad the Germans planned to seal off the Caucasian oilfields and turn north to take Moscow from the rear.

After the offensive came the counter-offensive, which in each case took the enemy by surprise. After the successful surprise attack on the U.S. Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the Japanese believed they had finished American naval power. Just six months later, in the summer of 1942, the U.S. Navy was already three times the size of the previous year. Such was the speed of mobilization of America's industrial power, and the resilience of American national feeling, both of which had been entirely discounted in Tokyo and Berlin. The same underestimation of Allied reserves was present in the calculations of the Axis commanders at Alamein and Stalingrad.

The Allied victories of 1942/43 were no accident. Underlying them was the translation of Allied economic power into fighting power. In 1941 the Axis Powers were poised for victory. But victory would be theirs only if they exploited the advantage of the aggressor to the full. With a potential coalition of economically more powerful enemies ranged against them, they had to win every campaign quickly and avoid a stalemate at all costs. Had they done so, the war would have been over and they would have won.

Economic mobilization, the translation of economic power into fighting power, takes time. The Allies bought this time with "blood and treasure." First came the British refusal to surrender in the summer of 1940, followed by the Battle of Britain. Next came the U.S. Lend Lease Act of March 1941 which offered American aid to the British (and a few months later to the Soviet Union). The third thing was the unexpected -- in German eyes, often senseless -- resistance of the Red Army in the summer and autumn 1941, which led through appalling losses to the failure of the German invaders to take Leningrad and Moscow before the end of the year.

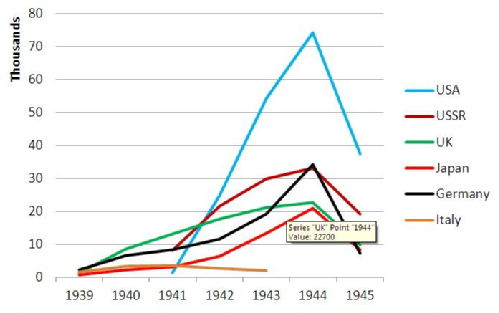

Source: Harrison (1998, pp. 15-16).

Having bought time, the Allies used it to mobilize their economies. The chart shows the production of combat aircraft by the main powers year by year through the war. It illustrates how, during 1942, Allied -- and especially American -- mobilization rapidly tilted the military-economic balance against the Axis. The Allies began to outproduce Germany and Japan in aircraft, and also in munitions generally, by a substantial multiple. This advantage persisted through the end of the war, despite belated mobilization of the German and Japanese war economies. In 1942, however, the grit and bloody determination of Allied soldiers, sailors, and airmen was still required to turn material predominance into victory on the battlefield. Midway, Alamein, and Stalingrad were the signals that this had been achieved.

Why was the struggle so much, much more intense on the Eastern front? From mid-1941 through mid-1944 this was where 90 percent of German fighting power was focused. To occupy the territory of Ukraine and European Russia, kill the Jews, decimate the Slavic population, and resettle this vast landmass as a German colony, was Hitler's prime objective. The Soviet economy, although large, remained poor and industrially less developed, so that it was on the Eastern front that German resources were most evenly matched. The Allies' material advantages were much greater elsewhere. If the Axis could not win in Russia, it would not win anywhere else. On the Eastern front a war of mutual annihilation developed, in which both sides threw everything they had and more into the scales. As I discussed in a paper entitled "Why Didn't the Soviet Economy Collapse in 1942?" (Harrison 2005), Hitler had every right to expect final victory. The Soviet Union only just managed to retain a critical advantage over Germany, based on mass production, colossal sacrifice, and utter ruthlessness.

Up to the summer of 1942, the forces of the Axis were advancing everywhere; from the beginning of 1943 they retreated on all fronts. After this it was no longer possible for the Axis powers to win the war against the economically more developed, more mobilized, and more powerful Allies. One of the most horrifying faces of the war is seen in the fact that, despite this, years of intense fighting still lay ahead. Through 1943, 1944, and into 1945 the German and Japanese Armies and Navies retreated continuously, killing and being killed every day and every inch of the way, maintaining discipline and cohesion, not giving up until the last possible moment. Every day of those years their governments persisted in genocidal policies that destroyed millions of lives through famine, overwork, and systematic mass killing.

Without Midway, Alamein, and Stalingrad our world today would be far different from the one we know. The Axis powers might have ended the war victoriously, with consequences that we can only guess at. Alternatively, the war would have been dragged out in some other way, but there would have been no Allied victory in 1945. Or perhaps there could still have been victory in 1945, but the evolution of events would have been entirely different. Regardless of events on the battlefield, by the summer of 1945 the Americans would have had the atomic bomb. If the war still raged in Europe, the first victims of atomic warfare would more likely have been German than Japanese.

References

- Harrison, Mark. 1998. Economic Mobilization for World War II: an Overview. In The Economics of World War II: Six Great Powers in International Comparison, pp. 1-42. Edited by Mark Harrison. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Harrison, Mark. 2005. Why Didn't the Soviet Economy Collapse in 1942? In A World at Total War: Global Conflict and the Politics of Destruction, 1939-1945, pp. 137-156. Edited by Roger Chickering, Stig Förster, and Bernd Greiner. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. RePEc handle: http://ideas.repec.org/p/wrk/warwec/603.html

May 14, 2012

The Dam Busters: Their Place in (Economic) History

Writing about web page http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/knowledge/culture/dambusters

Written for Warwick's Knowledge Centre in preparation for Wednesday night's sixty ninth anniversary of the dam raids.

The dams of Germany’s industrialized Ruhr valley were an obvious target for the Royal Air Force Bomber Command in World War II. The dams supplied hydroelectric power and water for cities, steel making, and canal transport. In turn, these provided the means to supply Germany with the tanks, aircraft, guns, shells, and ships required for Hitler’s war.

Operation Chastise, the Dam Busters’ raid, took place on the night of May 16/17, 1943. Tactically, it was a partial success. The Möhne and Eder dams collapsed, but the Eder reservoir was of secondary importance and the dam on the Sorpe was not seriously damaged. Some small towns and industrial facilities were flooded, and some roads were washed away. There was a temporary loss of water production and electric power. At least 1,300 civilians died; more than half were Ukrainian forced labourers. Eight of the 19 aircraft were lost and 53 of the 133 aircrew killed.

What were the effects of the dam raids on Germany’s war economy? From the beginning of 1942 through May 1943, German war production expanded at about 5 per cent a month. At the time of the dam raids it was already more than twice the level of two years previously when Germany had been about to launch the greatest land invasion of all time, its attack on the Soviet Union. In the month of the dam raids, however, the increase of German war production was halted and the German economic mobilization marked time for nearly a year.

How much of this was due to the Dam Busters? In 1943 British and American bombers dropped 130,000 tons of bombs on German cities and factories, and ten times that quantity in 1944 (Zilbert 1981). Up to a million German civilians lost their lives (Falk 1995). In this context the dam raids were a pinprick. Thus, while the raid was mounted at an important moment, it would be hard to identify any particular effect of the Dam Busters’ skill and heroism on the German war effort.

The dams were quickly rebuilt and water supplies were restored. Were these indirect costs important? Albert Speer, the minister of armament, had to divert 7,000 forced labourers from building German fortifications in occupied France and Netherlands to rebuild the dams (Speer 1970, p. 281). It has been suggested that this contributed to Allied success in the 1944 D-Day landings (McKinstry 2009), but the claim seems far-fetched. In May 1943 the Germans still had a year to complete their coastal fortifications. Much more important to Allied success on D-Day were numbers, surprise, and the German lack of air cover.

When Operation Chastise was planned, RAF Bomber Command did not take into account either D-Day or the indirect cost to Germany of diverting scarce labour from the fortification of occupied Europe. In fact, the RAF hoped to bomb Germany into defeat before D-Day became necessary. In this way, the operation expressed the persistent belief in a powerful knock-out blow that would somehow disable the German war economy and deprive its armed forces of the means to fight. Somewhere, they thought, if only it could be found and attacked, was a critical weak point of the German war economy that could cause it to collapse. Perhaps the dams were such a weak point.

Speer later suggested that the direct effects of the raid would have been greater if the RAF had organized follow-up raids to disrupt the rebuilding. But the lack of follow-up also expressed the mistaken belief of the time in the efficacy of a single knock-out blow. Two centuries of experience of economic warfare and sanctions (summed up by Olson 1963) have taught us that this belief is generally unfounded.

Bombing Germany did not win the war, but it did bring forward the moment of German defeat. Bombing was highly disruptive and made mobilization ever more costly (see Overy 1994 and Tooze 2006). For a long period the German leaders were able to restrict the consequences to the civilian economy, so that conditions of life, consumption, and work deteriorated but war production could still expand. Civilian life was maintained by the human capacity for adaptation to difficulties and habituation to fear. Disaffection was kept in check by an effective police state, growing hatred of the Allied bombers, increasing awareness of Germany’s own war crimes, and rising fear of the possible consequences of defeat. Requisitioning food and slave labourers from the occupied territories also helped. That was the basis on which Germany was able to fight on against economically more powerful enemies for years.

Only when German territory was directly attacked did the war economy finally unwind. The indirect effects of Allied bombing also helped to bring that moment nearer. Allied bombing weakened the German ground forces because it distracted German air power away from the Eastern Front (against the Red Army) and France (against the 1944 Allied landings). Defending against air attack was very costly for Germany. At the peak of war mobilization, one third of German war production took the form of night fighters, anti-aircraft guns, searchlights, and radar.

Bombing Germany was costly to both sides. On one side the German economy was disrupted and a million civilians died. On the other side 18,000 Allied bombers were lost, along with 100,000 highly trained and educated aircrew.

The Dam Busters were one small element of a total war. They did not provide a breakthrough, but they added to the slowly growing burdens on the German economy, which arose through channels that were largely unintended and unforeseen. The Dam Busters also boosted Allied morale and Churchill’s status with the Americans and the Russians. Without them, the book (Brickhill 1951) and the film of the book could not have been made. These gave a sense of heroism and past glory to many a British schoolboy. I don’t know what the girls thought; we never asked them.

References

- Brickhill, Paul. 1951. The Dam Busters. London: Evans.

- Falk, Stanley L. 1995. Strategic Air Offensives. In The Oxford Companion to the Second World War, pp. 1067-1079. Edited by I. C. B. Dear. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Milward, Alan S. 1965. The German Economy at War. London: Athlone.

- McKinstry, Leo. 2009. “Bomber Harris thought the Dambusters’ attacks on Germany ‘achieved nothing’.” The Telegraph, August 15.

- Overy, Richard J. 1994. War and Economy in the Third Reich. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Speer, Albert. 1970. Inside the Third Reich. London: Macmillan.

- Olson, Mancur. 1963. The Economics of the Wartime Shortage. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Tooze, Adam. 2006. The Wages of Destruction: The Making and the Breaking of the Nazi Economy. London: Allen Lane.

- Zilbert, Edward R. 1981. Albert Speer and the Nazi Ministry of Arms: Economic Institutions and Industrial Production in the German War Economy. London: Associated University Presses.

April 02, 2012

Russia's Great War, Civil War, and Recovery

Writing about web page http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/economics/news/?newsItem=094d43a2365e99f001366436ff461cde

Tomorrow I'm flying to Moscow to collect a prize, which I will share with my coauthor Andrei Markevich. This is the Russian national prize for applied economics, which was announced last week. The prize, sponsored by a consortium of Russian universities, research institutes, and business media, is awarded every second year. The award is for our paper "Great War, Civil War, and Recovery: Russia’s National Income, 1913 to 1928," published in the Journal of Economic History 71:3 (2011), pp. 672-703. A postprint is available here.

The spirit of the paper is as follows. In 1914 Russia joined in World War I. In 1917 there was a revolution, and Russia’s part in that war came to an end. A civil war began, that petered out in 1920. It was followed immediately by a famine in 1921. We calculate that by the end of all this Russia had suffered 13 million premature deaths, nearly one in ten of the population living within future Soviet borders in 1913. After that, the Russian economy recovered, but was soon swept up in Stalin's five-year plans to "catch up and overtake" the West.

We calculate Russia’s real national income year by year from 1913 to 1928; this has never been done before on a consistent GDP basis. National income can be measured three ways, which ought to give the same answer (but rarely do): income (wages, profits, ...), expenditure (consumption, investment, ...), and output (of industry, agriculture, ...). We measure output. Data are plentiful, but of uneven quality and coverage. The whole thing is complicated by boundary changes. Between 1913 and 1922 Russia gave up three per cent of its territory, mainly in the densely settled western borderlands; this meant the departure of one fifth of its prewar population. The demographic accounting is complicated not only by border changes but also by prewar and wartime migrations, war deaths, and statistical double counting.

Our paper looks first at the impact of World War I, in which Russia went to war with Germany and Austria-Hungary. Initially the war went went well for Russia, because Germany found itself unexpectedly tied down on the western front. Even so, Germany quickly turned back the Russian offensive and would have defeated Russia altogether but for its inability to concentrate forces there.

During the war nearly all the major European economies declined (Britain was an exception). The main reason was that the strains of mobilization began to pull them apart, with the industrialized cities going in one direction and the countryside going in another. In that context, we find that Russia’s economic performance up to 1917 was better than has been thought. Our study shows that until the year of the 1917 revolution Russia’s economy was declining, but by no more than any other continental power. While wartime economic trends shed some light on the causes of the Russian revolution, they certainly do not support an economically deterministic story; if anything, our account leaves more room for political agency than previous studies.

In the two years following the Russian revolution, there was an economic catastrophe. By 1919 average incomes in Soviet Russia had fallen to less than half the level of 1913. This level is seen today only in the very poorest countries of the world, and had not been seen in eastern Europe since the seventeenth century. Worse was to come. After a run of disastrous harvests, famine conditions began to appear in the summer of 1920 (in some regions perhaps as early as 1919). In Petrograd in the spring of 1919 an average worker’s daily intake was below 1,600 calories, about half the level before the war. Spreading hunger coincided with a wave of deaths from typhus, typhoid, dysentery and cholera. In 1921 the grain harvest collapsed further, particularly in the southern and eastern grain-farming regions. More than five million people may have died in Russia at this time from the combination of hunger and disease.

Because we have shown that the level of the Russian economy in 1917 was higher than previously thought, we find that the subsequent collapse was correspondingly deeper. What explains this collapse? The obvious cause was the Russian civil war, which is conventionally dated from 1918 to 1920. However, we doubt that this is a sufficient explanation. First, the timing is awkward, because the economic decline was most rapid in 1918 and this was before the most widespread fighting. Second, there are signs that Bolshevik policies of economic mobilization and class warfare were an independent factor spreading chaos and decline. These policies were continued and even intensified for a year after the civil war ended and clearly contributed to the disastrous famine of 1921.

Because of the famine, economic recovery did not begin until 1922. At first recovery was very rapid, promoted by pro-market reforms, but it slowed markedly as the Soviet government began to revert to mobilization policies of the civil-war type. We show that as of 1928 the Russian recovery was delayed by international standards. The result was that, when Stalin launched the first five year plan for rapid forced ndustrialization, the Soviet economy's recovery from the Civil War was not complete. By implication, some of the economic growth achieved under the five-year plans should be attributed to delayed restoration of pre-revolutionary economic capacity.

In concluding the paper, we reflect on the state in the history of modern Russia. It seems important for economic development that the state has the right amount of "capacity," not too little and not too much. When the state has the right amount of capacity there is honest administration within the law; the state regulates and also protects private property and the freedom of contract. When the state has too little capacity it cannot prevent outbreaks of deadly violence, and security ends up being privatized by gangs and warlords. When the state has too much capacity it can starve and kill without restraint. In Russian history the state has usually had too little capacity or too much. In World War I the state had too little capacity to regulate the war economy and it was eventually pulled apart by competing factions. Millions died. In the Civil War, the state acquired too much capacity; more millions died.

Andrei Markevich and I have many debts. Our first thanks go, of course, to the sponsors of the prize. After that, we are conscious of owing a huge amount to our predecessors, many of whom should be better known than they are, but I'm going to leave the history of the subject to those interested enough to consult the paper. A number of people helped us generously, especially Paul Gregory, Andrei Poletaev, Stephen Wheatcroft, and the journal editors and referees. Of course, I'm personally grateful to Andrei. It’s hard to say which of us did what (between May 2009 and January 2011 our paper went through exactly 50 revisions), but you’ll see that Andrei is named as first author.

Beyond any personal feelings, I'm thrilled by the recognition of economic history. When he announced the award, the jury chairman Professor Andrei Yakovlev was asked if this wasn't an "unexpected" outcome for an award in applied economics. Yakovlev described it as an "important precedent," recognizing that "explanations of many of the processes that we have seen in Russia in the last twenty years lie in history." He pointed out that most western countries have historical national accounts going back through the nineteenth century (and England's now go back through the thirteenth). Such data help us to understand the here and now, by showing how we got here.

December 19, 2011

Help Me, Daddy

Writing about web page http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-16239693

The death of Kim Jong-il, who ruled North Korea from 1994, reminded me of something a Korean friend told me a few years ago. My friend is an expert on North Korea and told me this "for a fact." Now, I also remember many things I was told "for a fact" in Moscow in Soviet times. This is a fact I've never had the opportunity to verify (and wouldn't know where to look), so I'll put everything in quotes as my friend told it to me.

In order to facilitate his system of personal rule, Comrade Kim Il-sung devised a subcommittee of the party politburo to help him take the most important political and military decisions. The subcommittee had five members, so it became known as the Committee of Five.

Initially, the Committee of Five consisted of Kim Il-sung himself, his son Kim Jong-il, and three other senior party figures.

Note. Kim Il-sung was North Korea's first ruler, and the father of Kim Jong-il. The idea of a Committee of Five is very plausible. A key to the personal power of a totalitarian dictator is "divide and rule." One aspect of divide-and-rule is the compartmentalization of information and responsibilities, so as to minimize the number of people that have an overview of everything. Stalin was a master of this technique, and became notorious after the war for dividing the Politburo members into little subcommittees with limited oversight of particular aspects of policy. These subcommittees became known as the the Quintet, the Septet, and so on. Kim Il-sung's Committee of Five would have excluded other members of the Politburo from general oversight.

Time passed and took its toll. In 1994, Kim Il-sung "went to meet Marx." Following his death, he was promoted to the country's President for Eternity.

Note. This part is certainly true.

Since Kim Il-sung continued to be a state official, although dead, it was clearly out of the question to remove him from the Committee of Five, so he was not replaced. As the three other members of the Committee of Five aged and died, they too were not replaced, probably because there was no one that Kim Jong-il trusted sufficiently. Despite this, the Committee of Five lived on.

Eventually, only Kim Jong-il was left.

My friend concluded (this would be around ten years ago):

At the present time when important political and military decisions must be made, the Committee of Five continues to meet, but when it meets Kim Jong-il is alone in the room. After announcing each item on the agenda, he looks to the ceiling, clasps his hands, and says: "Help me, Daddy!"

This seems like a good precedent for Kim Jong-il's son and successor, Kim Jong-un, to follow. He'd better pray to Daddy; there's no one else he can trust.

October 07, 2011

Afghanistan: Ten Years in a Dead End Street

Writing about web page http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-south-asia-15209793

Marking ten years since the coalition invasion of Afghanistan, former U.S. commander Stanley McChrystal has said that the U.S. and its NATO allies are only a little better than half way towards reaching their war goals. He added:

Most of us -- me included -- had a very superficial understanding of the situation and history [of Afghanistan], and we had a frighteningly simplistic view of recent history, the last 50 years.

Respectfully, I disagree. The problem was not a lack of understanding specifically of Afghanistan's history, or of recent history. The problem was a lack of history in general. They did not understand how our modern world has been created.

The most basic acquaintance with European history since the tenth century would have told them two things.

- Democracy cannot be built overnight. It is a long, long process. A successful democracy depends on the rule of law. The rule of law comes first. Without the rule of law, electoral competition leads swiftly to chaos.

- A society based on patronage and rent sharing -- the kind of state that Afghans had before it was destroyed by a communist coup d'état and Soviet intervention -- can be more stable, more prosperous, and provide more rights than one based on chaos and looting. In fact, the right kind of patronage and rent sharing can foster the rule of law.

Based on ignorance of these two simple things, coalition policies in Afghanistan have been set up to fail from the word Go. We have failed to achieve our goals because the goals were fundamentally misconceived. Tens of thousands of troops and civilians have paid for this with their lives. The immense damage that has been done in Afghanistan and neighbouring countries will persist for decades.

Twenty/twenty hindsight? No. The first time I wrote this was on December 4, 2001. (I updated it on January 9, 2002, and expanded on it in 2009 on July 18 and August 30, and on January 1, 2010.)

I'll be modest about this -- I should be. I have made few predictions that have stood the test of time. Actually I have made few predictions, period. Not having to have a crystal ball is one of the good things about studying history.

I am not saying: Look, I got it right. I'm saying: Look, even I got it right. Why couldn't they?

Maybe because they didn't know the right kind of history.

September 08, 2010

Why Bad Economics is Like Bad Art

Writing about web page http://whatpaulgregoryisthinkingabout.blogspot.com/2010/09/do-we-need-new-economics-101.html

It's economics bashing time again.

The latest to have a go is Gideon Rachman in yesterday's Financial Times. "Sweep economists off their throne!" he demands. He compares economists unfavourably to historians, "archive grubbers" who at least have a sense of modesty about their claims to rigour. He goes on to complain about the "brash certainties, peddled by those pseudo-scientists, otherwise known as economists."

As an economic historian -- and I do grub around in archives -- I suppose I have some sympathy for this view. Only a year ago I was writing about the advantages of history in helping us see what's coming round the next corner.

But as a trained economist I think it misses the point.

Good economics isn't brash and doesn't make unjustified claims of predictive power. Specifically, good economics is not the handmaiden of the journalists and politicians who most want economics to support their nostrums and interventions. My Hoover colleague Paul Gregory makes a powerful case that what our first year students have been learning is still pretty much on the button in today's world. It is, above all, an economics that promotes scepticism, critical thinking, and the avoidance of Type I errors.

My point is that there is not just "economics." There is good economics and bad economics. I don't care if it is radical, liberal, conservative, or what. It's interesting that good economics of every school or tradition has more in common with the good economics of other schools than it has with bad economics of any school.

The problem is that there is always a demand for bad economics and there is also a plentiful supply of it. Why? We won't discuss good and bad physics, because that annoys too many people. Instead, think about bad art. On the supply side, untalented artists exceed the number of talented ones by a large margin. So, bad art is abundant. The same is true of economists; there are many more people like me that are writing about economics, for example, than there are Keyneses, Hayeks, and Friedmans. (I hope there's an even larger number of economists that are worse than me, but that's not for me to say.)

On the demand side, many people (myself included) are not really sure of the difference between good and bad art. Also, there are many reasons why we positively desire bad art: because it is comfortable; because it fits with the decor of the room we live in; because it promotes our fantasies without transcending them; and, particularly, because some critic tells us it is good when it's not. I'm sure I personally subscribe to at least some bad art for each and all those reasons.

The demand for bad economics is similar. In fact, just as critics and reviewers mediate the demand for bad art to the public, bad economics has a bunch of people that do the same job of telling the public to buy it. Who are they? Well, many of them are politicians and, er, journalists.

Since this is about economics, we should also think about price. Good economics is relatively scarce, difficult, and uncomfortable; it's designed for truth, not reassurance. In short, the price is high. Bad economics is abundant, soft, and easily absorbed. For all these reasons, it's cheap.

In fact, I'm fairly sure some of the journalists that are now hopping mad at economists are mad just because they themselves previously invested too much of their beliefs in bad, cheap economics. I once had a rather ill-mannered go at Anatole Kaletsky of The Times on this score. Not all of them are to blame, though, and specifically not Gideon Rachman. (I checked out what Rachman was blogging about before the crisis broke in 2007. At least, he wasn't promoting buy-to-let.)

Anyway, let's get back to sweeping the bad economists off their throne. Get rid of them; then what? Who are we going to ask about the economy? Sociologists? Some guy in the pub? Use common sense?

The trouble is, this is a surefire way of replacing bad economics with ... more bad economics. It was Keynes, himself a great economist, who wrote:

Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.

July 28, 2010

You Have Been Warned

Writing about web page http://www.agentura.ru/timeline/2010/profilactika/

A draft law before the Russian Parliament gives new powers to the FSB (Federal Security Service), the successor to the KGB. It allows the FSB to issue binding warnings to citizens suspected of creating conditions, through negligence, passivity, or incitement, in which crimes might be committed or facilitated. A warning that is ignored can be followed by an unspecified penalty, even though the actions that led to the warning may not be offenses in themselves.

This provision of the draft law restores the legal basis of a function once widely exercised by the KGB. This function was known in Russian as profilaktika, which translates directly as "prophylaxis" or "prevention."

Across the Soviet Union in the late 1960s and early 1970s, for example, the KGB subjected around 15,000 people a year to profilaktika, more than half of them for displaying some sort of overt political unreliability, or having connections with foreigners leading to suspicion of disloyalty (see Rudol'ph Pikhoia, Sovetskii Soiuz: istoriia vlasti, 1945–1991: Moscow 1998, pp. 365-366.) In proportion to the population, this would be about one in 10,000 adult Soviet citizens in each year.

What did profilaktika mean? Evidence of many, many individual cases can be found, for example, in the Lithuania KGB collection of the archive at the Hoover Institution, where I'm working now. How did they work? You could imagine it like this. Out of the blue, you get a call to come into your local KGB office. You really don't know what it's about, but you're on your best behaviour. Sitting behind his desk is a KGB colonel. He asks you what you think of the Soviet Union. Wonderful! You declare. Good, he says.

But in that case, he goes on: How come you told this anti-Soviet joke to your colleagues in the office on Thursday? And on Friday in the bar you repeated the news you heard the day before on Radio Liberty? And on Saturday you were heard cursing your Soviet-made automobile and wishing you had a BMW?

At first you bluster and deny everything. Inside, however, your world is collapsing. You're realizing just how much trouble you're in; your job and your home depend on the state and both are on the line. But that is only the start. Worse, it's dawning on you that your colleagues, your friends, maybe even your family members have been telling tales about you to the KGB. You're on your own.

You crumble. You start to make excuses: You were tired and under stress, you've always been a bit of an ignorant big mouth, you've been promoted above your competence and this has put you under pressure. You didn't realize how wrong it was. But you do now. Yes, you do, you do.

You promise you will never, ever do such things again. And you really mean it because, short of being physically beaten or locked in a cell, nothing is worse than the state of mind that this profilaktika has put you in. You've been exposed, hurt, humiliated, compromised, and isolated from society: From now on you will trust nobody, not even yourself. In fact, the only honest person in the room is the man in front of you.

The colonel listens as you stammer out your explanations. He is calm and nods a lot. He accepts what you say. When you've done, he closes the file. Go away, he says, and change your ways. We'll keep the information but, as long as you do the right thing from now on, we'll never have to look at it again. As you leave, you thank him for putting you back on the right track.

After you've gone, he makes a note to keep a special watch on you for a few months or a year, just to be sure that you meant it.

Profilaktika was applied to all sorts of cases, from loose morals and rowdy behaviour to indiscreet or unauthorized contacts with foreigners, petty smuggling or currency violations, and to adolescents who, in a place like Lithuania, might get caught up in the romance of anti-Soviet fly-posting or dreams of emigration. In such cases profilaktika was applied to the parents as well as the children.

More than half of all the cases of profilaktika were carried out in the privacy of the KGB offices, but there was also another version of the drama. This was enacted in public meetings. In this case the psychological beating was administered by your own colleagues, your student peers, or the pillars of your neighbourhood community.

For a police state, profilaktika was relatively humane. For hundreds of thousands of people it took the place of arrest and imprisonment, which would have been their fate in Stalin's time. It was also very effective in causing people to change their behaviour. In eight years, according to Pikhoia, out of more than 120,000 people subjected to such treatment, only 150 were subsequently taken to court for an actual offense. That's one eighth of one percent, a recidivism rate that western penal systems can only dream about.

A durable police state cannot be built out of bricks alone. There are building blocks like the security police and civilian police, border controls, the control of public assets, the distribution of taxes and resource rents, and media monopolies. In addition, binding agents are needed to assemble the blocks and glue them in place by controlling and coordinating the everyday behaviour of citizens at work, at home, and in the streets. Profilaktika was part of the mortar that held the bricks of the KGB state in position. Looks like it will do so again.

June 03, 2010

Israel and Gaza: When Sanctions Fail

Writing about web page http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/10195838.stm

Israel's deadly assault on the SS Mavi Marmara, the Turkish aid ship bound for Gaza, has evoked worldwide protests and condemnation. Not only that, it promises to undo Israel's three-year blockade of Gaza. Egyptian President Mubarak has ordered the reopening of Egypt's closed border crossing to Gaza. U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has called the situation in Gaza "unsustainable." Israeli relations with Turkey are clearly at risk; responding to popular protests, Turkish Prime Minister Erdogan has called Israel's raid a "bloody massacre."

In many ways Israel's use of sanctions to isolate and weaken the Hamas rulers of Gaza has followed a predictable course, up to and including its calamitous denouement. In the last hundred years trade sanctions and blockades have been employed in many conflicts, from World War I to Iran and North Korea today. It's possible to draw three lessons from this experience:

- Trade sanctions are generally slow to take effect on the country that is sanctioned and have fewer economic effects than expected. This is because, when a country is denied access to commodities that were previously imported, new ways of living without them turn out to be available. Economies are made or substitutes found. There are few limits on the ingenuity that can be brought to bear, provided the will is there. Even poor communities find workarounds. Of course, trade sanctions do make everyday life more difficult and raise the costs of resistance.

- Trade sanctions are usually very costly to impose. The country that imposes them has to meet the economic and political costs of enforcement. The economic costs alone can be large or small depending on the particular situation, but these are at least fairly predictable. The political costs are rarely foreseen beforehand, but can turn out to be even more important. For example, trade sanctions generally have strong political effects that are negative from the point of view of the blockading country. Within the blockade, the effect is to stiffen national feeling, which consolidates support around the government. As a result, the will to maintain resistance turns out to be there, whether or not it was there previously.

- Trade sanctions can also have strong political effects on the international community, and these too can be counter-productive. This is because trade sanctions cause collateral damage, some of which hurts the commercial interests and citizens of neutral countries. In turn, this affects neutral opinion. In some circumstances, the result can be to convert neutral countries into allies of the country that is sanctioned. This is not inevitable, however.

Trade sanctions are often imposed in the expectation that they will quickly cause the adversary's economy to break down or, failing that, to cause the adversary government to reach an acceptable compromise. Alternatively, they are advocated by well meaning humanitarians who prefer non-violent ways of changing the adversary's behaviour. But it is hard to think of a case where trade sanctions actually worked in that way.

Historically, trade sanctions generally did worsen the economic conditions of the sanctioned population and signficantly increased the economic costs of maintaining resistance, as intended, although by less than expected. The political effects, in contrast, tended to work in the other direction, making it easier for the sanctioned government to impose the economic costs on its community. Any payoff to the sanctioning power did not materialize in less than several years and often, even then, only when combined with direct military action.

A clear illustration can be found in World War I. From an early stage in the war, Germany imposed a submarine blockade on the British Isles. Since Britain imported more than three quarters of the food calories consumed in peacetime, German naval strategists believed this was a war winning weapon. Eventually, however, the blockade may have done more damage to Germany than to Britain.

How did Britain survive the blockade? Countermeasures included wartime expansion of home agriculture, its restructuring away from meat to cereals, and rigid prioritizing of convoy shipping space. These measures, although costly, were so effective that, despite a large reduction in food imports, there was no deterioration in wartime nutritional standards for the British population. This illustrates well how the principle of substitution can lessen the effectiveness of blockade in comparison to what is expected beforehand.

The blockade was extremely costly for Germany, which had to build and operate hundreds of ocean-going submarines and replace heavy losses at sea in order to sustain a blockade that was only partially effective. The political costs to Germany were even more disastrous. Within Britain, the political effect was to stiffen patriotism and national resistance.

Internationally, Germany's efforts to tighten the blockade led to the sinking of neutral ships, with their cargoes, crews, and passengers, and to the deaths of neutral citizens carried by British ships. As a result, the neutral community became more sympathetic to Britain. In the first years of the war, the most important neutral power was the United States. It was the German policy of unrestricted submarine warfare that progressively antagonized American opinion and brought America into the war in 1917. America's entry into the war ensured Germany's defeat. These effects illustrate how the political costs of trade sanctions can outweigh any benefit to the blockading power.

During World War I, Britain also blockaded German trade. This was achieved bloodlessly, by a combination of the control of surface shipping and diplomatic pressure on Germany's neutral neighbours. Of course this was very costly to Britain but one difference is that Britain did not lose as many friends as Germany. The main reason is that Britain did not need to attack neutral assets or victimize neutral citizens to enforce its blockade of Germany. In contrast, Germany could not attack British trade without sinking neutral ships and shedding neutral blood.

This is now Israel's problem with Gaza. Until recently, both Israel and Egypt had a common policy of opposing the Hamas administration in Gaza by means of trade sanctions. The sanctions have had some positive effects. Syria and Iran have not been able to resupply the Hamas militants with armaments to attack Israel, which no longer faces daily bombardment. But sanctions have not succeeded in bringing Hamas down or changing its goals. They have not freed the Israeli soldier Shalit Gilad. The economy of Gaza has been reduced to a low level but is maintained there by sanction-busting gangs of criminal entrepreneurs whose profits depend on the blockade, on smuggling through it, and on the distribution of smuggled goods.

The aid flotilla, and Israel's heavy handed response, have broken this equilibrium. The siege has been ended, temporarily at least, on the Egyptian border. Having lost the cooperation of Egypt and Turkey, Israel cannot reimpose sanctions without undertaking measures that are likely to further alienate world opinion; possibly, Israel cannot reimpose it at all. In this way the blockade of Gaza has conformed with historical experience.

I say this without considering the morality of the opposing sides and their actions. Israel has the right to defend its citizens against their enemies. But the blockade of Gaza has ceased to be a means to that end.

September 03, 2009

World War II: Hitler and Stalin, Guilt and Responsibility

Writing about web page http://www.reuters.com/article/latestCrisis/idUSL1655337

For Britain, World War II began 70 years ago today. On a personal note, today would also be the 71st wedding anniversary of my mother and father. They married on September 3, 1938; one year later, they heard Neville Chamberlain declare war on Germany. The war didn't stop them from believing in the future; by 1945 they had two baby girls, my older sisters. I'm thinking of them all as I write.

Who was to blame for World War II? This question is not the same as "What was to blame?" World War II had many deep causes. Ultimately, however, the decision for war is a political act, taken by human beings whom we can hold to account for their actions.

So, who was to blame:

- Germany?

In Europe, the guilty men were the leaders of Nazi Germany. Hitler's plan was to build a German Empire in the East, making Germany self-sufficient in food. Hitler intended to conquer, depopulate, and then resettle Russia and Ukraine. This plan, not yet worked in detail, was soon elaborated in parallel with, but somewhat in advance of the much better known plan to exterminate Europe's Jews. Like the "final solution," the Hungerplan was genocidal: it envisaged starving up to 30 million people of the European part of the Soviet Union to death.

Between Germany and the Soviet Union lay Poland and Czechoslovakia; these states had to be destroyed to clear the path into Russia. The attack on Poland on September 1, 1939, in response to which Britain declared war on September 3, was a necessary step towards Hitler's wider goal. Others contributed to the timing of Hitler's decision and played into his hands in various ways. This is the context in which the behaviour of the British, French, Polish, and Soviet governments should be judged.

- Britain and France?

The worst thing for which the British and French were to blame was the Munich agreement of September 1938. By this agreement Chamberlain and Édouard Daladier, the French prime minister, betrayed Czechoslovakia, their ally, by giving part of it away to Germany. They made themselves accessories before the fact of Hitler's crime. Correctly interpreting this as weakness, in March 1939 Hitler broke the agreement and took the rest of Czechoslovakia.

- Poland?

Although not signatories to the Munich agreement, the Poles also played a small role. First, they refused Soviet offers to send troops to defend Czechoslovakia. They suspected Soviet motives; it was less than twenty years since the Red Army's last invasion. (And history after 1945 strongly suggests that their suspicions would have been correct.) Second, when it became clear that Czechoslovakia was up for grabs they grabbed their own slice, a Polish speaking region on their border. In this small way they became accessories after (not before) the fact of the crime. On the scale of guilt, however, it was very minor. Like the British and French, they acted out of weakness. The best way to understand the Polish leaders at this time is that they were both overplaying and trying vainly to improve their hand in a game they hadn't chosen to enter and couldn't win; it is also true that they were willing to do so at the expense of others.

- The Soviet Union?

The responsibility of the Soviet Union is more complex and wide-ranging. The Soviet government -- in other words Stalin who, by this time, was an unquestioned dictator --did several things, the sum of which was far worse than the Anglo-French collusion with Hitler at Munich. It is important that they all came after the Munich agreement. Until Munich, Stalin hoped to deter Hitler through "collective security" -- an agreement with Britain, France, and their allies Poland and Czechoslovakia, to contain Germany. The Munich agreement told Stalin that this was no longer an option. As his least bad remaining option, Stalin decided to collude with Hitler himself.

To the public, the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact (named after the Soviet and German foreign ministers) of August 1939 was simply an agreement between two countries not to attack each other. This in itself was no crime; Moscow had a similar pact with Tokyo that both sides upheld until August 1945. The crime of the pact was its secret clauses. Infamously, it dismembered Poland, which the Soviet Union had previously offered to defend, carving up that country with Germany, and creating the common Soviet-German border across which Hitler would attack less than two years later.

The pact was Hitler's green light to attack Poland, and determined the timing of today's anniversary. By agreeing to it, Stalin became a co-conspirator in Hitler's decision for war. At the same time it is clear that, even without any secret clauses, Hitler was ready to attack Poland anyway. Thus, Stalin made the Soviet Union an accessory to the crime before and after the fact, but he was not the prime mover in the major crime.

Stalin is directly to blame for many other crimes that followed directly from the Soviet occupation of eastern Poland. The very worst of these was his decision to approve the mass shooting of some twenty thousand Polish officers whom the Red Army had taken prisoner. The officers killed in the Katyn woods were not just professional soldiers; they were the elite of Polish society, politics, and business. The only possible reason for the massacre was that Stalin had determined to prevent the reemergence of an independent Poland.

Just as Stalin gave Hitler permission to attack Poland, other clauses, with some later amendment, gave Stalin Hitler's permission to do what he liked around the Baltic. Thus the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact led directly to the destruction of the independent states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, and to the "winter war" in which Stalin tried, at huge cost, to adjust the Soviet border with Finland. Like Poland, the three small Baltic republics suffered political and social decapitation through the imprisonment and deportation of their former elites.

The official Soviet justification of these measures -- at least, of those that were admitted -- was that Stalin was manoeuvring defensively from a position of weakness and was therefore, like the British, French, and Poles, not primarily to blame; through the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, he bought the Soviet Union time to prepare for an eventual war with Germany. On first hearing, this justification sounds a little like what I said about Poland: Stalin was trying to improve his hand in a game he had not chosen to play. I take it half seriously. Stalin feared Hitler, realized that war was almost inevitable, and played for time, although he went on to develop many illusions about the likely timing of war and the margin for avoiding it. The Molotov-Ribbentrop pact did buy time, and he did use the time to prepare.

There are big differences from Poland, however. One is that the Soviet Union was militarily much stronger than Poland and had much more freedom of action. This must undermine Stalin's excuses for behaving badly. Yet Stalin behaved far, far worse than Poland ever did. The annexations, deportations, and mass killings that he authorized did not buy time or friends, and had little or no justification as preparations for war. On the contrary they caused or intensified anti-Russian feeling in the borderlands that persists to this day. The Katyn massacre had nothing to do with defendng against Germany and everything to do with completing the destruction of Polish independence. One thing to remember about Stalin is that it suited him to have tension on his borders, because this played well with the narrative of encirclement that he used to justify his own rule and the repressions that secured it.

Stalin's decisions had profound effects on the timing of World War II and the course that it followed. But they did not cause the war. The war's trajectory was determined first and foremost by the character and aims of the nationalist socialist dictatorship in Berlin. If Germany had been governed by liberals, socialists, or traditional conservatives in the 1930s, there would not have been a war in the heart of Europe. Without Germany at war, there would still have been an Italian war in North Africa and a Japanese war in China, but neither the Japanese nor the Italians would have been brave enough on their own to start wars against Britain or America in the Mediterranean and the Pacific.

It is true that in 1941 Nazi propagandists tried to justify the German attack on the Soviet Union as a defensive reaction to Soviet preparations for an attack on Germany. This explanation. built on speculation at a time when all the Soviet documents were secret, continues to find traction today in some quarters, but the opening of the Soviet archives has found no more hard evidence for it than there was before.

- Italy? Japan?

Italy was also involved, not only as a signatory at Munich but as an empire-builder around the Mediterrranean. And Japan; don't forget that World War II began in Asia in July 1937 when Japan opened full-scale hostilities against China. Mussolini and the Japanese leaders share the guilt for the war.

- Deeper causes?

When we see several countries bent on the same course, we have to suppose that there might be common factors at work, and these factors might go deeper than any one person's calculations. These deeper factors must include the tensions and imbalances left over from World War I, and the devastating impact of the Great Depression. I've written elsewherethat in the long run the main cost of the Great Depresson was not economic but political, in the way it opened up European politics to dictatorships and aggressive warfare.

Does this reduce the guilt of the individual leaders? I don't think so. A criminal gang that exploits the devastation of a natural disaster to loot and kill is still a gang of criminals.

The idea that World War II had underlying causes is sometimes used to shift the focus away from Germany to Russia. Above, I suggested, "No Nazis -- no World War II." A counter-argument is "No Bolsheviks -- no Nazis." The Soviet Union was a frightening neighbour for both Poland and Germany. Before Hitler came to power, the Bolshevik record of government already included class warfare, mass killings, and concentration camps. Between 1918 and 1924 the Bolsheviks had incited several armed insurrections in Germany. The Red Army had invaded Poland as recently as 1920. This record certainly helped Hitler's racial politics and plans for expansion to play well with the German public. It also undermined any Polish inclination to a common front with the Soviet Union against Germany.

At the same time, Germany did not attack the Soviet Union to restore democratic government or property rights to the Russians or anyone else. Hitler did not target only communist countries, nor did he spare Poland and Czechoslovakia on the grounds that they did not have Bolshevik regimes. His war in the East was a grab for land and food, regardless of who would be displaced. Saying that Bolshevism was responsible for this has more than a whiff of blaming the victim for the crime. The Bolsheviks should have been held to account for many crimes of their own, but not this one.

- How does Russia see Stalin today?

The major crime was the world war itself. The primary guilt for it belonged to leaders in Berlin, Tokyo, and Rome. The war unfolded through many stages; at various times Hitler won cooperation from London, Paris, Warsaw, and Moscow. Those who colluded with him did so sometimes under duress, sometimes to play for time. In retrospect this might look weak or foolish, but those who did it did so to avoid war, not to cause it.

Sometimes it was worse than that. On occasion, Hitler's allies of convenience worked with him opportunistically, because it suited their other goals. This applied more than anyone to Stalin, who exploited his temporary truce with Hitler between 1939 and 1941 not only to build up defenses but also to weaken or destroy the previously independent states on his borders. In the course of this the Soviet Union committed crimes on its own account, that did not flow from Germany's crimes.

In spirit, my apportioning of responsibilities for World War II may not be that different from the account offered by Vladimir Putin to the Polesat ceremonies marking the anniversary of the German invasion on September 1. For example, Putin condemned the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact -- although only as a "mistake." He also offered a joint Russian-Polish commission to establish the facts of what happened at Katyn, although the facts are already well documented. Apart from that, what Putin said in Poland is not the problem.

The problem with Russia's present-day administration is not what it says abroad, but what it says at home. To the Russian public President Medevev has declared, in remarks that were notably anti-Polish and anti-European, there can be no debate over

who started the war, which country killed people, and which country saved people, millions of people, and which country, ultimately, saved Europe.

And for professional historians in Russia the message of the Presidential decree of May 15 this year, directed against "attempts to falsify history to the detriment of the interests of Russia," is again that on certain matters debate is to be ruled out -- by law if necessary.

The Soviet Union, led by Stalin, did not cause the war, but everything else in Medvedev's formulation is highly debatable. The Soviet Union certainly killed people in very large numbers for purposes that ought to be condemned. For Poland, Katyn was a national tragedy. It is true that the Soviet Union "saved Europe" from German domination, and "saved people, millions of people" from destruction. But Stalin did this primarily to save himself; it is not clear that he deserves their thanks for that.

As for the people that the Soviet Union saved most directly, its own people and the citizens of the countries that the Red Army "liberated," it saved them in order to subjugate them, and it subsequently killed more than a few of them in repressing their freedom and independence.

Stalin's legacy is complex. It is in Russia itself that well-informed debate, free of government pressure and "patriotic" restraints, is most needed. When polled, for example, most Russians approve of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact but do not know that the Soviet Union invaded eastern Poland under its provisions.

Meanwhile, I'll stop to think for a moment about Roger and Betty Harrison, married under the gathering stormclouds of September 3, 1938, and their war babies.

Mark Harrison

Mark Harrison

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…