All 51 entries tagged Economics

View all 245 entries tagged Economics on Warwick Blogs | View entries tagged Economics at Technorati | There are no images tagged Economics on this blog

April 09, 2013

Margaret Thatcher and Me

Writing about web page http://www.voxeu.org/article/economic-legacy-mrs-thatcher

Like a million other bloggers and tweeters, I woke this morning thinking about Margaret Thatcher, who has just died.

The front page of this morning's Coventry Telegraph calls her "The woman who divided a nation." In the Financial Times, Janan Ganesh notes that those who call her policies "divisive" often wish to avoid a simple fact: "It is almost impossible to do anything significant without enraging some people"; at best, they indulge "the fantasy that her reforms could have been undertaken consensually."

In my heart, at the time, I was enraged by what Margaret Thatcher did. But now she belongs to history. In my head, looking back as an economic historian, I have to acknowledge the necessity of it. When she came to power, our country was a pretty miserable place: stagnant, strife-torn, and full of bullies. Money was more equally distributed than it is now, but money was worth less than power, and power was highly concentrated in the hands of state monopolies, private monopolies, and organized labour. If you are among the many that think heavier taxation and more market restrictions can make a more consensual, peaceful society, you need to take a closer look at this period of our history. In short, Margaret Thatcher did not invent social division and conflict, which were already present, but she redrew the lines in favour of market access and free enterprise.

When the economic historian looks back, what else is there to see? No one has looked back more clearly than my colleague Nick Crafts on yesterday's Voxeu, so I'll leave the last word on that to him.

I'll finish on a personal note. Nothing annoyed me more at the time than what Margaret Thatcher famously had to say about "society," for I am a social scientist and what she appeared to say was that society does not exist:

I think we have gone through a period when too many children and people have been given to understand “I have a problem, it is the Government's job to cope with it!” or “I have a problem, I will go and get a grant to cope with it!” “I am homeless, the Government must house me!” and so they are casting their problems on society and who is society? There is no such thing! There are individual men and women and there are families and no government can do anything except through people.

Yet a close reading shows that Thatcher had in mind something very close to the kind of model that all economists must use to understand the distribution of income in society, based on the idea that income must be produced by some before it can be redistributed to others:

When people come and say: “But what is the point of working? I can get as much on the dole!” You say: “Look” It is not from the dole. It is your neighbour who is supplying it and if you can earn your own living then really you have a duty to do it and you will feel very much better!”

It's a message for today. I didn't want to hear it at the time. Thatcher didn't seem too bothered by that, and that annoyed me even more. It's still hard for me to say it, but it was a good thing she didn't care.

April 03, 2013

North Korea: Dangerous, but Not Crazy

Follow-up to From 1914 to 2014: The Shadow of Rational Pessimism from Mark Harrison's blog

Is the North Korean regime crazy or calculating? Here is a timeline of North Korea's actions since March 10, when I wrote last.

- March 11: North Korea revokes the armistice ending the Korean War in 1953.

- March 12: Kim Jong Un places the North Korean armed forces on maximum alert.

- March 20: Attacks on South Korean news and banking websites, possibly from North Korea.

- March 27: North Korea cuts a military hotline to the Kaesŏng special region (a joint economic project with South Korea).

- March 29: Kim Jong Un places the North Korean armed forces on standby to strike U.S. territories.

- March 30: North Korea warns of a state of war with South Korea.

- April 2: North Korea will restart weapons-related nuclear facilities.

- April 3: North Korea closes entry to the Kaesŏng special region.

In various ways, these are all costly actions. Some are financially costly to Pyongyang, such as restarting nuclear facilities and disrupting Kaesŏng-based production and trade. Other are reputationally costly, because they stake out positions that are hard to retreat from without loss of face. All of them have a common element of danger -- the risk of triggering a ruinous catastrophe.

Why is North Korea doing these things if they are so costly? In a common interpretation, the North Korean regime is crazy. They don't understand the world or know what is good for themselves. I think this is unlikely.

On the basis that the North Korean leaders are not insane, there are several possible ways to think about their actions and understand them, but in the end they all point to the same outcome.

Opportunity cost. While the measures listed above are costly, North Korea believes that it would not find a better alternative use of the resources consumed or put at risk as a result of their actions. There are few profitable opportunities for production in the world's worst economic system. Investing in confrontation may well be, for North Korea, the better alternative.

Diminishing returns.In the past, North Korea has extracted billions of dollars of aid from South Korea and the West by holding its own people hostage and showing a willingness to play with fire. The problem with this strategy is that Western countries and their Asian partners have learned how it works. As a result, the North Korean strategy has run into diminishing returns. Pyongyang can continue to extract an advantage only by going to greater and greater lengths. This means taking greater and greater risks with peace.

Rational pessimism (That's what I wrote about here). North Korea's leaders see two scenarios. In one, there is a peaceful future in which their regime will inevitably disintegrate and howling mobs will drag them into the street and tear them to pieces. In another, there is a high probability of war in which millions might perish but there is some faint chance of regime survival. You wouldn't jump at either, and you might not rush to make a choice. Still, ask yourself: If you were Kim Jong Un, and push came to shove, which would you prefer?

February 04, 2013

Alternatives to Capitalism: When Dream Turned to Nightmare

Writing about web page http://cpasswarwick.wordpress.com/overview-2/peking-conference/proposed-topics/

On Friday evening I found myself debating "Socialism vs Capitalism: The future of economic systems" at the Peking Conference of the Warwick China Public Affairs and Social Service Society. The organizers also invited my colleagues Sayantan Ghosal, Omer Moav, and Michael McMahon, who spoke eloquently. The element of debate was not too prominent because we all said similar things in different ways. I'm an economic historian and the great advantage of history is that it gives you hindsight. Anyway, here is what I said:

Let’s start from some history. There was a time between the two world wars when the capitalist democracies, like America, Britain, France, and Germany, were in a lot of trouble. In 1929 a huge financial crisis began in the United States and went global. There was a Great Depression. Around the world, many tens of millions of farmers were ruined. Tens of millions of workers lost their jobs.

As today, people asked: What was the cause of the problem? One answer they came up with was: Capitalism is the problem. Lots of people decided: the problem is the free market economy! The government should step in to take over resources and direct them! The government should get us all back to work! The government should get us building new cities, power stations, and motorways!

Another answer many of the same people came up with was: Democracy is the problem. Lots of people decided: the problem is too much politics! We need a strong ruler to stop the squabbling! Someone who can make decisions for the nation! Someone who can organize us to build a common future together!

So there was a search for alternatives to capitalism. Different countries tried different alternatives. The alternatives they tried included national socialism (or fascism) and communism under various dictators, like Hitler and Stalin.

What happened next? On average the dictators’ economies did recover from the Depression faster than the capitalist democracies.

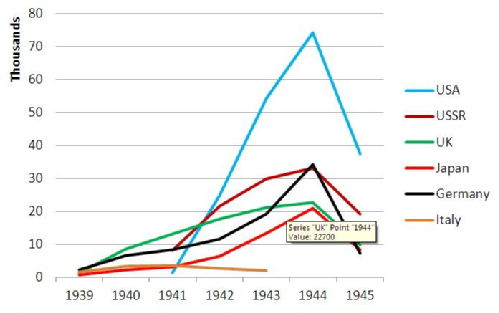

(Here's a chart I made earlier to illustrate the point, but I did not have the opportunity to use it in my talk. Reading from the bottom, the democracies are the USA, France, and the UK; the dictatorships are Italy, Germany, Japan, and the USSR. You can see that Italy does not conform to the rule that the dictators' economies recovered faster. Without Italy, the average economic performance of the dictatorships would have looked even better.)

But solving one problem led to another. Before the 1930s were over the dictators’ policies had already caused millions of deaths. A Japanese invasion killed millions in China (I'm not sure how many). An Italian invasion killed 300,000 in North Africa. Soviet economic policies caused 5 to 6 million hunger deaths in their own country and Stalin had a million more executed.

And another problem: As political scientists have shown, democracies don’t go to war (with each other). Dictators go to war with democracies (and the other way round). And dictators go to war with each other. The result of this was that in the 1940s there was World War II. Hitler, Mussolini, Tojo, and Stalin went to war -- with the democracies and with each other. Sixty million more people died.

After the war, capitalism recovered. In fact, far from being a problem, it became the solution. By the 1960s all the lost growth had been made up. Think of the economic losses from two World Wars and the Great Depression. If all you knew about capitalist growth was 1870 to 1914 and 1960 onwards, you’d never know two World Wars and the Great Depression happened in between.

(To illustrate that point, here's another chart I made earlier, but did not use. It averages the economic performance of Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK, and the USA.)

After World War II fascism and national socialism fell into disrepute, but communism carried on. In China, Mao Zedong’s economic policies caused more deaths. In 1958 to 1962, 15 to 40 million people starved. Communist rule led China into thirty years of stagnation and turmoil. After that Deng Xiaoping made the communist party get its act together. And the communists forgave themselves for their past and agreed to forget about it.

Here's the takeaway.

Liberal capitalism isn’t perfect, but it has done far more for human welfare than communism. It has been the solution more often than the problem. Last time capitalism experienced some difficulties, many countries went off on a search for alternatives. That search for alternatives led nowhere. It wasn’t just unproductive. It was a terrible mistake that cost many tens of millions of lives. Lots of people have forgotten this history. Now is a good time to remember it.

Postscript. At one point I thought of calling this blog "Alternatives to capitalism: the search for a red herring" (a "red herring" is something that doesn't exist but people look for it anyway.) But I realized that would have been wrong, because alternatives to capitalism have actually existed. The problem with the alternatives is not that we cannot find them. It is that the people who went searching for them fell into a dream and woke up to a nightmare.

October 15, 2012

Markets versus Government Regulation: What are the Tail Risks?

Writing about web page http://ideas.repec.org/a/aea/jeclit/v45y2007i1p5-38.html

Tail risks are the risks of worst-case scenarios. The risks at the far left tail of the probability distribution are typically small: they are very unlikely, but not impossible, and once or twice a century they will come about. When they do happen, they are disastrous. They are risks we would very much like to avoid.

How can we compare the tail risks of government intervention with the tail risks of leaving things to the market? Put differently, what is the very worst that can happen in either case? Precisely because these worst cases are very infrequent, you have to look to history to find the evidence that answers the question.

To make the case for government intervention as strong as possible, I will focus on markets for long-term assets. Why? Because these are the markets that are most likely to fail disastrously. In 2005 house prices began to collapse across North America and Western Europe, followed in 2007 by a collapse in equity markets. By implication, these markets had got prices wrong; they had become far too high. The correction of this failure, involving large write-downs of important long term assets, led us into the credit crunch and the global recession.

Because financial markets are most likely to fail disastrously, they are also the markets where many people now think someone else is more likely to do a better job.

What's special about finance? Finance looks into the future, and the future is unexplored territory. Only when that future comes about will we know the true value of the long-term investments we are making today in housing, infrastructure, education, and human and social capital. But we actually have no knowledge what the world will be like in forty or even twenty years' time. Instead, we guess. What happens in financial markets is that everyone makes their guess and the market equilibrium comes out of these guesses. But these guesses have the potential to be wildly wrong. So, it is long-term assets that markets are most likely to misprice: houses and equities. When houses and equities are priced very wrongly, chaos results. (And in the chaos, there is much scope for legal and illegal wrongdoing.)

When housing is overvalued, too many houses are built and bought at the high price and households assume too much mortgage debt. When equities are overvalued, companies build too much capacity and borrow too much from lenders. To make things worse, when the correction comes it comes suddenly; markets in long term assets don't do gradual adjustment but go to extremes. In the correction, nearly everyone suffers; the only ones that benefit are the smart lenders that pull out their own money in time and the dishonest borrowers that pull out with other people’s money. It's hard to tell which we resent more.

If markets find it hard to price long term assets correctly, and tend to flip from one extreme to another, a most important question then arises: Who is there that will do a better job?

It's implicit in current criticisms of free-market economics that many people think like this. Financial markets did not do a very good job. It follows, they believe, that someone else could have done better. That being the case, some tend to favour more government regulation to steer investment into favoured sectors. Others prefer more bank regulation to prick asset price bubbles in a boom and underpin prices in a slump. The latter is exactly what the Fed and the Bank of England are doing currently through quantitative easing.

Does this evaluation stand up to an historical perspective?

We’re coming through the worst global financial crisis since 1929. Twice in a century we've seen the worst mess that long-term asset markets can make -- and it's pretty bad. A recent estimate of the cumulative past and future output lost to the U.S. economy from the current recession, by David H. Papell and Ruxandra Prodan of the Boston Fed, is nearly $6 trillion dollars, or two fifths of U.S. output for a year. A global total in dollars would be greater by an order of magnitude. What could be worse?

For the answer, we should ask a parallel question about governments: What is the worst that government regulation of long term investment can do? We'll start with the second worst case in history, which coincided with the last Great Depression.

Beginning in the late 1920s, the Soviet dictator Stalin increasingly overdid long term investment in the industrialization and rearmament of the Soviet Union. Things got so far out of hand that, in Russia, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan in 1932/33, as a direct consequence, 5 to 6 million people lost their lives.

How did Stalin's miscalculation kill people? Stalin began with a model that placed a high value (or “priority”) on building new industrial capacity. Prices are relative, so this implied a low valuation of consumer goods. The market told him he was wrong, but he knew better. He substituted one person’s judgement (his own) for the judgement of the market, where millions of judgements interact. He based his policies on that judgement.

Stalin’s policies poured resources into industrial investment and infrastructure. Stalin intended those resources to come from consumption, which he did not value highly. His agents stripped the countryside of food to feed the growing towns and the new workforce in industry and construction. When the farmers told him they did not have enough to eat, he ridiculed this as disloyal complaining. By the time he understood they were telling the truth, it was too late to prevent millions of people from starving to death.

This case was only the second worst in the last century. The worst episode came about in China in 1958, when Mao Zedong launched the Great Leap Forward. A famine resulted. The causal chain was pretty much the same as in the Soviet Union a quarter century before. Between 1958 and 1962, at least 15 and up to 40 million Chinese people lost their lives. (We don’t know exactly because the underlying data are not that good, and scholars have made varying assumptions about underlying trends; the most difficult thing is always to work out the balance between babies not born and babies that were born and starved.)

This was the worst communist famine but it was not the last. In Ethiopia, a much smaller country, up to a million people died for similar reasons between 1982 and 1985. If you want to read more, the place to start is “Making Famine History” by Cormac Ó Gráda in the Journal of Economic Literature 45/1 (2007), pp. 5-38. The RePEc handle of this paper is http://ideas.repec.org/a/aea/jeclit/v45y2007i1p5-38.html.

Note that I do not claim these deaths were intentional. They were a by-product of government regulation; no one planned them (although some people do argue this). At best, however, those in charge at the time were guilty of manslaughter on a vast scale. In fact, I sometimes wonder why Chinese people still get so mad at Japan. Japanese policies in China between 1931 and 1945 were certainly atrocious and many of the deaths that resulted were intended. Still, if you were minded to ask who killed more Chinese people in the twentieth century, the Japanese imperialists might well have to cede first place to China's communists. However, I guess there is less national humiliation in it when the killers are your fellow countrymen than when they are foreigners.

To conclude, no one has the secret of correctly valuing long term assets like housing and equities. Markets are not very good at it. Governments are not very good at it either.

But the tail risks of government miscalculation are far worse than those of market errors. In historical worst-case scenarios, market errors have lost us trillions of dollars. Government errors have cost us tens of millions of lives.

The reason for this disparity is very simple. Markets are eventually self-correcting. "Eventually" is a slippery word here. Nonetheless, five years after the credit crunch, worldwide stock prices have fallen, house prices have fallen, hundreds of thousands of bankers have lost their jobs, and democratic governments have changed hands. That's correction.

Governments, in contrast, hate to admit mistakes and will do all in their power to persist in them and then cover up the consequences. The truth about the Soviet and Chinese famines was suppressed for decades. The party responsible for the Soviet famine remained in power for 60 more years. In China the party responsible for the worst famine in history is still in charge. School textbooks are silent about the facts, which live on only in the memories of old people and the libraries of scholars.

September 19, 2012

A Bad Bargain

Writing about web page http://blogs.spectator.co.uk/coffeehouse/2012/09/a-bad-bargain-we-should-give-up-nationwide-pay-bargaining-for-public-employees/

A thought experiment: Imagine what would happen to the Greek economy if a European trade union managed to secure the same salaries for Greece’s public employees as for their German counterparts. If that sounds like a bad idea to you, then consider the fact that in Britain we already have this arrangement across our country's regions.

Nationwide pay bargaining imposes a limited salary range for all public sector jobs of a given type across our country, so that local pay cannot vary to reflect local conditions. Think about the North East. This is our "Greece," a region where house prices and private-sector wages are lower than elsewhere. The national bargain means that in the North East public employees will be relatively overpaid. In contrast, the South East is our "Germany." There, house prices and private-sector wages are relatively high, so the same job for the same nominal pay will be underpaid. It sounds like the effects should balance out across the country as a whole, but the available research shows that they don’t. On balance, we lose.

In the North East the public sector can easily attract employees. At the same time the private sector is blighted: on the evidence of Giulia Faggio and Henry Overman, firms that could sell to the national or international market and would otherwise have the potential to grow are squeezed because they cannot attract workers away from high-wage public employment. On average, Jack Britton, Carol Propper, and John van Reenan have shown, the residents of the North East get good schools and good health care. But the average does not apply to everyone; as Alison Wolf has argued, the gains go primarily to the pockets of affluence; schools and hospitals in particularly deprived areas within the region still struggle to recruit competent staff.

In the South East, the same research shows, hospitals and schools have struggled to recruit because public employees are relatively underpaid. They rely excessively on agency staff and teaching assistants. The education of children and the health of residents have suffered. Within the South East the losses bear more heavily on more deprived communities, because better-off families can turn to private education and health care.

Do the gains balance the losses? No. Carol Propper and her co-authors have shown that the health and educational losses in regions where public employees are relatively underpaid exceed the gains where the converse applies. It doesn’t all balance out. As a result, our country as a whole is left worse off.

Who gains? Apparently, two minorities. One minority is the public employees in the low house-price, low private-wage regions, who gain real income. Another minority is the national trade union officials who have gained status and power from national bargaining. They achieve this by siphoning influence away from their own grass roots – and money out of the Treasury.

National pay bargaining in the public sector is a mechanism that benefits a few and leaves the community worse off. It demands reform. Individual wage bargaining in the public sector would move the public and private sectors towards a level footing in each region. The overwhelming majority of our citizens would gain. Proposals for individual bargaining are sensible, and this is why I support them.

The Evidence

- Britton, Jack, and Carol Propper. 2012. “Centralized Pay Regulation of Teachers and School Performance.” University of Bristol, Imperial College London, and the Centre for Economic Policy Research. Working Paper. Abstract: “Teacher wages are commonly subject to centralised wage bargaining resulting in flat teacher wages across heterogenous labour markets. Consequently teacher wages will be relatively worse in areas where local labour market wages are high. The implications are that teacher output will be lower in high outside wage areas. This paper investigates whether this relationship between local labour market wages and school performance exists. We exploit the centralised wage regulation of teachers in the England and use data on over 3000 schools containing around 200,000 teachers who educate around half a million children per year. We find that regulation decreases educational output. Schools add less value to their pupils in areas where the outside option for teachers is higher and this is not offset by gains in lower outside wage areas.” Available at: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/cmpo/events/2012/doctoralconference/britton.pdf.

- Faggio, Giulia, and Henry G. Overman. 2012. “The Effect of Public Sector Employment on Local Labour Markets.” London School of Economics, Spatial Economics Research Centre Discussion Paper no. 111. Abstract: “This paper considers the impact of public sector employment on local labour markets. Using English data at the Local Authority level for 2003 to 2007 we find that public sector employment has no identifiable effect on total private sector employment. However, public sector employment does affect the sectoral composition of the private sector. Specifically, each additional public sector job creates 0.5 jobs in the nontradable sector (construction and services) while crowding out 0.4 jobs in the tradable sector (manufacturing). When using data for a longer time period (1999 to 2007) we find no multiplier effect for nontradables, stronger crowding out for tradables and, consistent with this, crowding out for total private sector employment.” Available at http://www.spatialeconomics.ac.uk/textonly/serc/publications/download/sercdp0111.pdf.

- Giordano, Raffaela, Domenico Depalo, Manuel Coutinho Pereira, Bruno Eugène, Evangelia Papapetrou, Javier J. Perez, Lukas Reiss, and Mojca Roter. 2011. The Public Sector Pay Gap in a Selection of Euro Area Countries. European Central bank Working Paper no. 1406. Abstract: Abstract: “We investigate the public/private wage differentials in ten euro area countries (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, Slovenia and Spain). To account for differences in employment characteristics between the two sectors, we focus on micro data taken from EU-SILC. The results point to a conditional pay differential in favour of the public sector that is generally higher for women, at the low tail of the wage distribution, in the Education and the Public administration sectors rather than in the Health sector. Notable differences emerge across countries, with Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain exhibiting higher public sector premia than other countries. Available at http://www.ecb.int/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecbwp1406.pdf.

- Propper, Carol, and John Van Reenan. 2010. “Can Pay Regulation Kill? Panel Data Evidence on the Effect of Labor Markets on Hospital Performance.” Journal of Political Economy 118:2, pp. 222-273. Abstract: “In many sectors, pay is regulated to be equal across heterogeneous geographical labor markets. When the competitive outside wage is higher than the regulated wage, there are likely to be falls in quality. We exploit panel data from the population of English hospitals in which regulated pay for nurses is essentially flat across the country. Higher outside wages significantly worsen hospital quality as measured by hospital deaths for emergency heart attacks. A 10 percent increase in the outside wage is associated with a 7 percent increase in death rates. Furthermore, the regulation increases aggregate death rates in the public health care system.” Repec handle: http://ideas.repec.org/a/ucp/jpolec/v118y2010i2p222-273.html.

- Wolf, Alison. 2010. More than We Bargained For: The Social and Economic Costs of National Wage Bargaining. CentreForum: London. Executive summary: “Britain’s centralised wage bargaining systems are bad for the country and getting more so. They create enormous barriers to the improvement of public services, and to rational decision making at a time of fiscal crisis. They penalise our poorest regions, by distorting their labour markets and standing in the way of economic growth. They do not need to be the way they are; and they do need to be changed. […] Britain needs to rid itself of rigid centralised wage bargaining. These systems are economically harmful, undermine quality in the public services, and perpetuate disadvantage. Swedish experience shows that individual contracts are popular and successful and Britain, too, should make that change.” Available at http://www.centreforum.org/assets/pubs/more-than-we-bargained-for.pdf.

July 29, 2012

The China Deal: Why China's economic success is fragile

Writing about web page http://ideas.repec.org/p/cge/warwcg/91.html

Why has China succeeded where Russia failed?

The explanation that is most widely shared is that the Chinese rulers kept political control and used it to reform the economy gradually. They pursued Deng Xiaoping's "four modernizations" (of agriculture, industry, defence, and science and technology) but rejected calls for the so-called "fifth modernization" (democracy). In the Soviet Union at the same time, in contrast, Mikhail Gorbachev abandoned the levers of totalitarian control. He allowed the Berlin Wall to be pushed over. The Soviet communist party imploded; insiders "stole the state." The Soviet Union collapsed and Russia entered a decade of near anarchy.

This explanation has obvious appeal but is incomplete on closer inspection. It is widely believed that the Soviet leaders did not try the China solution of gradual economic reform without political reform. The historical record shows, however, that this is untrue. Over a period of many years, while their system of one-party rule was completely intact, the Soviet leaders tried all the reforms that the Chinese communists followed to revitalize their economy. This included several experiments with a household responsibility system, the so-called zveno, in agriculture (1933, 1947, and 1966); a regional decentralization (from 1957 to 1965); and several rounds of public sector reform (beginning in 1965), culminating in new laws to reduce the compulsory obligations on state-owned enterprises, allowing them to supply the market directly at higher prices (1987), and to permit private enterprise (1988).

In other words, rash political reforms are not the factor that decided why communism failed in Russia. The collapse of Soviet rule came only after the gradual economic reform initiatives that worked in China failed in Russia.

We must look somewhere else, therefore, to explain China's success. In a survey of Communism and Modernization, I suggest that the answer must begin with China's capacity for continuous policy reform. To break out of relative poverty and catch up with the world technological leader, an economy must undergo continuous reform of its policies and instutions. Continuous policy reform is fragile. The reason for its fragility is that, as the economy undergoes successive stages of modernization, policy reform at each stage must infringe upon the vested interests formed in the previous stage. Where continuous reform becomes blocked (as in Italy, for example), the economy will lag and fall behind. From the 1970s, the Chinese economy institutionalized a capacity for continuous policy reform. This is what has enabled China's spectacular rise.

Continuous policy reform was a by-product of China's system of "regionally decentralized authoritarianism" (described by Xu 2011). This system set China's 31 provincial leaders to compete with each other economically and also gave them considerable freedom to choose how to do so. Those leaders who could make their provincial economy grow faster, if necessary by attracting labour from neighbouring provinces, would rise politically; the laggards would fall. Such incentives were very strong.

Deng Xiaoping allowed the provincial bosses to strike a "China deal" that created new space for private business to come out of the cold and thrive within market socialism. This opening of markets to private entrepreneurs, modest at first, became much more radical than the limited "deals" struck in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. Economic reforms under European communism gave legitimacy, at most, to low-powered, short-term profit-based incentives, insider lobbies, and shady sideline trading networks.

In China the main limit that was placed on market access was political: China's new business class must continuously demonstrate its loyalty to the one-party state. The best way to prove loyalty was through political and family connections to the regime. This raised the danger of the new business class exploiting their personal links to power to grow rich without economic effort. One answer, but an imperfect one as we see today, was to expose them to foreign competition. In fact, there was more product market competition in export markets than across China's internal provincial borders.

A crucial and completely accidental advantage on China's side was its size. The Chinese population was so large that its 31 provinces each formed an economic region with tens of millions of people -- the size of a large Western European country. In contrast, the Soviet Union decentralized economic management across a much larger number of much smaller provinces, averaging little more than a million people each. Unlike a Chinese province, the typical Soviet province was highly dependent on its neighbours. The danger was that a Soviet provincial boss could gain more by sabotaging his neighbours than by honest effort within his own limited sphere. In the Soviet Union regional rivalry turned out to carry high costs and few if any benefits.

If regional rivalry was not productive within the Soviet Union, why did it not work across Eastern Europe as a whole? After all, each East European country had considerable freedom to experiment with national economic models, and was more like a Chinese province in size and diversity than a Soviet province. Nonetheless, international competition did not work any better than interprovincial rivalry. Most likely, East European communist leaders had too much job security and tenure, did not depend on doing better than their neighbours to keep their jobs, could not be promoted to Moscow, and, even if they succeeded economically, could not build on success to attract labour from their neighbours because international borders, even within the communist brotherhood of nations, were rigidly sealed.

It may also have been a factor that East European and Soviet leaders just did not "get" continuous policy reform. They thought catching-up growth could be achieved by one-off reforms or interventions. It is also a good question whether Chinese leaders "got" continuous policy reform, or whether they stumbled across a design for it by accident.

Either way, the result was this: The recipe that happened to make communism work in China was tried and did not work in Europe. That raises a question of vast proportions: Will the same recipe continue to work in China's future?

Here we come back to the fragility of continuous policy reform. China's level of output per head has multiplied several times over the level of the 1970s. It must multiply several more times before China can approach the level of the world's richest countries. This is a very long haul. For China to maintain the continuity of policy reform over the distance is beyond unlikely. At some point, some coalition of interests is bound to form that will be strong enough to block it, at least for a time. At that time China's oligarchy must be willing to intervene on the side of movement, not stability. If not, the China deal will come unstuck.

References:

Harrison, Mark. 2012. Communism and Economic Modernization. CAGE Working Papers no. 92. University of Warwick. Repec handle http://ideas.repec.org/p/cge/warwcg/91.html.

Xu, Chenggang. 2011. The Fundamental Institutions of China's Reforms and Development. Journal of Economic Literature 49:4, pp. 1076-1151. Repec handle http://ideas.repec.org/a/aea/jeclit/v49y2011i4p1076-1151.html.

June 29, 2012

Passing the Parcel: Who Will End Up Holding Europe's Democratic Deficit?

Writing about web page http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/knowledge/business/eurodead

It is widely thought that Europe has a democratic deficit (Follesdal and Hix 2006; The Economist 2012). This means that the European Commission and European Parliament exercise powers in the name of a European community and identity that do not really exist. In reality, these bodies are accountable only to national electorates. There are no true European parties, and national electorates make their choices on national, not European calculations. As a result, European institutions hold powers that are neither accountable nor legitimate. This is one source of the current crisis.

Since the Euro is unworkable in its current form, it must change. An interesting question is what will happen then to the existing democratic deficit. Whatever changes, the democratic deficit will not go away. Instead, it will be redistributed across the terrain of the Eurozone. Different upheavals will pass it around in different ways. Two scenarios illustrate the point.

- Scenario 1

If current proposals for a fiscal union across the present Eurozone are adopted, member states will lose much of their already limited sovereignty over public spending and taxes. Their remaining sovereignty will be pooled in Brussels and Strasbourg. Thus, the democratic deficit will continue to be Europe-wide.

Many citizens will get the feeling that the democratic deficit has widened, but this will be more apparent than real. The democratic deficit will be felt more, because its true scale will have been formalized in new unaccountable powers, whereas in the past the deficit was merely implicit in powers that were often deployed ineffectively. This feeling, however, will be particularly acute in the two poles of the Eurozone, Germany and Greece. This is because German voters will contribute most to the new fiscal transfers against their will, and because Greek voters will lose most sovereignty to new fiscal controls.

- Scenario 2

Suppose instead that one or more Club Med countries are ejected from the Eurozone, as may still happen. Provided the Euro itself survives, in the Eurozone core the democratic deficit should then shrink for two reasons. First, the required severity of new fiscal controls and the scale of new fiscal transfers within the Eurozone will be less, so Brussels and Strasbourg will acquire fewer new powers. Second, the sense of a shared European identity among the core countries may well be greater than at present, because the national electorates that remain will be those that feel more affinity with Germany.

Under this scenario the democratic deficit may shrink in the core of the Eurozone but expand in the countries that exit. Again there are several reasons. In theory, the exiting countries will regain sovereignty over their own affairs. In practice they will have less sovereignty even than now, because their financial systems and their international credit will have been wrecked in the process. As a result, their voters will face few, if any, good choices. In the face of national humiliation, the voters may well turn to anti-system, anti-democratic parties that will steal power first from the discredited democratic leaders, and then from the voters themselves.

In short, there do not seem to be any easy ways to make good the democratic deficit that has been built into European institutions. At best, all we can do is pass it round.

References

Economist, The. 2012. The Euro Crisis: An Ever Deeper Democratic Deficit. The Economist, May 26. Weblink: http://www.economist.com/node/21555927.

Follesdal, Andreas, and Simon Hix. 2006. Why There is a Democratic Deficit in the EU: A Response to Majone and Moravcsik. Journal of Common Market Studies 44:3. pp. 533-562. Repec handle: http://ideas.repec.org/p/erp/eurogo/p0002.html.

May 28, 2012

Seventy Years Ago: The Week the Tide Began to Turn

Writing about web page http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/events/wwii-pac/midway/midway.htm

Seventy years ago this week, the world looked unspeakably grim.

By the end of May 1942, Germany had occupied France, Belgium, Netherlands, and Luxemburg; all of Eastern Europe not already under control of its allies Bulgaria, Hungary, and Romania, including the Baltic, the Ukraine, and a large chunk of Russia; Greece and Yugoslavia; and the former Italian colonies of North Africa. Italy wasn't helping much, but in the Far East Japan had occupied much of China, all of Indochina, Indonesia, Malaya (including Singapore), the Philippines, and part of Burma. German bombers were battering Britain's cities; German submarines were sinking Allied shipping at half a million tons a month. In Russia and Ukraine the German Army was launchng new offensives; at Khar'kov, in a battle that ended seventy years ago today, the Red Army lost a quarter of a million men. Across Europe and East Asia, millions of non-combatants were being machine-gunned, gassed, starved, and worked to death.

At this very moment, beneath the surface of these terrible events, the tide of the war was beginning to turn. Up to that time, Axis forces were advancing on all fronts. Within a few months they were in retreat everywhere.

In 1942 the war was fought in three main theatres: the Pacific, the Mediterrean, and the Eastern front. In each theatre the turning point of the war was marked by a decisive battle. These were the Battles of Midway (June 4 to 7), the seventieth anniversary of which we are about to mark; El Alamein (July 1 to 30 and October 23 to November 4); and Stalingrad (September 13 to February 2, 1943).

In obvious ways these battles could not have been more different: Midway in the remote northern Pacific, Alamein in the desert sands of Egypt, and Stalingrad in the smoking ruins of a great city on the Volga river. These battles differed also in the orders of magnitude of the forces involved. Japanese losses in four days at Midway were five ships, 250 aircraft, and 3,000 men. German losses in two weeks at the second battle of Alamein were 800 tanks and guns and 30,000 men, and in five months at Stalingrad 7,500 tanks and guns and three quarters of a million men killed or missing. Red Army losses at Stalingrad alone were half a million; do not forget these figures if you want to understand how powerfully the war continues to stir national feeling in Russia.

In other respects, these battles had important common features. Each began with an enemy offensive. The Japanese planned to use Midway Island as a launching pad from which to invade Hawaii. The Germans planned to drive the British out of North Africa; if the Mediterranean could not be an Italian lake, then let it be a German one. From Stalingrad the Germans planned to seal off the Caucasian oilfields and turn north to take Moscow from the rear.

After the offensive came the counter-offensive, which in each case took the enemy by surprise. After the successful surprise attack on the U.S. Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the Japanese believed they had finished American naval power. Just six months later, in the summer of 1942, the U.S. Navy was already three times the size of the previous year. Such was the speed of mobilization of America's industrial power, and the resilience of American national feeling, both of which had been entirely discounted in Tokyo and Berlin. The same underestimation of Allied reserves was present in the calculations of the Axis commanders at Alamein and Stalingrad.

The Allied victories of 1942/43 were no accident. Underlying them was the translation of Allied economic power into fighting power. In 1941 the Axis Powers were poised for victory. But victory would be theirs only if they exploited the advantage of the aggressor to the full. With a potential coalition of economically more powerful enemies ranged against them, they had to win every campaign quickly and avoid a stalemate at all costs. Had they done so, the war would have been over and they would have won.

Economic mobilization, the translation of economic power into fighting power, takes time. The Allies bought this time with "blood and treasure." First came the British refusal to surrender in the summer of 1940, followed by the Battle of Britain. Next came the U.S. Lend Lease Act of March 1941 which offered American aid to the British (and a few months later to the Soviet Union). The third thing was the unexpected -- in German eyes, often senseless -- resistance of the Red Army in the summer and autumn 1941, which led through appalling losses to the failure of the German invaders to take Leningrad and Moscow before the end of the year.

Source: Harrison (1998, pp. 15-16).

Having bought time, the Allies used it to mobilize their economies. The chart shows the production of combat aircraft by the main powers year by year through the war. It illustrates how, during 1942, Allied -- and especially American -- mobilization rapidly tilted the military-economic balance against the Axis. The Allies began to outproduce Germany and Japan in aircraft, and also in munitions generally, by a substantial multiple. This advantage persisted through the end of the war, despite belated mobilization of the German and Japanese war economies. In 1942, however, the grit and bloody determination of Allied soldiers, sailors, and airmen was still required to turn material predominance into victory on the battlefield. Midway, Alamein, and Stalingrad were the signals that this had been achieved.

Why was the struggle so much, much more intense on the Eastern front? From mid-1941 through mid-1944 this was where 90 percent of German fighting power was focused. To occupy the territory of Ukraine and European Russia, kill the Jews, decimate the Slavic population, and resettle this vast landmass as a German colony, was Hitler's prime objective. The Soviet economy, although large, remained poor and industrially less developed, so that it was on the Eastern front that German resources were most evenly matched. The Allies' material advantages were much greater elsewhere. If the Axis could not win in Russia, it would not win anywhere else. On the Eastern front a war of mutual annihilation developed, in which both sides threw everything they had and more into the scales. As I discussed in a paper entitled "Why Didn't the Soviet Economy Collapse in 1942?" (Harrison 2005), Hitler had every right to expect final victory. The Soviet Union only just managed to retain a critical advantage over Germany, based on mass production, colossal sacrifice, and utter ruthlessness.

Up to the summer of 1942, the forces of the Axis were advancing everywhere; from the beginning of 1943 they retreated on all fronts. After this it was no longer possible for the Axis powers to win the war against the economically more developed, more mobilized, and more powerful Allies. One of the most horrifying faces of the war is seen in the fact that, despite this, years of intense fighting still lay ahead. Through 1943, 1944, and into 1945 the German and Japanese Armies and Navies retreated continuously, killing and being killed every day and every inch of the way, maintaining discipline and cohesion, not giving up until the last possible moment. Every day of those years their governments persisted in genocidal policies that destroyed millions of lives through famine, overwork, and systematic mass killing.

Without Midway, Alamein, and Stalingrad our world today would be far different from the one we know. The Axis powers might have ended the war victoriously, with consequences that we can only guess at. Alternatively, the war would have been dragged out in some other way, but there would have been no Allied victory in 1945. Or perhaps there could still have been victory in 1945, but the evolution of events would have been entirely different. Regardless of events on the battlefield, by the summer of 1945 the Americans would have had the atomic bomb. If the war still raged in Europe, the first victims of atomic warfare would more likely have been German than Japanese.

References

- Harrison, Mark. 1998. Economic Mobilization for World War II: an Overview. In The Economics of World War II: Six Great Powers in International Comparison, pp. 1-42. Edited by Mark Harrison. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Harrison, Mark. 2005. Why Didn't the Soviet Economy Collapse in 1942? In A World at Total War: Global Conflict and the Politics of Destruction, 1939-1945, pp. 137-156. Edited by Roger Chickering, Stig Förster, and Bernd Greiner. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. RePEc handle: http://ideas.repec.org/p/wrk/warwec/603.html

May 23, 2012

Greece: Can’t Pay/Won’t Pay?

Writing about web page http://www.erim.eur.nl/ERIM/Research/Centres/Business_History/News/News_Detail?p_item_id=7362016&p_pg_id=

How much can one country squeeze out of another? I was prompted to think about this on Monday, when I spoke in Rotterdam at the launch of a major new book: Occupied Economies: An Economic History of Nazi-Occupied Europe, 1939-1945, by Hein Klemann (a Dutch historian) and Sergei Kudryashov (a Russian historian).

The main story of the book is how Germany extracted resources from occupied Europe that paid for one third of its war costs – and the consequences for the countries that paid. When you read history, it’s natural also to think about the present: what has changed, and what is the same. So, I thought about Greece.

Seventy years ago, Greece was under German occupation. Between 1942 and 1944, according to Klemann and Kudryashov, Germany took from Greece goods and services worth 3.5 billion Reichsmarks. Per head of the Greek population, this was between RM500 and RM600 per head, which was about the average for Germany’s occupied territories.

That sounds like a lot, but what did it mean to Greece? The back of my envelope shows the following calculation. In 1942, Germany imported external resources worth about 15 per cent of its national income. Klemann and Kudryashov show that Greeks were average contributors. Before the war, Greece’s national income per head of its population was about half Germany’s. So, a sum that in wartime was worth 15 per cent to Germans was worth at least 30 per cent to Greeks. Given Germany's wartime economic expansion, and the likely economic decline of Greece, I guess the upper limit could easily have been half of Greece’s national income in 1942 and 1943.

The point is that Germany’s wartime exploitation of occupied Europe was a very big deal, and Greece was no exception.

Now roll the clock forward seven decades. Look how the scenery has changed. The world is relatively peaceful and world markets are open for business. In Greece, average real incomes are six times the level of 1938. But Greeks are smarting under the national humiliation of being expected to pay for their public debt. Eighty per cent of that debt is held abroad, a large share of it by Germany. But the debt is an obligation that Greece assumed completely voluntarily. The Greeks are not under duress of any kind; the creditors have placed no landing craft on Greek beaches; in Kefalonia, no villagers are held hostage, and no Athenian commuters must show their papers at military checkpoints.

Still, the Greek sense of victimhood is so strong that they are not actually repaying anything at all. Instead, their government is continuing to borrow on the basis of being granted partial forgiveness. The fact that eighty per cent of Greek debt is held abroad implies that Greece should be exporting more than it imports if it wants just to cover the interest on the debt that remains. This year Greece's current account deficit is expected to be 5 per cent of its GDP, so that Greek foreign liabilities are rising, not falling. Meanwhile there is a political stalemate, and the anti-bailout parties (which together form a majority) argue they can slow or reverse the fiscal consolidation required to reduce the rate of new borrowing while keeping the creditors and the European Commission on board and disagreeing with each other about everything else.

Economic history suggests that it is exceptionally difficult to persuade a country to hand over a significant fraction of its national income to foreigners over any sustained period of time. Naked force will do the trick, but nothing less will do.

Today Germany is Europe's creditor. Writing in the Financial Times, my Warwick colleagues Marcus Miller and Robert Skidelsky recently (2012) drew a parallel with Germany's own experience after the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. Victorious in the Great War, the Allies imposed a large war indemnity upon Germany. This was mainly counterproductive, arousing German national feeling and resistance to the peace with regrettable consequences.

How much did the Allies actually extract from the German economy under the reparations imposed at Versailles? The accounting comes from a classic paper by Sally Marks (1978). The treaty’s headline figure was 132 billion gold marks, around two and a half times Germany's prewar national income. Of the 132 billion total the Allies themselves never expected to get more than 50 billion (the so-called A and B bonds). Germany paid a first instalment right away by handing over state properties valued at 8 billion; today's analogue might be the transfer of a few Greek islands. Germany paid the next billion in 1921 to get the Allies out of customs posts and an area around Dusseldorf that they continued to occupy. Then, the repayments stopped. In response the French occupied the Ruhr valley in 1923, netting another billion in compulsory deliveries of coal and other stocks. When the French moved out, payments fell away again and were repeatedly rescheduled. At their termination by the Lausanne Convention in 1932, Germany had paid barely 20 billion marks in total. In practice, most of that sum was borrowed from the United States, creating new debts on which Hitler later defaulted. Marks concluded:

The tangled history of reparations remains to confound the historian and also to demonstrate the futility of imposing large payments on nations which are either destitute or resentful and sufficiently powerful to translate that resentment into effective resistance.

Note the terminology, which we'll come back to. "Destitute" = "Can't pay." "Resentful and ... powerful" = "Won't pay."

By modern standards, the Allied occupation of Germany's revenue offices and valuable territories after the Great War looks like an intolerable infringement of national sovereignty. In fact there were many precedents for this, which the Allies merely followed. A recent paper by Kris Mitchener and Marc Weidenmier (2010) analyses 43 such cases from the nineteenth century. Today Greek opinion is inflamed by the idea of a European Commission representative in its budget office; Athens last came under foreign financial supervision in 1898, having defaulted on an indemnity arising from war with Turkey the previous year.

Based on this and other cases, Mitchener and Weidenmeier show that "supersanctions," when the creditor countries applied direct military pressure or directly supervised the debtor's fiscal offices, generally sufficed to restore the debtor's credit by enough to reduce bond yields and allow access to fresh borrowing.

What creates the power of sovereigns to resist their creditors, if direct force is not applied? Writing during the last major international debt crisis, Simon Bulow and Ken Rogoff (1989) argued that sovereign debtors are able to play on their creditors' impatience and desire to rescue something from the situation; faced with the threat of complete default and the need to apply draconian penalties, the creditors will be satisfied with partial compliance. The debtors will pay just enough to keep open their access to fresh borrowing.

The result is the phenomenon of continual rescheduling clearly visible in recent renegotiation of the Greek debt. Indeed it would seem that no one has read Bulow and Rogoff more carefully than Alexis Tsipras, leader of Greece's largest anti-bailout faction, the left-wing Syriza Party.

Despite partial default and bailout, Greece remains insolvent. Strictly interpreted, insolvency means that the debtor cannot pay. But the history of sovereign debt and default tells us that “Won’t pay” and “Can’t pay” are hard to tell apart, and it is in the debtor’s interest to make them look the same.

Allied failure to predict and manage this after World War I helped to poison Germany’s international relations and domestic politics in the 1920s. Miller and Skidelsky argue that Germany, which suffered so much after 1919, should not do the same to Greece today. I agree. But a far sighted reconciliation does not look likely, and might not even by welcomed by those Greek politicians who are now happily reinventing the tradition of Greece as a victim of foreign exploiters.

References

- Bulow, Jeremy and Kenneth Rogoff. 1989. A Constant Recontracting Model of Sovereign Debt. Journal of Political Economy 97:1, pp 155-178. RePEc handle: http://ideas.repec.org/a/ucp/jpolec/v97y1989i1p155-78.html

- Klemann, Hein, and Sergei Kudryashov. 2012. Occupied Economies: An Economic History of Nazi-Occupied Europe, 1939-1945. London: Berg. Weblink: http://www.bergpublishers.com/?TabId=15036

- Marks, Sally. 1978. The Myths of Reparations. Central European History 11:3, pp. 231-255.

- Miller, Marcus, and Robert Skidelsky. 2012. How Keynes Would Solve the Eurozone Crisis. The Financial Times, May 15. Weblink: http://www.ft.com/cms/s/2/55d094cc-9e74-11e1-a24e-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1vF2uhjh4

- Mitchener, Kris, and Marc Weidenmier. 2010. Supersanctions and Sovereign Debt Repayment. Journal of International Money and Finance 29:1, pp. 19-36. RePEc handle: http://ideas.repec.org/a/eee/jimfin/v29y2010i1p19-36.html

May 14, 2012

The Dam Busters: Their Place in (Economic) History

Writing about web page http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/knowledge/culture/dambusters

Written for Warwick's Knowledge Centre in preparation for Wednesday night's sixty ninth anniversary of the dam raids.

The dams of Germany’s industrialized Ruhr valley were an obvious target for the Royal Air Force Bomber Command in World War II. The dams supplied hydroelectric power and water for cities, steel making, and canal transport. In turn, these provided the means to supply Germany with the tanks, aircraft, guns, shells, and ships required for Hitler’s war.

Operation Chastise, the Dam Busters’ raid, took place on the night of May 16/17, 1943. Tactically, it was a partial success. The Möhne and Eder dams collapsed, but the Eder reservoir was of secondary importance and the dam on the Sorpe was not seriously damaged. Some small towns and industrial facilities were flooded, and some roads were washed away. There was a temporary loss of water production and electric power. At least 1,300 civilians died; more than half were Ukrainian forced labourers. Eight of the 19 aircraft were lost and 53 of the 133 aircrew killed.

What were the effects of the dam raids on Germany’s war economy? From the beginning of 1942 through May 1943, German war production expanded at about 5 per cent a month. At the time of the dam raids it was already more than twice the level of two years previously when Germany had been about to launch the greatest land invasion of all time, its attack on the Soviet Union. In the month of the dam raids, however, the increase of German war production was halted and the German economic mobilization marked time for nearly a year.

How much of this was due to the Dam Busters? In 1943 British and American bombers dropped 130,000 tons of bombs on German cities and factories, and ten times that quantity in 1944 (Zilbert 1981). Up to a million German civilians lost their lives (Falk 1995). In this context the dam raids were a pinprick. Thus, while the raid was mounted at an important moment, it would be hard to identify any particular effect of the Dam Busters’ skill and heroism on the German war effort.

The dams were quickly rebuilt and water supplies were restored. Were these indirect costs important? Albert Speer, the minister of armament, had to divert 7,000 forced labourers from building German fortifications in occupied France and Netherlands to rebuild the dams (Speer 1970, p. 281). It has been suggested that this contributed to Allied success in the 1944 D-Day landings (McKinstry 2009), but the claim seems far-fetched. In May 1943 the Germans still had a year to complete their coastal fortifications. Much more important to Allied success on D-Day were numbers, surprise, and the German lack of air cover.

When Operation Chastise was planned, RAF Bomber Command did not take into account either D-Day or the indirect cost to Germany of diverting scarce labour from the fortification of occupied Europe. In fact, the RAF hoped to bomb Germany into defeat before D-Day became necessary. In this way, the operation expressed the persistent belief in a powerful knock-out blow that would somehow disable the German war economy and deprive its armed forces of the means to fight. Somewhere, they thought, if only it could be found and attacked, was a critical weak point of the German war economy that could cause it to collapse. Perhaps the dams were such a weak point.

Speer later suggested that the direct effects of the raid would have been greater if the RAF had organized follow-up raids to disrupt the rebuilding. But the lack of follow-up also expressed the mistaken belief of the time in the efficacy of a single knock-out blow. Two centuries of experience of economic warfare and sanctions (summed up by Olson 1963) have taught us that this belief is generally unfounded.

Bombing Germany did not win the war, but it did bring forward the moment of German defeat. Bombing was highly disruptive and made mobilization ever more costly (see Overy 1994 and Tooze 2006). For a long period the German leaders were able to restrict the consequences to the civilian economy, so that conditions of life, consumption, and work deteriorated but war production could still expand. Civilian life was maintained by the human capacity for adaptation to difficulties and habituation to fear. Disaffection was kept in check by an effective police state, growing hatred of the Allied bombers, increasing awareness of Germany’s own war crimes, and rising fear of the possible consequences of defeat. Requisitioning food and slave labourers from the occupied territories also helped. That was the basis on which Germany was able to fight on against economically more powerful enemies for years.

Only when German territory was directly attacked did the war economy finally unwind. The indirect effects of Allied bombing also helped to bring that moment nearer. Allied bombing weakened the German ground forces because it distracted German air power away from the Eastern Front (against the Red Army) and France (against the 1944 Allied landings). Defending against air attack was very costly for Germany. At the peak of war mobilization, one third of German war production took the form of night fighters, anti-aircraft guns, searchlights, and radar.

Bombing Germany was costly to both sides. On one side the German economy was disrupted and a million civilians died. On the other side 18,000 Allied bombers were lost, along with 100,000 highly trained and educated aircrew.

The Dam Busters were one small element of a total war. They did not provide a breakthrough, but they added to the slowly growing burdens on the German economy, which arose through channels that were largely unintended and unforeseen. The Dam Busters also boosted Allied morale and Churchill’s status with the Americans and the Russians. Without them, the book (Brickhill 1951) and the film of the book could not have been made. These gave a sense of heroism and past glory to many a British schoolboy. I don’t know what the girls thought; we never asked them.

References

- Brickhill, Paul. 1951. The Dam Busters. London: Evans.

- Falk, Stanley L. 1995. Strategic Air Offensives. In The Oxford Companion to the Second World War, pp. 1067-1079. Edited by I. C. B. Dear. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Milward, Alan S. 1965. The German Economy at War. London: Athlone.

- McKinstry, Leo. 2009. “Bomber Harris thought the Dambusters’ attacks on Germany ‘achieved nothing’.” The Telegraph, August 15.

- Overy, Richard J. 1994. War and Economy in the Third Reich. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Speer, Albert. 1970. Inside the Third Reich. London: Macmillan.

- Olson, Mancur. 1963. The Economics of the Wartime Shortage. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Tooze, Adam. 2006. The Wages of Destruction: The Making and the Breaking of the Nazi Economy. London: Allen Lane.

- Zilbert, Edward R. 1981. Albert Speer and the Nazi Ministry of Arms: Economic Institutions and Industrial Production in the German War Economy. London: Associated University Presses.

Mark Harrison

Mark Harrison

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…