All 61 entries tagged Economics

View all 245 entries tagged Economics on Warwick Blogs | View entries tagged Economics at Technorati | There are no images tagged Economics on this blog

June 13, 2014

The military power, economics and strategy that led to D–Day

Writing about web page http://theconversation.com/the-military-power-economics-and-strategy-that-led-to-d-day-27663

The Conversation published this column on the seventieth anniversary of D-Day, June 6 2014. I thought I'd include it here.

On June 6, 1944, more than 150,000 Allied troops landed in Normandy. Their number rose to 1.5m over the next six weeks. With them came millions of tons of equipment, ranging from munitions, vehicles, food, and fuel to prefabricated floating harbours.

The achievement of the Normandy landings was, first of all, military. The military conditions included co-operation (between the British, Americans, and Free French), deception and surprise (the Germans knew an invasion was coming but were led to expect it elsewhere), and the initiative and bravery of officers and men landing on the beaches, sometimes under heavy fire. More than 4,000 men died on the first day.

D-Day was made possible by its global context. Germany was already being defeated by the Soviet Army on the eastern front. There, 90% of German ground forces were tied down in a protracted losing struggle (after D-Day this figure fell to two-thirds). The scale of fighting, killing, and dying on the eastern front was a multiple of that in the West. For the Red Army in World War II, 4,000 dead was a quieter-than-average day.

Economic factors were also involved. In 1944 the main fighting still lay in the east, but the Allied economic advantage lay in the west. Before the war the future Allies had twice the population and more than twice the real GDP of the Axis powers. During the war the Allies pooled their resources so as to maximise the production of fighting power in a way that the Axis powers did not attempt to match. America made the biggest single contribution, shared with the Allies through Lend-Lease.

Between 1942 and 1944 Allied war production exceeded that of the Axis in every category and on all fronts. This advantage was especially great in the West. In the chart below, a value of one on the horizontal plane would mean equality between the two sides. Values above one measure the Allied dominance:

Eventually the accumulation of firepower helped turn the tide. A German soldier in Normandy told his American captors, “I know how you defeated us. You piled up the supplies and then let them fall on us.”

D-Day was made possible by economics, but it was made inevitable by other calculations. When the outcome of the war was in doubt, Stalin demanded the Western Allies open a “second front” in Western Europe to take pressure off the Red Army. At this time, working towards D-Day was a price that the Allies paid for Stalin’s cooperation in the war. By 1944 German defeat was assured; now D-Day became a price the Western Allies paid in order to help decide the post-war settlement of Europe.

While D-Day was inevitable, its success was not predetermined by economics or anything else. The landings were preceded by years of building up men and combat stocks in the south of England, and by months of detailed logistical planning. But most of the plans were thrown to the wind on the first day as the chaos of seasick men struggling through the surf and enemy fire onto the Normandy sands unfolded. This greatest amphibious assault in history was a huge gamble that could easily have ended in disaster.

Had the D-Day landings failed, our history would have been very different. The war would have dragged on beyond 1945 in both Europe and the Pacific. Germany would still have been undefeated when the first atomic bombs were produced; their first victims would have been German, not Japanese. Germany and Berlin would never have been divided, because the Red Army would have occupied the whole country. The Cold War would have begun with the Western democracies greatly disadvantaged. We have good reason to be grateful to those who averted this alternative history.

![]() Mark Harrison does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

Mark Harrison does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

May 22, 2014

Gas and Geopolitics

Writing about web page http://www.energylivenews.com/2014/05/22/china-russia-gas-deal-solves-both-their-problems/

China and Russia (represented by the Russian state oil major Gazprom) have signed a deal that will supply China with gas worth up to $400 billion over 30 years. Since Energy Live News and International Business Times have quoted my views, I thought I'd put up the full version, which goes like this:

For China the Gazprom deal solves an energy problem. For Russia, it solves a market problem: Russia needs to sell its energy sources somewhere, but has spoiled its traditional market among the European democracies to Russia’s south and west by applying economic and military coercion to Ukraine.

Both China and Russia are governed by authoritarian regimes. Major bilateral trade deals among such regimes have a long history. Exactly what they mean depends greatly on context, sometimes unpredictably so. In the late 1930s Hitler encouraged bilateral trade deals between Germany and countries to Germany’s east not out of friendship, but because he considered them to be part of Germany’s future colonial sphere. Most notorious of these was the German-Soviet trade deal associated with the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact of 1939, which was followed within two years by all-out war. After World War II Stalin deliberately fostered bilateral trade deals between the Soviet Union and countries like Poland and Hungary in order to tie them into the Soviet economic sphere; for the same reason he prevented them from making bilateral deals with each other. These deals were followed by closer integration, not conflict.

No one envisages war between Russia and China, but it is important to remember that ultimately the governments of these two countries see each other as rivals in the global balance of power. China’s population and wealth are rising faster than Russia’s; Russia remains an Asian power, but the balance of power in Asia is moving steadily against Russia. Smiles around the table in Beijing do not betoken true affinity.

As authoritarian rulers (and the commercial entities under them, like Russia’s Gazprom) approach bilateral deals, they have an advantage and a problem. The problem is that everyone understands the signatories are not necessarily the real principals. The real principals are Russia’s Vladimir Putin and China’s Xi Jinping. No court will punish either of them if one of them chooses to break the Gazprom contract in future. The advantage they have is over open societies, where public opinion counts. In an open society, public distaste can sometimes get in the way of business. No human rights issues are likely to derail the China-Gazprom deal.

March 24, 2014

Marxism: My Part in Its Downfall

Writing about web page http://warwick.ac.uk/markharrison/comment/economics_of_capitalism_ver_2.pdf

The news has been so grim on many fronts that I begin to long for something a little lighter. To help things along, here is a story I began to write a long time ago, but never finished until now. It tells how it happened that in 1976 I published a 20,000-word pamphlet called The Economics of Capitalism.

Another stimulus to go back to this was that I got drawn into a discussion about Marxian economics. Not everyone with whom I was debating with would give me credit that I knew much about Marxism in the first place. In that context I mentioned that one day I intended to put my pamphlet on line. Now, here it is -- in two versions. One is the original, scanned as images(therefore large: 30Mb). The other is OCR'd and so 99 per cent searchable(much smaller: 4Mb). (Or, if you insist, a few copies are still available in the second-hand market.)

In the searchable version I've taken care to conserve the original illustrations and page layout. The illustrations were by Richard Hill, whom I never met, so I never got around to telling him what I thought of them. Are you out there, Richard, or anyone who knows you? I just loved the illustrations as soon as I saw them, and I still do.

The origins of the pamphlet were like this. I joined the communist party in 1973. This was for reasons I've discussed elsewhere so I won't go into them here. I was soon drawn into various activities as a student and then as a young lecturer. It wasn't long before I met Betty Matthews, who ran the communist party's education department. This meant she was responsible for producing education material for the party members and their branches.

I certainly wasn't the party's only economist. Others, such as Maurice Dobb and Bob Rowthorn (Cambridge), Ron Bellamy (Leeds), and Pat Devine and Dave Purdy (Manchester) were of longer standing and greater eminence. Dobb was a world-famous scholar. I recall that the party had an economic advisory committee to consider its economic policies. I wasn't a member of that, and I've no idea who was on it, but probably some of these. Anyway, unlikely as it might have seemed at the time, somehow or other I was the one Betty persuaded (or maybe I was the one who offered) to write an economics pamphlet for the purposes of party education.

The previous material that was out there for party members was Sam Aaronovitch's Economics for Trade Unionists, published in 1964. In its time this was a solid introduction, and Sam was a good scholar, but Betty felt it needed updating. So I got to work and The Economics of Capitalism was the result. If you read the acknowledgements, you'll see I had some help, with comments and advice from Pat Devine (see above), from Betty Matthews and Bert Ramelson (see below), and also from Keith Cowling and Ben Knight who were sympathetic colleagues at Warwick. I remain grateful to all these people.

I'd like to break the narrative for a moment to say how much I valued getting to know Betty and meeting and talking with her (and her assistant Deanna, whose family name I've forgotten). Betty always seemed like a thoroughly cheerful person and a kind soul. According to Sarah Benton's obituary she was "unique in the communist world in having no enemies." I'm not surprised. Betty spent her childhood in Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe). I'd recently read Doris Lessing's account of a similar childhood. Lessing was sent to church, where the message was brotherly love, and then came out and saw the hypocrisy of the colour bar. She decided that the colour bar must be wrong. I asked Betty if her experience was the same. She laughed and said: "Oh, no. I decided that the church must be rubbish!" Anyway, I thought Betty was a good person and that made her hard to refuse.

As for the substance of what I wrote in the pamphlet, I'm not going to review my own work here. Anyone can read it and decide what they think for themselves. I'm just going to comment on a couple of aspects of the writing. One is about the history in it; the other is about the party and its sensitivities.

First, the history. One question I've sometimes asked myself is: Where on earth did I get the history from? There was a lot of freedom in writing without footnotes, and I am not sure I used that freedom wisely. When I re-read what I wrote then, the history now seems pretty slapdash to me. Probably it was a mishmash of stuff I half understood and borrowed from Dobb, Rodney Hilton, E. P. Thompson, and a few others that I've forgotten. They might not appreciate what I did with their work. I'm pretty sure that today I'd follow a different style of writing, with more respect for facts, including the ones that did not fit. Nowadays even my lecture notes have footnotes for everything.

In contrast to my cavalier approach to history, I tried to be careful with the economic facts. I even put in a statistical appendix.

Second, the party. As a young party member, and at the same time a professional scholar, I was always watchful and curious to find out whether at any point the party would start telling me what to write. I didn't know how I would react if that happened. I felt a commitment to the truth. I felt a commitment to the cause. Politics being what it was, I half expected that at some point these two commitments might clash, and I did not know how I would manage it if that came.

As it turned out, the only aspect of the pamphlet that anyone in the party (other than an economist) really cared about was how it would explain inflation and the role of trade unions. This was bitterly controversial in British society in the 1970s, and the issue was contested within the labour movement and even within the communist party.

Since the 1950s, successive British governments had taken the view that the cause of rising inflation was increases in wage costs, which arose from the excessive wage demands lodged by the trade unions. The appropriate remedy to inflation was therefore wage controls, voluntary or statutory. In recognition that wages were not the only cost of production (although the largest proportion in the economy as a whole), this became known as "incomes policy." From the 1950s through the 1970s, successive governments tried and failed to use incomes policy to control inflation.

At the time I was writing, the British economy was experiencing its greatest inflationary crisis. We didn't know it yet, but it would pave the way to Margaret Thatcher's historic 1979 election victory. Trade union power and wage pressure were huge issues. The "official" position of the communist party at the time, as far as I recall, was that inflation hurt the workers, but wage pressure was not the cause of inflation. A class struggle was in progress in which the organized workers were fighting the employers using the weapon to hand: wage demands, backed up by strike action. Price-setting was the weapon in the hands of the capitalist employers, so inflation was the counter-attack of the capitalist class. Anything that weakened wage pressure favoured the enemy.

This line was much debated. I've probably forgotten a lot of nuances that were important to others, so I'll speak for myself. My own view was something like this: There was a distributional struggle in progress. Suppose the initial distribution of the national income between wages and profits was 70 per cent to 30. The workers wanted to increase their share at the expense of the employers, and would try to achieve this by pushing up nominal wages. The capitalists wanted to raise profits at the expense of the workers, and would aim to achieve this by raising prices. As a result, the implicit claims on the national income would exceed 100 per cent. The workers wanted 75 and the employers wanted 35. If you added up 75 and 35 the sum was 110 percent, so the outcome would be 10 per cent inflation -- a self-defeating wage-price spiral.

Put like that, it was a non-monetary theory of inflation. Nowadays absolutely nobody believes you can understand inflation without thinking about money. Even then, the party's economists had surely all read Milton Friedman, who told us that inflation was "always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon." While we didn't buy this completely, we understood that inflation had to have a monetary dimension. For myself, I thought that the inflation process was contingent on some sort of government commitment to full employment. This was the commitment that enabled workers and employers to push up their incomes against market pressure. A later generation would call this the "soft budget constraint," a term that Janos Kornai developed to analyze Soviet-type economies. In capitalist Britain, the soft budget constraint meant was that the government's fiscal and monetary policies were being relaxed continuously to maintain real demand and keep down real interest rates, and this would also be an essential permissive condition of the inflationary process.

In the trade unions, many communists were not particularly keen on this line of argument. It seemed to give away too much to the idea that trade unions caused inflation. They wanted to say that the capitalist class was on the offensive and the wage struggles of the time were basically workers' self-defence. In other words it was capitalism that caused inflation, not the workers. In my view, even at the time, this was somewhat implausible. The share of profits in British GDP had been declining since the 1950s (and the contribution of domestic trading profits had fallen even faster) so wage militancy looked more offensive than defensive. On that basis, it was very hard to maintain that trade union militancy was not at all complicit in the inflation of the time.

In this context, there was a lot of focus on what my pamphlet should and shouldn't say about inflation. Betty Matthews told me I had to meet Bert Ramelson and talk it through with him. Bert ran the communist party's industrial department. He had played a key role in many episodes of the struggle of Britain's organized workers, most famously the seamen's strike of 1966 and the miners' strike of 1972. The last thing he and other communists involved in the trade unions wanted was that a publication by the party's own education department would be quoted in the media saying that striking for higher wages would end up hurting the workers.

My one and only meeting with Bert took place in Coventry railway station where we talked over a cuppa in the cafeteria off platform 1. I was nervous about it. Bert was a legend of the labour movement; I was a nice middle-class boy who had never done anything much outside school and college. I had the academic qualifications, but Bert had the steel that was tempered in the furnace of the class struggle. I could not anticipate how he would respond to me; I did not know what criticisms he might have, and I did not expect he would swallow them easily.

In fact, our conversation was amicable. I had insured myself to some extent by being even-handed: I wrote in the pamphlet that the causes of inflation were controversial, and I outlined various perspectives, and I suggested that they all contained some unspecified measure of truth. I also wrote that wage militancy was not enough to transform society; this was something that no one would have disagreed with, even then, although there would have been a lot of dispute over how and by how much it fell short. There were certainly those party members that behaved as if they believed wage militancy was 99 per cent of the revolutionary struggle -- at least.

Bert turned out to be concerned more with what I would write about the future of trade unionism than trade unions in the present. Tighter restrictions on trade union rights were in the air. The party was opposing them vigorously. In order to give credibility to the party's defence of unfettered trade union rights in the present, it was also party policy to promise that trade unions would continue to be free and independent, with entrenched rights, in the transition to socialism. Bert wanted me to make this clear.

The result was a passage that read:

Our path will encounter many problems. For example, in the process the state must acquire far more power than ever before. But we seek power for all working people, not for bureaucrats and civil servants. And in fact the struggle for democratic rights is an integral part of challenging the state power of monopoly and ultimately replacing it. Thus if the outcome is to mean more democracy, and not just more bureaucracy, the autonomy of the working class, and of its sectional mass organisations the trade unions, and of its allies, must be strengthened and extended. That is why the freedom of collective bargaining today is a guarantee for tomorrow.

For example, in a socialist economy, for the progress of society as a whole, one group of workers or another may sometimes have to be asked - not ordered - to moderate wage demands, or change jobs. But in a socialist state, for the first time, these processes will be open and subject to democratic control.

Today it may read like wishful thinking. It didn't at the time. at least, not to me; there was nothing there that it was hard for me to sign up to. Bert had been persuasive but not heavy handed or confrontational; he treated me very correctly and I did not feel that I had compromised anything in writing those words. Just in case, however, I concluded with a libertarian flourish:

The most important of society’s productive forces is the working class itself. The British working class today has skills, understanding and aspirations available to it as never before. Capitalist relations today hold back its development, and face it with low wages and stultifying labour discipline at work as the only alternative to unemployment. Beyond it lies the vision of a world in which “the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all”.

Anyway, the pamphlet was finished, went to the printer, and came out. I was very proud of it (and delighted by the illustrations, as I've said). What impact did it have? I've absolutely no idea. Looking back, I think it's remarkable (and not in a good way) that I never had any idea of how many were printed or sold or how widely it was used for its intended purpose, that is, for discussion as educational material. I think I did one or two meetings around the Midlands, based on the pamphlet, but that was all. For all I know, the rest of the stock was packed up and warehoused, or sent out to the branches where it was stored in cupboards up and down the country, and finally ended up in a hundred skips when the party branches closed down.

There's a final question that I'll pose: What would have happened to the British economy if that party programme had been implemented? It's not a completely idle question. In 1976 the late Tony Benn, then a government minister, put something pretty similar to the British cabinet as an alternative to the IMF loan that Denis Healey was after. It was rejected -- but what if it had been put into effect? How would the economic effects have worked out? Not well, I now imagine. Most likely the experience of Belarus or Venezuela would give a few hints.

The moment when my pamphlet appeared, as it happens, was just about the peak of popularity of Marxian economics in the English-speaking world. After that, everything went downhill. This should not be a surprise because the world of the 1970s was about to move strongly to the right. In 1979 Margaret Thatcher became British prime minister, and in 1980 Ronald Reagan was elected US president. Everyone moved on, including, eventually, me.

To prove my point, here's the evidence. This chart uses the Google Ngram Viewer to show the changing relative frequency of three terms that no one would ever use except in connection with seriously discussing Marxian economics: "monopoly capitalism," the "rate of surplus value," and the "organic composition of capital." The what? Yes, it's in my pamphlet.

And here is a link to the same chart in its native location, where you can play with it as you like.

As you can see, everything was going up until my pamphlet came out, and afterwards everything went downhill and never recovered.

January 16, 2014

Soviet Censorship: A Success Story

Writing about web page http://www.voxeu.org/article/costing-secrecy

Yesterday VOX published a short column that I wrote about Costing Secrecy. The teaser is as follows:

Democracy often seems bureaucratic with high ‘transaction costs’, while autocracies seem to get things done at lower cost. This column discusses historical research that refutes this. It finds empirical support from Soviet archives for a political security/usability tradeoff. Regimes that are secure from public scrutiny tend to be more costly to operate.

A starting point of my column was that communist rule in the Soviet Union gave rise to one of the most secretive systems of government that has ever been devised. I'm always looking out for ways to illustrate this, and I found a new way recently with the help of Google's Ngram Viewer(thanks to Jamie Harrison). The Ngram Viewer searches the Google Books corpus for words and word combinations and shows their changing frequency over time. The chart below shows the result of searching in the Russian corpus for the word "Главлит" (Glavlit).

Glavlit, the Soviet Union's Chief Administration for Affairs of Literature and Art, was created in 1922 to centralize the censorshop of the media. The background is that the Bolsheviks introduced censorship in November 1917 as one of the first acts of the Revolution (the "Decree on the Press"). During the Civil War that followed, they operated censorship through many agencies at many levels. Glavlit pulled it all together into a single, unified agency. The official title of Glavlit changed a few times over the next 70 years. Still, no one ever called it anything but "Glavlit," even in official government and party documents.

My current research is on secrecy. Censorship and secrecy are not the same. But they are closely connected. Enforcing government secrecy was one of the most important functions of censorship. In addition, Glavlit was a government agency, and its working arrangements were entirely secret, so the censorship had to censor the facts of its own operations.

How effective was Soviet censorship? The frequency with which the chief agency of censorship was mentioned in published works offers a simple measure in one dimension. Here it is:

Notes: My guess is that the Google Books Russian corpus must include books published in the Russian language abroad, out of reach of the Soviet censor, as well as within the Soviet Union. For transparency the chart is completely unsmoothed. In the years of the Civil War (1918 to 1920) and World War II (1941 to 1945) fewer books were published, making observations in those years more susceptible to the law of small numbers. You can view and play with the chart here in its home setting.

There is a simple message. The Soviet censorship agency was openly acknowledged and discussed at the time of its establishment and for a few years afterwards. From the mid-1920s it faded rapidly from sight. By 1931, when Stalin was fully in charge, its disappearance was almost total. For more than half a century Glavlit successfully covered its own tracks. Fifty-six years later, in 1987, Gorbachev launched his policy of "glasnost" (openness). Only then did Glavlit gradually come back into uncensored view. Glavlit was finally abolished in 1991.

In short: Soviet censorship worked.

December 24, 2013

Why Exactly Did She Give Me That?

Writing about web page http://ideas.repec.org/s/eee/givchp.html

It's sometimes suggested that festivals of giving and receiving challenge the theoretical foundations of mainstream economics. Not so. Christmas is a challenge, but it isn't abstract or theoretical; it's empirical and deeply personal.

How would Christmas be a theoretical challenge to economics? Most economists build their models on rational actors that pursue self-interest. I give you a gift. If my giving benefits you at my own expense, does giving undermine the axioms of the model? Not really. There are many ways to interpret giving in terms of rational choice. Here's a few.

- Love. I love you, so my utility internalizes yours. If my gift makes you happy, I'm happy too.

- Commitment. I signal my commitment to you by giving you an expensive gift. If you accept my commitment, we can do things together (like rearing a family) that we couldn't do separately.

- Competition. I compete for your affection by displaying my surplus resources. By making you a gift more expensive than any my rivals can afford, I can win the contest.

- Signalling. By selecting particular gifts (or store vouchers), rather than money, we signal particular types of affective relationships. Some gifts are considered romantic, and other utilitarian. When exchanges match, your position in my world is confirmed; when they are discrepant (you give me perfume, I give you a scrubbing brush) it is undermined. Either way, I learn something useful.

- To create an obligation (as Sheldon says in The Big Bang Theory, "You haven't given me a gift, you've given me an obligation"). I make you a gift, in return for which I will call in a favour at a time of my choosing.

These are a few possible explanations of giving and receving in general. One might also want to explain festivals of giving and receiving when everyone does it together:

- Herding. I gain utility from doing what everyone else does. If everyone else is giving and receiving, I'm happy to feel part of it by doing the same. (Not everyone is like this; a minority will gain utility from standing aside.)

- Coordination. It's more fun if we all do it at the same time; also, devoting a few days each year to systematic giving may reduce the chances of anyone being left out of our circles of commitment and obligation by mistake.

In other words, relatively simple extensions of the basic economic model based on rational individual choice can easily support explanations of giving, including festivals of giving and receiving. So the challenge of Christmas is not theoretical; it's not hard to explain the general phenomenon. The challenge is to explain giving in particular: For any specific gift, which is it, of these (or many other) possible explanations that applies?

Christmas is a challenge for everyone, not just for economists. Tomorrow, as you sit amidst the wrapping paper, ask yourself: Now, why exactly did she give me that?

Merry Christmas!

November 15, 2013

Which Dead Economist Must I Follow?

Writing about web page http://politicsatwarwick.net/2013/11/13/economics-and-the-crisis-which-dead-economist-must-i-follow/

I contributed recently to the Politics at Warwick blog, which I thank for its hospitality. My post elicited a comment to which I'd like to respond; my response is longer than my original post so I decided to include it here. First I'll put up my original post, dated 13 November 2013. Then I'll quote the comment and respond to it.

How should the economics curriculum respond to the global financial crisis and ensuing recession? Community activists and students have become vocal in this discussion, as recently described by journalist Aditya Chakrabortty and Matthew Watson.

Events have prompted questions about economists’ understanding of financial markets; the same events have generated a deluge of new data. How should economists respond? Economic research has already responded; hundreds of new articles have analysed global imbalances, market efficiency, corporate behaviour, regulation and deregulation, policy rules, the politics and economics of past crises, and the relative fragility of economic and political institutions in history.

The core curriculum has been slower to change. Here are two reasons. The first is that we no longer teach from handwritten notes and a chalkboard; students and teachers demand comprehensive textbooks with instructor manuals, PowerPoint slides, and websites. These take years to develop (and revise). Although slow, change is already visible. Because change is slow, there is more to be done. Change will probably accelerate through initiatives like the CORE (Curriculum Open-access Resources in Economics) project.

A better reason for inertia in the curriculum is our foreknowledge that the full meaning of recent events will take decades to establish – although many people believe that they are already obvious. To illustrate, today we continue to make new findings about the last Great Depression, which began in 1929, although many who lived through the 1930s were so certain of the answers that they were willing to kill and die on that basis.

How should the core curriculum change? A common complaint is that economics is dominated by a single school of “neoliberalism” or “market fundamentalism.” There are calls for more diversity in economics; some students want more access, specifically, to Keynes and Marx.

It is simply untrue that mainstream textbooks reflect principles of market fundamentalism. I can’t think of a principles text that doesn’t follow the initial explanation of market equilibrium with an immediate, detailed discussion of the varied sources of market failure and the regulatory interventions that might follow.

While one may learn from both Keynes and Marx, what is to be gained from taking them outside their historical settings? A Keynesian model focuses on flows (of income and employment) while neglecting stocks (of capital and debt). Yet capital and debt are very important! Keynesian principles are linked to a model of household behaviour (the “marginal propensity to consume”) that half a century of applied research has comprehensively invalidated. A Marxian model simplifies the continuum of capital ownership into a two-class society; additionally it throws out efficiency and substitution, so distribution is all that remains. In the context of today’s mainstream, each of these is now a stagnant, oxygen-starved backwater.

The importance of competing traditions is much overrated. Those that wish to organize the curriculum around them seem to believe that the major decision each economist must make is “Which dead economist must I follow?” and after that her research findings and policy recommendations will follow. This may be a natural reaction to the fact that mainstream economists are often unenthusiastic about policies that gather widespread popular support, for example rigid immigration controls, employment protection, and double taxation of corporate income. It might be easier for the supporters to say “Oh, those economists are all neoliberals who are ignorant of Keynes and Marx” than work patiently back through the evidence that fails to confirm their biases.

“Economics ought to be a magpie discipline,” writes Chakrabortty. But Economics is a magpie discipline. Most non-specialists – and most journalists – think public and private finance are all we do. They are amazed when I describe the sheer diversity of research that is done just in my department (here and here). We suck up topics and data from any time and place; we don’t care what discipline claims to own them. Then they backtrack and say, “Of course, I didn’t mean to criticize you (or Warwick), I meant Friedman (or Chicago).” The fact is there are no clear intellectual boundaries among schools of thought; we should all mingle in the same fluid mainstream, which is broader, deeper, and faster than you think.

Concluding, Chakrabortty reports a lament for the good old days. Tony Lawson recalls the Cambridge economics faculty in the time of Nicky Kaldor and Joan Robinson: “There were big debates and students would study politics, the history of economic thought.” I remember; I was there too, as a student. The big debates were an exercise in identity politics, not economics. Hostile clashes between intolerant armed camps ended in a war of attrition that benefited no one, least of all students. There is a warning here: be careful what you wish for.

On the day that my post appeared, the anonymous blogger Unlearning Economics posted a comment which you can read in full here after scrolling to the bottom. Here's my response, with excerpts from the comment inset.

Unlearning Economics quotes me and comments:

“A Keynesian model focuses on flows (of income and employment) while neglecting stocks (of capital and debt).” First, Keynes didn’t ignore capital or debt at all; that is simply false ... Keynes carried over some silly marginalist concepts like the efficiency of capital (clearly he mentioned capital once or twice).

My response: It is useful to distinguish between “things Keynes wrote about at various times” and “things that are core principles of the Keynesian model.” Of course we could argue about the division, but it seems to me capital and debt belong to the former, not the latter. The point is exemplified by Keynes’s model of consumer behaviour (more below), in which capital and debt play no role, although they were fundamental to other models available at the time. As for the marginal efficiency of capital, Keynes introduced this to rationalize his discussion of investment (a flow), not to understand the behaviour of the capital stock.

Again, Unlearning Economics quotes me and comments:

“Keynesian principles are linked to a model of household behaviour (the “marginal propensity to consume”) that half a century of applied research has comprehensively invalidated.” Which research would this be? “People don’t consume all of their income” is hardly a false statement.

My response: Yes, it's true that “people don’t consume all their income,” but that isn’t the issue. The issue is whether the main thing in consumption is a stable proportion between household consumption and current income at the margin, as Keynes believed. I should add that he not only advanced this idea in theory but also applied it in practice, for example in his writing about how to pay for World War II. Franco Modigliani, Milton Friedman, and others investigated this idea after the war and failed to find it in the data. They did identify a stable relationship between consumption and wealth, or lifetime (or "permanent") income, to which changes in current income make a small or negligible contribution. Because permanent income is uncertain, the future (including expectations of inflation and the real interest rate) are fundamental. Modern new-Keynesian models drop the marginal propensity to consume (and the multiplier) and focus exclusively on intertemporal substitution intended to smooth consumption over time. Which takes me on to our next point.

Unlearning Economics adds:

Second modern post-Keynesian is *all about* stock-flow consistent models ... people like Godley, Keen etc have updated [Keynes’s] work.

My response: Yes, certainly. Here another distinction arises, between Keynes and the post-Keynesians (or Marx and the post-Marxists). Naturally, there is development in the Marxian and Keynesian traditions. I could not dispute that, when a great economist produces an insight that turns out partial or incomplete or defective in some respect, it may be fixable. There is evolution. Evolution has produced neo-Keynesians and post-Keynesians (and Marxists). Evolution is better than stagnation. At some point it generates new species. Every year I help teach a “new-Keynesian” model of the macroeconomy to Warwick undergraduates, and every year I (and I hope they) learn something new. Yet the label “new-Keynesian,” like George Box’s economic models (more below), although useful, is also wrong. Would Keynes recognize it as his? It’s debatable. Does it matter? Only if you want to claim ownership over Keynes’s legacy.

Unlearning Economics quotes me and comments:

“A Marxian model simplifies the continuum of capital ownership into a two-class society; additionally it throws out efficiency and substitution, so distribution is all that remains.” Marx spent a lot of time talking about the difference between financial capital and industrial capital; Lenin updated his work in the context of ‘globalisation’ (imperialism). I also have no idea how you got that Marx “throws out efficiency and substitution”: he continually praised the efficiency of capitalism, and substituting capital for labour is the main driving force behind the tendency of the rate of profit to fall.

My response: I considered proposing that “efficiency of capitalism” belongs to “things Marx wrote about at various times” rather than “things that are core principles of the Marxian model.” On reflection, however, I am not convinced that Marx had a concept of efficiency at all, not in the sense that economists use it today (when you can’t reallocate resources without using more of some input or consuming less of some output). Marx did write a lot about the productiveness of capitalism, but I do not think he was thinking about total factor productivity.

Similarly, I do not think Marx had a concept of substitution in the sense of a choice between alternatives that varies with their relative price. Yes, it’s possible to rewrite Marx’s idea of the organic composition of capital (the constant/variable capital ratio) as capital/labour substitution, but that is not at all how Marx described it. His idea (Capital III, chapter 13) was that over time the ratio of constant and variable capital in value terms will tend to rise, but that seems to be driven by the accumulation of capital, not by relative factor prices. What is described is a process that piles capital up faster than labour; there is no process that allows substitution between them along a frontier. With labour the only source of surplus value, the rate of profit on capital must tend to fall.

Since Unlearning Economics charges me at the outset with “complete ignorance of Keynes and Marx,” I thought I had better come up with a test of Marx’s understanding of substitution. When I teach the subject of economic warfare I put a lot of emphasis on substitution. People who are not mainstream economists (military commanders, for example) often make biased predictions about the effectiveness of blockades and sanctions, and this is because they lack a concept of substitution. They expect a blockade to curtail production and so to cause the rapid downfall of the blockaded economy. In history, the curtailment of trade has generally brought about relative price changes that stimulate substitution and in turn this will make the blockade less effective than expected. So I looked to see how Marx wrote about blockades.

In 1861 the American Civil War led to a blockade of the Southern ports. The Confederacy responded with a cotton embargo; they thought this would trigger such a crisis in Britain’s textile industry that London would have no choice but to intervene on the Confederacy’s behalf. In the autumn of 1861 Marx wrote (in several places including here, for example) predicting that the stratagem would succeed: “England is to be driven to break through the blockade by force, to declare war on the Union, and thus to throw her sword on the scales in favour of the slave-owning states.”

It did not happen. In Britain the price of raw cotton shot up (which Marx could see), and this stimulated a search for alternative supplies, soon found in Egypt and India (which Marx entirely discounted). He had made the characteristic error of someone who does not get substitution.

Back to George Box, who wrote that “all models are wrong, but some are useful.” The models you can find in Keynes and Marx are no different; they are all wrong in the Boxian sense. Are they useful? Sometimes, yes. Marx’s idea of surplus extraction is useful for understanding societies with closed elites and extractive economies, although not modern capitalism. Keynes’s idea of animal spirits gives insight into modern capitalism as a nice corrective to the idea of rational expectations. But, why should I, or you, or anyone confine themselves to the limits of any “wrong” model by declaring that I am a Keynesian or a Marxist? When scholars do that, it surely tells us more about the politics of identity than about their scholarship.

In fact, I fear that the tone of this discussion may exemplify my final point: when social science is polarized into schools of thought, s/he who is not with me is against me and personal rancour is the likely product.

October 14, 2013

Who's a Marxist Now?

Writing about web page http://www.conservativepartyconference.org.uk/Speeches/2013_George_Osborne.aspx

At the Tory conference George Osborne, Chancellor of the Exchequer, made an interesting point about the views of Ed Milliband, Leader of the Opposition:

For him the global free market equates to a race to the bottom with the gains being shared among a smaller and smaller group of people. That is essentially the argument Karl Marx made in Das Kapital. It is what socialists have always believed.

Osborne’s point made me think about the influence of Marx on modern intellectual life. To many this is something of a puzzle. Isn’t Marxism discredited as a political philosophy? Haven’t the economic policies of Marxist regimes generally failed to provide for “an association, in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all” – the words by which Marx once distilled the goal of communism? How many of those that identify with the ideals of socialism today have actually read and followed even one page of the fifty volumes of the Marx-Engels Collected Works?

My answers: Yes, Yes, and Not many. Yet Marxism shows no sign of dying out; it lives on in a variety of political movements and branches of academic and cultural life.

Why’s that? The question is puzzling only if we think of Marx as the the reason why Marxist ideas exist. Of course Marx was the originator of Marxism, but I am quite sure that if Marx had never been born to invent Marxism, some other scribbler would have taken his place. The basic ideas that underlie Marxism pre-existed Marx, and would have existed without his writings, and are continually reborn and propagated among people who know nothing of Marx for a straightforward reason: because such ideas correspond with how most people experience everyday life. Marx’s importance, therefore, was not as the discoverer of these ideas but as the writer that gave them a scholarly form.

What are the experiences to which Marxist economics correspond? Behind the complicated terminology of capital and value and Marx’s elaborate philosophical and historical argumentation of them are four simple ideas:

- The market is a jungle, a chaotic struggle of each against all, in which the strongest, most ruthless predator wins. Lurking behind every transaction is the chance that someone will rip you off.

- Of all the possible functions of market prices – accounting, economising, distributive – the only one that matters is distribution. A rise in the price of food or fuel cuts the real income of workers and redistributes it in favour of the producers that employ them.

- Work is hard and stressful, and the main source of pressure is the employers' drive to make you work harder and longer, in order to save them money or increase their profits.

- You can’t do anything about this on your own. Idealistic advocacy has no traction without numbers. Everyone should get together and intervene forcibly to bring about radical improvement.

What kind of economics do these four ideas make? They make the economics of everyday lived experience for most of the world’s seven billion people. I’m not talking just about the poor and ignorant. It’s nothing to do with education or position in society. My guess would be that most people in my immediate circle of family and friends that are not trained economists hold, most likely, two or three of the four ideas; I expect that all might hold at least one.

Suppose you decided to give your life to elaborating these four ideas and you spent years working them up into a philosophy of economics: What kind of book would you write? I think you’d end up writing something pretty much like Das Kapital. In other words, Marxism is a philosophization of the economics of lived experience, but it's the economics of lived experience that should really demand our attention.

What kind of economics would lived experience support? It would make, in the words of Frederic Bastiat, the economics of “that which is seen.” It would take into account only the most immediate effects of things. It would leave out the other effects, those that “unfold in succession – they are not seen: it is well for us,” Bastiat went on, “if they are foreseen. Between a good and a bad economist this constitutes the whole difference – the one takes account of the visible effect; the other takes account both of the effects which are seen, and also of those which it is necessary to foresee.”

What’s wrong with the economics of “that which is seen”? By analogy, think of the physics of “that which is seen”: the earth is flat and parallel lines never meet. Or the chemistry of “that which is seen”: burning is the release of phlogiston. I’m not saying that economics is a science like physics or chemistry in all respects. What I’m saying is that Euclidean geometry, the idea of a flat earth, and the theory of phlogiston are perfectly serviceable for making sense of a number of things everyone can see from day to day. It’s true, though, that these ideas miss out badly on other things and this prevents them from being useful in many contexts. For the purposes that are missing, we need more; we need the physics and chemistry of “that which is not seen,” including molecular science, gravity, and relativity.

What is added by the economics of “that which is not seen”?

- The market creates many opportunities for sellers to abuse buyers, yet the market is not chaos: it enables specialization and competition. The same market economy that often feels like a jungle is the mechanism that has sustained the West’s unprecedented prosperity and is also the hope for sustained progress of the Rest. But this is not seen because it has taken hundreds of years to materialize; life’s too short for it to be seen. (My colleague Omer Moav makes a similar point in a penetrating review, which he showed me recently, of Ariel Rubinstein's Economic Tales.)

- If something that you consume is in short supply so that the price goes up, you lose in the short term, and this is seen. Beyond this, however, is an unseen process by which all gain. There is adaptation. Responding to the increased cost, we economize on uses, we search for substitutes, and we find or create new sources of supply. The adaptation is not seen because it would require the simultaneous observation of a million small responses.

- Work is stressful, and a predatory employer can increase the stress for the sake of profit. But that is incomplete. In the Marxian perspective there is only one kind of surplus, called profit, one source of surplus, called labour, and one class of recipients, the capitalist class. In the competitive market economy every transaction gives rise to a surplus on both sides. Day by day, billions of small surpluses accrue to both sides, buyers and sellers, that are party to every transaction. In other words, there are surpluses everywhere and they accrue to everyone; they are not the monopoly of one class. But this, too, is not seen.

- Everyone getting together to force change does not always make anything better, and this might be the case quite often. This is not seen for two reasons. First, in every case to establish the results of intervention requires the careful construction of a counterfactual (in other words, what would have happened without the intervention) which, to most people, seems intolerably speculative. Second, when intervention has demonstrably not brought about the benefit sought, there is a natural human tendency to shift the responsibility from our own action to the counteraction of those that disagree with us, whom we make into scapegoats.

Whatever things are not seen, it’s hard to know they are there. Understandably, therefore, most people stick to the economics of what they can see for themselves. Most of those don’t think of themselves as Marxists or even socialists. Still, it ensures a reservoir of instinctive sympathy in our society for ideas that are aligned with Marx's and helps to explain his lasting influence. This reservoir is continually refilled from everyday experience. That's why Marxist ideas live on and will often be well received by well educated, well intentioned people.

Full disclosure: In years gone by I considered myself a Marxist and I read a lot of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, Mao and others. At various times I joined a Capital reading group, and taught the economics of Marx (alongside Smith, Ricardo, List, and Schumpeter), and I even wrote a pamphlet called The Economics of Capitalism; I still have a copy; one day I’ll scan it and put it on line. Somewhere between that time and this, however, I changed my mind for reasons that I wrote down here.

September 16, 2013

Rebalancing China — rebalancing the world

Writing about web page http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/03377ccc-16e0-11e3-9ec2-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2ezCPilYN

Last week I went to Downing Street for an informal discussion about Britain and China ... No, not with the prime minister, but between some academic China watchers and a couple of prime ministerial aides. Here I can only say what I said myself, but I thought afterwards whether I could package it for general interest. Here's the basic idea.

The Chinese government is currently trying to rebalance the economy. This will create both opportunities and risks for a country like Britain that exports worldwide and also has some world-class corporations that are willing to invest worldwide. It's important to be aware of what the opportunities are, and also the risks.

What does rebalancing mean? It means, primarily, trying to build China's mass market for consumer goods and services. The composition of China's spending must shift somewhat away from government and infrastructure towards consumption and the mass market. This does not mean that the government will become unimportant or that China will stop building new towns, universities, and transport systems. All of these are already huge and since the economy is still growing relatively rapidly they will remain important and also continue to grow. But net exports and capital formation together account for well over half of China's GDP, making one of the highest saving rates ever recorded for a modern economy. In other words, there is a lot of room for consumer spending to grow more rapidly at the margin, if only the pressure of government spending on infrastructure and military projects will allow it.

When China's prime minister Li Keqiang says "we will expand consumer demand" (in the FT, 8 September 2013), that doesn't make it happen, of course. The UK coalition government has talked about rebalancing our economy away from financial services to manufacturing for some time. That hasn't made it happen. Even in a totalitarian police state, rebalancing the economy can be quite difficult. Stalin's first attempt at rebalancing came in 1932, the last year of his first five-year plan, when too much capital formation and rearmament were killing off millions of people from famine. Rebalancing was urgent -- literally, a matter of life and death. The second five year plan was being written. It was supposed to rebalance the economy back towards consumption. Consumption did recover, but it was not a great deal more than a dead cat's bounce. After a year or two investment and rearmament took off again. The whole economic system had been designed around creating a surplus for accumulation and military spending. Given that, it was pretty hard for it to do anything else.

China's economic mechanism has also been designed around accumulation and military spending. An important problem with rebalancing China towards consumption is that success might weaken the drivers of the mechanism underlying China's huge success of the last 30 years. This mechanism is the rivalry of China's provincial leaders, each of whom compete with each other to win favour with Beijing and promotion to Beijing by pushing the growth of production in their own province. That growth depends a lot on infrastructural investment. If the provincial leaders can't push infrastructure as strongly before, then Beijing will have made it harder for them to compete. If they don't compete as strongly, the economy may falter, undermining the core purpose of rebalancing.

Still, China's ruling party has come to accept that a growing mass market can stabilize society and relax social tensions, making China stronger internationally. So let's suppose they can make it happen. There are opportunities here for British businesses to meet rising consumer demand, whether by exporting or by investing in China and producing within China's borders. As people get richer they want to be healthier, and better informed, and to enjoy faster communication. There is sure to be rising demand for things like telecoms and pharmaceuticals that Britain is good at making and doing.

One problem with exporting to China and investing in China is that China's market is very wide -- too wide, in fact. It is spatially highly dispersed, because too many Chinese live in small towns and rural settlements. It is also not very well integrated, with significant barriers to internal trade across provincial boundaries -- a product of the inter-provincial rivalry that has helped China's past growth. In other words, if you sell to the Chinese, you might expect to go to a market of 1.3 billiion people, but what you actually reach is one of 30 or so provincial markets. Of course, this isn't so bad because a typical province in China is the size of a European country in population, which is pretty big. It's also true that China's market integration is most likely improving over time. Still, it doesn't yet add up to the idea of selling a lightbulb to every Chinese family.

Another problem is that China's market has many, many opportunities for vested interests to conspire with government officials against competitive threats (and therefore against the consumer). Corruption remains a huge problem. China's government is currently waging an anti-corruption campaign. Anti-corruption is fine, but the campaigning aspect is problematic. The best way to reduce corruption is to reduce product market regulation and have open, competitive markets and the rule of law. China's communist party continues to prefer party rule to the rule of law. The result is that, when you see a person (like Bo Xilai) or an organization (like GlaxoSmithKline) targeted for corruption, you can't really be sure whether they are guilty as an impartial court would see the evidence, or whether the political authorities decided to make them guilty of something and then make the evidence up.

That's a particular risk for foreign investors in China. Of course, foreign investors face risks everywhere. Anyone who has followed the recent history of BP in the United States will be aware that a foreign corporation can become a target even in a liberal democracy with an independent judicial system. The point may be that at least BP had first to do something wrong before it became a target. In a corrupt police state like China's, in contrast, you can get into trouble even if you did nothing wrong. Or perhaps, more accurately, there are contexts in which everyone bends the rules, or the rules may be so complex and pervasive that you can't operate at all without breaking them somehow. Then, the foreign investor either sticks to the rules, which leaves you unable to compete, or you compete and break the rules like everyone else, but that means you are making yourself ever vulnerable to those in power. Indeed that might be one purpose of a rule book that no one can adhere to conscientiously.

Finally, helping China to build its mass market is an opportunity for British business, but it is important to recognize that for China's leaders building the mass market is not an end in itself but an exercise in national power-building. Prime minister Li acknowledged this when he linked China's mass market with sustainable growth and both of the latter with "national strength." In other words, if we help develop China's consumer market, we should do so with open eyes: we are also colluding with a project that is designed to reduce our own country's relative power and influence in the world to China's benefit.

Is that a reason to stand aside? In my view, not at all. In the long run, free trade and investment have civilizing power. (In case anyone thinks that's snobbish, I mean it literally: free exchange develops civil-society institutions in ways that governments cannot.) Countries that make themselves economically interdependent are are then somewhat less likely to come into conflict. That's not a deterministic statement, by the way. The power of trade is double edged, because trade can be exploited to build national power. The civilizing influence of trade takes lots of time. It works through probabilities, not certainties. It's an average thing, with plenty of variation and historical counter-examples.

So we should trade with China and invest in China with our eyes open. We should remain aware that China's rulers are heirs to the communist tradition. In this tradition the world is an arena for a zero-sum power struggle in which, in the long run, one country's gain is likely to be another's loss. These leaders want China to develop its mass market not for the sake of consumer welfare but because a more sustainable Chinese economy and a more stable society will better support their national and international strategic goals.

The benefits that we should seek from economic interaction with China are those that will flow to the citizens of both countries, and to consumers as well as producers. For example, the benefits of trade and investment will come back to the British economy not only through our exports to China's growing market but also by access to imports from China that lower prices and raise living standards in Britain.

August 29, 2013

History suggests intervention in Syria will be bad for business

Writing about web page http://theconversation.com/history-suggests-intervention-in-syria-will-be-bad-for-business-17611

Since last week’s gas attack on a Damascus suburb, the political class has been gripped by the idea that “something must be done.” Meanwhile Wall Street, already declining through early August, fell further as this week began. At the same time oil prices have ticked up sharply, not because Syria is a significant oil producer, but in response to fears for Middle Eastern supplies generally.

A military attack on Syria would clearly affect stock values. War diverts trade: some businesses lose while others gain. Is war good for business in the aggregate? Not likely. When an economy is depressed, and the fighting is at a comfortable distance, additional military spending might give a short-run stimulus to business for everyone. In the long run, however, war is a wealth-destroying activity. Because stock values reflect long-run profit expectations, the chances of a positive aggregate effect from hostilities are vanishingly improbable.

It is a somewhat different question whether the launching of an attack will move stock values on the day. Cruise missiles rarely come from a blue sky. Those for whom war has clear implications will usually have looked into the future and hedged their bets.

On the day the fighting starts, it is true, war changes from a probability to a certainty. But if the probability was already seen as close to 100%, the impact on asset values will inevitably be small. Only a true surprise would move them by much.

Economic historians first became interested in this topic in connection with World War I, the outbreak of which was a surprise to many. Niall Ferguson (in the Economic History Review 59:1 (2006)) and others (Lawrence, Dean, and Robert in the Economic History Review 45:3 (1992) have documented that as the war began European bond prices fell and unemployment rose in London, Paris, and Berlin. The panic on Wall Street was so great that the New York Stock Exchange was closed for the rest of the year.

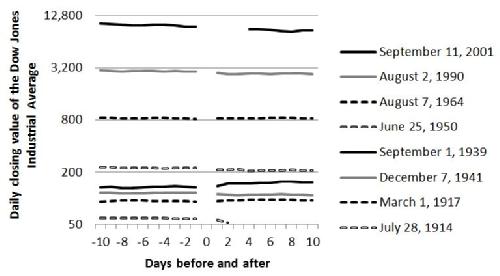

To update the record across the last 100 years, the chart below shows closing values of the Dow Jones Industrial Average in New York for the ten working days before and after eight war onsets (the value on the day itself is omitted).

Source: Mark Harrison, "Capitalism at War," forthcoming in The Cambridge History of Capitalism, edited by Larry Neal and Jeff Williamson for Cambridge University Press. [Thanks to Christopher Renner for drawing my attention to a misprint and a small error in the first version of this chart.]

The days shown are:

- September 11, 2001: Al-Qaeda attacks American cities

- August 2, 1990: Iraq invades Kuwait

- August 7, 1964: Gulf of Tonkin Resolution

- June 25, 1950: North Korea invades South Korea

- December 7, 1941: Japan attacks Pearl Harbor

- September 1, 1939: Germany invades Poland

- March 1, 1917: The Zimmermann telegram published

- July 28, 1914: Russia mobilises against Germany

Only two of these events saw stock prices climb, and then only slightly. In five cases they fell, and in two the stock market was closed (for more than four months after the outbreak of World War I in Europe, and for four days after 9/11).

Notably, although stock prices rose a little after Hitler’s attack on Poland in 1939, they fell thereafter. When Pearl Harbor arrived, they remained below the level recorded two years earlier. The median change in stock prices over the eight crises was a 5.3% decline.

Contrary to commonly held opinion, war has also been bad news generally for the very rich. Tony Atkinson, Thomas Piketty, and Emmanuel Saez have collected historical data on top incomes in many countries across the twentieth century. These show sharp wartime declines in the personal income shares of the very rich in every belligerent country for which wartime data are available.

This does not rule out the idea that a few corporations gain business, and a few people become richer as a result of conflict. It just tells us that the average effect goes the other way. Besides, war is always first and foremost a political act. If Western bombs fall on Damascus in the next few days, it will be because someone decided it made good politics, not good business.

Mark Harrison does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.![]()

This article was originally published at The Conversation. Read the original article.

July 16, 2013

Protectionism: A Fairy Tale of the State and War

Writing about web page http://www.pieria.co.uk/articles/in_defence_of_protectionism

On Pieria, John Aziz writes in defence of protectionism, that is, the use of taxes and subsidies to shield a country's economy from foreign competition. He begins from the Ricardian story of the benefits of two countries sharing the benefits of free trade based on comparative advantage.

England was good at producing wool, Portugal wine, so they trade and both are better off. There is the fairy tale about how because market transactions are always voluntary and always beneficial that trade, being simply a market transaction across borders, is always win-win.

But this, he says, is a "fairy tale." In real life, he argues, comparative advantage has little to do with resource endowments and is generally artificial. Comparative advantage may be part of the historical pattern, he concedes. But it misses something essential. What's missing? He goes on.

Let's imagine a model with two different goods, say, guns and butter. England specialises in producing guns and munitions, and Portugal in butter and agricultural produce. For years, they trade and enjoy the benefit of maximising output through specialisation. Then, England starts a trade dispute with Portugal. They cease trading. England loses access to butter and various agricultural products from Portugal's large population of butter-producing cows, having to replace Portuguese butter with lower-quality and higher-priced Welsh butter. Portugal, however, loses access to guns and munitions. Although this is immediately recognised as a risk to national security, and Portugal quickly tries to start up its own domestic firearms industry, the trade dispute escalates into full-blown war and with their geostrategic advantage in guns, England swiftly triumphs and occupies Portugal.

The implication is clear. Portugal should have insured itself against the contingency of conflict with England by limiting trade through protectionism. By means of an interventionist industrial policy, Portugal would have developed its own guns and could then have resisted England.

Several things are noteworthy about this argument.

First, it too is a fairy tale. As John Aziz rightly points out, there's nothing intrinsically wrong with that. All our models are fairy tales. The point is that some are useful and others not. How can we tell? We test them against stuff that has actually happened. If they survive the confrontation, then we can use them to suggest practical implications for the future. So, the fact that it's a fairy tale is of interest, but it's not a problem. Let's move on.

Next noteworthy point: Let's test this model against something that actually happened. Not literally, because England has not been to war with Portugal since long before gunpowder came along. Replace Portugal by Germany, however, and the fairy tale suddenly acquires an ominous ring of truth. Doesn't it have an uncanny fit with what happened in 1914?

No, not exactly. In 1914 Germany and Britain went to war. While Britain was the pioneer of free trade, Germany had practised protectionism since 1879. German tariffs limited trade and promoted self-sufficiency in both industrial and agricultural goods. In Britain, by contrast, free trade accelerated the decline of agriculture and maximized the exposure of the British economy to imports. In 1913 at least 60 percent of the calories used at home for human consumption were imported. Many observers thought that left Britain ridiculously vulnerable to wartime blockade. German naval strategists agreed. It's true that in World War I food became a weapon of war just as much as guns.

Yet in the outcome it was Germany, the protectionist power, that struggled to manage the wartime disruption of trade and saw civilians die of hunger, while the British got by without serious shortages.

What explains this turnaround? As Mançur Olson (1963) argued (and before him Friedrich Aeroboe), the German economy entered the war in 1914 already weakened by protectionism. Food tariffs had encouraged peasant farmers to stay on their farms. This kept a large subsistence agriculture in being and reduced productivity and incomes. Because German farmers were already well into diminishing returns it was then hard to increase output at need, when war broke out.

As for industry, because imports of food into Germany were restricted in peacetime and labour held back in agriculture, German urban employers faced higher wage costs. To compensate for higher wage costs, industrial firms economized on labour and pushed up productivity. But across the economy as a whole, efficiency and average incomes were reduced.

A history of protectionism gave no national advantage in either World War. I've argued (in several places; see Harrison 2012 for example) that the main factors that gave systematic advantage were a country's size and wealth, and the main source of disadvantage was a peasant-based agriculture.

In that case, what's protectionism all about? In understanding protectionism, redistribution is much more important than development. Whether tariffs and subsidies raise or lower long-run growth, in the short run they redistribute income away from consumers and exporters to import-competing firms, often by very large amounts. This should draw attention to their political significance. As Dani Rodrik (1995, p. 1470) once wrote:

Saying that trade policy exists because it serves to transfer income to favored groups is a bit like saying Sir Edmund Hillary climbed Mount Everest because he wanted to get some mountain air.

In history, protectionism has given politicians a powerful instrument to bind those "favored groups" into their projects. To Bismarck, protectionism was political: it brought together the interests of "iron and rye" to share rents and support Germany's "peaceful rise." Similar motivations lie behind most real-life experiments in protectionism that I am familiar with. The only real exception is the Soviet experience of autarkic industrialization; that was different because Stalin was an absolute dictator who ruled by fear and had no need to pay off campaign funders.

Modern promoters of the developmental state (including Dani Rodrik) could reply that they advocate only those selective interventions that are designed to improve social welfare, not corrupt the political process. That's an argument I understand, but it requires a benevolent, far-sighted government with the power to intervene and the self-restraint to do so only for the common good, not for the good of its supporters. That's a bit of a problem. I don't see a political system anywhere, short of totalitarian dictatorship, in which you could advance those policies and see them implemented without vested interests jumping on your bandwagon and hijacking it for their own purposes, which will have nothing to do with social welfare.

(It's ironic, then, that John Aziz lists "graft and corruption" as a problem of trade liberalization, because opportunities for corruption are created only where the government has something to withhold.)

The historical link between protectionism and aggressive nation building is strong. Using data for 1950 to 1992 Erik Gartzke (2007) has shown that restricting a country's trade and capital flows is a good predictor of its propensity to engage in conflict. From data for 1865 and 1914, Patrick McDonald and Kevin Sweeney (2007) have shown that protectionism was a robust precursor of engagement in "revisionist" wars.

John Aziz concludes with a warning:

China's monopoly on rare earth metals which have very many military applications may have national security implications for other nations including Britain and the United States whose ability to manufacture modern military equipment might be impeded by a trade breakdown.

Shouldn't we worry? Yes, but that's because we need to understand China, not because we should be preparing for war. Indeed, one of Mancur Olson's key conclusions was that it's a mistake to think of particular raw materials, and even oil or food, as in some way "strategic" or "essential." Only the final uses of resources are essential. In practice, if some particular material suddenly becomes scarce, the price goes up and and opportunities present themselves to economize at the margin or find alternative sources or substitutes.

The price goes up, it's true. In other words, the alternatives may be costly. But the richer you are, the more easily you can meet the cost. That's why rich countries survive trade disruption and win wars. As for protectionism, to the extent that it diverts resources from their best uses, it makes the country poorer in advance and so less able to afford the measures that might become necessary in a national emergency.

Which brings me to the last noteworthy point about the arguments that John Aziz makes: They have nothing to do with personal well being. As he correctly comments:

The relative value of outcomes is simply a matter of one's criteria.

In truth, the two fairy tales that he tells differ in addressing completely different criteria. The free-trade fairy tale always was and is about the personal welfare of all members of society. Here, society is global: when trade is free, all gain, not just the residents of one country. The protectionist fairy tale, in contrast, is about nation-building and facilitating conflict in a world where elite coalitions build states, states compete for power, and a gain for one country is a loss to others.

The world is a complicated place. In the same spirit as John Aziz when he notes that the free trade story has some merit, I'm going to accept that the unregulated interaction between real world economies sometimes creates losers. There have evidently been historical circumstances when protectionist policies accidentally did no harm, or even did good by accidentally correcting some market failure.

But the design of protectionism has generally been far more driven by vested interests and power building than by concern for social welfare. Those who enter themselves in the reckoning against free trade often rely on an idealized understanding of the record.

References

- Gartzke, Erik. 2007. The Capitalist Peace. American Journal of Political Science 51:1, pp. 166-191.

- Harrison, Mark. 2012. Pourquoi les riches ont gagné: Mobilisation et développement économique dans les deux guerres mondiales. In Deux guerres totales 1914-1918 − 1939-1945: La mobilisation de la nation, pp. 135-179. Edited by Dominique Barjot. Paris: Economica, 2012 (here's a preprint in English).

- McDonald, Patrick J., and Kevin Sweeney. 2007. The Achilles’ Heel of Liberal IR Theory? Globalization and Conflict in the Pre-World War I Era. World Politics 59:3, pp. 370-403.

- Olson, Mançur. 1963. The Economics of the Wartime Shortage: A History of British Food Supplies in the Napoleonic War and in World Wars I and II. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Rodrik, Dani. 1995. Political Economy of Trade Policy. In Handbook of International Economics, vol. 3, pp. 1457-1494. Edited by Gene Grossman and Kenneth Rogoff. Elsevier.

Mark Harrison

Mark Harrison

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…