The Meaning of Christmas, 1914: When Peace Broke Out

Writing about web page http://www.wsj.com/articles/the-spirit-of-the-1914-christmas-truce-1419006906

At Christmas 1914 up to 100,000 troops on the Western front took part in unofficial truces. They left the opposing trenches and exchanged greetings, cigarettes, food, and drink. Most famously, some of them may have played football.

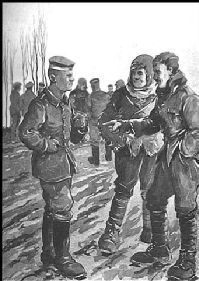

The moment was captured by Bruce Bairnsfather (1917); thanks to Major and Mrs Holt, Bairnsfather's biographers, for permission to reproduce this image.

The Christmas truce of 1915 is often considered to be something rather unique. In fact, as the sociologist Tony Ashworth (1980) showed, it was a special case of a wider pattern. The Christmas truce was special because there was open fraternization. The wider phenomenon was simply a tendency for the soldiers on both sides, left to themselves, to bring down the level of conflict and hostility. They did this spontaneously, without calculation, using coded signals that did not need to be translated into words or confirmed by shaking hands. The signals were the dawn volley, aimed far above the enemy's heads, or the tea-time shell that always fell wide of the mark. These were signals of a lack of hostility that the receiving soldiers could easily come to recognize, predict, and reciprocate.

In this way the soldiers on each side would learn to collude with the enemy to avoid direct clashes and minimize the danger on both sides.

Ashworth called this pattern of behaviour "live-and-let-live." Live-and-let-live was observed in all periods of the war; the Christmas truce of 1914 was unusual only in that the men's desire to avoid outright hostilities was expressed openly. But it did not need to be expressed openly to persist. Live-and-let-live could develop without any explicit communication.

The crucial condition for live-and-let-live to develop was that the men were left alone for long enough to learn its language. But military commanders learned not to leave their men alone. They learned to intervene in the game of live-and-let-live and to disrupt it by teaching their men another language, the language of hostility. In between the great offensives, the soldiers learned the language of hostility in night raids. Night raiding involved crossing to the enemy trenches under cover of darkness to surprise, kill, destroy, steal, and kidnap. Night raids were dangerous, caused losses to both sides, stimulated the desire for revenge, and engendered persistent mutual hostility.

For all the same reasons, night raids were universally detested. The British and French officers approached this problem differently. The result was a kind of field experiment in different types of motivation. The French officers asked for volunteers and used positive incentives and rewards to encourage participation. In contrast, the British officers used direct orders that required all troops to take part in rotation.

The result, according to Ashworth, was that in the French army night raiding was generally regarded as exceptional service, demanding special recognition. In the British army, on the other hand, night raiding was seen as one of the regular duties of front line service. Because of this, the British were able to carry out the policy of night raiding at a higher level than the French in 1915 and subsequent years. In the British sector there was more hostility and live-and-let-live was cut off at the root. Armed with superior motivation, the British troops then showed greater commitment in both minor and major offensives.

In contrast, Ashworth argued, French morale declined to the point where, in 1917, faced with orders to go once more into battle, half the regiments in the French army experienced mutinies. Ashworth supported his argument with a striking fact: On the German side of the French sector in 1917 there was no awareness that the troops in the opposing trenches were refusing orders to attack. This can only mean that the German soldiers had become completely habituated to the French passivity and so saw no change in the behaviour of the French soldiers.

Could the Christmas truce have ended the war before it had barely begun? Was it a lost chance to avert the premature deaths of tens of millions of people? It is a tempting thought, but we are bound to conclude that there are several reasons why this could not have been the outcome.

Live-and-let-live was surely facilitated by trench warfare, when large numbers of soldiers faced each other for long periods across static lines, and could learn to reciprocate each others' behaviour. But static warfare was temporary. The war began with movement, and by the time it ended the ability of the troops to move had been restored by new weapons and technologies.

If the war had ended on the Western front in December 1914, it would have left Germany in possession of a large slide of eastern France. The French leaders would surely have resumed the war at some point for this reason.

If the war was not quickly restarted in the West, Germany's leaders had another war to fight in the East, a war on Russia that in their strategic vision was more vital to Germany's interests than the war on France. The Germans would surely have exploited a truce in the West to pursued the war in the East with redoubled energy.

In fact the political leaders and military commanders were able quickly to overcome the natural tendency to live and let live and so return to the war. They were learning rapidly how to mobilize their nations around national identity, how to use their economies to deploy and arm millions of young men for combat, and how to organize those young men into fighting organizations that would attack and defend in together in large-scale operations, regardless of victory and defeat.

The Christmas truce of 1914 is testimony to the intense desire of most young men not to die and not to kill. It is also evidence of the growing aversion to extreme violence that writers such as Steven Pinker (2011) have identified over thousands of years of human history. It reproaches the rulers of 1914 that condemned Europe to thirty years of mass warfare. But it did not and could not overcome the political calculations that led to war at that time.

In 2014 the Kremlin's political calculations have led to war in Ukraine. Russian leaders seem to have no qualms when they threaten to widen the use of force in Europe by means of rapid rearmament, large-scale miltary exercises, and continuous probing of NATO air and sea defences, and by talking up the use of nuclear weapons.

From one end of Europe to the other today there is ample evidence of the innate desire of ordinary people to live and let live. But live-and-let-live does not offer a solution to the problem of authoritarian rulers that make their war plans in secret, free of moral and political restraints.

References

- Ashworth, Tony. 1980. Trench Warfare, 1914-1918: The Live and Let Live system. London: Macmillan.

- Bairnsfather, Bruce. 1917. Fragments from France. New York and London: The Knickerbocker Press.

- Pinker, Steven. 2011. The Better Angels of our Nature: The Decline of Violence in History and its Causes. London: Allen Lane.

Mark Harrison

Mark Harrison

Loading…

Loading…

Add a comment

You are not allowed to comment on this entry as it has restricted commenting permissions.