Pedagogy of the Artificial talk, Café Scientifique, April 28th

Follow-up to Learning as design[ed] at Café Scientifique, April 28th from Inspires Learning - Robert O'Toole

The Café Scientifique proved to be a great event. Congratulations to Jayne and her team! It was really well organised and provided a great "interdisciplinary" forum for new research. The two (by chance related) arts or social science papers contrasted interestingly with the science paper - although there were connections. This immediately raised questions about how we work and the purpose of communicating research - questions addressed directly in my paper.

During the writing of my presentation, the title slowly morphed into "Pedagogy of the Artificial", a reference to Herbert Simon's "Sciences of the Artificial" (Simon, 1969) and Richard Coyne's excellent paper "Wicked Problems Revisited" (Coyne, 2004) which brings Deleuze and Guattari to the party. Sadly, I had to edit things down to get within any hope of the ten minute limit. An interesting digression on the origins of design thinking in the baroque, via Deleuze's The Fold, was removed.

Thanks to everyone who asked questions and gave feedback (and apologies to Jeremy Ireland for slightly dodging his difficult question). I'll respond to the questions posted by email, and then write up some further ideas.

Something that I realised during the talk was that I am talking about a "radical democracy" made possible by various technical, social and economic development - the notion being that the separation between users-consumers-suppliers-manufacturers-designers is being eroded, and that design agency is being dispersed throughout these networks of actors. We just need to help people to develop the right kinds of theory - one in which "design thinking" is understood to be a shared capability and activity, rather than the preserve of a specialised elite.

Firstly, here's the slides and script. Then at the end of the entry, i add a video of my presentation recorded using my new Apple Podcast Producer 2 server and a MacBook.

Pedagogy of the Artificial, a talk given at the Café Scientifique in April 2010

I’ll start with a quote from the design thinker, Bruce Mau:

My research is about deliberate positive durable change: innovation. In higher education, in every aspect of higher education, ranging from the first year undergraduate performing a seminar presentation for the very first time, up to the foundation of a new university, and across many points in between: a group of researchers writing a funding bid, a library creating a new open learning space, a teacher adopting a different method, a doctoral student synthesizing half a year’s work into a ten minute presentation.

Common experiences and patterns of behaviour recur at all of these diverse points, and are transferred between them.

For the people embroiled in these changes, what might seem to others to be trivial is in reality a matter of what Mau calls “massive change”. That doesn’t necessarily mean revolutionary global change, but rather change that passes across a threshold and becomes irreversible.

Or, as is often the case, the result is paralysis, indecision, confusion, lost opportunities, lost insights, repetition, and dead-ends.

Some such changes are deeply problematic. for example the zones of transition between stages in an individual’s academic career.

Often we face what the design theorist Hors Rittel famously termed “wicked problems”. Richard Buchanan defined such cases as:

“a class of social system problems which are ill-formed, where the information is confusing, where there are many clients and decision makers with conflicting values, and where the ramifications in the whole system are thoroughly confusing”. (Buchanan, 1992: 15)

As designers have started to address issues of quality enhancement and process innovation in areas such as health care, education, welfare and government, our understanding of just how wicked these problems can be has grown - complex feedback loops between the definition of success, stakeholder perceptions and capabilities, resulting in chaos or more often paralysis - a failure to get beyond grand schemes or an obsession with optimization (Six Sigma).

Universities are, perhaps more than any other social institution, intensive sites of metamorphosis. Universities problematise and disrupt to discover and create. They are full of “wicked problems”. They seek “wicked problems”. Through exercising these capabilities, millions of people become more effective agents of change, both personal and collective.

That’s fascinating. And there’s a lot to learn from it.

We can also learn from new techniques developed by the design industry to help tackle “wicked” problems in other fields. Bringing such techniques to higher education is my chief concern.

However, for this to be possible, we must be prepared to accept two things:

1. design is more than decoration;

2. and the radically democratic idea that everyone can be a designer.

Let’s now move on to a second statement about the nature of design, this time from the sociologist Bruno Latour (famous for his studies of research scientists):

This is taken from a fascinating paper entitled “A Cautious Prometheus? A Few Steps Towards a Philosophy of Design” presented at a meeting of the Design History Society.

Latour argues that “design” is a philosophically important concept, marking out the activities and practices involved in creating the artificial. ‘Artificial’ is not a negative term, opposed to the natural. Rather, ‘artificial’ refers to inventions through which humans and human-invented entities can evolve with nature, both in nature and beyond. Design also has a duel relationship with time. Design thinking, for Latour, says of the world:

“it will neither be modernized, nor will it be revolutionized” (Latour, 2008: 3)

It will be adapted, designed.

The concept of “design” and the “designer” emerged in the early seventeenth century, as it became possible for a single person to conceive of designs implemented across the full range of crafts and objects. The power of this idea is being reinvigorated to similarly exciting ends, but with a new ingredient: the power of the designer is dispersed, aided by technology and social mobility, into networks of people - often people who would not normally consider themselves to be designers.

There are three ways of interpreting this reinvigorated design capability.

Modernist eyes see a world of obsolete people and things to be re-engineered to meet the needs of the new normative now. Revolutionary thinking looks to change everything so as to remake itself and the world. Design thinking is different. It aims to achieve innovation through a modesty, a mastery of detail and what Latour calls a “semiotic skill”. Most importantly, Latour says, “it is never a process that begins from scratch: to design is always to redesign.” Design has one eye on finding the valuable in the present and past and another on inventing new value.

That’s the theory.

Now for the practical.

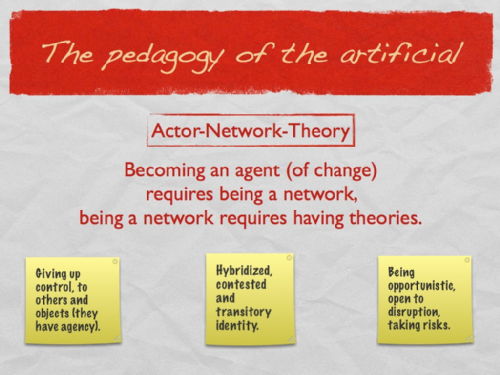

In his book Reassembling the Social, Latour re-analyses the ingredients of social change. This is in essence a lesson in creating the artificial.

He gives the formula: actor dash network dash theory. Three essential elements. Each of equal importance. Note that the second dash, indicating that theory is part of the same assemblage as actors and networks, is important and often overlooked. Theory is part of, immanent to, the world of actors and networks.

Three interconnected elements, each necessary for change to be possible. The formula may be expanded as:

Becoming an agent (of change) requires being a network, being a network requires having theories (about other agents and the network).

But each of these steps is a great challenge. Networks are unstable. Theories contested. Being an ANT, as Latour says, requires:

Giving up control, to others and objects (which themselves have agency).

Adopting hybridized, contested and transitory identities.

Being opportunistic, open to disruption, taking risks.

As a teacher, I recognize these challenges as amongst the most difficult and most essential facing every student.

Independent of all the theory, the IDEO design company has come up with a set of strategies for getting collaborations of diverse design stakeholders to take just these risks.

Tim Brown explains how design thinking adopts...

”An inherently shared approach, design thinking brings together people from different disciplines to effectively explore new ideas—ideas that are more human-centered, that are better able to be executed, and that generate valuable new outcomes.” (Brown, 2008)

Key to their success is a clearly signified separation between “inspiration” activities that expose participants to disruption and complexity, “ideation” activities through which discoveries and theories are synthesized into testable lo-fi prototypes (the slogan is “build to think”), and “implementation” activities that see the creation of shippable end products. Time and space is given for becoming collectively concerned, and for creating and testing theories or models.

Brown describes how this translates into a set of design spaces:

“The design process is best described as a system of spaces rather than a pre-defined series of orderly steps. The spaces demarcate different sorts of related activities that together form the continuum of innovation.”

A design team is encouraged to move freely between the spaces, aiming to move more towards the “implementation” space as certainty and consensus emerges.

How might this approach help students and teachers, for example, in becoming creative, forming their own projects and theories? How might it help individuals and collectives in higher education to redesign what they do?

And here is a video recording of my talk:

Robert O'Toole

Robert O'Toole

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading