'Following Living Things and Still Lifes in a Global World': Reflections on the conference

Writing about web page https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/hrc/confs/flt/

In this post, Cheng Heand Camilo Uribe Bottalook back at and reflect on their conference 'Following Living Things and Still Lifes in a Global World', which took place in mid February.

Figure 1 Olaus Magnus, Carta marina et descriptio septentrionalium terrarum (Marine map and description of the Northern lands), 1539, source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Carta_Marina.jpeg

The first panel centres around the way of approaching materials, and involves various kinds of materials including artefacts, plants and animals. The first paper by Erika de Vivo unfolded the cultural construction of Sámi people during the contacts between Sápmi (ancestral homeland of Sámi in Northern Fennoscandinavia) and Italy between the sixteenth and early twentieth centuries. The second paper by Jaya Yadav traced the plantation of Darjeeling tea in British colonial trade and its re(creation) of identity till today. The third paper by Charlotte M. Hoes looked at animal trade particularly through an animal trading company in Germany in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The three papers cover quite different subject, geography and time period. What amazed us is that they focused on a single type of material and their mobility. This means not only to be object-focused but also to follow their life from the start of the interaction between them and human beings, to their movement (materials might be moved physically and represented in different contexts via different media) and how their meanings changed during their life paths.

Apart from the mobility that all three papers emphasise, there was another important question particularly discussed in the Q&A session: how to determine the line between ‘live’ and ‘still’ materials, or, is it worth classifying materials this way? This is especially representative in the case put forward by Erika, that human remains are apart of materials that contributed to the shaping of the images of Sámi people. This also applies to tea and animals, especially when they became artifacts or products. The agency of materials is always an interesting aspect to consider when it comes to interpreting their meanings. In short, the first panel set a good start for the following discussion and sharing of ideas.

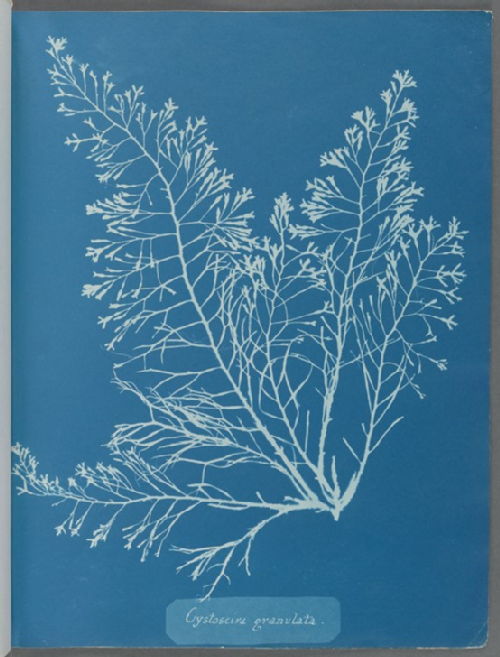

Figure 2 Anna Atkins, 'Cystoseira granulata',1844-45, in Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, The New York Public Library Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-4b02-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

In the afternoon, we started with Panel 2, which took a further step from panel 1, with three papers looking at plants only. The first paper by Anna Lawrence explored the cut-flower trade in the nineteenth-century Britain, focusing on the life of flowers before and after becoming commodities. The second paper by Annabel Dover looked at the first photographic book that contains 411 contact prints of algae collected by the botanist and photographer Anna Atkins (1799-1871) on the Kent coast and was published in 1843. The last paper by Maura C. Flannery looked at the Sicilian botanist Paolo Boccone (1633-1704), who developed techniques for making nature prints from the specimens.

All three papers touched upon the question of the relation between the plant itself and its visual representations. This is connected with one of the aspect that the conference concerns: are the material and its visual representations always discrete? These papers provided excellent examples showing that the line between the two could be blurred. Another point that the papers shared common ground with each other was the blurred boundary between the identity of the plant as a living thing in nature or as an artefact that involves human intervention. And similar to the papers in panel 1, this is related to the mobility of plants, in the sense that different stages of a plant’s life provide flexible space for assigning meanings.

The conference continued with the Panel 3, the last one, with three papers looking at animals and its different representations and interactions with humans, both in a living and in a “still-life” state. The first paper by Amanda Coate followed the life and death of an elephant in Britain and Ireland in the Seventeenth century, focusing on the animal-human relations and interactions. The second paper by V.E. Mandrij looked at the artistic production of artist Otto Marseus van Schriek and more specifically in the technique of butterfly imprints and the collecting, trading and scientific activities related to this. The last paper by Catherine Sidwell looked at the representation of birds in the British domestic interior design during the Victorian era and the different uses of their feathers, forms and colours.

Figure 3. Otto Marseus van Scrieck. Forest still-life with butterflies, snake, frog and dragonfly. 17th Century. Private Collection, Switzerland. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Otto_Marseus_van_Schrieck_-_Forest_still-life_with_butterflies,_snake,_frog_and_dragonfly.jpg

The three papers had in common that they took an animal as the starting point of their analysis: elephants, butterflies and birds. But they developed their arguments through different paths, presenting distinctive approaches to the living and still state of animals when their histories intersect with humans, whether alive, death or in a represented form. These papers provided an excellent analysis of the other-than-human and human interactions in what Amanda Coate called a “shared space” between species. This panel also versed about the agency of animals and how their presence in human everyday life evidenced interactions and connections in different contexts. In this panel, a topic that was widely discussed was the nature of an animal, living and dead, and its transitions between one state and the other, from a scientific object to an artistic one and the conditions in between. It revealed the complex nature of animals and our relations with them.

Finally, the conference ended with a keynote by Professor Helen Cowie about two anteaters in Madrid and London between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Cowie’s approach to these two animals from an animal biography perspective did a great job creating synergies with some of the main ideas that were discussed by the different papers in this conference. Although the arrival of both animals to Spain a Britain took place under different circumstances and different societies, their presence in Europe represented a living ambassador for animal species little known in Europe and triggered thought-provoking debates that Professor Cowie addressed in her presentation.

Assessing the receptions of these animals in Spanish and British societies, Cowie considered their broader cultural and scientific contexts: the logistics of the animal trade, the Transatlantic network that permitted the anteaters and the knowledge about them to cross the Atlantic, the technologies of representation that permitted to reach different audiences. Finally, Cowie’s presentation enlarged the debates that were part of this conference to colonial and imperial science, knowledge and authority.

Figure 4. Rafael Mengs Workshop (probably Francisco de Goya). His Majesty’s Anteater. 1776. Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales. Madrid. https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/la-osa-hormiguera-de-su-majestad-18th-c/YAEuV7WNHQeoYg

David Lambert

David Lambert

Loading…

Loading…

Add a comment

You are not allowed to comment on this entry as it has restricted commenting permissions.