Hangzhou International Congress

The above picture is the presentation of the ‘Hangzhou Declaration’, at the Dragon Hotel in Hangzhou on Friday 17th May (the figure to the left is Charles Landry). Why Hangzhou? Part of the rationale for holding the Congress here, no doubt, is that Hangzhou is a Creative Cities network city (for Folk arts and Crafts). And in Chinese history it is of some significance, affectionately referred to as ‘Paradise on earth in China’. The city is divided by the Qiantang River, on the north side of which is the great ‘West Lake’, now on the UNESCO World Heritage list. The said declaration was constructed after three days of plenary speeches, lectures and workshops, and is addressed broadly to governments, global civil society and the private sector around the world, but specifically to the UN General Assembly. It demands, (on the basis of amassed evidence and cases from around the world), that ‘culture’ (the arts, media, crafts, heritage, creative industries) must become internal to global economic and social development. The implication, also, is that ‘culture’ should become useful and open to engagement with government agencies, NGOs, and companies in addressing global issues that have local impact. These include environmental sustainability, poverty, and social inclusion.

The Hangzhou International Congress was sub-titled ‘Culture: Key to Sustainable Development’ and organized by UNESCO and hosted by the Chinese Government. I arrived on the 11th and left on the 18th, so either side of the 4-day conference I had a little time to catch a glimpse of how China had changed since I was last there about 8 years ago. The experience as a whole was tremendous, and I encountered dozens of fascinating people involved in a large range of development and cultural projects (from Africa to Latin America, to the South Pacific). Part of my purpose for being there was to network for my new MA and research project in ‘arts, enterprise and development’ (and it must be said, I was ‘representing’ Professor Oliver Bennett, who was the original invited delegate: this was a closed Congress). The Congress was mostly populated by directors of NGOs, government delegates or ambassadors, with notable guests such as his Highness the Aga Khan, H.R.H Prince Sultan bin Salman Abdulaziz, Liu Yondong, Vice Premier of the People’s Republic of China, and the Mayor and Deputy Mayor of the city of Hangzhou (each of these giving substantial talks on culture and development strategy in their sphere of influence).

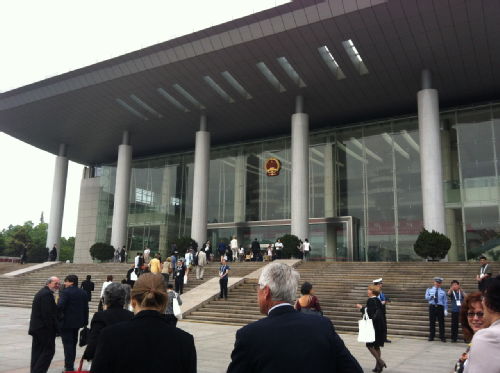

The first part of the first day was full of plenary addresses, and situated in the grand Zhejiang People’s Great Hall (photo below). The rest of the Congress was at the Dragon Hotel. The City of Hangzhou were generous hosts, and I overheard UNESCO administrators citing this as one of the best organised events they had ever attended. My favourite moment was driving through rush hour in the convoy of VIP coaches, the police halting all the traffic and pushing the countless commuters back…Not an experience a humble academic gets all too often in a lifetime. The following day was full of workshops, which is where the real debate, (and a lot of fascinating case material), emerged. It was all the more interesting to be at a global event not dominated by the US and UK, and where small states or regions had a real impact on the debate. I attended parallel sessions on culture and social cohesion, culture and poverty, culture and local governance, culture and the economy. I met with Justin O’Connor a few times, and had some productive discussions on our Monash alliance. I also spend a good deal of time with Daniel Gad of Hildesheim University discussing potential collaborations.

As to the issues: I found UNESCO’s general case compelling, and reading through their newly published (and well-designed) catalogue of evidence [Culture and Development Knowledge Management, UNESCO 2012, which presents cases from the so called MDG-F project that started in 2006 – the Millennium Development Goals] they are injecting a political imperative into national cultural funding. I await to see what happens, and how national aid budgets and the large development programs respond. Potentially it could mean a massive increase in funding for the arts and culture globally. But…..it’s a two way street, of course. Consider some of the fundamental objectives expressed by the Hangzhou Declaration:

> Integrate culture within all development policies and programs, as equal measure with human rights, equality and sustainability

> Mobilize culture and mutual understanding to foster peace and reconciliation

> Leverage culture for poverty reduction and inclusive economic development

> Build on culture to promote environmental sustainability

> Use culture to strengthen resilience to disasters and combat climate change through mitigation and adaptation

> Harness culture as a resource for achieving sustainable urban development and management

There are a couple more objectives I have left out, purposively emphasising the thrust of the argument: culture is something to be used, employed, exploited, ‘leveraged’, for something else. The argument is rarely stated in terms of ‘economic development must be ‘leveraged’ to benefit local culture’, and so on. Of course, in the realpolitik world UNESCO inhabit, this is how the argument must be made. The instrumentalist trajectory of the objectives is worrying for the reasons we all know. If ‘culture’ becomes a part of international economic development funding, then that will mean a huge increase of statutory support for a lot of cultural actors, resources, facilities and new projects. It also might mean new cultural-bureaucratic formations, and enormously powerful forces coopting and distorting local and regional cultural production. On the whole, I am with UNESCO on this one – the MDG-F publication citied above demonstrates real support for both local, historical and artistic culture and democracy in equal measure. Please invite me back.

Jonathan Vickery

Jonathan Vickery

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…