All entries for May 2013

May 30, 2013

Comparing tastes in the UK and Finland

Two papers published this month, written with colleagues from the University of Helsinki, Semi Purhonen and Riie Heikkilä, and supported by the British Academy, represent the culmination of a project on comparing cultural tastes in UK and Finland.

Two papers published this month, written with colleagues from the University of Helsinki, Semi Purhonen and Riie Heikkilä, and supported by the British Academy, represent the culmination of a project on comparing cultural tastes in UK and Finland.

Why compare tastes? Principally because one criticism of the most influential account of the social patterns of taste, Pierre Bourdieu’s Distinction, is that its analysis is tied to a specific time and place and therefore its insights are not transferable to other times and places. Comparison between nations is one way to explore that further.

Why the UK and Finland? Here the answer is partly practical. Many of the comparative studies I’ve read on other topics are prefaced with accounts of their difficulty. Whilst, of course, we had our struggles, our path was eased by the fact that two studies with similar questions, methodologies and a similar relation to Bourdieu had been recently conducted in the UK and in Finland. This made comparison something of a natural next step.

The first of the two papers, written with Semi Purhonen, appears in a special issue of the journal Cultural Sociology on ‘field analysis’, edited by Mike Savage and Elizabeth Silva. Field, along with habitus and the more familiar capital is one of Bourdieu’s conceptual triad, with fields representing the overlapping spheres of human activity in which capitals are struggled over. Field, capital and habitus are always inter-related for Bourdieu – an element of his approach which is often forgotten, at least by some of his critics. In order to be analyzed fields need to be constructed or demarcated somehow – and the special issue shows some great examples of how this can be achieved, in relation to such diverse topics as comedy, fell-running and the digital worlds of musical tastes. For comparison, though – and especially for comparing something as complex and hard to pin down as ‘national taste’ - the fields that are being compared need to be constructed in similar ways. Our studies allowed that to happen, but not without some problems. These problems included how to interpret the different items which are asked about in national surveys of taste and participation, and the different positions of those items in local or national cultural hierarchies – assuming such surveys can’t just be identical (asking about schlagers in the UK would be as meaningless as asking about cricket in Finland). In the paper we explore how Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA), the statistical method which underpins Distinction -which produces those infamous diagrams and which Bourdieu describes as ‘thinking’ in terms of relation – allows a partial resolution of these issues by revealing the underlying structure of tastes. Regardless of which items or activities are liked in the two countries, the MCA produced by both projects showdivisions which can be similarly interpreted in both nations, and which relate to class, education and age. The activities themselves are less important, then, than their relation to other activities. We back this up by analyzing the in-depth interviews of people located, through their survey answers, in different bits of our national ‘fields’, so that we can explore how people feel about their likes and dislikes, illustrating how a position in a field is experienced – and importantly reminding us that people are more than an accumulation of their variables. It was an interesting process – and might provide a model for comparative work of this kind in the future.

The second paper, written with Semi and Riie, appears in the journal Comparative Sociology. Here our concern was to use taste to critically explore the notion of ‘cosmopolitanism’, which has emerged as a somewhat hopeful and optimistic form of post-national identity, characterized by tolerance and openness to difference. It is a concept which has been more theorized than empirically explored, though, and taste might be where it is visible. The value of comparison here is that, for all their similarities, the UK and Finland have distinct collective histories shaping their national cultures and are differently positioned in global flows of people and things. We used the interviews and focus groups produced by the two projects to explore how the tensions between the national and the global are played out. We find lots of examples of what the sociologist Ulrich Beck refers to as ‘banal cosmopolitanism’ – i.e. the presence in everyday life of items and people from beyond ‘the nation’, simply by virtue of the globalization of the cultural industries and migration of various forms. Interestingly we find little evidence of rejection or suspicion of ‘global culture’, or at least its US version – which might have been present in studies of this kind in the mid-to-late twentieth century. Age seems to be an important indicator of cosmopolitan attitudes – especially in Finland where learning languages, including English, appears to give ready access to work and travel abroad. In both countries, for younger more educated, professional groups (those with, roughly, more cultural capital), identifiably ‘national’ forms of culture were less attractive than more exotic forms. Older people and those with lower levels of education seemed more attached to the nation (although in Finland, older people who might be identified as elite also seemed to exhibit particular pride in national cuisine). These kinds of findings might indicate some of the ambiguities of cosmopolitanism – it might spread with the cohort effect of younger generations and the inter-connections of global culture, but it is equally likely to be marked by inequalities in cultural capital, although on a global scale.

Producing both papers was a very rewarding process – and hopefully these conversations, about the UK, Finland and elsewhere, will continue.

Warwick staff and students can access the papers via WRAP

You can find links to the articles and follow my research on academia.edu

May 24, 2013

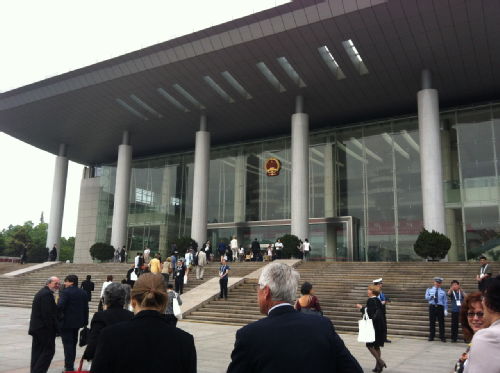

Hangzhou International Congress

The above picture is the presentation of the ‘Hangzhou Declaration’, at the Dragon Hotel in Hangzhou on Friday 17th May (the figure to the left is Charles Landry). Why Hangzhou? Part of the rationale for holding the Congress here, no doubt, is that Hangzhou is a Creative Cities network city (for Folk arts and Crafts). And in Chinese history it is of some significance, affectionately referred to as ‘Paradise on earth in China’. The city is divided by the Qiantang River, on the north side of which is the great ‘West Lake’, now on the UNESCO World Heritage list. The said declaration was constructed after three days of plenary speeches, lectures and workshops, and is addressed broadly to governments, global civil society and the private sector around the world, but specifically to the UN General Assembly. It demands, (on the basis of amassed evidence and cases from around the world), that ‘culture’ (the arts, media, crafts, heritage, creative industries) must become internal to global economic and social development. The implication, also, is that ‘culture’ should become useful and open to engagement with government agencies, NGOs, and companies in addressing global issues that have local impact. These include environmental sustainability, poverty, and social inclusion.

The Hangzhou International Congress was sub-titled ‘Culture: Key to Sustainable Development’ and organized by UNESCO and hosted by the Chinese Government. I arrived on the 11th and left on the 18th, so either side of the 4-day conference I had a little time to catch a glimpse of how China had changed since I was last there about 8 years ago. The experience as a whole was tremendous, and I encountered dozens of fascinating people involved in a large range of development and cultural projects (from Africa to Latin America, to the South Pacific). Part of my purpose for being there was to network for my new MA and research project in ‘arts, enterprise and development’ (and it must be said, I was ‘representing’ Professor Oliver Bennett, who was the original invited delegate: this was a closed Congress). The Congress was mostly populated by directors of NGOs, government delegates or ambassadors, with notable guests such as his Highness the Aga Khan, H.R.H Prince Sultan bin Salman Abdulaziz, Liu Yondong, Vice Premier of the People’s Republic of China, and the Mayor and Deputy Mayor of the city of Hangzhou (each of these giving substantial talks on culture and development strategy in their sphere of influence).

The first part of the first day was full of plenary addresses, and situated in the grand Zhejiang People’s Great Hall (photo below). The rest of the Congress was at the Dragon Hotel. The City of Hangzhou were generous hosts, and I overheard UNESCO administrators citing this as one of the best organised events they had ever attended. My favourite moment was driving through rush hour in the convoy of VIP coaches, the police halting all the traffic and pushing the countless commuters back…Not an experience a humble academic gets all too often in a lifetime. The following day was full of workshops, which is where the real debate, (and a lot of fascinating case material), emerged. It was all the more interesting to be at a global event not dominated by the US and UK, and where small states or regions had a real impact on the debate. I attended parallel sessions on culture and social cohesion, culture and poverty, culture and local governance, culture and the economy. I met with Justin O’Connor a few times, and had some productive discussions on our Monash alliance. I also spend a good deal of time with Daniel Gad of Hildesheim University discussing potential collaborations.

As to the issues: I found UNESCO’s general case compelling, and reading through their newly published (and well-designed) catalogue of evidence [Culture and Development Knowledge Management, UNESCO 2012, which presents cases from the so called MDG-F project that started in 2006 – the Millennium Development Goals] they are injecting a political imperative into national cultural funding. I await to see what happens, and how national aid budgets and the large development programs respond. Potentially it could mean a massive increase in funding for the arts and culture globally. But…..it’s a two way street, of course. Consider some of the fundamental objectives expressed by the Hangzhou Declaration:

> Integrate culture within all development policies and programs, as equal measure with human rights, equality and sustainability

> Mobilize culture and mutual understanding to foster peace and reconciliation

> Leverage culture for poverty reduction and inclusive economic development

> Build on culture to promote environmental sustainability

> Use culture to strengthen resilience to disasters and combat climate change through mitigation and adaptation

> Harness culture as a resource for achieving sustainable urban development and management

There are a couple more objectives I have left out, purposively emphasising the thrust of the argument: culture is something to be used, employed, exploited, ‘leveraged’, for something else. The argument is rarely stated in terms of ‘economic development must be ‘leveraged’ to benefit local culture’, and so on. Of course, in the realpolitik world UNESCO inhabit, this is how the argument must be made. The instrumentalist trajectory of the objectives is worrying for the reasons we all know. If ‘culture’ becomes a part of international economic development funding, then that will mean a huge increase of statutory support for a lot of cultural actors, resources, facilities and new projects. It also might mean new cultural-bureaucratic formations, and enormously powerful forces coopting and distorting local and regional cultural production. On the whole, I am with UNESCO on this one – the MDG-F publication citied above demonstrates real support for both local, historical and artistic culture and democracy in equal measure. Please invite me back.

May 06, 2013

CBS Seminar and Book Launch

Friday 3rd May I was at Copenhagen Business School, where I had arranged (with colleague Ian King) a seminar to launch our edited book. CBS is such a great place, and is probably the only university (not just a ‘business school’) with a critical mass of researchers who work across creative practice, aesthetics and management and organization theory. CBS has been a guiding light in some of our past projects, particularly our friend and mentor Pierre Guillet de Monthoux.

The book – called Experiencing Organisations: new aesthetic perspectives – was officially published a few days before, and a number of people who contributed to the book were there (with extraordinary serendipity, two contributors from the US were visiting CBS along with friends from York, Portugal, Paris and Stockholm). We decided, given the distance, that the book launch should be more of a seminar than a drinks and book sale. We therefore arranged six of us to speak and I previewed some video footage I had shot as part of the last Art of Management and Organization conference (York University, last September). Our purpose for the launch was to consolidate our small network, through which information about the book can travel into the market; so we only planned for about 30 people maximum. The day started at 11am when people started to arrive, and finished around 4pm.

The presence of Stephen Linstead from York was significant. He was combining the book launch with a meeting with CBS, who are hosting the next Art of Management conference in September 2014. In the last few months, the conference, along with the journal Organizational Aesthetics (run by playwright and management prof. Steve Taylor from the USA) has become incorporated as a non-profit company. I have been asked to be the Chair. This venture is satisfying given that it has effectively emerged as the new incarnation of The Aesthesis Project ran by Ian, me and another colleague, the first conference starting in 2002. It is going to be very interesting how this new venture will expand internationally.

The day started with Ian narrating the historical of the development of the Aesthesis Project and how the book emerged from that. I then gave my address, which was partly an account of the book and partly a reflection on my chapter: [which I will post on my research page.]. We then had a short talk from the publisher’s MD, Paul Jervis, who demonstrated his commitment to the book by being present on the day. The next talk was Chris Poulson, management professor emeritus as well as photographer, whose animated talk worked his way through the thirteen photographs he published in our book. Steve Taylor, who both announced a few things about the journal and gave an overview of his theory of leadership, reflecting on his own chapter (written with artist, Barbara A. Karanian). A CBS prof, Per Darmer, along with Steve Linstead gave a short talk on the development of the AMO conference, at CBS in 2014. I then concluded the day by showing an edited series of clips from the AMO at York last September. I returned to one of the themes of the York conference (on using documentary film as a research tool), but in the context of disseminating knowledge of the conference beyond the usual formats of proceedings and/ journal articles. How can documentary be used to disseminate the knowledge acquired, learned or accumulated, at a conference? I shot the film simply as a way of experiencing the problems of documentary film in a research conference context, particularly where research involved creative practice. The conference has a theme, but constructing a narrative from footage as I walked through dozens of streams and parallel seminars, was very difficult and I don't think I managed it. We are now thinking of a more serious and strategic approach to the CBS event in 2014. And for the book, I am going to put together a short promotional video, using some of the footage.

David Wright

David Wright

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…