All 66 entries tagged Warwick University

View all 301 entries tagged Warwick University on Warwick Blogs | View entries tagged Warwick University at Technorati | View all 3 images tagged Warwick University

May 26, 2006

Podcasting, seminars and e–portfolios

Last night I recorded a seminar as part of the What Is Philosophy? project. During the seminar discussion, I made some comments that I suspect may play a key role in my research. It took just a few minutes to edit my comments and the subsequent discussion into a small file, and upload it into my eportfolio and blog. You can listen to this by clicking on the button below:

This gave me a thought:

Perhaps in the near future, as e–portfolios become more common within higher education, amongst the various snapshots of a student's academic work, we will see podcasts of seminars.

May 25, 2006

E–learning Research: a Deleuzian method for the evaluation of virtual learning environments

VLE

A series of questions must be addressed:

- What is an environment composed of?

- What varies between different environments to create differing environmental regimes?

- To what extent is a virtual learning environment (VLE) an environment?

- How do VLEs vary, so as to create different regimes?

- Are certain such regimes preferable to others?

Environments are composed of filters

In this way behaviour and geophysical processes connect through an environment that is the assemblage of all of these interoperating filters over time. This is more or less true of any environment. The physical built environment is well understood in these terms, but also consider how an online application with a variety of user accessible functions filters a pool of back–end functionality. In return, the end user filters out irrelevant or inaccessible functionality. Over time these functions may even die off through lack of interest or the application of an agile development process that in some ways copies evolution.

The case of the polar bear is presented above in a simplified manner. There are many complications and possible combinations of filters that offer other kinds of environmental regime. Reality presents a range of regimes and blends of regimes, many of which occur across widely differing regimes. For example, in his work on the 'extended cognition' model of cognition, Andy Clark proposes that a kind of mangrove effect may well be a significant assemblage in the generation of new ideas. Clark describes how a new mangrove swamp begins by a single plant floating in the water, with extended roots that may catch hold of both food and other plants. This kind speculative drift is another assemblage of filters that may be a viable regime in some environments. For example, in the online world we may use a blog to float a part–formed notion. Effective use of semantic tagging and discovery tools may attract further content to the idea, allowing it to grow. It may also allow it to connect to other complimentary ideas. Over time as the mangrove–idea grows, it attracts further connections and taps into greater pools of energy.

The mangrove is an example of a regime of filtration that the philosophers Deleuze and Guattari have called rhizomatic. There are many other regimes, many of which are diagrammed in their book A Thousand Plateaus. These regimes include arborescent assemblages, which operate by applying rules of exclusion that form hierarchical branches of filtration; a familiar model in both software design and social anthopology. Other regimes of importance include:

- Gadgets, or filters that follow a reproducible and generalizable design;

- Animal bodies (which are gadget–like, but less portable and generalizable);

- Familial structures;

- Mythologies;

- Geological and sedimentary processes.

We therefore have the first of our tools for understanding the construction of environments: regimes of filtration. As has been demonstrated, the principle applies across environments, and in some cases we see regimes re–occurring in quite different settings.

Environments are composed of networks

A second and relatively rare aspect of some environments can best be understood through the behaviour of a more complex animal: the honey bee.

Karl von Frisch

Waggle dance, plume theory, filters

James Gould Cognitive map

Abstraction

some filters are symbolic or digital, redundancy

codings to promote autopoiesis through symbiosis

simulations to accelerate judgement

dissimulation to exploit weaknesses in the simulations of others

the relation between filters and networks is a matter of ecology

Environments are actual

quantification and index

registers of modification

progress

the actual tends to impose limits on differentiation

Environments are virtual

signal can be quantified, the carrier (the assemblage of filters) is more complex and sensitive – a continuum

movement, freedom, creation

whole system evolves continually

different elements evolve at different speeds

differential speeds provide registers for understanding the different elements

Smooth and striated space

Emergent actuality

Instructional VLEs

Research VLEs

May 24, 2006

How to write a communications strategy

Purpose

One of the key aims of a communications strategy is to ensure that the best 'channels' of communication are used for each of the different 'stakeholders' with whom one must engage. The use of inappropriate channels is a common and sometimes serious mistake. For example, I do not wish to be told by my doctors surgery that I must use an online diagnosis form, I want to actually talk to a real person. Unbelievably, the obsession with technology has actually caused such obvious errors of judgement. One must think carefully about audience, and match channels to them carefully.

Stage 1: stakeholders

The first stage of the process is to identify the range of "stakeholders" with whom communication must be carried out. There may be some groups within the university for whom this is straightforwards. However, I suspect for the majority there are a range of different and sometimes conflicting groups to be catered for. So what of the E–learning Advisor Team? Consider our rather broad and general aim: to encourage wider and more effective use of learning technologies throughout the four faculties. Obviously the agents of this change are our principle stakeholders. But we should also consider everyone who will beneift, as they are ultimately those who will judge our effectiveness.

Casey provided us with A3 sized grids on which to record our ideas. Along the vertical axis, we listed each of the stakeholder groups. On my grid I added the following:

- Lecturers - techies and early adopters. Lecturers who are prepared to adopt new learning technologies without much prompting or convincing. This group presents us with an easy but not necessarily significant or sustained win.

- Lecturers - followers. Perhaps an unfair description, as the majority of lecturers simply do not have a great deal of free time to try out new approaches. They have to use well tested and understood techniques.

- Lecturers - resisters. This group actually puts effort into opposing the introduction of new learning technologies, even though no one is actually forcing them to do anything. Yes, they really do exist, and can exert a formidable effect within departments.

- Graduate research students and post-docs. A group that I take very seriously. They do a big share of the teaching, as well as being users of learning technologies for private study.

- Taught students. There is some controversy about whether we need to communicate with taught students. It could be argued that this is the responsibility of the relevant lecturers. However, I believe that it is necessary and valuable for us to work directly with taught students. At Warwick we aim to encourage students to act independently, taking personal responsibility for their skills and technologies. The Learning Grid is a brilliant example of this approach.

- Departmental IT. Some departments have their own IT people, who act as key agents of change (or stagnation in a few rare cases). This is more common in the Sciences.

- Departmental administrators. Another significant set of agents for change. The Business School's e–learning team had a strategy of working closely with administrators. This is said to be a very effective approach, leading to excellent integration of admin and e–learning systems, something that IT Services has failed to do.

- IT Services. The people who run the services upon which we rely must be informed as to the significance and effects of their services.

- Central service providers. For example the Library and the Warwick Skills Programme, who are themselves keen to adopt the best technologies, and who may also effect change within departments as they demonstrate successful applications.

That is quite an intimidating range. Perhaps we should consider cutting some of the stakeholders out of the plan? For example, we could take the easy route and focus upon the techie/early–adopter lecturers. But then we risk alienating the vast majority of lecturers by only ever addressing the needs and interests of individuals who are already unique and eccentric. Alternatively, we could simply address the silent majority of lecturers, the 'followers'. That would be a hard and perhaps impossible slog, in which we may fail to encourage and communicate any good examples of the use of learning technologies. Probably the best solution is to prioritise, and work with each group where they offer the best strategic return.

Stage 2: channels

Assuming that we do have to communicate with each of these groups in some way, the next step in formulating a communications strategy is to consider the range of available 'channels' of communication that are available. Once that I started on this list, I quickly realised how many we do regularly use, and just how diverse they are. My list included:

- The E–learning at Warwick web site.

- Content on other people's web sites.

- The E–learning Forum.

- The E–learning Blog.

- Personal blogs.

- Email, personal.

- Email, list.

- Telephone.

- Booklets and leaflets.

- How to guides.

- Flyers.

- Posters.

- Billboards.

- Personal contact.

- Coaching sessions.

- Presentations within other meetings.

- Seminars and workshops.

- Conferences.

- Novelty items (I mean fridge magnets, drinks mats etc).

I'm sure there are even more, but I ran out of room on the A3 grid, upon which they were plotted along the horizontal axis.

E–learning Team Comms

Now, with the stakeholders and the channels plotted, one can consider matching the latter to the former, that is to say, ensuring that the appropriate channels are used with each group of stakeholders. This immediately throws up some key issues. For example, I expect that content presented via blogs could be more accessible and interesting to undergraduates. However, I have in the past made the mistake of expecting a moderately 'resistant' lecturer to read a blog! My experience is that such people actually expect and demand to be dealt with on a personal face–to–face basis.

Thanks Casey!

April 20, 2006

E–learning Research: tuition fees, market differentiation, and the role of e–learning

It is unusual to see full-frontal nudity in the pages of the Daily Telegraph. Even more shocking that the model in view should be a dear old friend. Unfortunately, this Monday (17–04-06 – abbreviated online version available), there seemed good reason to laugh at the indelicately exposed flesh of that alleged emperor of the education world: the British Arts Degree. The claimed justification for this sudden revelation? They want to charge £3000 a year for the privilege. The ever to be trusted investigative methods of the Telegraph hacks are ringing the first of what will be many alarm bells. They are asking: £3000 for what? Six hours of lectures and seminars a week for someone studying History at York. Outrage. Eight hours a week and you get a psychology degree from Bristol. Even the old Freudster couldn’t have dreamt up that one.

The story was all too superficial, but let us put that aside for a moment and consider the implications of the article’s underlying perception for Warwick. Then it will be possible to consider what this may mean for e-learning.

Firstly, I am a new father, already contemplating university fees eighteen years from now (I am absurdly long sighted). The effects of tuition fees on my considerations are: for that kind of money my son could go anywhere. That is certainly not true, I imagine that a good American education is significantly more expensive. But I have the modern British attitude to debt: when I pay out sufficiently large sums of money I deliberately avoid thinking about the number of zeros on the end of the sum. I’m more inclined to dream about the magnificent product that I am buying. The consequence of this deliberate blindness to the level of my personal debt is that I do not notice whether I am spending £3000 or £10000. For evidence, consider my mortgage, a staggering and entirely unreasonable amount of money. Therefore, if I have to pay out lots of cash for my son’s education, I will go for the best available, or at least as much as my credit limit can handle. And if that also means he gets to go abroad, somewhere nice for me to visit, why not? Perhaps what will happen over the longer term is that the portion of an individual’s debt available for house-buying will decrease, whilst the portion to be spent on education will increase. A £20,000 decrease in money available for the mortgage is quite insignificant. Moving that £20,000 into the education debt would make a very big difference. Even so, America may still seem just too expensive, but then there are plenty of alternatives. Australia for example is a dream for many young people in Britain, and they do actually have some decent universities. Perhaps we should set up a campus in the Pacific? In any case, now that I am a consumer of higher education, with money (or rather debt) to spend, I feel more financially empowered than I was as an undergraduate in 1991 having my fees and rent paid for me. That empowerment makes me think: what cool things can I get for my money? Expect to see the appearance of a magazine title just for people like me: Which University?

The implication of tuition fees for Warwick? Undergraduate degrees are now placed into a complex and global market. After years of trying to stay ahead of the other First Division Russell Group universities, with a distant hope of promotion to the Premier League, the game will suddenly change altogether. At the very least the range of feasible and thinkable options available to the school leaver will grow (despite the current number of institutions, there are still very few genuinely different options for the aspiring middle class kid). Competition between the providers will increase. The need to differentiate the product will become pressing (already noticeable in the proposed new Warwick Learning and Teaching Strategy, which seeks to differentiate us as thoroughly “innovative”). The market (or at least its self-appointed guardians, including the Telegraph) will seek out variables of comparison between the products on offer. For example, it is possible to compare the amount of “contact time” (lectures, seminars etc) that a student gets for their £3000 at the various institutions. The Telegraph have done just that. Expect a league table of contact time to be published very soon.

Students and their parents have always had their own methods for comparing universities and making choices. At the first stage of consideration the decision is made for them: which of the various leagues are they in: Oxbridge? Red-brick? Polytechnic? A small minority of students will then base their choice on the specific details of the courses on offer. Students with minority interests (theology, anthropology) will have little choice. For the majority of students, the next most significant consideration is lifestyle. Campus or town based? By the sea? Big City? Near to home or far away? Lively Student’s Union? Nightclubs? Girl-to-boy ratio? The choice has always been taken lightly in academic terms but with huge significance in the social aspect. Perhaps this will remain the case. The current orthodoxy claims that the typical undergraduate wants a degree course that simply offers them the required sheet of paper bearing the figure “2.1” along with three years of fun and “personal development”. In this case the terms of the competition are simple: which university can guarantee the 2.1 whilst offering the best social experience? I contend that Warwick may well lose out to Sydney in the second of these variables. For now the guarantee of a safe degree result may override this. But as the members of this globally scoped market wake up to the new competition, they may well all start to focus their energies on the guarantee of reasonable academic success. In which case who wins? Sunny Sydney with its glorious beaches and bronzed bodies? Coventry? Expect to see the Which University? guide looking ever more like a holiday brochure.

Some will of course dissent from this trend. Perhaps in eighteen years time my son will realise that he is to be expelled from the family home and packed off like a convict to the land of Oz. I will seek at every opportunity to instil him with a sense of adventure, but should that fail, he may oppose my plans by opting to join the thousands of young people who simply choose not to go away to university (he can stay, but will have to live in the garage). The Open University is increasingly popular, as are the many smaller more local universities offering easier and more certain access. This is in many cases a rational choice, not just for economic reasons. Many students simply cannot cope, at 18, with leaving home. The OU may be the best thing for them (note, I came to Warwick at the age of 20). Expect the appearance of a league table of drop-out rates and mental health problems to be published very soon, as the consumers wise up to this being an important consideration.

The traditional market for universities like Warwick would then be significantly eroded in two directions, with some students globalising, whilst others become even more sedentary. In either case Warwick seems to lose its footing. We can attempt to combat this with glossy brochures and friendly open days, but as competition becomes more intense, and the market more discerning, the bottom-line story will come under closer scrutiny and really must hold up effectively. And all the time every other fish in the pond will offer a pretty picture of nice residences and a lively social life. Such things cease to be a differentiator and instead become commodified.

These trends will no doubt be the certain outcome if consumer attitudes remain as present. But the Telegraph article may indicate (or be leading) a significant shift. At least a large sub set of consumers will start to behave more intelligently, with a detailed appreciation of what makes the difference between institutions and their offerings. Expect, at least in the short term, a rise in the number of courses that combine the safety of a traditional UK institution with more exotic destinations abroad (these are already a big part of the Arts at Warwick). Also expect to see prospective students seeking clarification and verification of claims by British universities that they offer a special kind of educational experience, somehow resulting in superior graduates. What exactly is it about a degree at a certain institution that makes it worth the money more than any other? This is the real drive behind the Telegraph article.

The obvious claim is that limited contact hours equal poor quality education, and vice versa. This is countered with the notion that arts students benefit greatly from even a small quantity of high quality contact with top experts, whilst developing independent skills of their own: so called “research based learning”. This is in many cases the “exactly” of “what makes a specific degree better”. I have heard this argument at Warwick, and indeed have on occasion used it myself. Unfortunately as a differentiator and mark of quality, this concept has become dramatically devalued and will not stand up to the kind of scrutiny applied by the Telegraph. Professor Anthony King of Essex University knows this to be the case. He makes the obvious point that 18 year old students do not have the required skills to operate as independent researchers. Expect to see as a consequence universities differentiating themselves through well worked out, consistent and clearly branded undergraduate induction and skills programmes. Warwick MUST do this to keep competitive as an undergraduate provider. However, such curriculum developments are expensive. And the question of who bears the cost has to be settled. It may be born by agencies external to the subject specialist academics, by for example a central undergraduate skills programme separate from academic departments. However, we then risk the dilution of the degree programme away from subject specialism and academic expertise, precisely the things that we claim give its special value. At the other extreme, the cost of curriculum development would fall upon the subject specialist academic. This would be a difficult choice at a time at which increasing pressure is being placed upon such academics to produce high quality work to be evaluated by the Research Assessment Exercise. It may be that research academics simply cannot do the extra work of redeveloping the curriculum at this time.

The immediate quandary facing Warwick, given the changing market conditions, is then how can it differentiate its undergraduate offerings with some special characteristic, such that its claims:

- are significantly attractive to prospective students within a global market;

- represent value for money;

- can be understood by prospective undergraduates (and the media that tells them what matters) without too much effort;

- do not add an unbearable overhead to existing resources (academics);

- can be maintained as a distinct advantage over the competition for a significant length of time.

By definition, there is no simple solution. If points 1 to 4 were easily achievable, then every one of our competitors would achieve them right away, leaving us with no advantage: we would fail on point 5. As always, any solution to the problem of successful differentiation in competition requires a blend of strategies that:

- meet the popular demands and expectations of the market;

- do so in some uniquely special and un-commodifiable way;

- reduce cost whilst bringing new value to all participating agents.

At this point the common reaction is to reach for a copy of the Oxford Dictionary of Techno Wizardry. Look under E for E-learning perhaps. But don’t get too excited. There are some possibilities, but we will not find a panacea. Technical solutions can only be part of the answer to the kind of problems that I have outlined. For example, we could create an online induction course that requires no input from academic staff. However, if it worked really well and delivered valuable education, it would not be delivering an education valuable in a way specific to Warwick and its academia. In fact it would soon become commodified, copied by every other university. Technical solutions always imply that we must keep innovating and improving, as they are easily copied by the opposition. The best solution is to pair the technical solution with something else that cannot be copied by another university. Something unique and situated in the culture and community of the place, which must itself develop to meet the new challenges alongside the introduction of new technologies.

At this point I should make clear exactly what I am not advocating, for e-learning already has a bad name from the wrong kind of coupling of technological and cultural change. Many within education and beyond have sought to force change through technological development. This however very rarely works, unless you have the power to force everyone to use the new technology. Unfortunately, this tactic is usually the last resort of institutions who do not have that kind of power. Paradoxically, they hope to attain this authority surreptitiously through the introduction of technology, which of course relies on having such a degree of power (the strategy thus collapses into circularity). For example, the rapidly fading generation of Virtual Learning Environments (Blackboard, WebCT, Learnwise) have been adopted by some institutions as a means of introducing quality assurance frameworks by stealth. The idea being that the VLE “encourages” lecturers to document their teaching activities and to record the work of their students in an online location easily accessible to university authorities. Administrators would then be able to drill-down into institutions to examine every detail of what is going on, without even leaving their desks. Of course no British university has either the power or the will to force academics to cooperate. Consequently there are a lot of very empty VLEs out there.

Instead, we require a different kind of technology strategy, one that takes the best aspects of the unique community and culture of the university, and supports, enhances and extends them to provide a significantly different and more valuable undergraduate experience. Importantly, this cannot be done in isolation from development in the practices of the people involved in teaching undergraduates, as they are the key source of value. So we could see the introduction of a superb new technical tool for supporting undergraduate learning, for example a blog system, but that must be connected to and validated by the involvement of the specialist academics that are Warwick’s special value. Currently the Warwick Blogs system does give us a small advantage over our competitors in the overall undergraduate provision, but it is not in any way rooted in the academic specialism and culture that makes Warwick unique. It is potentially comodifiable. Expect to see Oxford Blogs, Cambridge Blogs and so on at some point soon. The next difficult question, one that I do not yet have sufficient answers for, is how we develop our e-learning provisions so as to stimulate the required cultural development within the university. I have a strategy, but not yet the required tactics. Any suggestions?

April 19, 2006

E–learning Research: copyright and the principle of fair dealing in education

Firstly, what is meant by "fair dealing"? The notion refers to exceptions in the application of copyright that may be claimed as applicable to specific breaches of an author or artist's rights. In a limited set of situations, one could offer as a defence in court that a breach of copyright is "fair" under the accepted meaning of that part of the copyright legislation. Whether a specific breach of the law is "fair" or not is always a matter of judgement.

What then is allowable? Under "fair dealing" it is the case that certain educational activities that breach copyright are acceptable. These exceptions are however very strictly defined. Stepping outside of the boundaries leaves one with no legal defence. The boundary is simple, as Raymond Wall explains in his very useful Copyright Made Easier (Aslib/IMI 2000): one may break another person's copyright by making a copy if that copy is to be used for either research or private study. If used for research purposes, then the copy may be circulated amongst the researchers, or they may each make their own copies. If used for private study, the copy may be used privately by a single "student":

'Private study' has become accepted as excluding group or class study… p.169

Notice that the shared use of copies in the research context does not apply to the study context. Copies cannot be made for and circulated to classes of students. This may be quite a surprise. We have become familiar with the following activity:

…someone possessed a photograph of a painting, taken for research or private study, and subsequently showed it to a class… p.273

For example, a slide of an artwork being presented to a class. And as Wall argues, we are justified in considering this not to be a problem:

…it is doubtful whether the rights owner would object… p.273

But the fact is that in doing so we have no legal right or recourse to "fair dealing". If we then seek to transfer this scenario to the digital world, making a scanned file of the artwork and "showing" it to the class via the internet, rights owners understandably get a lot more upset and a lot less charitable. Digitisation enables the rapid production and circulation of multiple copies, beyond the original good intentions of the person who originally scanned the image – bad news for rights owners. One might then consider claiming that the digitised image is circulated via the internet for research purposes and not for private study. This almost works. Unfortunately, we should remember that "fair dealing" is not a guaranteed right, but rather a possible defence that may be available if indeed the dealing were fair. However, if the digitised image were to become available beyond the research group, and multiple copies are made for purposes beyond the research, then the rights of the copyright owner have been infringed unfairly.

There is then a chain of misconceptions that lead people from acceptable fair dealing for private study or research, to the abuse of copyright online. And subsequently I must often explain that just because you can share an image for research purposes or show an image in a lecture, you cannot therefore digitise that image and put it on your web site.

Does this then mean that we can do very little with digital media? There are two further possibilities that may provide the rights to use the media. Firstly, there is the lapsed-time defence. A moderately complex set of rules governs the persistence of copyright after the creation of object or the death of the artist/author. Unfortunately this is not at all straightforwards.

In the case of an artwork, current ownership may lie with a gallery or other body that has licenced the right to make a copy to a specific person (or excluded others from the right under specific contract, such as the right of the public to enter the gallery). The person who then creates the image of the artwork then holds the copyright of the image, but under contratcual terms imposed by the gallery. When reproducing an old artwork, by for example scanning a postcard, one must respect the copyright of the person who created the image of the artwork that is being reproduced.

In the case of a sufficiently old text, although no specific reproduction of it can be copyrighted (even a different presentational form or typography), the text may contain notes or translations that are original to a more recent agent, and therefore part of their rights.

The final and most painful solution is to obtain permission, from the rights owner, to reproduce their work. In some cases, we are lucky to find that someone has already done the work for us. As Wall explains, the exclusion of group or class study is:

…in fact the basis of photocopy licensing of multiple copying in the education sector. p.170

But in many cases, including almost all digitisation, there are no such agreements or agencies. In these cases, permission must be sought on a item by item basis. You simply have to do the tedious work of contacting artists/authors and asking for permission.

Copyright is then a significant blocker to the use of artworks and texts in the arts. The assumption that such educational use is "fair dealing" is false. Without rights agreements and agencies to help, keeping legal is a difficult task. My next investigation on the subject will be to consider the agencies and agreements that are available now, or in the near future, to assist.

Comments and corrections are most welcome (especially if they are from lawyers and free of charge).

April 06, 2006

E–learning Research: Why academics blog (or not)?

Follow-up to Research Plan: ideas for researching networking, narrowcasting and broadcasting by bloggers from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

Why this matters

I think I have some answers to these questions. Or at the very least, I have a good way of thinking about the problem that may render it answerable. But first I assume you are not necessarily convinced that it matters. In response I offer two arguments:

- Answering the question of why academics don’t blog may give us a deeper insight into academic attitudes and behaviours. This knowledge is transferable to other learning technology development problems;

- I believe that weblog technology (along with other new web tools) has the potential to dramatically enhance the “academic environment”, if applied intelligently.

So there you have my agenda and motivation. I hope you agree on its significance.

Understanding the desire to blog

We should ask more widely of all bloggers: "why do you blog?”. The first and key step in answering this question is: "who do you blog for?" – "what is your intended (or implicitly assumed) audience?" The intention of a blog may be to inform, enrage, impress and so on, but those effects are always relative to and motivated by the imagined effect on a given audience. The blogger blogs so as to have these effects on an audience. Sometimes, as in a solely reflective blog, there is an audience of one, the author themselves. Even so, the motivation is to have an effect on that audience.

At this point, as I suggested in an earlier entry, we can use one of the core concepts of communications and design studies: narrowcasting versus broadcasting. The question then is put more specifically:

- Do you write for a specific actual audience (known nameable people)? – In which case you are engaging in formal narrowcasting (the most formal narrowcasting will apply privacy controls to keep unknown people out);

- Do you write for a specific virtual audience (unknown but clearly classifiable people, such as "all philosophy students")? – In which case you are engaging in informal narrowcasting.

Or:

- Do you write for no specific audience, considering your audience to be anyone who finds your blog? – You are engaging in broadcasting;

- Do you write content that appeals to a broad and loosely specified audience, but seek positive feedback from an identifiable and narrow audience? – You are broadcasting, but through the filter of what is in effect an informal or formal editorial presence.

Blogs may in reality be a mix of these attitudes, although not necessarily within the same entries. For example, my blog contains informally narrowcasted entries about the philosophy of Gilles Deleuze, as well as broadcasted entries about my baby. Some blogs are particularly effective at leading a general audience into an interest in very specialized topics, or vice versa. But quite often a blogger will make an assumption, usually a received and unconsidered assumption, about their audience, the audience appropriate for a blog, and stick to it. And from where is this assumption receieved? I suggest two key sources, each transmitting a different and contradictory assumption, and resulting in very different kinds of blog:

- The traditional broadcast medium (newspapers, radio, television) who present blogs in terms understandable and significant to themselves. Looking at the coverage of blogs in these media, one would assume that blogging is a broadcast medium, aiming to reach an unspecialized and general audience (in fact the blogs that they like are the ones that are capable of being translated into the traditional broadcast media);

- The network effect of friends who blog enticing their friends to also blog. In this case the tendency would be to blog for your friends, in response to your friends, and therefore to narrowcast.

Which of these two influences is the most prevalent? Examing the list of recent entries in Warwick Blogs usually indicates that the former may be more potent. Indeed it would appear that most bloggers are trying to be one-person-broadcast-media, with the majority of entries about topics of very general interest and requiring no specialist knowledge. There could be narrowcasted topics that we can’t see dues to privacy controls, but in fact I know that this is quite rare. We could also assume that the authors of these broadcasted entries are expecting a set of known readers to appreciate them, whilst still writing in an essentially broadcast style. I suspect that this says something about the kinds of social relations that exist between these bloggers. They are after all mostly students and hence only together for a very short and uncertain period of time, perhaps not long enough to develop deeper and more specialised shared interests.

We may also ask the question of the blog system itself: is it biased towards narrowcasting or broadcasting? Have a look at the Warwick Blogs homepage and see what you think. More importantly, what does a set of blogs (and their aggregation) implicitly say about the purpose of blogging? My guess is that a brief look at Warwick Blogs would give you the impression that bloggers write more for an unspecialized and general audience. The highly discursive nature of blogging (especially at Warwick) encourages this. The listing of topics that have received many comments reinforces this. The assumption is then that blog entries are written to prompt discussion amongst a general audience.

Understanding the academic desire to blog (or not)

Now consider the nature of "being an academic". What is the most significant feature? I would say specialization. In fact I would argue that universities exist as places in which quite extreme specialization can take place. This is so extreme that even two people in the same department may not have much of an understanding of each other's work (modal logic is a mystery to me). To an outsider that may seem bad. But it is in fact the very reason for giving people the time and space required to explore and innovate. Furthermore, I conjecture that most academics would respond to finding any spare time in their busy diaries by doing activities to work further on their specialization. If you're not an academic, and you don't believe me, think back to what it was like being an undergraduate. Did you get the sense that each individual academic was trying to pull you into their own particular specialized field? This is even more so for graduate students, as lecturers seek to recruit doctoral students (or at least sell their own books).

Asking again the question: "why should an academic blog?" – So far we have no answer.

Of course academics cannot stay in their silos of specialization permanently. They occassionaly have to crawl out of the cave and communicate their work to a slightly more broad audience. Ideas do need to be tested. They also need to be funded. Could they do this in a blog? Yes. Would they? Probably not. Consider just how carefully managed this process of academic exposure usually is, and how much work is required to get it right. The peer reviewed journal is one of two mechanisms for communicating academic work in a managed way; a tighly controlled way. Conferences are a little more wild and risky, but even so are regulated with high expectations. I know of academics that could talk brilliantly about anything at any time, and yet they still cancel conference appearances because their papers are not perfect.

From this perspective, the project of academic blogging looks doomed. Perhaps that is why very few academics turn up to my workshops on blogging? (In comparison to sessions on tools that help with their own private research).

Academic blogging 2

I seem to have done a fairly good job of demolishing the idea that blogs can be useful to academics. And yet I still stand by my statement that:

weblog technology (along with other new web tools) has the potential to dramatically enhance the “academic environment”, if applied intelligently.

The weblog is, after all, a powerful tool for recording and archiving the development of ideas, for exploiting that archive, for selectively exposing it to others, and for developing an identity and a presence. All of these activities are vital to the academic process. The key to using the technology is in understanding how it can be used to address a controlled audience (from an audience of one, the author, to the whole world). This is a matter of using the features built into the software, as well as exploiting writing techniques that more clearly define the audience and hence manage engagement with it. For example, one keep a blog containing entries about a specialised topic, sometimes stating that an entry is “just a conjecture” and other times stating that it is “more conclusive”. You can alert colleagues to entries that they will be interested in, asking for a response, even a formal peer review. But you can also expose these entries to the world, allowing for chance encounters with other academics, in the same or a related field. You may also find that over time words that you use, ideas that you develop, in your blog become more widely accepted. It could even attract funding.

However, for this to become common practice, changes must occur:

- We need to change people’s perception of the purpose of blogging, from a broadcast medium to a medium that is sophisticated enough to combine broad and narrowcasting as required;

- There needs to be more widespread adoption of the techniques for managing audiences and writing;

- The advantages of blogging for academics in specific situations need to be explicated and communicated, with real examples.

I shall explore this in another forthcoming entry.

Your comments on any aspect of this entry are most welcome.

April 05, 2006

E–learning Research: Factors for choosing e–learning projects

Follow-up to E–learning Research: Achieving success in e–learning development from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

I am therefore seeking:

- guidelines on selecting projects, such that those chosen are more significant and continually successful;

- means for encouraging the formation and completion of projects (by staff and students) that meet those criteria.

My first conjecture is that a successful e–learning development project requires at least the cooperative endeavours of IT providers (including development and support), the University (that is, services and interests that are global to the whole institution), and the end users (the staff and students who will be affected by the development, and who play a central role in making it happen, usually as part of the project team).

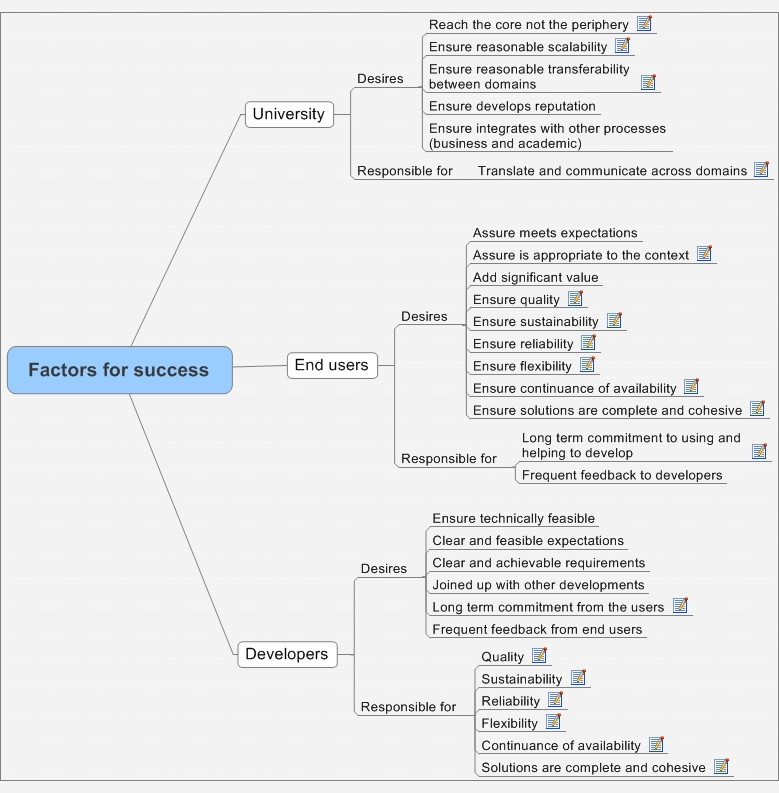

Each of these parties has a set of desires that make the development feasible and worthwhile. In return they have certain responsibilities that must be met for their own desires or those of others are to be met (and hence for the development to be successful). These desires and responsibilities form the factors that contribute to the success of a development. I am trying to create a comprehensive account of these factors. Here is the concept map node so far:

It should be immediately apparent that for all of this to be assured (rather than merely accidental), there needs to be a cooperation of the efforts and interests of the many people involved. At this point we should note that some people do believe that we simply should not worry about this problem. Coordination of all of these people and factors at the same time being too difficult. Rather, we should just stand back and allow new practices to emerge from a diverse network of people all innovating with the available toolset, and actively feeding new requirements to the IT providers and the University. The idea is that the near–viral force of "network effect" will result in positive change over time. This may indeed sometimes be true, and certainly is when countenanced on a very large scale (e.g. the whole internet). But within a University there just are not enough users with enough time and desire to innovate. Furthermore, demands on the time of core users (those who can assure that a new approach is permanently adopted) are so great as to prevent deeper innovation, affecting and improving core activities. Consequently innovation and innovators tend to be peripheral, thus failing on desire 1.1.1.1. Note that although there may be small and quite visible innovations, transferable across domains (1.1.1.3), they are not significant innovations and do not add significant value (1.2.1.3). I conclude then that deeper more widespread cooperation is essential for significant and cost–effective development (the Learning Grid was planned, many cooperated on it, it did not emerge out of the chaos).

(Note on strategy for Rob Johnson: a successful guerrilla operation is only achievable through the deployment of large numbers of operatives, each with plenty of time and committment. That is what distinguishes guerrilla war from terrorism).

Consistent and ongoing commitments are absolutely necessary, as is good communication. The big question concerns how to assure that this happens (problem 2 stated above). The common solution is to form projects that have their own strong distinct identity, and which unite the various partners. How can I do this?

My single greatest problem is in getting sufficiently consistent committment from end users, including staff and students, especially those who are core project members. If success is to be achieved through effective projects, then I must find a way of forming good projects that meet the list of factors for success. I shall now work on this question.

March 30, 2006

E–learning Progress Report: looking for a new job

Follow-up to E–learning Research: Achieving success in e–learning development from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

What are we trying to achieve?

I define the goal quite simply: the adoption of good new technologies by lecturers and students to enhance the teaching and learning process (which at Warwick includes research activities). The effort in adopting the new technologies should be justified by the value that they add, and not negated by any disruption that they introduce to existing practices. The end result should be to contribute to Warwick becoming a world class university.

How can I contribute to this?

Perhaps the best place to start is by asking: what am I good at? That is answerable by identifying what, out of the (far too many) things that I do, people value the most.

Rob Johnson identified something important today during a discussion of a planned skills and PDP development project in History. In response to his description of the project, I raised a few critical questions that need to be answered in considering and planning the project. Without first answering these questions, the project could be undermined. People often tell me that they value this input.

Secondly, I was able to demonstrate how the nature of the project and its deliverables might change in response to these answers. Most importantly I could suggest techniques (pedagogical and otherwise) and technologies that might address the identified problems. These suggestions were based on a mix of experience (they had been used elsewhere) and rational conjecture (they were new ideas that sound feasible).

So to summarise, what I am recognised as doing well:

- help people to think and plan critically;

- suggest possible solutions.

Note that there are other things that I could potentially do well, but for various reasons beyond my control, I cannot reliably contribute them to e-learning development.

What can I not contribute?

These positive contributions are good and valued. They create specific requirements, including:

- helping people to answer the critical questions (through deeper investigations);

- the absolutely fundamental requirement to provide a cohesive and complete set of tools and technologies that can be used to meet the requirements to an acceptable extent;

- the need to provide good and relavant examples illustrating possible solutions (academics are constantly asking for good relevant examples from real teaching).

Unfortunately, I am finding that I cannot satisfy all of these requirements at the same time, and am not getting sufficient help in doing so. Specifically, I find that:

- I do not have enough time and resource to help them to answer the critical questions through deeper invesitgations;

- I cannot provide, or source from elsewhere within the University, the required technologies and support infrastructure – we simply do not have provisions to meet the needs that I am constantly encountering;

- given that I am having to take personal responsibility for so many of the required e-learning activities, I do not have time available to generate and document the required body of examples – the fact that there are so many gaps in the technology and support provision, also makes this difficult.

Possible solutions?

I am finding that genuine success in e-learning development, or even moderately worthwhile progress, is not happening. These problems cannot be solved by an individual in isolation. They require team work, coordination, and strategy. Without team work and strategy, I am ending up having to fulfill almost every role in the e-learning development process myself (such a diversity as to include building web applications, teaching undergraduates, consulting with academics, project management, writing showcases, testing out new technologies and much more). I conclude that a new way of working is required.

March 28, 2006

E–learning Research: Achieving success in e–learning development

Key notes

Factors for success

Target the core not the periphery: End users can be described on a continuum between core and peripheral. Core users are closer to the main or most common business of the organisation, either in their own practice or in their power and influence over others. Why this matters: influential people make key decisions. Even core users with less direct power can operate a "network effect" – the use of a technique by one of these users makes it more likely that other users will also adopt it.

Assure is appropriate for the context: What is meant by context? This is the wider environment and community of learning, teaching and research. The project should emerge from and be defined by this context. The context includes:

- Current and future user expectations (staff and students).

- The aims and objectives of all of the users.

- Current and future practices and tactics of the users.

Context is influenced and summarised at a range of levels and perspectives including:

- Inter-university

- Pan-university

- Module team

- Research group

- Peer group

- Programme team

- Department

Seek necessary completeness and cohesion: Completeness is the provision of a well integrated and extensive range of tools and services, without gaps, along with all of the activities required to make them appropriate to the context and used widely and effectively.

Why this matters: end users should not embark on the use of a technology or a technique only to find that an essential component is missing. This is especially important when users are tentatively adapting to new approaches. Completeness is also an issue for the providers of services that should mesh closely with other services.

Some users are happy with speculative projects that may encounter incompleteness. Some activities can be carried out speculatively without guaranteed completeness. Other activities, such as exams, require guaranteed completeness of all required tools and techniques.

Activities required for success

Many activities (service provision, development, communication, training, support, review, evaluation, decision making etc) contribute to the achievement of successful e-learning development, realising the factors for success given above. These activities are widely varied, and require a skillset usually beyond a single person or small team. E-learning initiatives frequently fail becuase they attempt to undertake all of these activities with too limited a human resource. However, for the sake of completeness and consistency, these activities must be undertaken through tightly enmeshed and coordinated teamwork. Expanding some subnodes of these activities reveals the extent of the complexity:

Possible strategies for achieving success

The activities necessary for success in e-learning are great in depth and breadth of diversity. Mastery of the complete set by individuals is niether likely nor to be desired. Strategies have evolved to enable success without such complete control of the factors that contribute to its likelihood. These strategies tend to involve carving out a subset of the required activities, gaining mastery over that subset, and using various tactics to wield some kind of influence or power over the provision of the remaining activities. The problem may be sliced in two ways:

A) Project development, in which a goal is identified that makes use of a set of the available provisions, shapes the development of those provisions, and provides justification and validation of the available feature sets (or alternatively demonstrated gaps and limitations). This node opened out:

B) Service specialism, in which focus is placed upon the provision of a definite set of tools and features, with incremental development in return for limited application within the scope of those features. Node opened out:

A third technique may be called Information Exchange. This represents a retreat from any attempt to ensure completeness and consistency. It is withdrawl from close involvement with either project or service development. The user is in effect left to do much of the work of innovation, application of technologies, discovery of techniques, and identification of gaps and requirements. It is a safe strategy in the short term, but on a longer scale may lead nowhere. More about this node:

February 20, 2006

E–learning Report: Setting clear expectations – response to the Learning and Teaching Strategy

Writing about web page http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/insite/forum/learningteaching2009/feedback/

Excellence in creativity, innovation and diversity implies a mastery of change management. I argue that in order to achieve many of the aims and objectives laid out in the proposals, there must first be a commitment to understanding and effectively managing change throughout the university. Most importantly, an essential precursor to effective change is the clear and consistent setting and communication of expectations.

Why is change management of such importance? As a member of the E-learning Advisor Team, charged with the task of encouraging innovation and experimentation in learning and teaching, I frequently encounter a fundamental blocker to the success of such developments. No matter how highly we regard dynamism and creativity as an end towards which learning should strive, there seems to be a fundamental conservatism amongst those who are required to sign up to new developments. It could be argued that the introduction of top-up fees will drive our students to become even more conservative. They have definite expectations of a degree from Warwick and what contributes to its attainment. When faced with the introduction of a new requirement or activity (such as using a technology), their expectations are affronted. The response to change is often negative. Diversification of the nature of degrees, with for example the introduction of closer ties to career development, may further prompt such a response.

The Learning and Teaching Strategy proposals call for, as an aim, the recruitment of students with greater potential. I assume this means the recruitment of students who are dynamic and flexible, capable of working in an innovative and creative environment. This is a worthy aim, but we should not assume that it translates into students who can happily accept change and innovation at any point of their studies. They will have expectations of the nature of a degree and their commitment towards it. Creativity and innovation may well have a place within those expectations. That place should be significant. However, there is always a tension between change and the demand for firmly held reasonable expectations to be met.

As a solution to this which enables acceptable change whilst promoting creativity and innovation, the clear and consistent setting of expectations must be the highest priority. A module or programme that employs a specific teaching technique should be clearly signposted as such. Where students are expected to contribute to the development of a new technique, and that contribution is seen as a useful means for developing their own creative skills, they should be told so. We could state that these are expectations at a global university level, or for individual modules. The key is to set clear expectations and to stick to them.

Furthermore, business theorists might argue that in an increasingly competitive market, a quality leader such as Warwick must respond to commodification by helping the market to attain a more sophisticated understanding of its products. The aim of setting expectations more clearly is a vital requirement underpinning this sophistication. This is even more so for an institution that offers creativity, innovation and diversity as its selling point.

My conclusion then is that we could add as a further aim: an institutional focus upon setting clear and understandable expectations throughout (from recruitment onwards, and most importantly through induction), communicating these expectations, and enforcing our commitment to them.

December 14, 2005

Teaching Techniques: confidence based assessment as a solution to prediction failure

Writing about an entry you don't have permission to view

There's an important point in this for university teaching, especially in subjects in which accurate prediction is paramount. Students must learn to assess the certainty of their own judgements. As Chris May points out, the problem is that "experts aren't very good at communicating the uncertainty of their predictions" – which probably means that they aren't very good at objectifying the degree of certainty to themselves.

I recently saw a technique demonstrated that helps with this. It is called "confidence based assessment", and is used in some medical schools. The student is given a series of questions. Obviously they must try to get the right answer, but more importantly they are asked to assess the confidence with which they give each answer. The answer/confidence combination works along these lines

- If a student gives the wrong answer confidently, that recieves the worst possible grade;

- If they give the wrong answer but are not confident, then they get a better grade;

- Giving the right answer but without confidence is OK, but not ideal, as in reality it could end up with them waisting time having to consult others;

- The best answer is that which is correct and made with confidence.

The outcome of this should be that the student knows when to consult others (or text books etc), they know when not to act independently. They also know when they can make a quick and precise decision, thus acting correctly and efficiently.

This is all very well, but exactly how do you equip someone with the skills to be confident when justified or doubtful when necessary? This is of course the predominant interest of a branch of philosophy called epistemology (or philosophy of science in a more restricted form).

Conclusion (not entirely justified): medical students must do philosophy.

November 24, 2005

Research Techniques: making historical timelines

The requirements are:

- plot lots of historical events visually on a line;

- allow different types of event to be categorised, for example, publishing events, political events;

- allow for some interactivity, with the user being able to show or hide categories of events;

- allow events to be linked to other web pages containing more detail;

- allow icons on events;

- can be embedded in a web page.

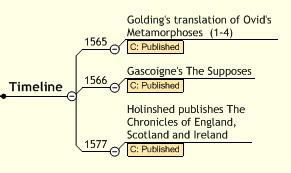

One solution would be to create a Flash application for this. We might persue that for current timelines (as in ones of current events), as we can get the data from a Newsbuilder calendar. But for historical events, I tried something else – using MindManager. Here's the result of plotting some events from the 16th century:

This could meet all of the above requirements, including icons, links and categorisation. It also allows for filtering of events, for example if I apply a filter that only shows publishing events:

Adding the timeline to a web page is not quite as straightforward as it should be. But the creation and editing of the timelines is made very easy.

November 22, 2005

Research Techniques: Mapping a blog with RSS and MindManager

MindManager is the leading concept mapping tool. I have recently described it as the best piece of academic software I have ever used. In fact it is so good that we (as in the elab E-learning Advisor Team) are buying a site licence, and will soon make it available to everyone. I'll explain more in another entry soon. For now, here's a note on one particularly impressive feature.

As part of the process of creating a map of my research, I am trying to extract some order out of the 85 entries that I have written in my blog as part of my research process, all of which are tagged as philosophy_research . My starting point has been to list all of the books that I have read (or am currently reading), and which have contributed to those entries.

My next step is, for each of those books, to create a list of concepts, questions and issues covered. Fortunately, I have tagged my blog entries so that it is easy for me to get a list of entries relevant to each author. For example, there is a Deleuze list of entries. By looking at the titles of the entries in these lists, I can extract a list of key concepts. In some cases the title itself is insufficient, so I have to go and read the entries themselves.

MindManager has a really useful feature that can help with this: News Feed import. This can read an RSS description of a set of news entries in a news feed. A blog can be treated as such a news feed, and in fact Warwick Blogs provides such RSS descriptions. For example, see the url http://blogs.warwick.ac.uk/rbotoole?rss=rss_2_0 which gives an RSS description of my latest blog entries. More usefully, you can get an RSS description of a page listing all of your entries that are tagged with a specified keyword. For example, http://blogs.warwick.ac.uk/rbotoole/tag/guattari/?rss=rss_2_0&num=100&start=0 lists the latest 100 entries, starting with the most recent (0), that are tagged with the keyword "Guattari".

When one of these RSS feeds is imported into a MindManager map, you get an auto-generated list of the selected blog entry titles. For example:

From this I can see what aspects of the work of each writer I have taken an interest in.

This is just one of the features of MindManager that I use for my research, e-learning and personal life. Once we have the site licence in place and the software accessible to people, I will be running some seminars and workshops on it, similar to the popular introduction to concept mapping session that I recently ran for the IT Services Training Programme.

If you are interested in this, then please contact me and I will add you to my mailing list.

November 11, 2005

Research Notes: switching between cognitive and behavioural/affective attention

Writing about web page http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/philosophy/research/akbep/

I have been reading What teachers know the final report of the project Attention and the knowledge bases of expertise (Michael Luntley and Janet Ainley). So far it has proved to be quite thought provoking, both in terms of philosophy and also in direct pedagogical implications. The aim of the project (broadly) is to examine the conjecture that the expert knowledge of the teacher goes much further than what is commonly and easily represented in a lesson plan. In fact, as I think they demonstrate, the most significant expert knowledge involves the teachers understanding of patterns of attentional activity amongst the students and themselves.

Teaching is, as I recognize from my own experience, about engaging with and guiding the attentional activity of the students in discovery, skills practice and moving towards independence. My recent work with concept mapping techniques, in which a map is used to focus and guide attention towards insight and discovery, has given demonstration of this.

There is, however, one assumption in the methodology of the project that is philosophically controversial, thought provoking, and significant. That is the disctinction used between cognitive tasks and behavioural/affective tasks. The challenge to this comes from Andy Clark's extended cognition thesis. The nature of the challenge is a concerted effort by Clark to show that many practical activities, and the tools that they use, are in fact inseperable from and definitively part of cognitive activities. The relationship between mind and world is porous. The case of IT teaching would support this. The process of carrying out an algorithm on a computer, physically operating the interface, is a classic case of thinking through a non-brain-contained activity. It could also be said to have an affective component (this is more contentious).

The teaching observations and subsequent interviews carried out as part of the research noted one very significant, and to me familiar, case where the difference between the cognitive and the behavioural/affective has to be considered. Most teachers recognize this situation:

- a class is working on a physical ativity, requiring the playing out of a set of behaviours;

- the teacher wants the class to abstract out of that activity a concept (or model) that summarizes, extends, makes generic, or contextualises the activity;

- the teacher must somehow shift the attention of the students from the physical activity to conceptual thought.

You will often hear me signposting this in a lesson: "we now need to focus on the following concepts which you should think and use during the practical activity". That's fine when I'm teaching adults, but with children it is much more difficult.

This is interesting because it indicated that there are two different forms of activity, and teachers must understand the relationship between them. The challenge back to Clark is: does this experience mark out a separation of the physical and the cognitive? I would say that there is a clear difference between these two modes of learning, but it is not a physical/cognitive distinction. As evidence, consider the use of physical tools in the understanding of a concept or model – the classic example being a concept map shown by the teacher at the point of teaching the concept.

The really significant issue is: what are the differences that mark out the two modes of learning. From experience I would say that there is a difference. This difference, I argue, marks out the separation of behavioural and conceptual. I suspect that considering this distinction more fully would give a better understanding of attention, insight, learning etc. So then, what is a concept?

Note that I don't think that this in any way undermines the argument about attention. In fact it may add weight and subtlety to it. Teachers should certainly be aware of the grey areas between the physical and the mental, as that may be where most learning actually happens. A big question for every teacher is: how does a physical embedded activity become an independent concept?

If you are interested in this entry, then please contact me

Teaching Techniques: concept maps developing critical and investigative skills in presentations

Follow-up to Session Report: Introduction to concept mapping for PhD and staff from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

I just overheard a discussion that some undergraduates were having. They were planning a seminar presentation. The discussion seemed to consist of:

- guessing what topics the tutor would expect them to cover;

- analysing the available information (text books) to identify which of the topics they could cover;

- identifying facts for some of the topics that would justify their claims to coverage.

If this were the sole scope of the resulting presentation, they would certainly not justify a claim to honours degree level performance, or even undergraduate certificate performance (see the QQA descriptors for details of what that means). But I guess (hope) that this actually represents just the first stage of the process, in which the students assure themselves of some self-confidence in the subject domain by getting a sense that they have at least a minimal degree of coverage. However, I have observed many undergraduate seminars in which the students have come prepared only with a check-list of facts, and the tutor has subsequently had to drag investigative and critical thought out of them.

Note that my argument is not that this kind of activity is wrong for undergraduates, but rather that it only represents a small aspect of what they should be doing. And more significantly, it is the aspect of the process that they focus upon. My guess is that this is the case because it gives them confidence in preparation for the presentation. A check-list of topics and facts is simply more tangible and less subject to challenge than "a critical and investigative processes".

This is where I think technology can make a significant contribution. If we could identify ways of making the critical and investigative process more concrete, more controlled for the student in the presentation, then we might be able to give them more confidence. Of course they may still lack confidence in the arguments that they produce, but we should expect that a more concrete representation of the arguments (in relation to the underlying knowledge base) has the benefit of making it easy to rehearse the investigative and critical discourse.

And that is exactly what is offered by some of the concept mapping techniques that I described.

A concept map is a simple and efficient way of recording facts and ideas. Each node in a map refers to a fact or idea, which may be documented elsewhere (to which the node can be linked), or which may exist in the memory of the map author[s]. Nodes are linked and arranged in some kind of order. This order may represent an assumed order of things in the world, or it may represent the order in which they can be investigated and understood (philosophically these amount to the same thing). Thus in creating and using a concept map, critical and investigative issues are automatically raised. Of course it is still possible to naively build a map as a simple check-list. However, in transferring from the map (non-sequential) to a presentation (sequential to a great extent), questions are raised:

- where do I start?

- does the audience need a high level overview?

- does the audience need to connect with their own detailed and specific perspective?

- what path do I follow?

- which nodes are most important?

- what are the possible links?

- where are the gaps?

- what detail is required?

- at what points should I consider making the path contingent?

- how will I modify the map as it is used?

The available technologies, such as the FreeMind and MindManager applications, have features that support and indeed encourage this behaviour. There are also well developed presentation and writing techniques that take advantage of these features to create presentations that are both investigative/critical and to a great extent predictable and confident.

I'm going to investigate this further, and am looking for opportunities to use these techniques with students.

Any volunteers? If so then contact me

Robert O'Toole

Robert O'Toole

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading