All 58 entries tagged E-Learning

View all 300 entries tagged E-Learning on Warwick Blogs | View entries tagged E-Learning at Technorati | View all 3 images tagged E-Learning

March 28, 2006

E–learning Research: Achieving success in e–learning development

Key notes

Factors for success

Target the core not the periphery: End users can be described on a continuum between core and peripheral. Core users are closer to the main or most common business of the organisation, either in their own practice or in their power and influence over others. Why this matters: influential people make key decisions. Even core users with less direct power can operate a "network effect" – the use of a technique by one of these users makes it more likely that other users will also adopt it.

Assure is appropriate for the context: What is meant by context? This is the wider environment and community of learning, teaching and research. The project should emerge from and be defined by this context. The context includes:

- Current and future user expectations (staff and students).

- The aims and objectives of all of the users.

- Current and future practices and tactics of the users.

Context is influenced and summarised at a range of levels and perspectives including:

- Inter-university

- Pan-university

- Module team

- Research group

- Peer group

- Programme team

- Department

Seek necessary completeness and cohesion: Completeness is the provision of a well integrated and extensive range of tools and services, without gaps, along with all of the activities required to make them appropriate to the context and used widely and effectively.

Why this matters: end users should not embark on the use of a technology or a technique only to find that an essential component is missing. This is especially important when users are tentatively adapting to new approaches. Completeness is also an issue for the providers of services that should mesh closely with other services.

Some users are happy with speculative projects that may encounter incompleteness. Some activities can be carried out speculatively without guaranteed completeness. Other activities, such as exams, require guaranteed completeness of all required tools and techniques.

Activities required for success

Many activities (service provision, development, communication, training, support, review, evaluation, decision making etc) contribute to the achievement of successful e-learning development, realising the factors for success given above. These activities are widely varied, and require a skillset usually beyond a single person or small team. E-learning initiatives frequently fail becuase they attempt to undertake all of these activities with too limited a human resource. However, for the sake of completeness and consistency, these activities must be undertaken through tightly enmeshed and coordinated teamwork. Expanding some subnodes of these activities reveals the extent of the complexity:

Possible strategies for achieving success

The activities necessary for success in e-learning are great in depth and breadth of diversity. Mastery of the complete set by individuals is niether likely nor to be desired. Strategies have evolved to enable success without such complete control of the factors that contribute to its likelihood. These strategies tend to involve carving out a subset of the required activities, gaining mastery over that subset, and using various tactics to wield some kind of influence or power over the provision of the remaining activities. The problem may be sliced in two ways:

A) Project development, in which a goal is identified that makes use of a set of the available provisions, shapes the development of those provisions, and provides justification and validation of the available feature sets (or alternatively demonstrated gaps and limitations). This node opened out:

B) Service specialism, in which focus is placed upon the provision of a definite set of tools and features, with incremental development in return for limited application within the scope of those features. Node opened out:

A third technique may be called Information Exchange. This represents a retreat from any attempt to ensure completeness and consistency. It is withdrawl from close involvement with either project or service development. The user is in effect left to do much of the work of innovation, application of technologies, discovery of techniques, and identification of gaps and requirements. It is a safe strategy in the short term, but on a longer scale may lead nowhere. More about this node:

February 20, 2006

E–learning Report: Setting clear expectations – response to the Learning and Teaching Strategy

Writing about web page http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/insite/forum/learningteaching2009/feedback/

Excellence in creativity, innovation and diversity implies a mastery of change management. I argue that in order to achieve many of the aims and objectives laid out in the proposals, there must first be a commitment to understanding and effectively managing change throughout the university. Most importantly, an essential precursor to effective change is the clear and consistent setting and communication of expectations.

Why is change management of such importance? As a member of the E-learning Advisor Team, charged with the task of encouraging innovation and experimentation in learning and teaching, I frequently encounter a fundamental blocker to the success of such developments. No matter how highly we regard dynamism and creativity as an end towards which learning should strive, there seems to be a fundamental conservatism amongst those who are required to sign up to new developments. It could be argued that the introduction of top-up fees will drive our students to become even more conservative. They have definite expectations of a degree from Warwick and what contributes to its attainment. When faced with the introduction of a new requirement or activity (such as using a technology), their expectations are affronted. The response to change is often negative. Diversification of the nature of degrees, with for example the introduction of closer ties to career development, may further prompt such a response.

The Learning and Teaching Strategy proposals call for, as an aim, the recruitment of students with greater potential. I assume this means the recruitment of students who are dynamic and flexible, capable of working in an innovative and creative environment. This is a worthy aim, but we should not assume that it translates into students who can happily accept change and innovation at any point of their studies. They will have expectations of the nature of a degree and their commitment towards it. Creativity and innovation may well have a place within those expectations. That place should be significant. However, there is always a tension between change and the demand for firmly held reasonable expectations to be met.

As a solution to this which enables acceptable change whilst promoting creativity and innovation, the clear and consistent setting of expectations must be the highest priority. A module or programme that employs a specific teaching technique should be clearly signposted as such. Where students are expected to contribute to the development of a new technique, and that contribution is seen as a useful means for developing their own creative skills, they should be told so. We could state that these are expectations at a global university level, or for individual modules. The key is to set clear expectations and to stick to them.

Furthermore, business theorists might argue that in an increasingly competitive market, a quality leader such as Warwick must respond to commodification by helping the market to attain a more sophisticated understanding of its products. The aim of setting expectations more clearly is a vital requirement underpinning this sophistication. This is even more so for an institution that offers creativity, innovation and diversity as its selling point.

My conclusion then is that we could add as a further aim: an institutional focus upon setting clear and understandable expectations throughout (from recruitment onwards, and most importantly through induction), communicating these expectations, and enforcing our commitment to them.

December 14, 2005

Teaching Techniques: confidence based assessment as a solution to prediction failure

Writing about an entry you don't have permission to view

There's an important point in this for university teaching, especially in subjects in which accurate prediction is paramount. Students must learn to assess the certainty of their own judgements. As Chris May points out, the problem is that "experts aren't very good at communicating the uncertainty of their predictions" – which probably means that they aren't very good at objectifying the degree of certainty to themselves.

I recently saw a technique demonstrated that helps with this. It is called "confidence based assessment", and is used in some medical schools. The student is given a series of questions. Obviously they must try to get the right answer, but more importantly they are asked to assess the confidence with which they give each answer. The answer/confidence combination works along these lines

- If a student gives the wrong answer confidently, that recieves the worst possible grade;

- If they give the wrong answer but are not confident, then they get a better grade;

- Giving the right answer but without confidence is OK, but not ideal, as in reality it could end up with them waisting time having to consult others;

- The best answer is that which is correct and made with confidence.

The outcome of this should be that the student knows when to consult others (or text books etc), they know when not to act independently. They also know when they can make a quick and precise decision, thus acting correctly and efficiently.

This is all very well, but exactly how do you equip someone with the skills to be confident when justified or doubtful when necessary? This is of course the predominant interest of a branch of philosophy called epistemology (or philosophy of science in a more restricted form).

Conclusion (not entirely justified): medical students must do philosophy.

November 24, 2005

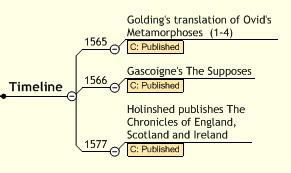

Research Techniques: making historical timelines

The requirements are:

- plot lots of historical events visually on a line;

- allow different types of event to be categorised, for example, publishing events, political events;

- allow for some interactivity, with the user being able to show or hide categories of events;

- allow events to be linked to other web pages containing more detail;

- allow icons on events;

- can be embedded in a web page.

One solution would be to create a Flash application for this. We might persue that for current timelines (as in ones of current events), as we can get the data from a Newsbuilder calendar. But for historical events, I tried something else – using MindManager. Here's the result of plotting some events from the 16th century:

This could meet all of the above requirements, including icons, links and categorisation. It also allows for filtering of events, for example if I apply a filter that only shows publishing events:

Adding the timeline to a web page is not quite as straightforward as it should be. But the creation and editing of the timelines is made very easy.

November 22, 2005

Research Techniques: Mapping a blog with RSS and MindManager

MindManager is the leading concept mapping tool. I have recently described it as the best piece of academic software I have ever used. In fact it is so good that we (as in the elab E-learning Advisor Team) are buying a site licence, and will soon make it available to everyone. I'll explain more in another entry soon. For now, here's a note on one particularly impressive feature.

As part of the process of creating a map of my research, I am trying to extract some order out of the 85 entries that I have written in my blog as part of my research process, all of which are tagged as philosophy_research . My starting point has been to list all of the books that I have read (or am currently reading), and which have contributed to those entries.

My next step is, for each of those books, to create a list of concepts, questions and issues covered. Fortunately, I have tagged my blog entries so that it is easy for me to get a list of entries relevant to each author. For example, there is a Deleuze list of entries. By looking at the titles of the entries in these lists, I can extract a list of key concepts. In some cases the title itself is insufficient, so I have to go and read the entries themselves.

MindManager has a really useful feature that can help with this: News Feed import. This can read an RSS description of a set of news entries in a news feed. A blog can be treated as such a news feed, and in fact Warwick Blogs provides such RSS descriptions. For example, see the url http://blogs.warwick.ac.uk/rbotoole?rss=rss_2_0 which gives an RSS description of my latest blog entries. More usefully, you can get an RSS description of a page listing all of your entries that are tagged with a specified keyword. For example, http://blogs.warwick.ac.uk/rbotoole/tag/guattari/?rss=rss_2_0&num=100&start=0 lists the latest 100 entries, starting with the most recent (0), that are tagged with the keyword "Guattari".

When one of these RSS feeds is imported into a MindManager map, you get an auto-generated list of the selected blog entry titles. For example:

From this I can see what aspects of the work of each writer I have taken an interest in.

This is just one of the features of MindManager that I use for my research, e-learning and personal life. Once we have the site licence in place and the software accessible to people, I will be running some seminars and workshops on it, similar to the popular introduction to concept mapping session that I recently ran for the IT Services Training Programme.

If you are interested in this, then please contact me and I will add you to my mailing list.

November 11, 2005

Research Notes: switching between cognitive and behavioural/affective attention

Writing about web page http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/philosophy/research/akbep/

I have been reading What teachers know the final report of the project Attention and the knowledge bases of expertise (Michael Luntley and Janet Ainley). So far it has proved to be quite thought provoking, both in terms of philosophy and also in direct pedagogical implications. The aim of the project (broadly) is to examine the conjecture that the expert knowledge of the teacher goes much further than what is commonly and easily represented in a lesson plan. In fact, as I think they demonstrate, the most significant expert knowledge involves the teachers understanding of patterns of attentional activity amongst the students and themselves.

Teaching is, as I recognize from my own experience, about engaging with and guiding the attentional activity of the students in discovery, skills practice and moving towards independence. My recent work with concept mapping techniques, in which a map is used to focus and guide attention towards insight and discovery, has given demonstration of this.

There is, however, one assumption in the methodology of the project that is philosophically controversial, thought provoking, and significant. That is the disctinction used between cognitive tasks and behavioural/affective tasks. The challenge to this comes from Andy Clark's extended cognition thesis. The nature of the challenge is a concerted effort by Clark to show that many practical activities, and the tools that they use, are in fact inseperable from and definitively part of cognitive activities. The relationship between mind and world is porous. The case of IT teaching would support this. The process of carrying out an algorithm on a computer, physically operating the interface, is a classic case of thinking through a non-brain-contained activity. It could also be said to have an affective component (this is more contentious).

The teaching observations and subsequent interviews carried out as part of the research noted one very significant, and to me familiar, case where the difference between the cognitive and the behavioural/affective has to be considered. Most teachers recognize this situation:

- a class is working on a physical ativity, requiring the playing out of a set of behaviours;

- the teacher wants the class to abstract out of that activity a concept (or model) that summarizes, extends, makes generic, or contextualises the activity;

- the teacher must somehow shift the attention of the students from the physical activity to conceptual thought.

You will often hear me signposting this in a lesson: "we now need to focus on the following concepts which you should think and use during the practical activity". That's fine when I'm teaching adults, but with children it is much more difficult.

This is interesting because it indicated that there are two different forms of activity, and teachers must understand the relationship between them. The challenge back to Clark is: does this experience mark out a separation of the physical and the cognitive? I would say that there is a clear difference between these two modes of learning, but it is not a physical/cognitive distinction. As evidence, consider the use of physical tools in the understanding of a concept or model – the classic example being a concept map shown by the teacher at the point of teaching the concept.

The really significant issue is: what are the differences that mark out the two modes of learning. From experience I would say that there is a difference. This difference, I argue, marks out the separation of behavioural and conceptual. I suspect that considering this distinction more fully would give a better understanding of attention, insight, learning etc. So then, what is a concept?

Note that I don't think that this in any way undermines the argument about attention. In fact it may add weight and subtlety to it. Teachers should certainly be aware of the grey areas between the physical and the mental, as that may be where most learning actually happens. A big question for every teacher is: how does a physical embedded activity become an independent concept?

If you are interested in this entry, then please contact me

Teaching Techniques: concept maps developing critical and investigative skills in presentations

Follow-up to Session Report: Introduction to concept mapping for PhD and staff from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

I just overheard a discussion that some undergraduates were having. They were planning a seminar presentation. The discussion seemed to consist of:

- guessing what topics the tutor would expect them to cover;

- analysing the available information (text books) to identify which of the topics they could cover;

- identifying facts for some of the topics that would justify their claims to coverage.

If this were the sole scope of the resulting presentation, they would certainly not justify a claim to honours degree level performance, or even undergraduate certificate performance (see the QQA descriptors for details of what that means). But I guess (hope) that this actually represents just the first stage of the process, in which the students assure themselves of some self-confidence in the subject domain by getting a sense that they have at least a minimal degree of coverage. However, I have observed many undergraduate seminars in which the students have come prepared only with a check-list of facts, and the tutor has subsequently had to drag investigative and critical thought out of them.

Note that my argument is not that this kind of activity is wrong for undergraduates, but rather that it only represents a small aspect of what they should be doing. And more significantly, it is the aspect of the process that they focus upon. My guess is that this is the case because it gives them confidence in preparation for the presentation. A check-list of topics and facts is simply more tangible and less subject to challenge than "a critical and investigative processes".

This is where I think technology can make a significant contribution. If we could identify ways of making the critical and investigative process more concrete, more controlled for the student in the presentation, then we might be able to give them more confidence. Of course they may still lack confidence in the arguments that they produce, but we should expect that a more concrete representation of the arguments (in relation to the underlying knowledge base) has the benefit of making it easy to rehearse the investigative and critical discourse.

And that is exactly what is offered by some of the concept mapping techniques that I described.

A concept map is a simple and efficient way of recording facts and ideas. Each node in a map refers to a fact or idea, which may be documented elsewhere (to which the node can be linked), or which may exist in the memory of the map author[s]. Nodes are linked and arranged in some kind of order. This order may represent an assumed order of things in the world, or it may represent the order in which they can be investigated and understood (philosophically these amount to the same thing). Thus in creating and using a concept map, critical and investigative issues are automatically raised. Of course it is still possible to naively build a map as a simple check-list. However, in transferring from the map (non-sequential) to a presentation (sequential to a great extent), questions are raised:

- where do I start?

- does the audience need a high level overview?

- does the audience need to connect with their own detailed and specific perspective?

- what path do I follow?

- which nodes are most important?

- what are the possible links?

- where are the gaps?

- what detail is required?

- at what points should I consider making the path contingent?

- how will I modify the map as it is used?

The available technologies, such as the FreeMind and MindManager applications, have features that support and indeed encourage this behaviour. There are also well developed presentation and writing techniques that take advantage of these features to create presentations that are both investigative/critical and to a great extent predictable and confident.

I'm going to investigate this further, and am looking for opportunities to use these techniques with students.

Any volunteers? If so then contact me

November 04, 2005

Session Report: Introduction to concept mapping for PhD and staff

Writing about web page http://freemind.sourceforge.net

Rather than a text based hand-out and lesson plan, I now always just use a concept map. This is given to the students in both an electronic format and on paper. The paper based handout contains several pages, each with a different set of nodes visible or hidden (following the planned path through the map). I start with a top level view, with all of the detail hidden. At this point I can check with the audience to see if the session matches their expectations, and if there are any sections they would like me to focus on. This approach is repeated as I drill down into detail through the rest of the session. Here's the top level for the concept mapping session:

Instead of immediately pliunging into the detail of node 1, we did a little exercise. Firstly, I introduced myself using a concept map that details interesting information about me (requires FreeMind to view) my work and my research. I made this available to the students, so that they could practice navigating and extending (adding to and annotating) a map. I then gave them an amusing scenario to play out in pairs, that would require them to create and use (in a discussion) a similar map about themselves.

This exercise illustrated some of the ways in which concept maps can be useful in planning, recording, and presenting to an unfamiliar audience. The students seemed to really enjoy it, and in fact several of them continued working on their maps after the session ended. Following up on the lessons learned from the exercise, we looked in detail at the second node of the presentation map "Why Concept Map" (after checking with the class, I skipped over the first node, which seemed un-necessary).

The first node is shown below:

And the second:

Out of these ideas for how to use maps, the nodes on "pattern discovery", "direct communication of ideas" and "frameworking writing" were of particular interest. I demonstrated a quite sophisticated map that I use for my philosophy research. I therefore focussed on these in the next two sections of the session, starting with node 3, "elements of a concept map", which covered the different types of element that must or can be used:

Next we moved onto the most important part of the session, node 4 "how to read or present a map". The first of the suggested techniques, "drilling down" was already obvious, as I had been using it throughout the session. This involves starting at the centre of the map, at the general level, and then moving down through increasing levels of detail as required (I check with the students to see if they need more detail). This is particularly good if you are presenting or writing to an audience that is unfamilar.

The second technique is "expanding out", which involves starting with a specific detail familiar to the audience, and then moving upwards to give that detail context, and across to connect it to other nodes. This is good if you have a specialised audience or audiences, and you want to show them the bigger picture.

These techniques are very powerful as means for frameworking presentations and writing. In particular, I recomended that when trying to create a document from a map, one should work out a path through the map (drilling down or expanding out), and rehearse it with someone. Make a commentary (written or recorded) as you go along.

Unfortunately we were now running out of time, so the coverage of the technical topics was limited. However, my message is fairly straightforwards:

- don't overlook pen and paper, or the use of whiteboards;

- MindJet MindManager is the best software for serious research work, with its fast intuitive approach and interoperability with Office;

- MindManager has limtations (no Mac or Linux version, too much functionality, and its expensive);

- the free alternative (almost a clone) is FreeMind which is open source, java based, has Mac and Linux versions, as well as a web applet, is interoperable with MindManager, and is entirely free and easy to download and install.

In fact, my recomendation was to use FreeMind until you really need some of the sophisticated functionality of MindManager. We used FreeMind during the session, and it was great. The ease with which nodes can be inserted and extended, using enter and insert, makes it the perfect tool for supporting fast thinking and planning. It's abilities with icons are a little limited. Moving nodes around isn't as slick as MindManager. But this not necessarily a blocker. Printing is also quite poor, but with a little investigation, I think I will be able to work it out.

If you like the sound of this session, then contact me a I am considering repeating it.

UPDATE: we now have a site licence for the very slick MindManager software. This is available to all staff and students.

November 01, 2005

Planning Notes: All 95 philosophy research entries keyword tagged

A few of the advantages of tags are:

- you can easily invent new tags for each new entry;

- you can re-use tags previously used in your own blog, or even in other people's blogs;

- for each tag, you have an auto-generated page showing all of the entries containing the tag, for example, see the list for the tag deleuze

- the most frequently used tags in a blog are listed in the left hand column, linking to pages that show entries for each of the tags;

- a page can be accessed for any combination of tags, for example, deleuze and art

- you can get a list of entries that contain one or more tags within a department or the whole of Warwick Blogs, for example, this page shows entries on art

- a single entry can have more than one tag, thus allowing it to be categorised in more than one way

This is potentially powerful, especially as people are starting to consistently share tags in an organised way. Expect to see this approach used in teaching in the future, especially as Sitebuilder supports a similar keyword tagging system, and we are writing "thematic navigation" tools that exploit it.

As for my own blog, it may well be the most thoroughly tagged blog yet. For each of the 95 philosophy entries, I added tags that represent the concepts covered, as well as the philosophers and books referenced. So now it is possible for me to see a page that lists all of my entries that relate to the concept extended_cognition

or, you can see a page listing entries about the book germinal_life

My ultimate plan is to take the complete list of concepts used in my philosophy entries, add them to a concept map, organise them with connections, and link them back to the pages that list them in my blog.

If you are interested in this idea, then contact me

October 22, 2005

Research Notes: small world networks, extended cognition, the mangrove effect, blogs

Follow-up to Research Plan: ideas for researching networking, narrowcasting and broadcasting by bloggers from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

As I descibe in a previous entry , Clark uses the lifecyle of a mangrove island as a metaphor for how we sometimes use public language to speculatively play with ideas and see how they grow. I summarise metaphor as follows:

a mangrove seeds itself in shallow water, grows roots, traps other roots and particles, forms a network of roots with other mangroves that seed nearby (helped by the first mangrove), and eventually forms a more solid island within the sea.

Clark's argument is that by stating words publicly using an external cognitive apparatus (a web log would be a good example), even when they do not represent well formed ideas, thoughts and sense can be encouraged to form. We can easily play with the publicy stated words, manipulating them and seeing what emerges as they connect with other words. As a social process, involving other minds, this technique can lead in unexpected and successful directions.

It seems to me that "mangrove" style social thinking could be a core activity of the localized cliques that are probably the context for most blog entries. The clique tends to select phrases to be repeated locally, and provides opportunities for social thinking in a controlled space. But the small world network of Warwick Blogs offers two other possibilities:

- ideas that become well-formed can be transmitted to other localized networks through 'hubs' (people or pages that are authoritative in presenting selections of worthwhile content);

- ideas can also just free-float from one clique to another, for example via the "show all" page, where they may take root, or at least make the transmission through a hub more likely (hearing a message through several channels makes it more likely to be trusted and valued).

October 21, 2005

Research Plan: ideas for researching networking, narrowcasting and broadcasting by bloggers

Follow-up to Presentation of blogs at Oxford Brookes from Transversality - Robert O'Toole

During my recent presentation at Oxford Brookes about Warwick Blogs (during which there was an excellent debate), someone made the observation that from the perspective of some outside person browsing through the latest entries in the "showall" aggregation page, it would be hard to understand why anyone would read our blogs, and consequently (given that most people write with the expectation that someone else will read their entries), why would anyone therefore ever write anything?

This wasn't a crude condemnation of the standard of writing within Warwick Blogs. Rather, the observation was that it was hard for an outsider to understand what is interesting in most of the entries (although some are genuinely interesting to the outside world).

Having just read Mark Buchanan's book on small world networks, I could see the error in this observation.

The assumption behind this attitude is that the entries within Warwick Blogs are on the whole written so that any random person may come along and find them interesting and worthwhile. The question assumed that writing a blog is a form of "broadcasting". Indeed this is understandable, as it tends to be such "broadcast" style blogs, aimed at a general and unknown audience, that have caught the interest of the media. The reason for this bias may well be that the traditional media somehow sense that they are being challenged in their dominance of broadcasting.

I suspect that, on the contrary, many blog entries are written with relatively narrow audiences in mind (narrowcasting), but with the open possibility that a wider range of people may end up reading them. This is entirely consistent with the "small world network" model. Meaningful activity occurs on a local and limited scale, determined by the individuals in close proximity. In the case of blogs, that is likely to be other friends who blog, and probably in many cases the friends who introduced the author to blogging. That makes for lots of very small and localized activity, meaningful within isolated cliques.

But there's more to a small world network than that. Operating within a clique presents the risk of being disconnected from the outside world. One may lose track of how to connect to new and unknown people. For a student, that is potentially disasterous, as at some point reality will bite and the clique will dissolve (reaching the end of the course for example). So it makes sense for members of the clique to make some consideration of the outside, to open themselves up to possible extra-clique connections. The clique makes sense of the activity, but the outside is needed to give a small reality check, to add a little affirmation that the activity has value beyond the clique, and to safeguard that value should the clique suddenly dissolve. To cope with this, small world networks emerge, with "hub nodes" that provide a connection between the clique and the outside (or other cliques). These hubs take many forms. In some cases a single key individual may play the role. In other cases, a broadcasting channel may do the trick.

What is really interesting, and perhaps not yet thoroughly researched, is how different the arrangements of different types of clique and hub may be of great significance. For example, in designing a new interpersonal communication system that relies both on cliques and on hubs, if we get the type of hub wrong, then the development of the system may be restricted.

My question then is this: what is the arrangement of cliques and hubs in Warwick Blogs? What kind of small world network is it? Could it work better with a different arrangement of cliques and hubs? Fortunately, I think that it should be easy for us to get empirical data on this, so long as we ask the right questions. Our questions will be based on a model of the relevant types of clique and hub. To start creating this, I have listed some of the forms of "casting" (broad and narrow):

- broadcasting – every entry appears on a "showall" aggregation page that lists the latest publications from the whole system;

- segmented broadcasting, with entries appearing only to readers with certain membership status (eg student only, university member only);

- directory focussed broadcasting – an entry appears in "showall", but the author is writing with consideration of one of the groups represented by an aggregation page in the blog directory;

- tags based broadcasting – author targets their entry to people who are likely to be viewing all entries with a known shared tag;

- Google targeted broadcasting;

- narrowcasting to a limited known predefined group, controlled by privacy controls.

- narrowcasting to a limited group, controlled by privacy controls and "favourites" subscription.

- narrowcasting in which the privacy permissions are set to allow anyone, but the author tells specific people (often family and friends) to look at the entry (often by email) – added following Graham's suggestion.

And then we will need some questions that we can use to work out which of these are being used, and to what effect. For example:

- did the author consider the mode of casting – the audience?

- who did they consider the audience to be?

- did this affect what they wrote?

- were there instances in which they changed what they planned to write because of the mode of casting?

- were there instances in which they changed the mode of casting because of what they wrote.

If you are interested in joining in with this research, please contact me

October 14, 2005

Presentation of blogs at Oxford Brookes

I just did a presentation for really nice clever people at Oxford Brookes.

What a great day.

(This entry is part of my demo).

June 20, 2005

Analogy of the week: how to get academics and students doing new things with IT

Following the success of the Warwick Shootout film making competition, i've been thinking about how holding such showcase exciting events may be a good way of engaging the academic community in e-learning.

An analogy: become someone who is known to hold really good theme parties, to which the best people want to be invited. Next, get them involved a little in organising your parties and coming up with the ideas (which will be recognized as a cool thing to do). Then, respond with grace when they start organising their own parties along those lines, claiming that it was their idea in the first place.

June 13, 2005

What is a university?

Considered with the methodology that Manuel De Landa employs in A Thousand Years of Non-linear History .

A university consists of many smaller bodies, some more formal than others, some more hierarchical than rhizomatic, networked or meshworked. These bodies attract, pass around and process the incoming streams of energy that sustain and extend the bodies. There are multiple streams. including the annual input and turnover of students, research funding and projects, academic careers, and technical and administrative mechanisms (including external legislation). As the streams are diverted and processed, the various bodies rely upon and interfere with each other, often bringing the separate streams into contact. Each individual stream also has three aspects, each of which is dependent upon the other through often complex connections. The three aspects are cash, creative opportunity, and affirmation of individuality (always a collaborative and tribal process). These three aspects feed and sustain the bodies.

June 08, 2005

The Conceptual Failure of Higher Education Policy, Part One: Quality Assurance and Taxonomization

The first of a two part essay that reconsiders the nature and purpose of higher education and academic activity. Starting with a consideration of the neo-conceptual technical entities currently defining the debate, and considering their implications and limitations. Leading to the conclusion that a philsophical reconsideration of higher education is necessary.

Over the last week I have been engaged in an online debate with some of the key players in the development of new and exciting technologies that promise some radical changes in the British education system. Initially, my challenge was for a justification of the effort currently being put into making interoperable systems underpinned with universally defined schemas and taxonomies. Along the way, this debate has highlighted the different conceptions of the purpose and nature of education, especially higher education, forming often unstated assumptions guiding these developments. It has become clear that some of these assumptions may be contradictory. Whilst others are certainly not shared by the key actors involved. The most significant conflict being that between students and education providers. It is argued that the former are increasingly only interested in attaining a certain grade, whilst the latter are increasingly focussed upon providing a richer and more relevant set of skills and abilities during the educational process, regardless of the actual grade achieved. This may be seen as a basic contradiction within British higher education.

Lets try and get out of the quandary then, or at least try to understand it. My conjecture is this: British universities are still culturally powerful enough to redefine the purpose of the education that they offer, and to achieve a consensus amongst staff, students and the wider public. But they are failing to do so, and this is due to a conceptual failure.

There is in fact a remarkable political, cultural and commercial alliance calling for this 'revolution' to happen. It is almost dogmatically accepted that to maintain our economic position we must occupy the role of 'innovator' and 'inventor'. In fact we must be world leaders in 'creativity'. This is, in part, a response to the ease with which manufacturing processes can now be replicated anywhere in the world, along with a belief that the forces behind that change (invention of products and markets) are still beyond the third-world countries to which production has migrated (this is itself a myth, but that doesn't undermine the argument behind the calls for change). It is also a response to the perception that, as Ken Robinson has stated (Out of Our Minds: Learning to be Creative, Capstone 2001), the global rate of change is increasing all of the time, and therefore societies and economies must become better at dealing with change. This is understood to mean that we need to become dynamic people, a society whose expertise is in change itself. And in order to become such a society, we need an education system that teaches creativity, independence, team-working, innovation, self-reflection, and all kinds of 'skills' towards the top end of Bloom's taxonomy.

But this is just not happening. Or at least we can say that there is a tendency to demand and supply a simpler, less active education process. A process closer to the transmit-consume-repeat loop of the stereotypical American higher education that we deride so much (of course that is just a stereotype). As Scott Wilson argues (see comments in a previous entry in my blog), for some time British students have been overtly degree-grade focussed. Of course in reality the grade matters, no one denies that. But only as an indicator of the quality of the process carried out to achieve the grade. What we are seeing is the connection between the result and the process becoming weakened, in reality and in the conceptual model that students have of the educational process. This is confirmed to me constantly in discussions with both students and staff concerning the use of IT to improve the process. We have means for improving research, study and PDP skills of all kinds. But unless those activities contribute directly to the end product grade, with extra marks being available, students are reluctant to take part. Alarmingly, last week I had an interview with a student who confirmed that even in a module concerned principally with teaching research skills, the students are entirely focussed on the exam and not on the skills.

It may be useful for us to track back in time to the point at which things started to go wrong. Go back to the time when the current system was adequate. A relatively small and closely connected sector of British society were able to go to university. That minority all went through pretty much the same experience, with the same result in mind, at a small group of institutions. They then graduated into positions appointed by people who themselves had been through that process. They didn't need a detailed breakdown of the meaning of a 2.1 from Oxford. They already knew exactly what that meant. And then all of a sudden we move to a situation in which the majority of people are expected to complete a degree. And furthermore, the diversity of those degrees, both in the subjects covered and the methods used (related to the great number of institutions), necessarily expanded beyond any one person's ability to conceive. But we didn't change the grading system, or the nature of the academic process, in order to cope with that expansion. We still expect a simple degree grade to be universally meaningful in the way it was before the expansion. And that just doesn't work. But unfortunately, we have created several generations for whom simple end-product quantification is the only means for expressing both results and the objectives employed in the course to those results.

As an aside, consider the response of our short-termist politicians during these developments. Consider that, due to the nature of our political system, their sole aim is to achieve quality assurance (or at least the appearance of quality) at the lowest possible cost, in the shortest possible time. And so if they can say that the number of students achieving a high grade has increased, they will assume that quality is being achieved, and they will carry on with this claim until it is already quite clear that quality is not actually increasing with the rise in grades, and in fact may actually be falling. At which point they will switch to the next least costly system for claiming quality assurance (see below). Does that tune remind you of the early days of the Blair regime?

I am sure that we can say that the set of concepts used to understand, determine and communicate academic processes is extremely impoverished. It may even be limited to some vague notions about the differences between academic disciplines, along with the obviously meaningless degree rating system. However, that is already a well established argument. The really important question is this: do we have a richer and more effective set of concepts that can meaningfully express the kind of education that we are aiming for?

Action is of course being taken to address the problem. We are slowly moving towards more detailed reporting of the processes that constitute a degree: transcripts. Every student may ask for a transcript of their degree. But I suspect that these will just consist of a more extensive set of reports of end-product quantifiers. In what sense would a statement that as part of my degree I have completed an optional extra Creative Writing Skills Module say much about my actual abilities? Again, unless you have yourself completed a genuinely similar module, it is quite meaningless. For a short time it may have seemed that transcripts would be the solution, as the next least costly means for guaranteeing and communicating academic quality. But in reality, perhaps not.

For the next solution to the problem, we must move up a level in descriptive sophistication and cost: the ePortfolio. Essentially, an ePortfolio should be the online equivalent of a folder full of examples and evidence. In theory it provides the detail and contextualisation necessary to give meaning to the reports of end-product attainment. It could well be seen as an extension of the kind of narrative that a student may usefully give verbally about themselves and their studies. It is an extension in that it is hyperlinked, and is populated with selected content over a period of time from a wide variety of sources, and with annotations added to that content. The production of the ePortfolio may also be automated and 'scaffolded' (meaning that the student is given a structure to fill in, with the aim of teaching them how to independently create such a structure). The automation of an ePortfolio is not simply done to save the student time and effort. Rather, it is there to impose something of the institution and the wider educational establishment into the ePortfolio, into the student's narrative. Automation allows for the inclusion of authoritative elements guaranteeing claims made. It is also intended to ensure that the structure of the ePortfolio, in terms of the order and relations between a predefined set of descriptors (what they call a taxonomy), is codified according to a predetermined machine readable pattern. Imagine the result if we all did have such interoperable ePortfolios held within a government computer somewhere. Imagine that one of the descriptors were 'creative act', and that this is appended to a sub set of learning activities. A civil servant could do a single query to discover the sum total of creativity in the UK over the last year. Quality. Or at least, quality spin.

This last development, the taxonomization of learning (of which the interoperable ePortfolio, the VLE and other learning technologies are merely Trojan horses), brings us up to the present. It offers to be the next least expensive solution to the problem of quality assurance and quality reporting in higher education. Politicians like it, as it gives standardization and quality assurance, but without them having to do very much. The work is devolved to the learners themselves. The technologists promote it because it gives them a chance to get some really neat tools deployed at every point in the education system. But should we in higher education be as enthusiastic? At first it seems to solve the problems outlined above. It will provide a means of precisely stating the nature and value of degrees in relation to school and college education, and onwards to careers and CPD. It gives the possibility for that restatement of higher education with which this paper began, reaching the higher levels of Bloom's taxonomy (the activities of 'higher' intelligence). And furthermore, it will refocus the student on the acquisition, during their studies, of those higher skills. Hoorah for taxonomies.

And so we have the construction of what might be a univocal language of learning. Within the educational space over which it is placed, any single activity may be codified, transmitted to another seemingly un-connected location, and de-coded to make perfect sense. But first of all we must learn the language. And when I say we, I mean everyone. If we are seeking to encourage independent, self-directed, reflective learning, that everyone includes the learners themselves. They must all speak the taxonomy. Perhaps in a simplified and filtered dialect, but always with their goals, processes, reasons, progress and achievements translatable into the taxonomy. It acts as the educational infrastructure, the architecture of learning with which even a 2.1 from Oxford (as an example of an abstract educational entity) may be meaningfully coded for the consumption of the Secretary of State for Education, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, the Daily Mail or the 'wider electorate'.

But what kind of architecture is it? A kind of prefabrication system, with components that can be taken anywhere and reconstructed according to the specifications guiding their placement and interconnection. A perfectly portable and reproducible system, that can be easily communicated. And furthermore, as the system has been intelligently designed with components that encapsulate certain 'constructivist' concepts of learning, wherever such a building is assembled, the learner cannot help but learn in the right way, according to those concepts. The architecture as such is axiomatic. Or in edu-speak, it provides the scaffolding for good learning.

Scaffolding is a good metaphor. It wraps around (and sometimes within) a building in the process of construction. The scaffolding in a way shapes the building, guides it, but becomes invisible. It gets assembled, dismantled and extended where appropriate as the building grows. And at some point, is no longer required, as the pattern to which it has been working becomes internalized into the building. Then, the more difficult fine detail of the building can be worked upon.

Unfortunately, it seems that students often don't understand that we want them to be concerned with the building and not the scaffolding. This might be a result of the following:

- understanding and navigating the scaffolding is itself a major achievement;

- but understanding the scaffolding is still a quicker win than actually creating the building;

- everyone has the same experience of the scaffolding, but they are all creating different buildings, so there's less of a shared understanding of the building;

- it's the scaffolding that is provided by the authorities, not the building;

- consequently, we end up rewarding them for understanding the scaffolding, not for the building or for the process of building;

- so at some point along the way, the building is forgotten and all we are left with is the scaffolding.

Or in other words, the ability to speak the taxonomy, to carry out activities that are validated through assigning them to nodes in the taxonomical tree, becomes the most important aim of learning. In this way, 'working to the assessment criteria' takes on a new meaning, with the outcomes being better documented and more thoroughly standardized, but at the same time increasingly vacuous and self-serving. The end of taxonomizing is for it to say too much about itself, about its order, and nothing about concepts that connect and do work beyond that order. Taxonomies are filled with words that eventually act too much as order-words and too little as concepts. And that leaves us in a position little advanced from the conceptual failure with which we started. The politicians and technologists may be happy for a while, but the questions will return. What is higher education about? What are its results? Where is its quality? What difference does it make?

In the second part of this essay I will look more closely at the nature of the various academic processes of science, arts and philosophy. I will argue that in order to recognize, reward and encourage these activities, a new set of concepts is required. Concepts more precise and more closely related to the many distinct activities within the various disciplines. This moves in the opposite direction of much recent educational theorizing. Away from generality of taxonomy and towards the value located in each discipline. But at the same time, I will aim to describe an absolutely minimal set of concepts that do provide some common ground between the disciplines, albeit not that of the short-termist politicians and their desire for simple quality assurance. This will itself require a reconsideration of the question 'what is a concept?' – the answer itself being closer to real academic activity, and the production of conjectures, design patterns, working assumptions, and critical and creative thought embedded and emergent from more vital academic ecologies.

Robert O'Toole

Robert O'Toole

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading