Roma or Perseus? The ambiguity of images

|

| Coin of Roman Macedonia, c. 168 BC |

This week I returned to thinking about Roman Macedonia, and the unusual series of bronze coins struck by Roman quaestors there (an earlier post on the topic can be found here).The first series of bronze coinage struck after the Roman conquest of Macedonia in 168 BC was issued by the quaestor Gaius Publilius, who struck the unusual type pictured right (MacKay 1). Catalogues identify the obverse of this type as Roma, with the reverse giving the name of the province (Macedonia) in Greek, as well as the name and title of the questor (ΜΑΚΕΔΟΝΩΝ ΤΑΜΙΟΥ ΓΑΙΟΥ ΠΟΠΛΙΛΙΟΥ).

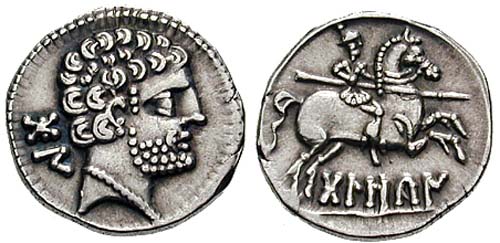

To a Roman audience, the type is Roma, similar to representations of the goddess shown on Roman denarii. But the image is also extremely similar to the iconography of the hero Perseus, who was shown on the bronze coins of the Macedonian kings during the Hellenistic period (shown below right. Philip V even presented himself as Perseus on silver coinage). This raises the question: would a Macedonian, glancing at the coin as they used it, have recognised 'Roma', or would they have seen Perseus, a continuation of the monetary tradition in the region?

|

| Coin of Philip V, Macedonia, 221-179 BC |

Images can have multiple associations, and this is particularly the case for numismatic imagery. Unlike other public monuments, which are erected within a particular landscape or context determing the way they are 'viewed', coinage is a medium in motion, being seen by different users in a wide variety of different contexts. This, in turn, results in a broad spectrum of possible associations and interpretations. The ambiguous nature of the image here may have been intentional - there is no obverse legend identifying the image for the viewer. Thus this image may have been intentionally chosen by the Romans for its ambiguity - it had meaning and significance for both Romans and Macedonians, but this meaning was not necessarily the same for both groups. One image, with mutually incompatable possible interpretations, may have served as a focal point in bringing together two different cultures. Indeed, the fact that the existing Macedonian currency carried portraits of Perseus may have actually inspired the Romans in adopting the 'Roma' type for their coinage in the region, explaining why Roma appears here and not in other areas under Roman control in this period.

So is the image Roma or Perseus? The answer all depends on one's perspective....

(Images above reproduced courtesy of Classical Numismatic Group Inc., (www.cngcoins.com)

Clare Rowan

Clare Rowan

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

The department of Coins and Medals at the BM is easy to miss: beside an indiscrete steel door at the rear of the money gallery, there is a bell which, when pressed, announces your arrival to the sound of trumpets. Inquisitive tourists watch as you enter. Then, as the door is locked, you realise that you have stepped into a giant safe: every room is isolated, while security cameras inspect your movements from above. This is unsurprising, considering the amount of gold and silver which now lies within snatching distance. Any would-be burglar, however, should consider the following before he melts down his loot – a haul of ancient coinage is today worth much more than the sum of its parts.

The department of Coins and Medals at the BM is easy to miss: beside an indiscrete steel door at the rear of the money gallery, there is a bell which, when pressed, announces your arrival to the sound of trumpets. Inquisitive tourists watch as you enter. Then, as the door is locked, you realise that you have stepped into a giant safe: every room is isolated, while security cameras inspect your movements from above. This is unsurprising, considering the amount of gold and silver which now lies within snatching distance. Any would-be burglar, however, should consider the following before he melts down his loot – a haul of ancient coinage is today worth much more than the sum of its parts.

as Rome admired Greece for its higher culture, but was afraid of how it could influence changes in the political and social structures of the empire. Eventually the two cultures mixed during the Roman conquest and we can see that a balance was struck between the reverence shown to the Roman Emperors and provincial imagery. This balance can be seen particularly in the coinage of Ephesus where the majority of coins show the Roman Emperor on the obverse, and local images emphasised civic pride on the reverse.

as Rome admired Greece for its higher culture, but was afraid of how it could influence changes in the political and social structures of the empire. Eventually the two cultures mixed during the Roman conquest and we can see that a balance was struck between the reverence shown to the Roman Emperors and provincial imagery. This balance can be seen particularly in the coinage of Ephesus where the majority of coins show the Roman Emperor on the obverse, and local images emphasised civic pride on the reverse. This month's coin was chosen by Emily Morgan, a final year undergraduate. While her dissertation focused on the attitudes towards death in Greek literature, she is an avid coin collector and is passionate about expanding her knowledge of classical numismatics.

This month's coin was chosen by Emily Morgan, a final year undergraduate. While her dissertation focused on the attitudes towards death in Greek literature, she is an avid coin collector and is passionate about expanding her knowledge of classical numismatics.

the decision to bring Asclepius, the god of Medicine, to Rome was made in order to avert a pestilence against which remedies of the time were powerless. In 293 BC, following an oracle from Delphi, the Roman senate decided to bring the cult of Asclepius to the Urbs. For this purpose, they sent delegates to Epidaurus, the most famous Asclepius shrine of the time, in order to fetch one of the sacred snakes of Asclepius and carry it back to Rome on a ship. Similar epidemic outbreaks, combined with human helplessness in the face of disease explain the spread of the cult of Asclepius from the 5th c. BC onwards.

the decision to bring Asclepius, the god of Medicine, to Rome was made in order to avert a pestilence against which remedies of the time were powerless. In 293 BC, following an oracle from Delphi, the Roman senate decided to bring the cult of Asclepius to the Urbs. For this purpose, they sent delegates to Epidaurus, the most famous Asclepius shrine of the time, in order to fetch one of the sacred snakes of Asclepius and carry it back to Rome on a ship. Similar epidemic outbreaks, combined with human helplessness in the face of disease explain the spread of the cult of Asclepius from the 5th c. BC onwards.

This month's coin is chosen by Dr. Caroline Petit, a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow in Classics at Warwick who works on ancient medicine.

This month's coin is chosen by Dr. Caroline Petit, a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow in Classics at Warwick who works on ancient medicine.

of the PROVINCIA DACIA coin series. PROVINCIA DACIA was a local coinage in the middle and lower Danube area during the 3rd century AD. It mainly circulated in the provinces of Dacia and Pannonia, as suggested by site finds. A close analogy can be established with another roughly contemporary bronze coinage P M S COL VIM (Provinciae Moesiae Superioris Colonia Viminiacum), which was issued at Viminacium in Moesia Superior between AD 239 and 257. The research of C. Gãzdac suggests that the main role of these coins was to supply the army. The PROVINCIA DACIA coin series can therefore be closely linked with the military and their need for bronze coinage in Dacia. This hypothesis is supported by site finds from the territory of this province. For example, at the militarised site of Porolissum, 64% of the PROVINCIA DACIA coins minted during the reign of Philip I were retrieved from the territory of the fort (Á. Alföldy-Gãzdac, C. Gãzdac, The coinage ‘PROVINCIA DACIA’ – a coinage for one province only? (AD 246-257), in Acta Musei Napocensis, 39-40/I, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2002-2003 (2004), p. 247-258).

of the PROVINCIA DACIA coin series. PROVINCIA DACIA was a local coinage in the middle and lower Danube area during the 3rd century AD. It mainly circulated in the provinces of Dacia and Pannonia, as suggested by site finds. A close analogy can be established with another roughly contemporary bronze coinage P M S COL VIM (Provinciae Moesiae Superioris Colonia Viminiacum), which was issued at Viminacium in Moesia Superior between AD 239 and 257. The research of C. Gãzdac suggests that the main role of these coins was to supply the army. The PROVINCIA DACIA coin series can therefore be closely linked with the military and their need for bronze coinage in Dacia. This hypothesis is supported by site finds from the territory of this province. For example, at the militarised site of Porolissum, 64% of the PROVINCIA DACIA coins minted during the reign of Philip I were retrieved from the territory of the fort (Á. Alföldy-Gãzdac, C. Gãzdac, The coinage ‘PROVINCIA DACIA’ – a coinage for one province only? (AD 246-257), in Acta Musei Napocensis, 39-40/I, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2002-2003 (2004), p. 247-258). The importance of this coin, struck in the first year of the local era, is suggested by the high volume of this coinage in Dacia during the reign of Philip I (estimated by C. Gãzdac at almost 40%), and by its intended audience. The mint where this specimen was struck remains debatable. However, recent scholars have provided convincing arguments for Apulum.

The importance of this coin, struck in the first year of the local era, is suggested by the high volume of this coinage in Dacia during the reign of Philip I (estimated by C. Gãzdac at almost 40%), and by its intended audience. The mint where this specimen was struck remains debatable. However, recent scholars have provided convincing arguments for Apulum.

Loading…

Loading…