A hoard of 201 antoniniani found in Eretria (Greece)

|

| View of modern Eretria and its ancient acropolis |

In 2011, a hoard of 201 antoniniani minted between AD 219 and 254 was found in Eretria on the island of Euboea during the excavations of the Swiss School of Archaeology in Greece (ESAG). So far, this is one of the biggest hoards of this time found in Greece, which makes it all the more interesting.

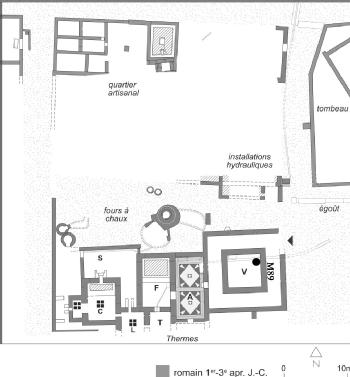

The hoard was found in the Roman bath building, buried next to a wall forming the impluvium in a peristyle courtyard giving access to the proper bath rooms.

Most of the coins belong to issues of the reign of Gordian III (238-244: 80 coins), Philip I (244-249: 86 coins) and Trajan Decius (249-251: 30 coins), with only a few minted under Elagabalus (218-222: 2 coins), Trebonianus Gallus (215-253: 2 coins) and Gallienus (253-268: 1 coin).

This kind of coin distribution appears to be characteristic of a number of hoards from Greece, Turkey or the Balkans ending under the joint reign of Valerian and Gallienus (253-260): Greece 1980 (254), Caesarea (255-256), Iasos (257-258) and Pergamum (258-259). Some hoards of this period like Göktepe (253) or Singidunum (254) still contain denarii, but none was recorded in the Eretria hoard, which explains why the proportion of coins minted before 238 remains insignificant.

|

|

Plan of the Roman bath of Eretria. The hoard was found against wall M 89 (© ESAG) |

While there are fewer coins of Trajan Decius (249-251) than his predecessors in quite a few of the hoards mentioned here, including the one from Eretria, it is possible to show that this is due to the shortness of his reign rather than to a reduction in the rate of hoarding. However, the rate of hoarding definitely slows down under Trebonianus Gallus (251-253) which seems surprising for hoards ending towards the end of Valerian and Gallienus' joint reign.

A study of the silver hoards buried in Greece during the 3rd century AD reveals that the coins in circulation in that region were replaced by new issues on a much faster basis than at the northwestern peripheries of the Empire (e.g. Britain).

The Eretria hoard appears to be typical of hoards ending between 251 and 264 that contain mainly issues minted between 238 and 251 (Mytilene, Cnossus, Greece 1980, Patras 1976, and Patras 1982). However, these issues seem to have almost completely disappeared from hoards buried after 265, towards the end of Gallienus' sole reign, when the antoniniani started to become heavily debased (Corinth 1930, Orchomenos, Chaeronea, Attica, Salamis, Athens 1955, Athens 1956, and Corinth 1936).

As most of the Greek hoards mentioned here are small in size (under 100 coins), they seem to reflect the daily coin circulation, which saw the disappearance of older, better coins from daily use.

So far, the Eretria hoard is the only one in Greece to show a small percentage of antoniniani minted in Antioch under Gordian III. As a general rule, the mint of Rome remains the only noteworthy supplier of coins in Greece up to Trebonianus Gallus. This changes under Valerian and Gallienus, when the coin supply from oriental mints increased suddenly to levels well above 50 %. The proportion of the Balkan mints however remained small at all times.

|

|

| Hoard in situ (© ESAG) | Hoard being removed during excavation (© ESAG) |

Dr Marguerite Spoerri Butcher is Associate Fellow of the University of Warwick and she works for the Swiss School of Archaeology in Greece.

Dr Marguerite Spoerri Butcher is Associate Fellow of the University of Warwick and she works for the Swiss School of Archaeology in Greece.

She has published, jointly with A. Casoli, a complete study of the Eretria hoard: «Un trésor d’antoniniens trouvé à Erétrie en 2011 questions de circulation monétaire en Grèce au milieu du IIIe siècle», Revue Suisse de Numismatique 91, 2012, p. 111-206, which can be downloaded here .

.

Clare Rowan

Clare Rowan

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

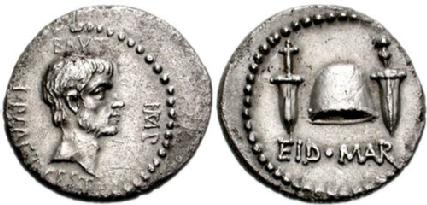

It was minted by Marcus Iunius Brutus in northern Greece during the late summer of 42 BC, for he had fled Rome after the assassination. Soon after, at the second Battle of Philippi, Brutus and his fellow conspirators were defeated by Mark Antony and Octavian, and he committed suicide. The obverse of the coin presents a bareheaded Brutus, with the legend “Brutus, Imperator, Lucius Plaetorius Cestianus (moneyer).” Republican coins did not display portraits of living men, but on this denarius Brutus included his own effigy and his title of Imperator, more in line with the coins of Julius Caesar, the man he had killed for supposedly wanting to be king. The reverse shows the cap of liberty (pileus), which was traditionally given to slaves on manumission, between two daggers. The chilling legend underneath reads EID(ibus) MAR(tiis)(Ides of March). Therefore, on one side of the coin Brutus claims to have liberated the fatherland and saved the Republic, but on the other side he presents himself as a general in the style of Julius Caesar. A few years later, Octavian (Augustus) would succeed in using both kinds of self-advertisement to create the Principate, marking the end of the Republic and the beginning of the Roman Empire.

It was minted by Marcus Iunius Brutus in northern Greece during the late summer of 42 BC, for he had fled Rome after the assassination. Soon after, at the second Battle of Philippi, Brutus and his fellow conspirators were defeated by Mark Antony and Octavian, and he committed suicide. The obverse of the coin presents a bareheaded Brutus, with the legend “Brutus, Imperator, Lucius Plaetorius Cestianus (moneyer).” Republican coins did not display portraits of living men, but on this denarius Brutus included his own effigy and his title of Imperator, more in line with the coins of Julius Caesar, the man he had killed for supposedly wanting to be king. The reverse shows the cap of liberty (pileus), which was traditionally given to slaves on manumission, between two daggers. The chilling legend underneath reads EID(ibus) MAR(tiis)(Ides of March). Therefore, on one side of the coin Brutus claims to have liberated the fatherland and saved the Republic, but on the other side he presents himself as a general in the style of Julius Caesar. A few years later, Octavian (Augustus) would succeed in using both kinds of self-advertisement to create the Principate, marking the end of the Republic and the beginning of the Roman Empire.  Florence, Alessandro de Medici, was murdered by his cousin Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco (Lorenzino or Lorenzaccio). Although the ultimate motives of Lorenzino are a subject of debate, his attempt to identify with Brutus and the model of classical tyrannicide is clear. In his Apologia he claims to have rid Florence of a tyrant. Also, Lorenzino followed the design of the Brutus denarius in his bronze medal, but in this case the daggers and pileus are inverted. He is even depicted wearing Roman dress and the date of the murder is VIII.ID.IAN, or eight days before the Ides of January.

Florence, Alessandro de Medici, was murdered by his cousin Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco (Lorenzino or Lorenzaccio). Although the ultimate motives of Lorenzino are a subject of debate, his attempt to identify with Brutus and the model of classical tyrannicide is clear. In his Apologia he claims to have rid Florence of a tyrant. Also, Lorenzino followed the design of the Brutus denarius in his bronze medal, but in this case the daggers and pileus are inverted. He is even depicted wearing Roman dress and the date of the murder is VIII.ID.IAN, or eight days before the Ides of January. This month’s coin was chosen by Desiree Arbo, a first year PhD student. Desiree’s research focuses on the reception of Rome in 19th century Paraguay (South America). She is interested in the way elite thinkers used classical imagery and the idea of Rome in constructing the Paraguayan nation.

This month’s coin was chosen by Desiree Arbo, a first year PhD student. Desiree’s research focuses on the reception of Rome in 19th century Paraguay (South America). She is interested in the way elite thinkers used classical imagery and the idea of Rome in constructing the Paraguayan nation. Pergamum as part of his tour around Asia Minor. Ancient historians state that the reason for this visit was because he sought healing and relief from dreams in which he was being chased by his father Septimus Severus and brother Geta, whom he was accused of murdering. As the healing god of antiquity, Asclepius was a logical choice to supplicate for salvation. This medallion is part of a series which was minted by Pergamum in AD 211-217. The series documents the emperor’s advent and his ritual movements through the city. This medallion shows Caracalla supplicating Asclepius in front of his temple. In between the god and the emperor stands a bull waiting to be sacrificed to the god and an attendant with a raised axe. This medallion is especially important as it shows the significance the emperor attached to worshipping Asclepius and the belief that this god could save him from his torment. It also shows the importance the city attached to the emperor’s visit as the polis struck these issues and also issued another series commemorating the visit some years later. This medallion also shows the advantages of imperial benefaction upon a city as the coin’s legend mentions that Pergamum was the first who was ‘three times neokoros’ in Asia Minor. This term was used to indicate a city which had a temple of the imperial cult and Pergamum was the first in the region to have three temples of emperors. Other coins from this series show Asclepius and Caracalla sharing a temple, a practise not uncommon in Asia Minor, again indicating Caracalla’s patronage of this god.

Pergamum as part of his tour around Asia Minor. Ancient historians state that the reason for this visit was because he sought healing and relief from dreams in which he was being chased by his father Septimus Severus and brother Geta, whom he was accused of murdering. As the healing god of antiquity, Asclepius was a logical choice to supplicate for salvation. This medallion is part of a series which was minted by Pergamum in AD 211-217. The series documents the emperor’s advent and his ritual movements through the city. This medallion shows Caracalla supplicating Asclepius in front of his temple. In between the god and the emperor stands a bull waiting to be sacrificed to the god and an attendant with a raised axe. This medallion is especially important as it shows the significance the emperor attached to worshipping Asclepius and the belief that this god could save him from his torment. It also shows the importance the city attached to the emperor’s visit as the polis struck these issues and also issued another series commemorating the visit some years later. This medallion also shows the advantages of imperial benefaction upon a city as the coin’s legend mentions that Pergamum was the first who was ‘three times neokoros’ in Asia Minor. This term was used to indicate a city which had a temple of the imperial cult and Pergamum was the first in the region to have three temples of emperors. Other coins from this series show Asclepius and Caracalla sharing a temple, a practise not uncommon in Asia Minor, again indicating Caracalla’s patronage of this god.  This month’s coin was chosen by Ghislaine van der Ploeg, a second year PhD student. Ghislaine’s research focusses on the cult of Asclepius and its dissemination. Coins, as well as inscriptions, art, and architecture are vital in this, as each dedication gives a unique perspective on the ways in which the cult spread and the factors which were responsible for this.

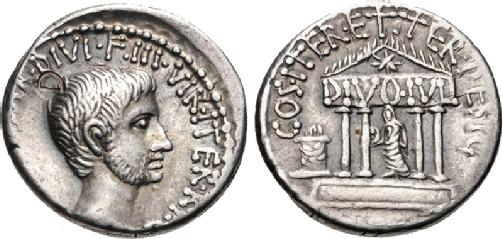

This month’s coin was chosen by Ghislaine van der Ploeg, a second year PhD student. Ghislaine’s research focusses on the cult of Asclepius and its dissemination. Coins, as well as inscriptions, art, and architecture are vital in this, as each dedication gives a unique perspective on the ways in which the cult spread and the factors which were responsible for this. and depicts a mournful Octavian on the obverse, and the unfinished temple of Divus Julius on the reverse, and is a great example of the propaganda-tactics Augustus employed to get into a position of such power. This coin is a homage to Augustus’ relationship with the late Julius Caesar, and a display of his divine heritage. The obverse shows a young Augustus – the youthful image that would remain of him past his death, a contrast to previous realistic and less flattering portraits. He is shown here as bearded, which tells us that he is still in mourning, though his adoptive father died eight years previously in 44 BC. The legend reads ‘Imperator Caesar, Son of the Deified, Triumvir for the establishment of the Commonwealth for a second time’, and here the DIVI F (Son of the Deified) is emphatic above his head, and links very well to the reverse. The reverse shows the temple of the Divine Julius, which though begun in 42 BC (upon the spot of Caesar’s cremation), was not inaugurated until 29 BC. The legend ‘Divine Julius’ upon the temple is bold and eye catching.

and depicts a mournful Octavian on the obverse, and the unfinished temple of Divus Julius on the reverse, and is a great example of the propaganda-tactics Augustus employed to get into a position of such power. This coin is a homage to Augustus’ relationship with the late Julius Caesar, and a display of his divine heritage. The obverse shows a young Augustus – the youthful image that would remain of him past his death, a contrast to previous realistic and less flattering portraits. He is shown here as bearded, which tells us that he is still in mourning, though his adoptive father died eight years previously in 44 BC. The legend reads ‘Imperator Caesar, Son of the Deified, Triumvir for the establishment of the Commonwealth for a second time’, and here the DIVI F (Son of the Deified) is emphatic above his head, and links very well to the reverse. The reverse shows the temple of the Divine Julius, which though begun in 42 BC (upon the spot of Caesar’s cremation), was not inaugurated until 29 BC. The legend ‘Divine Julius’ upon the temple is bold and eye catching.

where they encountered the army of the Hindu king Porus. At the River Hydaspes Alexander managed to defeat his opponent in a closely fought battle across the monsoon-swollen river. Despite this victory Alexander’s army would advance little further into India. Daunted by the skill and number of the native people and terrified by their elephants, the Macedonians mutinied and demanded to return westwards, to which Alexander eventually agreed. After many trials and tribulations the Macedonian army ultimately returned to Babylon where Alexander would live out the last few months of his life before dying suddenly and mysteriously on the 10th June 323 BC.

where they encountered the army of the Hindu king Porus. At the River Hydaspes Alexander managed to defeat his opponent in a closely fought battle across the monsoon-swollen river. Despite this victory Alexander’s army would advance little further into India. Daunted by the skill and number of the native people and terrified by their elephants, the Macedonians mutinied and demanded to return westwards, to which Alexander eventually agreed. After many trials and tribulations the Macedonian army ultimately returned to Babylon where Alexander would live out the last few months of his life before dying suddenly and mysteriously on the 10th June 323 BC. Until then, the island had been an important part of the Ptolemaic Empire and had been ruled by the Ptolemies since c. 312 BC. From 58 BC, Cyprus was governed by Rome until Julius Caesar gifted the island to Cleopatra in c. 48-47 BC. The restoration of Ptolemaic power was also later confirmed by Marc Antony. As the final foreign stronghold to be confiscated from the Ptolemies, the annexation of Cyprus was a defining moment, contributing to the demise of the dynasty. The imagery depicted on this coin reflects the tactical decisions made by Cleopatra VII, the last ruling Ptolemy, who found herself trying to maintain power and authority over her lands during this period of political upheaval by aligning herself politically first with Julius Caesar, and then later with Marc Antony. On the front of the coin is an idealized portrait of Cleopatra as Aphrodite, the most important deity of Cyprus, whose sanctuary at Palaipaphos was famed in antiquity as the birthplace and home of the great goddess. On the coin, Cleopatra is also shown with her son by Julius Caesar, Caesarion, who is depicted as Eros in front of her. It is thought that the coin was issued to celebrate the birth of Caesarion. By appearing as Aphrodite and Eros, Cleopatra appears to be aligning herself with the ideology of the Caesars as being descended from Venus (Aphrodite's Roman counterpart) in order to secure a future for herself and her son, perhaps as Caesar's heir, in a very local context. With the suicides of Antony and Cleopatra following their defeat at the hands of Octavian at Alexandria, Cyprus along with Egypt fell under the control of Rome once and for all. The image of Aphrodite, represented as a sacred cone rather than in anthropomorphic form, remained an important symbol of Cyprus and was depicted on coinage minted in Cyprus under future Roman Emperors.

Until then, the island had been an important part of the Ptolemaic Empire and had been ruled by the Ptolemies since c. 312 BC. From 58 BC, Cyprus was governed by Rome until Julius Caesar gifted the island to Cleopatra in c. 48-47 BC. The restoration of Ptolemaic power was also later confirmed by Marc Antony. As the final foreign stronghold to be confiscated from the Ptolemies, the annexation of Cyprus was a defining moment, contributing to the demise of the dynasty. The imagery depicted on this coin reflects the tactical decisions made by Cleopatra VII, the last ruling Ptolemy, who found herself trying to maintain power and authority over her lands during this period of political upheaval by aligning herself politically first with Julius Caesar, and then later with Marc Antony. On the front of the coin is an idealized portrait of Cleopatra as Aphrodite, the most important deity of Cyprus, whose sanctuary at Palaipaphos was famed in antiquity as the birthplace and home of the great goddess. On the coin, Cleopatra is also shown with her son by Julius Caesar, Caesarion, who is depicted as Eros in front of her. It is thought that the coin was issued to celebrate the birth of Caesarion. By appearing as Aphrodite and Eros, Cleopatra appears to be aligning herself with the ideology of the Caesars as being descended from Venus (Aphrodite's Roman counterpart) in order to secure a future for herself and her son, perhaps as Caesar's heir, in a very local context. With the suicides of Antony and Cleopatra following their defeat at the hands of Octavian at Alexandria, Cyprus along with Egypt fell under the control of Rome once and for all. The image of Aphrodite, represented as a sacred cone rather than in anthropomorphic form, remained an important symbol of Cyprus and was depicted on coinage minted in Cyprus under future Roman Emperors.

In 49 BC Julius Caesar struck a coin series in his name showing an elephant trampling a snake on one side, and the emblems of his position as chief priest of Rome on the other. Scholarship remains divided on what Caesar meant by the elephant and snake imagery, but, having robbed the state treasury in Rome, Caesar was able to mint one of the largest issues of coinage that Rome had ever seen. Four years later a supporter of Caesar, Aulus Hirtius, struck coinage showing exactly the same imagery, replacing Caesar's name with his own. Hirtius also added an eigth book to Caesar's account of his Gallic Wars, and played a key role in the civil wars that followed Julius Caesar's assassination. This particular coin is significant since it demonstrates that the imagery Caesar chose for his coinage was viewed, remembered,and then redeployed in different contexts. Here Hirtius uses the imagery to underline his connection to the Caesarian cause. It is evident that Roman coins were 'monuments in miniature', intended to communicate ideologies as well as to serve as a means of payment and exchange. The image of the elephant and the snake was later adopted as a symbol of Roman power in Gaul and Africa. The iconography of Julius Caesar was transformed into an imagery of Empire. (To see the original coin of Julius Caesar, click

In 49 BC Julius Caesar struck a coin series in his name showing an elephant trampling a snake on one side, and the emblems of his position as chief priest of Rome on the other. Scholarship remains divided on what Caesar meant by the elephant and snake imagery, but, having robbed the state treasury in Rome, Caesar was able to mint one of the largest issues of coinage that Rome had ever seen. Four years later a supporter of Caesar, Aulus Hirtius, struck coinage showing exactly the same imagery, replacing Caesar's name with his own. Hirtius also added an eigth book to Caesar's account of his Gallic Wars, and played a key role in the civil wars that followed Julius Caesar's assassination. This particular coin is significant since it demonstrates that the imagery Caesar chose for his coinage was viewed, remembered,and then redeployed in different contexts. Here Hirtius uses the imagery to underline his connection to the Caesarian cause. It is evident that Roman coins were 'monuments in miniature', intended to communicate ideologies as well as to serve as a means of payment and exchange. The image of the elephant and the snake was later adopted as a symbol of Roman power in Gaul and Africa. The iconography of Julius Caesar was transformed into an imagery of Empire. (To see the original coin of Julius Caesar, click  This month's coin was chosen by Clare Rowan, a research fellow in Numismatics at Warwick. As part of her research, Clare works on how coinage was used as a medium to visualise and negotiate Roman power in the provinces of the Republic. By looking at coin iconography in the Roman provinces, we are able to reconstruct how Roman control of particular regions was viewed, negogiated or rejected. Click

This month's coin was chosen by Clare Rowan, a research fellow in Numismatics at Warwick. As part of her research, Clare works on how coinage was used as a medium to visualise and negotiate Roman power in the provinces of the Republic. By looking at coin iconography in the Roman provinces, we are able to reconstruct how Roman control of particular regions was viewed, negogiated or rejected. Click

Loading…

Loading…