All 5 entries tagged Undergraduate Research

No other Warwick Blogs use the tag Undergraduate Research on entries | View entries tagged Undergraduate Research at Technorati | There are no images tagged Undergraduate Research on this blog

November 01, 2013

The YHD Coins of Judah

|

| Athenian Tetradrachm, 400-353 BC |

During the latter half of the fifth century BC, proud Athenians might have professed their coinage to be the world’s reserve currency; the ubiquitous ‘owls’ were recognised even in Persian-held territories. In the dying days of the Peloponnesian War, however, Athens found herself in both military and financial straits: to meet the costs of warfare, the citizens were reduced to plundering gold plate from the statues of Nike on the Acropolis, and the volume of newly-minted ‘owls’ entering circulation was drastically reduced. For undocumented reasons, a short time after, private and public individuals in the Persian satrapy of Judah began producing imitation coinage, featuring Athenian iconography.

Spot the Difference

Our two coins were both minted in the fourth century bc. The silver Athenian tetradrachm is an easily identifiable type: the well-defined helmeted head of Athena on the obverse; the owl, olive spray and the lettering ΑΘΕ [ΝAION] “of the Athenians” on the reverse. At first glance, the design on its counterpart, a Jewish obol, looks like a poor man’s copy. Athena’s features are somewhat oriental, and the owl has lost some fine detail. Perhaps Near Eastern die-engravers were unable to reproduce the Athenian images, or maybe, more likely, the need for a pixel-perfect replica simply didn’t exist. If official ‘owls’ were only required in the Near East and Transjordan for long-distance trading, any political significance of the images would have been lost – it was the worth of the metal that mattered.

|

| Persian YHD coin of Judah, 375-332 BC |

The clearest difference between the two coins is the reverse legend, which on the Jewish coin, is written in paleo-Hebrew and reads YHD (sometimes YHWD). This name is used in the Bible when referring to the satrapy of Judah during the Persian period; also, it is found impressed upon the handles of contemporary jars excavated in Jerusalem. Hence, the legend is openly advertising the provenance of the coin: no one is trying to ‘pass off’ this owl as an Athenian original. Similarly, the replacement of the olive spray with a lily on the reverse signifies its foreign mint: the biblical temple built by King Solomon had pillars decorated with ‘lily-work’, the lily being a traditional symbol of Jerusalem.

Small Change

Over time, especially after the conquests of Alexander the Great, the yhd coin types altered. Without apparent repercussions, the Athenian owl was replaced by a falcon; the profile of Athena by a male head. Yhd coins were never, it seems, consistent with Athenian weight standards and denominations. So we are left with the question: when they began minting, why did the Persian satraps in Judah borrow from the Athenians at all?

The answer is probably to be found in the persistent conservative trend which pervades numismatic history: in order for people to accept that something IS money, it has to LOOK like money. Athenian owls were so widespread during the latter half of the fifth century that local changes to coinage design were necessarily small, in order to preserve wider confidence in the metal’s worth. We might update the idea by imagining the suspicious glance which greets a Scottish five-pound note in Cornwall today: perhaps it is akin to the reception of a newly-minted silver coin in Jerusalem 2400 years ago, although in the ancient case, a lily rather than a thistle gives the game away.

This month's coin was chosen by Joe Grimwade, a second year undergraduate at the University of Warwick. He chose his 'Coin of the Month' after attending the British Museum's Numismatics Summer School, and is about to begin working with Warwickshire's Museum Service on their Roman coinage.

This month's coin was chosen by Joe Grimwade, a second year undergraduate at the University of Warwick. He chose his 'Coin of the Month' after attending the British Museum's Numismatics Summer School, and is about to begin working with Warwickshire's Museum Service on their Roman coinage.

Images above reproduced courtesy of Classical Numismatic Group Inc., (Electronic Auction 294, lot 306 and Electronic Auction 220, lot 194) (www.cngcoins.com)

October 01, 2013

Caracalla's "Profectio" Coin

|

| Profectio coin of Caracalla |

In AD 214, the emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninius Pius, nicknamed Caracalla after the Gallic tunic he allegedly wore, left Rome on a journey throughout the eastern provinces. The word PROFECTIO is used in Latin epigraphy to identify when an emperor sets out from Rome on a military expedition, and this word is seen on the legend on the reverse of this denarius. Minted in AD 213, this coin represents the sense of anticipation faced by Romans before the launching of such a force. Coins minted in the same year depict similar types as the coin we see here, as well as other military images such as the war god Mars. Whoever designed this coin, whether it be Caracalla himself or an imperial mint worker, clearly wanted to expose citizens to this upcoming event months in advance. Thus the coin acts as propaganda, advertising the emperor’s militaristic and proactive qualities.

The “Profectio” concept also gives the sense of beginnings being important in Roman life. The fact that the actual beginning of the expedition, rather than the expedition itself, is commemorated on this coin indicates the Romans considered the start of something to be just as worthy as the event itself. This suggests a sense of supreme confidence, as even before it has set off, the Romans believe this journey to be worthy of monumentalising through the medium of coinage, implying Romans were very optimistic about the success of their emperor and army.

The coin also reinforces the emperor’s own desire to be depicted in a military way. The type on the reverse of the coin displays Caracalla himself in military armour, carrying a spear, and it gives the impression of him personally leading the legions, represented by the standards behind him. This portrayal of himself as a great military leader is reinforced by the appearance of BRIT in the legend on the obverse of the coin, which represents “Britannicus”, or “Conqueror of the Britons”. While this title has been passed down from his father Severus (often done by Roman emperors), Caracalla himself can say he played a part in it, as he joined his father on his conquests. Accounts of the time indicate Caracalla actually played no significant role in his father’s Britannia campaign, but it is something an ordinary Roman would be unaware of. Thus even before his Profectio, Caracalla could identify himself as an experienced conqueror. Such a portrayal was probably designed to inspire support from the army, presenting the emperor as someone worth following, and whose rule they should support. However, this did not help him maintain his rule: whilst returning from his beloved Profectio, having dismounted to empty his bowels, he was murdered by a member of his Praetorian bodyguards close to the city of Edessa in Syria.

This month’s coin was chosen by David Swan, a second year Ancient History and Classical Archaeology undergraduate. David’s research interests involve Celtic, Roman and Dark Age Britain.

(Coin image above reproduced courtesy of Pecunem.com and Gitbud & Naumann)

September 01, 2013

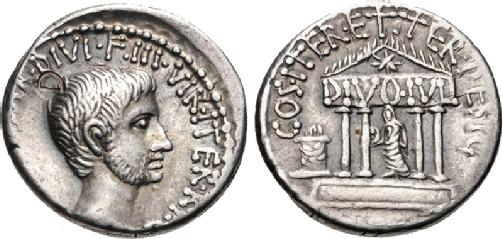

Denarius showing the temple of Divus Julius, 36 BC (RRC 540/2)

(Coin of the Month, December 2012)

This denarius was struck in 36 BC,  and depicts a mournful Octavian on the obverse, and the unfinished temple of Divus Julius on the reverse, and is a great example of the propaganda-tactics Augustus employed to get into a position of such power. This coin is a homage to Augustus’ relationship with the late Julius Caesar, and a display of his divine heritage. The obverse shows a young Augustus – the youthful image that would remain of him past his death, a contrast to previous realistic and less flattering portraits. He is shown here as bearded, which tells us that he is still in mourning, though his adoptive father died eight years previously in 44 BC. The legend reads ‘Imperator Caesar, Son of the Deified, Triumvir for the establishment of the Commonwealth for a second time’, and here the DIVI F (Son of the Deified) is emphatic above his head, and links very well to the reverse. The reverse shows the temple of the Divine Julius, which though begun in 42 BC (upon the spot of Caesar’s cremation), was not inaugurated until 29 BC. The legend ‘Divine Julius’ upon the temple is bold and eye catching.

and depicts a mournful Octavian on the obverse, and the unfinished temple of Divus Julius on the reverse, and is a great example of the propaganda-tactics Augustus employed to get into a position of such power. This coin is a homage to Augustus’ relationship with the late Julius Caesar, and a display of his divine heritage. The obverse shows a young Augustus – the youthful image that would remain of him past his death, a contrast to previous realistic and less flattering portraits. He is shown here as bearded, which tells us that he is still in mourning, though his adoptive father died eight years previously in 44 BC. The legend reads ‘Imperator Caesar, Son of the Deified, Triumvir for the establishment of the Commonwealth for a second time’, and here the DIVI F (Son of the Deified) is emphatic above his head, and links very well to the reverse. The reverse shows the temple of the Divine Julius, which though begun in 42 BC (upon the spot of Caesar’s cremation), was not inaugurated until 29 BC. The legend ‘Divine Julius’ upon the temple is bold and eye catching.

This emphasis shows just how eager Augustus was to forge a link between himself and his divine heritage through the promise of a temple. The veiled figure is holding an augur’s staff, and must be a statue of Julius Caesar.The star on the pediment has specific significance; it is the special sidus Iulium, and is yet another sign of Augustus’ divine parentage. A short few months after the infamous death of Julius Caesar, Octavian hosted the Ludi Victoriae Caesaris, which was a daring political move in his rivalry against Mark Antony. The Games were held from 20th – 28th July 44 BC, alongside a festival to honour Venus Genetrix, Caesar’s patron deity, and are famous for the star of Caesar incarnate. Octavian claimed that the comet was the deified Julius Caesar, and this was proof that he was indeed the son of a god. Suetonius tells us that the comet shone for seven successive days, and that everyone believed it was the soul of Caesar after Octavian had shouted out. Octavian wasted little time, and used this imagery of the star on coins and every statue of Caesar as a reminder of his divine right to rule. The star appears in much literature too, including Virgil’s ninth Eclogue, and the entire transformation is detailed in Ovid Metamorphoses book fifteen.

This month’s coin was chosen by Laura Christofis, a final year Classics undergraduate. Her dissertation focuses on the place of invective poems in Catullus, looking in particular at sexual and political poems.

(Coin image above reproduced courtesy of Classical Numismatic Group, www.cngcoins.com).

The 'Porus Medallion', a silver decadrachm with an image of Alexander the Great

(Coin of the Month, December 2012)

In 326 BC Alexander the Great and his army reached India  where they encountered the army of the Hindu king Porus. At the River Hydaspes Alexander managed to defeat his opponent in a closely fought battle across the monsoon-swollen river. Despite this victory Alexander’s army would advance little further into India. Daunted by the skill and number of the native people and terrified by their elephants, the Macedonians mutinied and demanded to return westwards, to which Alexander eventually agreed. After many trials and tribulations the Macedonian army ultimately returned to Babylon where Alexander would live out the last few months of his life before dying suddenly and mysteriously on the 10th June 323 BC.

where they encountered the army of the Hindu king Porus. At the River Hydaspes Alexander managed to defeat his opponent in a closely fought battle across the monsoon-swollen river. Despite this victory Alexander’s army would advance little further into India. Daunted by the skill and number of the native people and terrified by their elephants, the Macedonians mutinied and demanded to return westwards, to which Alexander eventually agreed. After many trials and tribulations the Macedonian army ultimately returned to Babylon where Alexander would live out the last few months of his life before dying suddenly and mysteriously on the 10th June 323 BC.

The “Porus Medallions” or “Franks Medallion” (named after the donor of the first example of the coin to the British Museum) was discovered in modern Afghanistan in the late 19th century. The obverse shows a cavalryman, identified as a Macedonian by his Phrygian-style helmet and characteristic long lance (or sarissa), charging at an elephant with two warriors mounted on its back. The reverse shows another Macedonian horseman, or possibly the same one, this time standing and being crowned by a winged Victory but still wearing his distinctive helmet. However this Macedonian is carrying what could either be a sarissa or a royal sceptre in his left hand, and more importantly in his right hand he holds the thunderbolt of Zeus. The coin is obviously a reference to the Macedonian victory at the Hydaspes and it is just as clear that the Macedonian figure is intended to be Alexander himself, both through his wielding of the thunderbolt of his ancestor Zeus and through the distinctive white plumage which Plutarch tells us the king wore on either side of his helmet. The standing figure mounted on the elephant and brandishing a spear on the obverse has been identified as Porus because of the figure’s height. Porus is described in almost all primary sources as extremely tall, sometimes as over 2.1 metres or 7 feet tall, and the height of the figure on the elephant would certainly tally with those measurements. On some examples of the medallion it is even possible to discern the foot of the rider behind the elephant about halfway up its leg, adding further emphasis to the prodigious height of the man.

The depictions of Alexander and Porus on the medallions are interesting, but it is the dating of the coin that makes it truly fascinating. It is almost impossible to tell exactly when the coin was minted due to the lack of any kind of legend. However the coin has been approximately dated to the very end of Alexander’s lifetime, minted in Babylon either shortly before or shortly after his death in 323 BC. If we take the date before Alexander’s death and accept that it is Alexander himself featured on the reverse, then this series of coins is remarkable. It would represent not only the sole surviving depiction of Alexander the Great produced in his lifetime, but would be the earliest known image of an identified living person on coins. This coinage provides not only an intriguing mystery for numismatists but could also provide remarkable insight into the mindset of Alexander and his views on his own divinity. They also demonstrate, through the use of an image of a living person as a type, the development of coin types as a form of propaganda which would continue to be used throughout history.

![]() This month’s coin was chosen by Nathan Murphy, a final year Ancient History and Classical Archaeology undergraduate. Nathan’s research interests include the social and economic function of coinage and the spread of money in the ancient world. His dissertation is focussing on the monetisation of the Roman countryside between the first and fourth centuries AD, looking at the levels of monetary use among rural populations in Roman Egypt, Syria and Britain.

This month’s coin was chosen by Nathan Murphy, a final year Ancient History and Classical Archaeology undergraduate. Nathan’s research interests include the social and economic function of coinage and the spread of money in the ancient world. His dissertation is focussing on the monetisation of the Roman countryside between the first and fourth centuries AD, looking at the levels of monetary use among rural populations in Roman Egypt, Syria and Britain.

(Coin image above reproduced courtesy of Baldwin's Auctions Ltd, New York Sale XXVII, 304).

July 18, 2013

A week at the museum: The British Museum’s Numismatics Summer School, 8th–12th July 2013

The department of Coins and Medals at the BM is easy to miss: beside an indiscrete steel door at the rear of the money gallery, there is a bell which, when pressed, announces your arrival to the sound of trumpets. Inquisitive tourists watch as you enter. Then, as the door is locked, you realise that you have stepped into a giant safe: every room is isolated, while security cameras inspect your movements from above. This is unsurprising, considering the amount of gold and silver which now lies within snatching distance. Any would-be burglar, however, should consider the following before he melts down his loot – a haul of ancient coinage is today worth much more than the sum of its parts.

The department of Coins and Medals at the BM is easy to miss: beside an indiscrete steel door at the rear of the money gallery, there is a bell which, when pressed, announces your arrival to the sound of trumpets. Inquisitive tourists watch as you enter. Then, as the door is locked, you realise that you have stepped into a giant safe: every room is isolated, while security cameras inspect your movements from above. This is unsurprising, considering the amount of gold and silver which now lies within snatching distance. Any would-be burglar, however, should consider the following before he melts down his loot – a haul of ancient coinage is today worth much more than the sum of its parts.

Despite this, the first lesson we learnt at the BM’s Numismatics Summer School was that, to those who first created our western coinage system, the quantity of precious metal was all that mattered – coins had intrinsic value and no more. So why bother with coinage in the first place? Why not continue to value goods in oxen or tripods; or in unworked ingots of silver or gold? Perhaps coins were convenient and facilitated trade; or maybe the local king wanted to promote his own standards: the jury is still out, despite the mass of research into these fundamental questions.

Yet, there is still plenty to be gleaned from the hard evidence. I was absorbed by the statistical analysis of coin hoards, and intrigued by the eye-watering, frustrating and (ultimately) rewarding discipline of die studies. The twin processes of discovery and coin conservation were also described – invaluable insight for any aspiring archaeologist. Numismatics has never been an overpopulated field, but this didn’t turn a week with the experts into one of dry academia. The numismatists at the BM are diverse in both personality and approach; they are all devoted to their subject. Their explanations, both clear and comprehensive, brought the coins in the museum to life.

Over the course of the week we handled gold coinage, silver coinage, bronze coinage and alloyed coinage; struck coinage, cast coinage and square coinage; early Greek and later Hellenistic coinage, Roman Republican, Roman Imperial and Roman provincial coinage, iron-age British coinage, ancient Persian coinage, and even a little Islamic coinage to boot. I have come away with skills I intend to apply as I further my classical studies, not to mention a set of atrocious coinage-related jokes… In this spirit, I can safely say that, with the BM’s department of Coins and Medals, if you’re in for a penny, you’re in for a pound.

by Joe Grimwade

Clare Rowan

Clare Rowan

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…