All 1 entries tagged Mussolini

No other Warwick Blogs use the tag Mussolini on entries | View entries tagged Mussolini at Technorati | There are no images tagged Mussolini on this blog

August 01, 2019

From divinity to the Duce: the many meanings of the Julian Star

|

|

Augustus, Caesaraugusta (possibly), Spain, denarius, 19-18 BC.

RIC 1 37b, pg.44 (British Museum, R.6067).

Obverse: CAESAR AVGVSTVS; head of Augustus, wearing oak-wreath, left.

Reverse: DIVVS IVLIVS; comet with eight rays and tail upwards.

|

During Julius Caesar’s memorial games in 44 BC, a great comet allegedly appeared. Pliny the Elder writing in the 1st century AD quoted Augustus describing the comet:

On the very days of my games a comet was visible for seven days in the northern part of the sky. It was rising about an hour before sunset, and was a bright star, visible from all lands.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History 2.94

Today this comet, mainly known as the Julian Star or Caesar’s Comet, is one of the most famous comets in classical antiquity, despite there being little contemporary evidence to support its existence (see Ramsey and Licht, 1997). The image of this comet and other solar imagery featured throughout Augustus’ rule during 27 BC- 14 AD. Indeed, by the time of the Flavians in the late 1st century AD, solar symbolism in general “had become part of the imperial cult”, such was its importance (Weinstock, 1971, 384). The comet was also so influential that the fascist Italian dictator (who ruled from 1919-1943) Benito Mussolini included this image on a stamp to commemorate Augustus. Why did this symbol become so important, and what made it so resonant that someone more than 2,000 years later would choose to use it?

Firstly, we should take into consideration the symbolism of the star in the years before Augustus. Julius Caesar, Augustus’ adoptive father, initially put stars on his coinage in the years before his death in 44 BC (e.g. RRC 480/5a). The symbol of a star or comet had both positive and negative connotations around this time, being able to symbolize amongst other things “the divine or deified ruler”, yet also portend evil (Weinstock 1971, 378, 371). Whilst still alive Caesar may have only wanted to signify his descent from Venus with the star on coinage, but after his death it took on a new meaning. The common people interpreted the comet of 44 BC as a sign that Caesar had been received in heaven, which then helped push the star symbol as confirmation of Caesar’s divinity (Pliny, Natural History 2.94). Augustus further built upon this symbolism when he added a star on top of a bust of Caesar in the forum to mark the comet, and dedicated a temple to the deified Caesar (Suetonius, the deified Julius 88).

By using this symbol in his own coinage, Augustus could also make subtle connections between his own reign, the comet, star imagery and the divinity of Caesar (Williams 2003, 7). The symbol is a prime example of Augustus’ technique of “carefully nuanced suggestiveness” which he so often used in his reign (Galinsky 1996, 312). By associating himself with a symbol that was tied to Caesar’s image, Augustus was asserting his familial connection, while allowing further associations with divinity to also exist.

|

|

Augustus, M. Sanquinius, Rome, denarius, 17 BC,

RIC 1 340, p.66, (British Museum, 2002,0102.4960).

Obverse: AVGVST DIVI F LVDOS SAE, herald, in long robe

and feathered helmet, standing left, holding winged caduceus in

right hand and round shield with six-pointed star, in left hand.

Reverse: M SA[NQVI]NIVS III VIR, head of deified Julius Caesar,

laureate, right; above, comet with four rays and a tail.

|

Further symbolism was associated with the comet during the Saecular Games of 17 BC, which celebrated the start of a new age. To commemorate the games, the moneyer M. Sanquinius issued a coin series again featuring a comet, but within the context of these games, with the name of them inscribed on the coin obverse (LVDOS SAE). This coin may have been intended to highlight the prophecy made by the Haruspex Vulcanius, who proclaimed the 44 BC comet to herald a new age (Weinstock, 1971 195). Thus perhaps as well as power and ancestry, the comet came to resonate as a symbol of Augustus’ “Golden Age” as a whole.

|

|

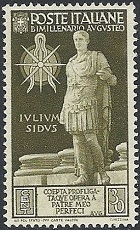

30 cent stamp with the

quote from Augustus’

Res Gestae.

|

By the 20th century, Augustus and his regime seem to have become a figure of world-renown; a 1937 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art called Augustus “one of the few statesmen who belong not to one country or to one continent but to the whole world” (Richter, 1938 272-273). Mussolini seemed to realise Augustus’ potential as a figurehead for fascism, as during the 1930s Augustus featured frequently in Italian propaganda. The bimillenium of Augustus’ birth was celebrated during 1937-8 and a stamp series commissioned in 1937, one of which featured the comet. Unlike Augustus’ coinage, which circulated within the bounds of an empire, these stamps were a possible means by which Italy as a newly fascist nation could broadcast its symbolism, both nationally and internationally (Reid, 1984 226). On this stamp this comet had come to represent Augustus as a whole with its position beside both a statue of Augustus and excerpt from his Res Gestae. The comet had transformed from a single phenomenon to a symbol synonymous with imperial power.

Primary Sources:

Pliny the Elder, Natural History volume I book II trans. H. Rackham (Harvard University Press: Cambridge, M.A. 1938)

Suetonius, Lives of the Caesars volume I: The deified Julius 88 trans. J. C. Rolfe (Harvard University Press: Cambridge, M.A. 1914).

Richter (1938) “The Exhibition of Augustan Art”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin Vol. 33, No. 12, pg. 257,272-279.

|

This month's coin of the month was written by Daisy Ashton. Daisy recently completed her BA in Ancient History and Classical Archaeology at the University of Warwick. She is interested in the ancient world's impact on modern heritage, and is going on to do an MPhil in Heritage Studies at the University of Cambridge.

Clare Rowan

Clare Rowan

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…