All 69 entries tagged Coin Of The Month

No other Warwick Blogs use the tag Coin Of The Month on entries | View entries tagged Coin Of The Month at Technorati | There are no images tagged Coin Of The Month on this blog

September 01, 2019

Achaean League Coinage and Collective Identity

On the Greek mainland in the Hellenistic Period, some of the city states united into federal leagues, the most successful of these being the Achaean League. In my undergraduate dissertation I wanted to show how the Achaean League developed its collective identity and how this affected the policy and the society of the League. Collective identity is how states and individuals can identify with both their home city and the overarching political body (i.e. a modern example is me saying I am both European and British). The coinage of the Achaean League acted as a means of spreading this message throughout the League. In this blogpost, I’m going to show how the coinage reflected the policy of collective identity. To examine this topic in depth I’m going to examine a coin from Megara and how the Megarians reconciled the ‘Dorian’ and ‘Achaean’ aspects of their identity.

Types of Achaean Coinage

|

Achaean Hemidrachm, minted at Sparta, with symbol of Dioscuri caps and abbreviation of LA on the reverse, and head of Zeus Homarius on the obverse.

Polybius proudly states that the Achaeans “formed the states into a community of allies and friends, but they have also adopted the same laws, weights and measures and coinage…” (Polybius, Histories, 2.37). This has been interpreted as a way of showing “the social and political solidarity of the second-century Peloponnese.” (Thonemann (2015) 72). These coins were silver hemidrachms, worth half a drachm, and were minted in nineteen different poleis of the Achaean League. Each of these cities produced the coins to a similar blueprint: a head of Zeus Homarius on the obverse, and a monogram of the word Achaean on the reverse. The different mints are indicated with either abbreviations or with symbols, such as the Pegasus of Corinth.

|

Achaean tetrachalkon, minted at Corinth, Obverse: Zeus with sceptre and holding Nike in his hand. Reverse: Seated figure of the personified Achaea. Both motifs were common throughout the Hellenistic World.

These ethnics and symbols helped to bind the cities to the league by associating them with the federal Achaean body and making them as one and the same, whilst celebrating the individual characters of the cities themselves; it shows dedication to the federal ideal. This is further proved by the bronze coinage of the league, which was struck in over forty-five out of the seventy odd cities in the league. These small poleis were committed to the league and were willing to invest heavily in that relationship. Warren suggests that over 1600 dies were used in the minting of these bronze coins, which is an extremely heavy investment, especially compared to how other poleis minted coins in the Hellenistic Period (Warren (2007); Thonemann (2015) 74).

Maintaining local identity in a federal state

|

Achaean Hemidrachm, minted at Megara. Obverse: Head of Zeus Homarius. Reverse: Achaean League monogram and abbreviation of word Dorian.

The collective identity of the Achaean League didn’t mean that various local identities were weakened. In fact, the network of poleis meant that they strengthened their local identities, and the environment of competition between the constituent members changed. Coinage was one media that expressed this.

This coin from Megara helps to show the nuance that went into how the ancient Greeks identified themselves. Across the Achaean monogram is the abbreviated ethnic, but rather than denoting the city of Megara, it draws attention to the Greek ethnic group of the Dorians. The Egyptologist Lynn Meskell has said that “identity is what is draped over a person by the groups of which he or she is part” ((1999) 32), indicating that identity is multi-faceted and complex, consisting of many layers. The complicated layers of this coin show that the people of Megara want to advertise their history as Dorians, and the political reality of their position as members of the Achaean League. One did not trump the other, and from the view of inter-polis competition, the historical baggage of the term will have had an effect on how Megara was received within the league.

Conclusion

This examination of Achaean coinage has shown how integrated the society of the Achaeans was, and that whilst Polybius’ assertion that the Peloponnese was a “single state” (2.37) is apt, the situation was a lot more complicated. Each member state had its own agenda and history, but worked under the umbrella of Achaean identity in order to be stronger and more efficient (Close (2018)). The coinage of the various states of the Peloponnese show how these states were able to reconcile the identities that both united them and showcased their uniqueness.

Bibliography

Primary

Polybius, Histories, trans. Waterfield, R. Oxford University Press: Oxford 2010.

Secondary

Close, E. “Megalopolis and the Achaean Koinon: Local Identity and the Federal State.” Teiresias 48.1 2018: 2–8.

Meskell, L. 1999. Archaeologies of Social Life. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Thonemann, P. 2015. The Hellenistic World: Using Coins as Sources. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Warren, J. 2007. The Bronze Coinage of the Achaion Koinon: the Currency of a Federal Ideal. London: Royal Numismatic Society.

|

This month’s entry was written by Jameson Minto, who recently graduated from Warwick. His dissertation was titled ‘The Achaean League and Collective Identity’ and dealt with the evolution of both the institutions of the league and the creation of the Achaean identity. Jameson runs his own blog, Musings of Clio, which discusses the ancient world, and he is set to study an MA in Classics and Ancient History at the University of Manchester.

August 01, 2019

From divinity to the Duce: the many meanings of the Julian Star

|

|

Augustus, Caesaraugusta (possibly), Spain, denarius, 19-18 BC.

RIC 1 37b, pg.44 (British Museum, R.6067).

Obverse: CAESAR AVGVSTVS; head of Augustus, wearing oak-wreath, left.

Reverse: DIVVS IVLIVS; comet with eight rays and tail upwards.

|

During Julius Caesar’s memorial games in 44 BC, a great comet allegedly appeared. Pliny the Elder writing in the 1st century AD quoted Augustus describing the comet:

On the very days of my games a comet was visible for seven days in the northern part of the sky. It was rising about an hour before sunset, and was a bright star, visible from all lands.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History 2.94

Today this comet, mainly known as the Julian Star or Caesar’s Comet, is one of the most famous comets in classical antiquity, despite there being little contemporary evidence to support its existence (see Ramsey and Licht, 1997). The image of this comet and other solar imagery featured throughout Augustus’ rule during 27 BC- 14 AD. Indeed, by the time of the Flavians in the late 1st century AD, solar symbolism in general “had become part of the imperial cult”, such was its importance (Weinstock, 1971, 384). The comet was also so influential that the fascist Italian dictator (who ruled from 1919-1943) Benito Mussolini included this image on a stamp to commemorate Augustus. Why did this symbol become so important, and what made it so resonant that someone more than 2,000 years later would choose to use it?

Firstly, we should take into consideration the symbolism of the star in the years before Augustus. Julius Caesar, Augustus’ adoptive father, initially put stars on his coinage in the years before his death in 44 BC (e.g. RRC 480/5a). The symbol of a star or comet had both positive and negative connotations around this time, being able to symbolize amongst other things “the divine or deified ruler”, yet also portend evil (Weinstock 1971, 378, 371). Whilst still alive Caesar may have only wanted to signify his descent from Venus with the star on coinage, but after his death it took on a new meaning. The common people interpreted the comet of 44 BC as a sign that Caesar had been received in heaven, which then helped push the star symbol as confirmation of Caesar’s divinity (Pliny, Natural History 2.94). Augustus further built upon this symbolism when he added a star on top of a bust of Caesar in the forum to mark the comet, and dedicated a temple to the deified Caesar (Suetonius, the deified Julius 88).

By using this symbol in his own coinage, Augustus could also make subtle connections between his own reign, the comet, star imagery and the divinity of Caesar (Williams 2003, 7). The symbol is a prime example of Augustus’ technique of “carefully nuanced suggestiveness” which he so often used in his reign (Galinsky 1996, 312). By associating himself with a symbol that was tied to Caesar’s image, Augustus was asserting his familial connection, while allowing further associations with divinity to also exist.

|

|

Augustus, M. Sanquinius, Rome, denarius, 17 BC,

RIC 1 340, p.66, (British Museum, 2002,0102.4960).

Obverse: AVGVST DIVI F LVDOS SAE, herald, in long robe

and feathered helmet, standing left, holding winged caduceus in

right hand and round shield with six-pointed star, in left hand.

Reverse: M SA[NQVI]NIVS III VIR, head of deified Julius Caesar,

laureate, right; above, comet with four rays and a tail.

|

Further symbolism was associated with the comet during the Saecular Games of 17 BC, which celebrated the start of a new age. To commemorate the games, the moneyer M. Sanquinius issued a coin series again featuring a comet, but within the context of these games, with the name of them inscribed on the coin obverse (LVDOS SAE). This coin may have been intended to highlight the prophecy made by the Haruspex Vulcanius, who proclaimed the 44 BC comet to herald a new age (Weinstock, 1971 195). Thus perhaps as well as power and ancestry, the comet came to resonate as a symbol of Augustus’ “Golden Age” as a whole.

|

|

30 cent stamp with the

quote from Augustus’

Res Gestae.

|

By the 20th century, Augustus and his regime seem to have become a figure of world-renown; a 1937 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art called Augustus “one of the few statesmen who belong not to one country or to one continent but to the whole world” (Richter, 1938 272-273). Mussolini seemed to realise Augustus’ potential as a figurehead for fascism, as during the 1930s Augustus featured frequently in Italian propaganda. The bimillenium of Augustus’ birth was celebrated during 1937-8 and a stamp series commissioned in 1937, one of which featured the comet. Unlike Augustus’ coinage, which circulated within the bounds of an empire, these stamps were a possible means by which Italy as a newly fascist nation could broadcast its symbolism, both nationally and internationally (Reid, 1984 226). On this stamp this comet had come to represent Augustus as a whole with its position beside both a statue of Augustus and excerpt from his Res Gestae. The comet had transformed from a single phenomenon to a symbol synonymous with imperial power.

Primary Sources:

Pliny the Elder, Natural History volume I book II trans. H. Rackham (Harvard University Press: Cambridge, M.A. 1938)

Suetonius, Lives of the Caesars volume I: The deified Julius 88 trans. J. C. Rolfe (Harvard University Press: Cambridge, M.A. 1914).

Richter (1938) “The Exhibition of Augustan Art”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin Vol. 33, No. 12, pg. 257,272-279.

|

This month's coin of the month was written by Daisy Ashton. Daisy recently completed her BA in Ancient History and Classical Archaeology at the University of Warwick. She is interested in the ancient world's impact on modern heritage, and is going on to do an MPhil in Heritage Studies at the University of Cambridge.

July 01, 2019

The 'man with the shovel' on the 'plomos monetiformes' of Baetica

A lead token from the 'series de las minas'.

Obverse: a naked man walking left, a shovel marked PRVM on his shoulder, holding out a bell. P S to either side; wreath border.

Reverse: Naked man standing right pouring water from an askos onto a beribboned phallus; broom below on exergual line, Q. CO ILLI Q around and LVSO in a tablet in the exergue; wreath border.

Stannard PC 25. American Numismatic Society, New York, Richard B. Witschonke Collection. Ex CNG 31, 9 September 1994, lot 1857 Casariego 1987, p. 26, no. 1, Carbone 2018 pl. 29 no. 3.

In Spain there exist large (45-50mm) struck lead monetiform pieces whose precise function remains elusive. Many of the pieces are decorated with the design shown on the specimen above: a naked man carrying a 'shovel'. Because of this image they were traditionally believed to be monetary pieces associated with mining in the region - the naked man was interpreted as a miner. But the figure looks very different to known representations of Roman miners, and Stannard has demonstrated that this figure (and other images) are actually shared between Baetica (Spain) and central Italy, appearing on monetiform objects in both regions. It is thus not a miner - but who is it? Stannard (1995) suggested the figure might be associated with agriculture (a farmer going off to work with a shovel, shown watering his plants on the other side) or with Italian theatre, since often the figure is shown with an overly large phallus.

|

|

Close up of the 'man carrying a shovel' inscribed with PRVM

or PRVNA and carrying a bell. (Stannard et al. 2017 fig. 25).

|

Many other pieces connected to this series show imagery related to the baths or the palaestra, and it perhaps in this context that we should seek clues as to the identity of our individual. As briefly mentioned by Stannard et al. (2017), the figure should likely be understood as a fornacator, the individual responsible for stoking the fires in the bath house to get the water warm. These individuals can be shown as naked and ithyphallic, as seen in the mosaic shown below. Our 'naked man with shovel' also holds a bell in his right hand, a variation only found in Baetica and not in Italy. This is likely a reference to the bell or gong that was rung by bath houses to announce that the water had reached the optimum temperature - so come take your bath now! This practice is referenced by several ancient authors and a bell was found in 1548 in the baths of Diocletian in Rome bearing the inscription FIRMI BALNEATORIS. A gong, uncovered in the Palaestra of the Stabian baths of Pompeii, probably served a similar function; bells might also be rung to indicate that the baths were soon closing and now was the last opportunity for a bath (Nielsen 1990, 111). If the fornacator was responsible for making sure the water was at the right temperature, then it would make sense that he is depicted with the bell that was rung when the temperature for bathing was perfect. Having identified the individual as a stoker of fires, we might return to the legend inscribed on the man's shovel: PRVM. I wonder if the legend might actually be PRVNA, the Latin term for glowing charcoal, with the N and A ligate (joined together). The figure on the other side of this lead piece, puring water from a vessel, may be a slave attending a master in the bath complex or bath attendant.

|

|

| Mosaic from Thamugadi showing a fornacator (stoker). (Nielson 1990) | Plomo monetiforme showing an ithyphallic man with shovel. Stannard PC no. 29 |

Are these pieces then bathing tokens? Stannard et al. 2017 argue they are not, since images related to bathing in this series are connected with other imagery that is not connected to the baths at all; some specimens also carry value marks, which suggests they had a monetary function. Lead tokens found in bath complexes in Italy, however, (e.g. in Fregellae and in Ostia), do not necessarily carry 'bathing' imagery; a wide variety of images may have been used in this particular sphere (just as mosaics in Roman bath houses are not all necessarily related to the activity of bathing). Those in Fregellae also appear to carry value marks. The alternative is that an image of a low-ranking bath worker should be chosen as an image for a pseudo-coinage, or a monetary series commemorating an act of euergetism related to the baths (as suggested by Stannard et al. 2017). This possibility is an intriguing one; hopefully future work will offer us further information in this regard!

This blog post was written by Clare Rowan as part of the Token Communities in the Ancient Mediterranean project.

Bibliography:

Carbone, L. (2018). The unpublished Iberian lead tokens in the Richard B. Witschonke collection at the American Numismatic Society. American Journal of Numismatics 30: 131-144.

Casariego, A., G. Cores and F. Pliego (1987). Catálogo de plomos monetiformes de la Hispania Antigua. Madrid.

García-Bellido, M. P. (1986). Nuevos documentos sobre minería y agricultura romanas en Hispania. Archivo español de arqueologia 59: 13-42.

Nielsen, I. (1990). Thermae et Balnea (2 vols). Aarhus, Aarhus University Press.

Spagnoli, E. (2017). Un nucleo di piombi 'monetiformi' da Ostia, Terme dei Cisiarii (II.II.3): problematiche interpretative e quadro di circolazione. Per un contributo di storia economica e di archeologia della produzione tra II e III secolo d.C. Annali dell'Instituto Italiano di Numismatica 63: 179-234.

Stannard, C. (1995). Iconographic parallels between the local coinages of central Italy and Baetica in the first century BC. Acta Numismàtica 25: 47-97.

Stannard, C., A. G. Sinner, N. Moncunill Martí and J. Ferrer i Jané (2017). A plomo monetiforme from the Iberian settlement of Cerro Lucena (Enguera, Valencia) with a north-eastern Iberian legend, and the Italo-baetican series. Journal of Archaeological Numismatics: 59-106.

June 01, 2019

Countermarks on Athenian Tokens

Athens is the city in the Classical world that minted tokens on a scale previously unparalleled, only to be superseded by Rome. Tokens in Athens had a continuous life of about seven centuries and facilitated numerous aspects of public life: the functioning of the Council, the Courts, the Assembly, participation in the Dionysia, the Panathenaea and the other festivals.

Researchers have commented on the relations between tokens and coins and have asked to what extent coins functioned as an archetype for tokens. The answer is clearly negative. Classical tokens do not resemble coins and functioned in an altogether different manner. They were probably used for the selection procedure of citizens who would fill offices and serve as public functionaries, and consecutively for the allotment of citizens to offices and even ‘workplaces’.

|

|

1.) Agora Museum IL1463.

Alpha with countermark of winged

caduceus, 31 mm.

|

Tokens with letters signify the allotment, the fact that citizens would be allotted randomly to offices (fig. 1). And here is a seeming similitude to coins: there exist letter tokens which are countermarked. But contrary to coins, where countermarking meant the revalidation of the item, so that issues were put afresh into circulation, the countermarking in this case signifies the particular sector of public life and complements the token design. Flans are particularly wide, probably because the placement of the countermark was conceived from the beginning. The designs of the countermarks – the winged caduceus (fig. 1), the kernos and the amphora in an ivy-wreath – are well attested in categories of official artefacts and they qualify as designs of the state seal (sphragis demosia). The exact offices they represent can only be conjectured but they can be seen as analogous to the stamps on the juror’s allotment plates; here the ‘owl in wreath’ stamp meant that the citizen was eligible for jury allotments and the ‘Gorgoneion’ stamp meant magisterial allotments.

It seems that the solution of the countermark was short-lived because only three out of the approximately three hundred Hellenistic tokens excavated in the Athenian Agora have a countermark placed next to a letter type.

Contrary to the rarity of countermarks on tokens dated to before Sulla’s sack of the city (86 BC), which practically marks the end of the city’s independence, countermarks are far more common in Athens of the Roman Imperial Period (fig. 2). In particular more than 200 specimens demonstrate at least one countermark out of the 620 tokens that can be securely dated to the period between the first century AD and AD 268, when the destruction inflicted on the city by the Herules marked the end of token use in Athens. It is worth noting that most of the tokens in strata and deposits containing Herulian debris carry countermarks. Our attention is particularly attracted by the countermarks of ‘snail and rabbit’ and ‘stork holding lizard by the tail’, which are the most abundantly attested. In the trench containing dumped fill as a result of clean-up operations after the Herulian sack, countermarked tokens co-exist with un-countermarked specimens, albeit they are found on the same types. These mainly celebrate the cults of Asklepios, Hygieia and Telesphoros (fig. 3) or Asklepios alone, Dionysos (fig. 4), Serapis, Zeus and Nike, Athena and Nike and also Themistocles, and the Minotaur, alone or with Theseus. The latter cases may be related to the claims of Athenian elite families for status and prestigious ancestry.

|

|

2.) Selection of tokens excavated in and around the Attalos Stoa,

Athenian Agora (Archives of the American School of Classical

Studies 2012.25.0091).

|

|

|

The same pattern is also encountered on the tokens found in piles on the floors of the Attalos Stoa and also in the immediate vicinity of the Attalos Stoa to the south.

|

Specimens are also quite often found to have been countermarked twice by the same stamp, such as the token with an Athena bust and two countermarks of the snail and rabbit type (fig. 5). More puzzling are the Herakles and tripod tokens, which on their reverse side bear three distinct countermarks: stork and lizard, snail and rabbit, and a third design not easily identifiable (fig. 6).

Both the designs of stork and lizard and of snail and rabbit relate to universal symbols and refer to narratives that could be easily adapted as badges and emblems. The stork in particular was very popular in medieval heraldry.

The meaning of the countermarks is not easy to decode. The countermarked tokens capture only a moment in the history of Athens, because they represent the types and specimens that were in circulation at the time of the Herulian Invasion and their preservation may be thought random. Even the hoarding of countermarked pieces together with un-countermarked specimens may have been occasioned by the circumstances that prevailed shortly after the destruction. The interpretation of the countermarks is all the more hindered by the scarcity of tokens in the centuries from the Augustan Period to the mid-third century AD, which could serve as a point of comparison.

Margaret Crosby suggested that the same countermark on varying types might help to identify the same authority behind the issuing of the tokens. The purpose of these tokens would have been admissions to games and festivals, such as those referred to in inscriptions of the third century AD. In fact the legend on two of the types reads ‘of the Gerusia’, the council formed by notable Athenians and instituted by the emperor Commodus in the year AD 178/9, which had the agonothesia of festivals. The Attalos Stoa was thought to provide an advantageous view of spectacles and processions going along the Panathenaic Way and in view of this function, tokens excavated there seem to come as no surprise.

It is well known that the holding of offices in the Hellenistic and increasingly in the Imperial period involved considerable private expense. The iconography of the countermarks and even some of the token types might then be related to wealthy gerusiastai and office-holders in general, who competed for the recognition of the people, an idea already advocated by Margaret Crosby.

|

Along these lines, the countermarking a second or even a third time of tickets is to be considered as a renewal of their otherwise short lifetime. Roman period tokens were literary ‘time stamped’ and given out for a second or a third use since all the festivals were naturally recurring events. The registration of singular events constitutes the very essence of tokens across time, not unlike the modern-day block chain and its digital database or ledger.

This month's entry was written by Mairi Gkikaki. This blog forms part of the Project 'Tokens and their Cultural Biography in Athens from the Classical Age to the End of Antiquity', a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Action, which has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 794080-2.

Bibliography:

W. Bubelis, ‘Tokens and imitation in ancient Athens’, Marburger Beiträge zur Antiken Handels-, Wirtschafts-, und Sozialgeschichte 28 (2010), 171-195.

E. Curtius, Über Wappenstil und Wappengebrauch im klassischen Altertum (Berlin, 1874).

M. Crosby, ‘Lead and Clay Tokens’, in M. Lang and M. Crosby, Weights, Measures and Tokens. The Athenian Agora, vol. 10 (Princeton, 1964), 69-146.

D.J. Gaegan, The Athenian Constitution after Sulla, Hesperia Supplements 12 (Princeton, 1967).

M. Gkikaki, 'Tokens in the Athenian Agora in the Third Century AD: Adverstising Prestige and Civic Identity in Roman Athens', in A. Crisà, M. Gkikaki, and C. Rowan, Tokens: Cultures, Connections, Communities (London: Royal Numismatic Society, forthcoming)

S. Killen, Parasema. Offizielle Symbole griechischer Poleis und Bundesstaaten (Wiesbaden, 2017).

J.H. Kroll, Athenian Bronze Allotment Plates (Cambridge, 1972).

J.H. Kroll, ‘The Athenian imperials: results of recent study’, in J. Nollé, B. Overbeck and P. Weiss (eds), Internationales Kolloquium zur Kaiserzeitlichen Münzprägung Kleinasiens. 27-30 April 1994 in der Staatlichen Münzsammlung (München, 1997). 61-9.

M. Lang, ‘Allotment by tokens’, Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte 8, 1959, 80-9.

B. Maurer, ‘The Politics of Token Economics’, in. A. Crisà, M. Gkikaki, and C. Rowan, Tokens: Cultures, Connections, Communities (London: Royal Numismatic Society, forthcoming).

K.D. Mylonas, ‘Αττικά Μολύβδινα Σύμβολα’, ArchEph 40, 1901, 119-22.

J.H. Oliver, The Sacred Gerusia. The American Excavations in the Athenian Agora. Hesperia Suppl. 6 (Princeton, 1941).

P.J. Rhodes, A Commentary on the Aristotelian Athenaion Politeia (Oxford, 1981).

G.C. Rothery, Concise Encyclopedia of Heraldry (London ,1994, reprint of the book first published in 1914).

H.A. Thompson and R.E. Wycherley, The Agora of Athens: The History, Shape and Uses of an Ancient City Centre, The Agora of Athens, volume 14 (Princeton, 1972).

P. Tselekas, ‘Countermarks on the Hellenistic Coinages of Lesbos’, in P. Tselekas (ed), Coins in the Aegean Islands. Proceedings of the Fifth Scientific Meeting 16-19 September 2010, (Athens, 2010), 127-153

O. Van Nijf and R. Alston (eds), Political Culture in the Greek City after the Classical Age (Leuven, 2011)

May 01, 2019

Greek by name, Indian by nature: Indo–Greek Coinage

|

|

Bactria: Agathocles. 180-165 BCE. Copper alloy. BMC 1844,0909.61

Obverse: Brahmi legend. Female deity.

Reverse: Greek legend. Maneless lion.

|

If I told you this was a Greek coin would you believe it? The writing on the obverse is decisively not Greek; the square shape is certainly not what we are used to in Greek coinage, and the female deity on the obverse doesn’t look like anybody in the Greek Pantheon. The only clue we get to this coin’s ‘Greek’ origin is the Greek legend on the reverse, which reads ‘BAΣIΛEΩΣ AΓAΘOKΛEOYΣ’, translated as ‘King Agathocles’. It is an Indo-Greek coin, minted in this way for a very specific political purpose: to try and assimilate the Greek king with his Indian subjects.

To understand how a coin like this can be produced, we must start by understanding its geo-political context. It was minted in Bactria (the area that comprises modern day Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Northern Pakistan and Uzbekistan) in the 2nd century BCE by the Indo-Greek king Agathocles. Bactria, by the 2nd century, had already established itself as a real mixing pot of Greek, Afghan, and Indian culture. The region was first exposed to Greek culture after Alexander the Great conquered the territory in the 320’s BCE. Then Seleucus I (a Greek successor to Alexander, one of the Diadochi) established himself as ruler in Asia and his dynasty retained power for another century, further reinforcing the Greek influence in the area. Bactria gained independence between 250-240 BCE, and the Greek Diodotus I became the first Greco-Bactrian king. In the 180’s Greco-Bactrian kings, notably Demetrius I and Menander, started to conquer parts of northern India. Consequently, scholars refer to the kings who ruled this new territory, comprising parts of India, as the Indo-Greek kings. It was in this context that Agathocles, the king who minted the coin in discussion, was operating.

Almost every aspect of this “unusual” coin serves Agathocles’ political purpose. “Unusual” is in inverted commas, as, in fact, Agathocles was following an extremely common trend. It just wasn’t a Greek trend. The kings of the Indian Mauryan dynasty who ruled from the 4th to the 2nd centuries BCE minted almost exclusively square coins. The script on the coin is called Brahmi, the script in which the local Indian language, Pakrit, was written. The legend reads ‘King Agathocles’ in Brahmi script (Rajane Agathuklayasa). Not only was Pakrit the language of the locals, it was also the language of Buddhism, and Agathocles put this script on his coinage to show a genuine attempt at assimilation of Greek and Indian culture.

The images on both sides of the coin also evoke Indian culture. The female deity on the obverse is believed to be Subhadra, the sister of Krishna. The animal on the reverse is agreed to be a ‘maneless lion’, and refers to the literal meaning of Agathocles’ brother’s name: Pantaleon. It was Mauryan custom to use symbols or images to refer to oneself, rather than simply put a portrait on the coins as the Greeks usually did, again, part of Agathocles’ agenda to blur the lines between Greek and Indian culture.

Coins such as these cause us to pause and think: what does ‘Greek’ mean? Does it mean the presence of the Greek language? Minted by a Greek? Because this coin certainly has those aspects. However, this coin would stick out like a sore thumb in a collection of ‘traditionally Greek’ coins. It reveals that in this part of the world, the definitions between Greek and Indian are not so clearly cut. Would an Indian local see this as a Greek imitation of something they had been used to, or would they see it and think there is nothing out of the ordinary, apart from a few (Greek) letters they didn’t understand? These are questions that I am unable to answer here, but that are important to consider when drawing the boundaries between ‘Greek’ and ‘non-Greek’.

|

This month’s entry was written by Tunrayo Olaoshun, a 4th year undergraduate of Ancient History. She developed a further interest in numismatics during her year abroad in Bologna. Her main interests lie in the later Roman Empire.

Select bibliography:

Avari, B. (2016). India: the ancient past: a history of the Indian subcontinent from c. 7000 BCE to CE 1200. (London, New York: Routledge)

Narain, A. (1989). The Greeks of Bactria and India. In A. Astin, F. Walbank, M. Frederiksen, & R. Ogilvie (Eds.), The Cambridge Ancient History. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Tarn, W. W. (2010) The Greeks in Bactria and India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (Cambridge Library Collection - Classics).

April 01, 2019

The snake–god and the satirist

|

|

This bronze coin from Abonuteichos, on the southern coast of the Black Sea, depicts the snake-god Glycon on the reverse. The serpent is depicted curled up, but with its head raised, and with long hair. It is labelled as ‘ΓΛΥΚΩΝ ΙΩΝΟΠΟΛΕΙΤΩΝ’ (Glycon of the Ionopolitans).

It was minted during the dual reign of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus (AD 161-69). The latter is depicted on the obverse wearing a laurel, along with the legend ‘AVT KAC (sic) Λ ΑΥΡΗ οΥΗΡοC’ (Imperator Caesar L. Aurelius Verus).

This coin is especially interesting as a result of a treatise penned by the second century AD satirist Lucian. Alexander the False Prophet details how the titular Alexander (born c. AD 105-115) managed to con locals and outsiders alike into handing over their money in return for prophecies from Glycon, whose cult he founded. The survival of Lucian’s treatise gives us a fantastic opportunity to tie together material and literary evidence on the cult.

The first thing to notice on this coin is the long, thick hair of the snake, which is somewhat anthropomorphic. Lucian explains that even though the snake was living, a new head was crafted out of linen by Alexander and a colleague before the cult began:

they had long ago prepared and fitted up a serpent’s head of linen, which had something of a human look, was all painted up, and appeared very lifelike. It would open and close its mouth by means of horsehairs, and a forked black tongue like a snake’s, also controlled by horsehairs, would dart out.

Lucian, Alexander 12

Lucian explains how once this stage was complete, Alexander buried tablets prophesying that Asclepius would take up residence in Abonuteichos, which provoked people to build a temple (Lucian, Alexander 10). He then ran around in a frenzy, before ‘discovering’ a goose-egg, from which a baby snake emerged (Lucian, Alexander 13-14).

When the cult opened soon after, people apparently assumed that Glycon, the full-size snake-god shown on this coin, had grown out of this tiny snake within a few days (Lucian, Alexander 16). Lucian claims that when Glycon was being displayed at this grand opening, Alexander concealed its real head under his arm, showing only the linen head to the people (Lucian, Alexander 15). This is in contrast to the depiction on the coin, in which the anthropomorphic head is shown as a part of the snake’s body.

The cult then began offering predictions and oracles for anyone able to pay, and there were plenty of visitors, whom Lucian characterises as ‘thick-witted’ (Lucian, Alexander 17). Alexander would ask them to hand in their requests on scrolls, which he would unroll and secretly reseal, and pretend that the answer he gave them came from Glycon (Lucian, Alexander 19-20). He even purported to make Glycon’s (linen) head speak, thanks to an attendant using a horsehair mechanism and a tube (Lucian, Alexander 26).

Lucian’s account also broadly ties up with other evidence suggested by this coin. For example, the satirist writes that once Alexander gained fame, even in Rome, due to the rapid spread of the cult, he requested that a coin be produced with an image of himself on one side, and Glycon on the other (Lucian, Alexander 58). While we have never found any coins which depict Alexander himself (Jones (1986) 146), this coin shows that half of his desire was granted, at any rate.

According to Lucian, Alexander also requested that the Emperor change the name of his city from Abonuteichos to Ionopolis (Lucian, Alexander 58). Petsalis-Diomidis argues that this was a more prestigious name, relating to the mythical ancestor of the Ionians, Ion. This emphasis on Greek identity was perhaps enhanced by the success of the cult (Petsalis-Diomidis (2010) 31). Our coin does indeed display the name of Ionopolis. However, we need not assume that the rise of the cult and the name change came in parallel. This is because an earlier Glycon coin, minted under Antoninus Pius, uses the name Abonuteichos instead of Ionopolis, so the change must have been a gradual one (RPC IV 5359).

Some Epicureans, and even Lucian himself, attempted to expose the cult’s fraudulence. Alexander attempted to whip up the crowd to stone one such detractor (Lucian, Alexander 44-45), and Lucian himself claims to have been almost killed (Lucian, Alexander 56). Despite these efforts, however, the cult seemed to stay strong long after Lucian, because Glycon remained a popular image on Abonuteichos’s coinage from as late as the reign of Trebonianus Gallus in the mid-third century (RPC IX 1218).

Jones rightly suggests that we should take Lucian’s account with a pinch of salt. He argues that it is heavily biased, and contains many common tropes of invective literature, and that the question of fraudulence seems unanswerable or perhaps beside the point (Jones (1986) 134, 136, 146, 148). Nonetheless, literary and material evidence do provide a broadly unified picture for the fame, the influence and the imagery of the cult of Glycon.

|

This month's entry was writte by Matthew Smith. Matthew is an MA by Research student at the University of Warwick. He is especially interested in Greek authors of the second century AD. His research focuses on the role which divine dreams from Asclepius played in medicine during this period, looking in particular at Galen and Aelius Aristides

Sources:

Petsalis-Diomidis, A. (2010) Truly Beyond Wonders: Aelius Aristides and the cult of Asklepios (Oxford University Press: Oxford)

Jones, C.P. (1986) Culture and Society in Lucian (Harvard University Press: Cambridge, M.A.)

Lucian, ‘Alexander the False Prophet’, in Lucian Volume IV, trans. A.M. Harmon (Harvard University Press: Cambridge, M.A. 1925)

March 01, 2019

MORA! A Roman token showing a game

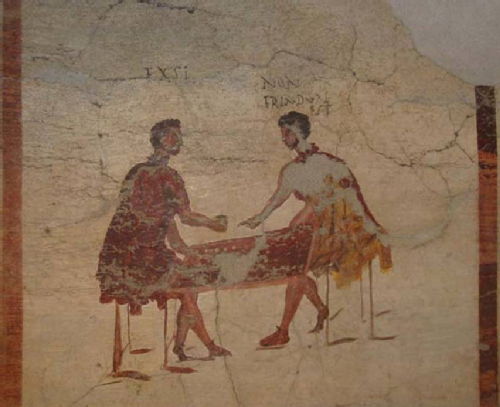

Bronze token from the Julio-Claudian period. On one side two boys are shown seated facing each other, a tablet on their knees, playing a game. The boy on the right has a raised right hand. At the left is a cupboard or doorway (?); MORA above. On the other side is the legend AVG within a wreath. (From Inasta Auction 34, 24 April 2010, lot 381, Cohen VIII p. 266 no. 6, variant).

This token is part of a larger series of monetiform objects which are characterised by Latin numbers on the reverse. Some examples, like that shown here, have the legend AVG (referring to the emperor, Augustus) instead of a number. This same imagery, of two boys playing a game, is also found on a token with the number 6 (VI) on the other side; another example has the number 13 (XIII) on the reverse (Paris, Bibliothèque national no. 17088). This token series carry portraits of Julio-Claudian emperors or deities, or playful scenes, including imagery of different sexual positions (a sub category of tokens called ‘spintriae’ today).

|

|

We know this token is connected to the broader series from the Julio-Claudian period because of another specimen, now in the Ashmolean museum (Ashmolean Museum, Heberden Coin Room, photo no. 10544; shown left). This token carries the same design (AVG within a wreath) as the token above, and in fact the same die was used for both tokens (called a die link).

But what of the scene on the other side? Two men or youths sit opposite each other with a gaming board between them; the figure on the right raises his hand and there is a doorway behind the figure on the left. The word MORA sits above the scene: in Latin mora meant a pause or delay; it might also be used in a more imperative sense: wait! The word moraris is found on rectangular bone pieces whose function is also unknown but are thought to be gaming pieces (tesserae lusoriae). We thus have a scene of game play involving two individuals at a moment in time when one player is being asked to pause.

The scene is reminiscent of a painting from the bar of Salvius in Pompeii in which two men are depicted playing dice with their speech written above them - one declares 'I won' (exsi), while the other protests 'It's not three; it's two' (non tria duas est). Other paintings show the quarrel escalating, with the landlord eventually throwing the two individuals out of the bar.

|

The gaming scene on this token, as well as the numbers present on most of the tokens of this broader series, has led to the suggestion that these pieces functioned as gaming counters. However, unlike the bone gaming counters that carry numbers, these pieces have never been found together as a ‘set’, and don’t carry scratches that suggest they might have been used on a board (though this does not exclude their use in lotteries or similar). Instead it is possible that the scene was chosen because it communicates a feeling of fun. Lead tokens also carry numbers and similar scenes (including a scene of game play on a lead token said to be found in Ostia); these objects may have been used in festivals or other contexts associated with game play.

This blog entry was written by Clare Rowan as part of the Token Communities in the Ancient Mediterranean Project. It is based on a catalogue entry for a token that will feature in a forthcoming exhibition on ancient games and gaming in Lyon in June 2019, which is part of the Locus Ludi project.

Related Bibliography

Mowat, R. (1913). Inscriptions exclamatives sur les tessères et monnaies romaine. Revue Numismatique 67: 46-60.

Rodríguez Martín, F. G. (2016). Tesserae Lusoriae en Hispania. Zephryus 77: 207-20.

Rostovtsew, M. (1905). Interprétation des tessères en os avec figures, chiffres et légendes. Revue Archéologique 5: 110-24.

February 01, 2019

Honours, Health and Hairstyles

Dupondius of Tiberius, Rome, AD 22-23. RIC I2 Tiberius 47, British Museum No. R.6361. Image reproduced courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.

This Roman copper alloy coin was produced in 22-23 AD, in the middle of Tiberius’ reign, and is held by the British Museum, but is not currently on display.

It is part of a series depicting a draped female bust, with the legend “SALVS AVGVSTA” on the obverse, while the reverse carries the abbreviation “S C”, signifying the coin was struck by a decree of the Senate, and the legend “TI.CAESAR.DIVI.AVG.F.AVG.P.M.TR.POT. XXIII”.

The obverse is understood to be a portrait of Livia Drusilla, wife of Augustus and Tiberius’ mother, who died in 29 AD, aged 86. While Livia was honoured with statues and portrait busts in her lifetime, there are no explicitly identifiable representations of her on contemporary imperial coins. Instead, depictions which may represent her on Roman imperial coins are ambiguous, carrying attributes which are identifiable with Ceres, or Pax – both of which are associated with Livia in various inscriptions, statues and possibly on the Ara Pacis. However, coins from provincial mints, particularly Greek and Egyptian, carry portraits with legends which do name her. This may partially be due to Augustus being cautious of imagery in Rome which could be construed as reflecting suggestions of monarchical ambitions. Although the idea of monarchy was abhorrent in Roman culture, it was much more acceptable and less contentious in societies in the eastern Mediterranean, which may explain why Livia was clearly portrayed there. Additionally, Marcus Antonius had featured women (Fulvia, Octavia and Cleopatra) on his coinage, and Augustus may have wished to both distance and differentiate himself from this for a variety of reasons (see August 2018 blog entry which discusses Fulvia).

Despite this, Augustus (then Octavian) had, in 35 BC, granted both Livia and his sister Octavia unprecedented honours: public protection comparable to that provided for tribunes; the right to manage their own estates without a guardian; and the right to honorific statues (see Cassius Dio, Roman History, 49.38.1). Honouring both Livia and Octavia thus had an underlying political motivation – by elevating them as paradigms of Roman matronly behaviour, Augustus obliquely, but publicly, reproached Marcus Antonius, who was living openly with Cleopatra in Egypt and mistreating Octavia, who he had married in 40 BC in an attempt to cement relations between himself and Octavian.

With the death and deification of Augustus in 14 AD, Livia had been adopted into the Julian family and was known as Julia Augusta, however the “Augusta” on the dupondius’ legend is not her name, but an adjective relating to “salus”. Tiberius gave his mother further honours, but vetoed attempts by the Senate to grant more titles to Livia – in this he followed Augustus’ lead, as he had granted Livia no official titles in his lifetime, again perhaps to avoid suggestions of monarchical ambitions. However, despite this, Livia was popularly, but unofficially, designated mater patriae (mother of her country).

In 22 AD, Livia had been seriously ill, and in view of her advancing years, her recovery was considered remarkable, and resulted in the Equestrian order dedicating a statue to Equestrian Fortune at Antium (see Tacitus Annals 3.71). The coin’s obverse legend “Salus Augusta”, is not a direct reference to this illness or recovery, although it may be understood to allude to it. Comparatively, Augustan coins from 16 BC commemorate vows for Augustus’ salus (health/safety), but on these the legend is clear “Salus Augusti”, with the genitive case clearly evidencing the salus belonged to Augustus. Instead, in this case, it is understood as being a reference to the good health of the state, and there may also be a politically-charged reference to this being dependent on Livia’s well-being.

Looking more closely at the portrait on the coin, Livia’s coiffure is arguably the most striking element. Parallel waves on the crown of her head from a central parting, connect to fuller waves across her forehead, becoming rolled braids which run from her temples to wrap the chignon, which sits at the back of her neck. Absent from this coiffure is the nodus - a wide knot of hair rolled forward to sit above the forehead.This was a defining characteristic in Livia’s portraiture in statuary prior to 14 AD.

This later hairstyle was softer and although the portrait may hint at Livia’s maturity via the fuller cheeks and perhaps the suggestion of a double chin, the overall impression is of idealised youthful Roman beauty – large eyes, an aquiline nose and strong mouth. At least four sculptural marble heads, which all date to the reign of Tiberius, match closely the coiffure shown on the Salus Augusta dupondii series, suggesting that this particular representation of Livia, not dissimilar to her coiffure on the Ara Pacis, had become more widely disseminated, although it is worth noting that the nodus portrait type of Livia was not replaced by this and continued to be used.

|

This month's coin was written by Jacqui Butler. Jacqui has just completed the first year of the MA in Ancient Visual and Material Culture (part time), having gained a BA in Classical Studies with the Open University last year. Her main interests lie in the visual depictions of both mythical and real women in Roman material culture, specifically in art, but also their representation in epigraphy on funerary monuments.

Bibliography

Barratt, A.A. (2002) Livia: First Lady of Imperial Rome, Yale University Press.

Bartman, E. (1999) Portraits of Livia, Cambridge University Press.

Wood, S.E. (2001) Imperial Women, A Study in Public Images, 40 BC – AD68 (Mnemosyne, bibliotheca classica Batava, Supplementum 195).

December 01, 2018

An Unusual Victory Coin

RIC II Trajan 557. Image reproduced courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.

The practice of issuing a victory coin after the conquest of a new territory was frequent in ancient Rome and it was a practice with a long tradition. In most instances what is depicted on the coins is either a scene in which a representation of the defeated country is mourning (cf. Iudeea capta, RIC II, Part 1 (second edition) Vespasian 161), or a symbol of the defeated country (cf. Aegypto capta, RIC I (second edition) Augustus 275A). However, one of the coins issued by Trajan after the conquest of Dacia is very different.

This coin is a sestertius dated between AD 103 and AD 111, issued in Rome, and now kept in the British Museum. On the obverse of the coin we find the bust of Trajan, laureate, facing right, with the text ‘IMP CAES NERVAE TRAIANO AVG GER DAC P M TR P COS V P P’- Trajan’s name and titles in the dative. On the reverse is a combat scene in which the river Tiber pushes Dacia to the ground with his right knee. The violence and the dynamism of this image is unusual for a Roman coin and I will present my hypothesis for this matter in this article.

This coin was issued to celebrate the Trajan’s victories over the Dacians. In AD 101, Trajan crossed the Danube and attacked Dacia despide the treaty that his predecesor Domitian had made with the Dacians. Another war followed in AD 106 after which most of Dacia became a Roman province.

The exact causes are controversial because of the lack of contemporary sources, but Dio’s text suggests that it was a punitive war. Regardless if this is true or not, it is clear that Trajan wanted to display this image and maybe show through this image that the nations willing to attack Rome would be defeated in battle.

The fact that it is the personification of the Tiber, a river, that is shown defeating Dacia is very interesting. On Trajan’s column, which depicts his wars against the Dacians, there is another personification of a river: the Danube. As the coin circulated over time, a viewer who had seen the column once it was completed in AD 113 might recall its scenery and the battle scenes depicted upon the monument. On the column the Danube is represented helping the Roman army.

This was the first Roman conquest in fifty years and it is possible that Trajan wanted to show it in a memorable way. To do this he chose to use this vivid violent scene to impress the people who would see it and to suggest that more territories would be conquered: in 114 and 115 he would also annex Armenia.

So, I think that the fact that Trajan wanted to show the people what happened if a people were to challenge Rome may have contributed to the creation of this unusual victory coin.

|

This month's entry was written by Luiza Diaconescu, a third year undergraduate student in Classical Civilisation. Luiza is very interested in Roman history and literature.

Select Bibliography:

Bellinger, A & Berlincourt, M (1962) ‘Victory as a coin type’, Numismatic Notes and Monographs 149:1-68

Bennett, J. (2001) Trajan: Optimus Princeps (Bloomington: Indiana University Press)

November 01, 2018

Fantasy Coins

This coin looks like a Roman coin. It is circular, it bears the head of the emperor, in this case Nero, and the legend (the writing on the coin) appears around the head. It is made of copper rather than the mixed-alloy bronze that was common in the Roman imperial period. However, the intent of the maker is to make a low value denomination. The lettering S C on the reverse (tails side) is a common feature for Roman issues in bronze, and the appearance of monuments, like the Ara Pacis in this case, is well attested. However, this is not a Roman coin, nor is it a modern imitation. This is a Fantasy coin; a coin reflecting the currency of a fantasy or an alternative history world.

Fantasy coins are produced by a number of different modern companies in response to the explosion of interest in fantasy games, such as Dungeon and Dragons. The coins can reflect specific worlds, such as Westoros (the world of Games of Thrones) or ancient Rome. Other ranges relate to generic fantasy worlds, particularly a specific racial or cultural group in that world. Elvish, dwarvern, barbarian, dragon and orcish communities are among the many catered for. Futuristic coins, representing the coins of imagined galactic empires, are also produced. In order to relate the coin to the subject matter, the images on the coin and more occasionally its shape are utilised. Such images are based on popular tropes related to the fantasy race. Dwarvern coinage for instance tend to show anvils, hammers and bear Nordic runes, ultimately derived from a Norse description of dwarfish smiths in the Prose Edda, a medieval text detailing Scandinavian myths. Orc coins often bear weapons or warriors, reflecting the original inspiration of orcs from Tolkien as creatures obsessed with war.

In many cases, a specific range of Fantasy coins is not tied to a particular game. The generic imagery is used so that the pieces can be accommodated in a number of different settings, allowing for a wider array of customers. The general audience of these coins are gamers and curiosity collectors, though these are often not separate groups. Players of “roleplaying” games, in which the players control characters in an imagined setting, with one player known by various names (Game Master, Dungeon Master or Keeper among many others) guiding the story. In these contexts, props are often utilised. These primarily consist of miniature figures representing the characters and their opponents, but increasingly other props are utilised to increase the immersion in the game. This is particularly evident in the real-world equivalent of role-playing, larping (otherwise known as live-action roleplaying) in which the participants physically portray their characters through costume and acting. Props are particularly valued in such settings, and the organisers of these events often produce their own coins. There are even events where complex denomination systems accompany the coins. For these groups, the coins are often bought in bulk. However, individual coins are also available for purchase. These would not be suited to games that require many coins, so these coins have a premium on their artistic value. As a result, Fantasy coins tend to be larger than most modern coins, and they often bear high quality designs. The Ancient Greeks also produced large coins with high quality images, so the use of coins as aesthetic pieces marks a continuation of an ancient tradition.

One would think that the coins would be highly unusual, as they are products of imagination. However, most fantasy coins are almost identical to the coins produced in the ancient period. The majority of fantasy coins are depicted as round objects, with an image on each side. Most ranges of fantasy coins have three separate denominations, with a gold, silver and copper issue. The only differences are the subject matter of images upon the coins and that they are not usually made of precious metal (like gold or silver), unlike the ancient coins which were intrinsically valuable in their own right. Since coinage began in 7th century BC Turkey, coins in the western world have retained the same features. Even Bitcoin is represented as a circular object, despite its digital form itself having no physical shape. Fantasy coins, for all the imagination behind them, are slaves to the trope. There are a few attempts to get away from round coinage for particularly exotic cultures, with some coins represented as moons, axe heads or as hexagons. In most cases, however, the producers of these coins are bound to their customers’ understanding of what a coin should look like.

Returning to our Fantasy Coin example, the coin copies a Roman issue in terms of its iconography (e,g, RIC 1 527). It is not, however, an imitation. The size of the original Roman denomination, an as, is not copied. As with other fantasy coins, the Nero coin is part of a series of gold, silver and copper coins, classed under the title “Roman”. As the smallest denomination, the coin is the smallest size in the series, whereas the gold coin is the largest coin of the set. In the ancient world, the size difference in coins was usually unnecessary; gold coins were intrinsically more valuable due to their metal content, so even the smallest gold coin was more valuable than the largest bronze coin and bronze coins were generally larger in antiquity. However, for modern Fantasy coins it would seem that bigger is better, so the highest denomination is afforded the largest size, and thus the greatest prestige. Within the series is a silver coin depicting a Constantine issue, and a gold coin bearing the Republican head of Roma, the titular goddess of Rome, with Jupiter riding a chariot alongside Victory on the reverse. The latter image was prominently featured on silver coins struck during the Roman Republic; the placement of the image on a gold coin here indicates that the modern manufacturer saw this image as worthy of a higher value.

|

|

|

Historical accuracy is not the intention behind these coins. What matters is the modern audience’s perception of what a coin is and what Roman culture was. Hence the more valuable coins are larger and the images chosen are ones that reflect “Roman-ness”. Hence emperors, monuments and famous gods are preferred over other images, like the many personifications of lesser deities that decorate the majority of ancient Roman coins. However, the manufacturers have chosen to imitate Roman coins rather than create their own images, so there is a modern desire for “authenticity” in some sense that the producers of these pieces are accommodating. This is not always the case; Fantasy Spartan coins exist, yet in reality the Spartans had no coins. As a result, standard pieces of Greek military equipment, like the Corinthian style helmet, are utilised for the iconography of these pieces.

The expansion in the Fantasy coin trade represents a continuation of coins as an art form. From their beginnings, coins in Europe bore high quality designs. The Rennes Patera show that certain individuals collected coins and valued them for the iconography upon them. There is little difference here.

Fantasy coins have yet to receive any major academic study. Yet studying these coins in an academic fashion is of great use in understanding modern conceptions. This is particularly true of the “historical” ranges of Greek and Roman coins. As a form of reception studies, one can see what particular images a modern audience considers as being “most Roman” or “most Greek”. The more fantastical ranges are also of interest, as it would be curious what real-world influences are attributed to these fictional races. Overall, the production of Fantasy coins shows that in the modern world where most transactions are carried out online or through credit, coins continue to attract interest.

|

This month's coin was written by David Swan. David is a postgraduate researcher at the University of Warwick. His thesis examines coinage and hoarding patterns across the Channel in Iron Age Europe. He specialises in Iron Age (otherwise known as Celtic) coinage.

Clare Rowan

Clare Rowan

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…