A “Vota Publica” token of the usurper Nepotian?

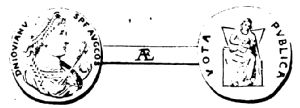

Among the numerous Roman tesserae and coin-like objects that have been emerging on the market in recent years is an unusual specimen made of bronze, which can be associated to the “Vota Publica” token series (AD 305/306 – c. late fourth century) (Fig. 1). As is comparatively known, this late Roman emission consists of two clusters displaying the portrait of a Roman emperor or an Egyptian deity (Serapis, Isis, Hermanubis) on the obverse – hence they have been respectively named as “imperial” and “anonymous” series – which share a set of ritual scenes referring to different aspects of Egyptian and Isiac cults on the reverse, mostly accompanied by the legend “Vota Publica’” (= “public vows”).

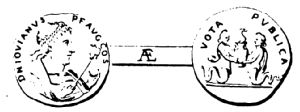

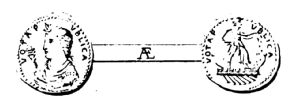

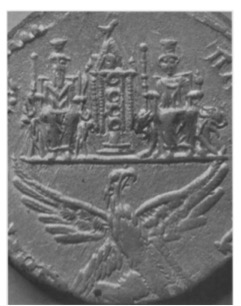

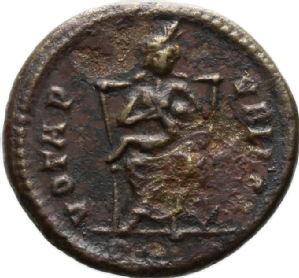

On the obverse of the focused token is a bare-headed, draped, male bust facing right, with a pointed nose, a short, grape–shaped beard, and a coiffure with straight hair except for a row of curls on his forehead, which is accompanied by the legend DEO SE-RAPIDI in the dative case (“to the god Serapis”). This portrait has none of the typical features of Serapis iconography, such as a mature look, a voluminous beard, and above all a grain measure called a modius or kalathos worn as a headdress (accompanied by a radiate crown in some variants), which regularly typify the Egyptian god on the tokens from the “anonymous” group (Figs. 2-3). It should thus represent a different male figure which is not otherwise identified by the legend. On the reverse is a draped (and veiled?) female figure standing front, head turned l., holding uncertain objects in each hand, accompanied by the peculiar legend VOTA P-VBLICA. These two obverse and reverse types are unrecorded and are therefore worthy of closer examination.

|

|

Figure 1: Æ “Vota Publica” token (15mm, 1.59g, 11h). Artemide Aste 19.1E, 20-21 October 2012, lot 381. Reference: L. Bricault & C. Mondello, Isis Moneta. The ‘Vota Publica’ tokens from late antique Carthage and Rome (forthcoming), cat. no. E169.1.

|

|

Figure 2: Æ “Vota Publica” token (19mm, 2.93g). Ashmolean Museum (inv. HCR71378, Douce coll.). Reference: L. Bricault & C. Mondello, Isis Moneta. The ‘Vota Publica’ tokens from late antique Carthage and Rome (forthcoming), cat. no. S83.1.

|

|

Figure 3: Fig. 3: Æ “Vota Publica” token (18mm, 2.52g). Gorny & Mosch 278, 21.04.2021, lot 3851. L. Bricault & C. Mondello, Isis Moneta. The ‘Vota Publica’ tokens from late antique Carthage and Rome (forthcoming), cat. no. S86.3.

The specimen, with a module of 15mm and a weight of 1.59g, was offered for sale in an online auction about ten years ago but remained unsold. In the relevant auction catalogue, the token was given as a very rare (genuine) piece (“RRR”). As for the imagery, the commentator identified the obverse portrait as the emperor Julian (AD 361-63) and described the female figure on the reverse as Isis, holding a sistrum in her right hand and situla in her left (sic). Nevertheless, this description does not appear to be supported by the evidence provided by the official coinage nor by the obverse and reverse depictions occurring on the surviving “Vota Publica” tokens.

Julian’s portrait as Augustus (AD 361-363) is commonly figured on coins in the guise of a draped and double–pearl diademed bust, with a mostly long and pointed beard, either wearing military clothing or consular garb; with such features it also recurs in some of the “Vota Publica” token issues, where the ruler is clearly identified by the legend D N FL CL IVLI-ANVS P F AVG or FL CL IVLIA-NVS P F AVG. Inspired by the Greek philosopher’s model, the short or long-bearded portrait of the last ruler of the Constantinian dynasty constituted a “revolutionary” innovation with respect to the iconographic tradition of the new clean–shaven portrait of the emperor in late antiquity which was established by Constantine I (AD 306-337). However, the Julian-type portrait of the Julian type failed to prevail over the Constantinian imperial portrait model which, inspired by Augustan and Trajanic imagery, was later followed by most emperors in the West and East across the fourth and fifth centuries.

Although the male portrait in Fig. 1 is also bearded as in the case of Julian, its general features do not match the latter’s coin portraiture. Closer parallels can instead be found in the coin images of another fourth-century bearded ruler, the usurper Nepotian.Son of Virius Nepotianus and of Eutropia (half-sister of Constantine I), seemingly born after the dynastic purge by the sons of Constantine I in the summer of AD 337, Nepotian was hailed emperor by a mob on 3 June 350 after the revolt of Magnentius, and ruled the city of Rome as usurper for twenty-eight days, before being killed by his rival Magnentius’ magister officiorum Marcellinus. As a usurper, he struck coins in his own name (as well as in the name of Constantius II), the production of which was limited to the Roman mint and only consisted of two denominations, that is solidi and large billon AEs. On the two “Urbs Roma” and “Gloria Romanorum” series, the portrait of Nepotian occurs either bare-headed or rosette-diademed, with an oblong face shape, a peculiar hooked nose, a short beard, and curly or straight hair with a mostly wavy fringe.

As can be seen in Figs. 4 and 5, the vultus of Nepotian and general features of his coin portrait seemingly have some affinities with the bearded bust on the obverse of the focused “Vota Publica” token.* If this assumption is correct, such a relation may suggest that the former inspired or served as a model for the latter, although it must be said that there are some slight differences which are probably due to a different engraving style. On the other hand, in this author’s opinion, no remarkable parallels can be found with the few bearded portraits of the emperors or usurpers of the West and East on coins issued since the post-Tetrarchic period (e.g., Martinian, Vetranius, Procopius, Eugenius, Maximus of Hispania, Joannes), nor with those on Roman medallions and “contorniates” from the fourth and fifth centuries AD.

|

Figure 4: Large Æ2 (c. 24mm, 5.36g), usurper Nepotian (AD 350), “Urbs Roma” series (= RIC VIII, Rome 203).

|

|

Figure 5: Large Æ2 (5.05g), usurper Nepotian (AD 350), “Gloria Romanorum” series (= RIC VIII, Rome 200). Numismatik Lanz München, Auction 100, 20.11.2000, lot 581.

As for the reverse, the overall scheme of the type showing a female figure standing front in Fig. 1 is reminiscent of Isis’ common depiction, standing with her body supported on one leg, while brandishing a sistrum (a percussion musical instrument associated with her cult) or a palm branch in her right hand and a situla (a bucket for holy water), sometimes replaced by a patera (a libation bowl), in her left (e.g. Fig. 3). However, the draped figure on the token cannot be identified with the Isis as she lacks a basileion and other attributes which typify the goddess. The objects held by the figure remain difficult to decipher, which could maybe be interpreted as a branch of a not recognizable tree or plant in her right hand and a strip of drapery in her left. Therefore, this precludes to enlighten the precise nature of the reverse motif. Looking at the types belonging to the reverse figurative repertoire of the “Vota Publica” series, the female figure in question appears to be conceptually closer to the depictions of auxiliaries and participants in (Isiac?) religious ceremonies (e.g. torch and candelabra holders, canephores, female attendants, and devotees) (e.g. Fig. 6) than to those of the goddess Isis.

|

|

Figure 6: Fig. 6: Æ “Vota Publica” token (14mm, 1.41g, 12h). Naville Numismatics 12, 18.01.2015, lot 249. Reference: L. Bricault & C. Mondello, Isis Moneta. The ‘Vota Publica’ tokens from late antique Carthage and Rome (forthcoming), cat. no. I154.4.

Interestingly, this token mixes some features from the “imperial” series (= the depiction of a bust of an alleged Roman emperor or usurper on the obverse) and the “anonymous” one (= the obverse legend “Deo Serapidi”), which were both part of the “Vota Publica” token emission. As recently shown (Bricault & Mondello, forthcoming), the “imperial” series consists of a small first issue from the mint of Carthage dating back to the Second Tetrarchy (AD 305-306) and the Third Tetrarchy (AD 306-307), and a subsequent, large production from the mint of Rome struck from the reign of Constantine I (AD 313-330/331) through at least the first two generations of the Valentinian dynasty (AD 365-378). In contrast, the “anonymous” series is devoid of any chronological reference from which a reliable date can be inferred. Due to die-linkage with some of the Valentinianic groups from the “imperial” series, the “anonymous” series has commonly been regarded as a product of the Roman mint and dated to the years between AD 379-380 and 395, based on some stylistic and historical assumptions (Alföldi 1937, p. 17). However, it remains debated when the production of this undated series began and ended.

If the male portrait on the obverse of the outlined token was indeed intended to represent the usurper Nepotian or was at least borrowed from his official coinage, it may shed light on some aspects of the “anonymous” series manufacture. Among other options, one might consider the token as a trial piece or as part of a transitional group between the “imperial” and “anonymous” series by virtue of its mixed characteristics; or, it could even lead one to consider pre-dating the starting point of the “anonymous” series to AD 350.

However, in this author’s opinion, some remarks on the iconography of the specimen and its historical background may raise serious questions on its genuineness.

Not only are the types occurring on this token unattested, but even certain of their details look anomalous. Regarding the obverse, the anonymous male bust does not constitute a full copy of Nepotian’s coin portrait, as seen above. Rather, the former seems to arise from a re-working of the latter by the engraver, despite the close affinities between them. Noteworthily, the curls on the forehead of the male portrait on the token have a quite unnatural round shape, the appearance of which seems reminiscent of the rosettes forming the imperial diadem often occurring on fourth century Roman coins, including Nepotian’s Roman issues. One might imagine that the die-cutter misrepresented a rosette diadem as a sort of curly fringe when designing the obverse portrait on the token, maybe in an attempt to imitate one of Nepotian’s portraits occurring on the relevant Roman coin dies. In contrast, it seems unlikely that the curly fringe of the male bust’s hair is in fact to be understood as a rosette diadem, due to its position as jutting out on the forehead instead of being placed on the top of the head, as well as given the absence of any diadem’s ties which normally flowed down behind the ruler’s neck on coin imperial portraiture.

Moreover, the obverse of the token deviates from the epigraphic pattern attested on the extant pieces. In fact, the legend DEO SERAPIDI only accompanies the portrait of Serapis, Hermanubis, or even the jugate busts of Serapis and Isis on the obverses of the “anonymous” series, and is never combined with the portrait of a different figure.

Likewise, inconsistencies can also be found on the token’s reverse design. For instance, the right hand of the female figure and the object she bears were drawn as single whole here. As with the obverse type, this “oddity” could also result from an error or misrepresentation by the engraver, who maybe depended on one or other of the variant of Isis holding a palm branch in her right hand, as found on the reverses of the “Vota Publica” tokens. Moreover, it is worth noting that the style of both types has no parallels with any of the surviving “Vota Publica” tokens, which seem to have come out of a different workshop.

Further to these considerations on iconography and style of the token, some aspects related to its expected distribution context also need to be considered. Nepotian’s accession and death dates do not match the date and context in which the “Vota Publica” tokens were supposedly distributed, namely the imperial “public vows” pronounced annually on the 3rd January against the backdrop of the New Year’s festivals. As reported by some late antique literary sources (Descriptio consulum, Eutropius, Jerome, Socrates), Nepotian seized power on 3rd June AD 350 and held it for twenty-eight days until his death, 30 June or 1 July. Therefore, no token could have been issued in the name or with the portrait of this usurper for the public vows on 3rd January in that year or even the following year(s). After all, if one were to consider the possibility that Nepotian’s coin portrait was only used as a model for “Vota Publica” token issue struck at some point since AD 351, cui bono (“to whom is it a benefit”)?

Ultimately, the above analysis suggests that the token may be the result of a counterfeit, most likely made in modern times. Such a forgery may have resulted from the combination of genuine coin image prototypes, which were respectively taken from the Roman coinage of Nepotian (= obverse type) and the “Vota Publica” token series (= reverse type). These images were reworked by the engraver and paired with legends from the “Vota Publica” token series, in order to create an otherwise unknown specimen in an attempt to increase its market value.

We hope that a metallurgical examination of this specimen, currently held in private hands, could be conducted in the near future in order to solve this dilemma.

* Thanks are due to Dr Vincent Drost (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des monnaies, médailles et antiques) for suggesting a possible relation between the obverse type of the token discussed here and the coin portraits of the usurper Nepotian.

This blog was written by Cristian Mondello as part of The ‘Vota Publica’ Tokens from Late Antique Rome: Isiac and Egyptian Cults within a Christianizing Roman Empire project, which has received funding from the NRRP, Mission 4, ‘Education and Research’ – Component 2, ‘From Research to Business’ – Investment line 1.2, ‘Funding projects presented by young researchers’ (European Union – NextGenerationEU, proposal no. CFFE1C55, CUP J43C22001030001). The project is hosted at the University of Messina, Italy.

Select Bibliography

- Alföldi A., Isis-szertartások Rómában a negyedik század keresztény császárai alatt = A Festival of Isis in Rome under the Christian Emperors of the IVth Century, Budapest 1937.

- Bricault, L., & Mondello, C., Isis Moneta. The ‘Vota Publica’ Tokens from late antique Carthage and Rome. Volume 1: Catalogue, London (forthcoming).

- Burgess R.W., ‘The Date of Nepotian’s Usurpation’, Historia 72.3, 2023, pp. 370-384.

- RIC VIII = Kent, J.P.C., The Roman Imperial Coinage. The family of Constantine I. A.D. 337–364, Vol. VIII, London 1981.

Favourite blogs for

Favourite blogs for

Clare Rowan

Clare Rowan

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading