Dionysiac Dolphins: coinage and social identity

|

| Dolphin coin of Olbia (SNG BM Black Sea 360) |

This dolphin-shaped money was found at Olbia, a trading colony of Miletus on the coast of the Black Sea, and dates from the late sixth century. The coins are made of bronze, and are approximately 35mm in length. Archaeologists believe the use of these pieces to be monetary because they carry leaders’ names and are found in hoards and in tombs. Although the dolphins were eventually replaced by more conventional round currency which incorporated the image of a dolphin into its design, the dolphin shape builds on a Greek tradition of using dolphin iconography as a way of representing the internal struggle to define identity in the face of increased interaction with foreign culture.

Dolphin imagery is used in both literary and artistic depictions of Greek culture in the time of colonisation, embodying the separation between Greece and the outside world. The distinction between self and other played an increasingly important role in the lives of Greeks as colonisation and trade grew. The need for outside materials such as grain (which did not grow well in Greece) or metals and the need for land (a requirement for citizenship) increased awareness of the cultural and linguistic differences between Greeks and non-Greeks. This heightened the urgency with which the Greeks began to define themselves.

|

|

Dionysus sailing surrounded

by dolphins.

|

One literary depiction of the dolphin is in Herodotus (1.23): a dolphin rescues Arion from death at the hands of rogue sailors during a war against Miletus. The Histories are full of contrasts: home and away; barbarism and civilisation. This story uses these contrasts to explore the dichotomous and fraught relationship Greece was developing with the outside world. The dolphin in this instance represents a protector of civilisation by rescuing the creator of dithyramb (a sympotic song, sung in honour of Dionysus): a core part of the established social patterns of Greek culture. Although the sailors were also Greek they demonstrate a loss of civility having left behind the civilisation of Greece: once Arion returns to Greece, he is again honoured.

Archilochus discussed the opposition between land and sea, creating a sense of opposition between the safety of Greece and the uncertainty of sea-faring: “the forest beasts remove to dolphins’ salty fields, finding roaring waves a sweeter home than land” (122W). Although this colonisation is not the primary context of the fragment, the use of contrast and sea imagery clearly references the use of the sea to explore new territory. Contextually, this poetry would be performed at symposia and perhaps not in the traditional sense: Carey (2009) notes the possibility that the symposium was removed to the ship – the performed lines reflect the literal situation of the sailors, allowing them to define themselves as a group separate to Greece, using the habitat of the dolphins to create a home-away-from-home for themselves.

|

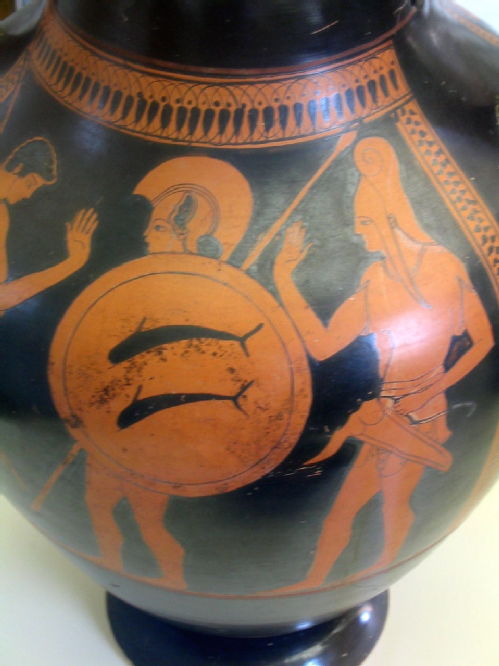

| Hoplite warrior

with shield

|

In art, the use of the dolphins is also connected to the symposium: Dionysus rides through the sea on a boat surrounded by dolphins, with vines growing above his head. The idea of nautical transportation not only connects to colonisation, but also to the “long distances” drinkers traversed through wine (Davidson, 1998). The symposium offered a space for self-discovery, performance of the self, and exploration of the new world the Greeks were facing. The symposium is linked intrinsically to the story of Arion, creator of the Dithyramb through the musicality and theatricality of the symposium, the dolphins acting as a “visual projection of dithyrambic chorality” (Kowalzig, 2013). Dolphin iconography here then demonstrates both the physical and mental transportation of Greek cultural awareness and definition.

In other vases, dolphins appear in the context of warfare, playing antipathetic roles of protection and attack. In the context of the hoplite, the dolphins are seen being ridden into battle, and also on the shield: they are figured as a Greek asset, turning the sea into a battlefield both physically in the form of naumachy but also figuratively in terms of the mental battle between need for expansion and will for Hellenist isolation. The sea is being claimed as Greek through the appropriation of the dolphin.

|

|

Hoplite warriors riding

dolphins into battle.

|

The use of dolphin iconography in the Olbian coin can arguably be considered to be about identity. Although the evidence discussed so far has explored how the Greeks used the dolphin to figure their identity, this is also an important question for a colony with significant outside interaction from trade. Olbia is not the only colony to use the dolphin image in this way: Taras, the only colony founded by Sparta, used the image of a dolphin-rider on their coins, perhaps to emphasise the militaristic connection to Spartan society. The dolphin allows a connection to be made to Greek culture through sympotic and competitive ideals drawn from the literary and artistic tradition. There are also links to the temple of Apollo Delphinos, again demonstrating the prioritisation of the Greek connection for the colony. However, it also allowed Olbia to create its own separate identity. Dolphins inhabit the physical space between Greece and her colonies; by highlighting this gap the colony emphasises its otherness. Olbia also created a law insisting that all trade took place in Olbian currency, although this came later at c.350BC, suggesting that at all points in the colony’s history independent identity was important for a colony with so much foreign interaction. The dolphin coin, with precedence in Greek culture, allowed Olbia to create her own identity separate to Greece and separate to Miletus.

This month’s coin was written by Lucinda Hughes. Lucinda graduated from Warwick in 2014 with a BA in Classical Civilisation, which gave her a continued interest in Greek and Latin literature. She is now studying for an MSc in Business (Finance and Accounting) at Warwick Business School, and begins work at Nomura International in September.

Select Bibliography:

Carey, C (2009) "Genre, Occasion and Performance", in The Cambridge Companion to Greek Lyric, eds. Budelmann (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge).

Davidson, J. (1998) Courtesans and Fishcakes (Fontana Press, London).

Kowalzig (2013) “Dancing Dolphins on the Wine Dark Sea” in Dithyramb in Context, eds. Kowalzig and Wilson (Oxford University Press, Oxford).

Images:

Dolphin coin: © Trustees of the British Museum.

Plate showing Dionysius: "Exekias Dionysos Staatliche Antikensammlungen 2044" by Exekias - MatthiasKabel, Own work, 28 January 2006. Image renamed from Image:Dionysos Augenschale des Exekias.jpg. Licensed under CC BY 2.5 via Commons.

Amphora depicting hoplite warrior with shield: "Athenian red figure Amphora" by Dan Diffendale, own work, 2 September 2005. Licenced under CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Hoplite warriors riding dolphins into battle: Reproduced courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, "Terracotta psykter (vase for cooling wine) attributed to Oltos, accession no. 1989.281.69.

Clare Rowan

Clare Rowan

Loading…

Loading…

Add a comment

You are not allowed to comment on this entry as it has restricted commenting permissions.