All entries for Wednesday 01 July 2015

July 01, 2015

Augustus and the gods

RIC Augustus 367, BMC Augustus 98 = LACTOR, Age of Augustus L1. Silver Denarius, 16 BC

Obverse: Bust of Venus right. C ANTISTVS VETVS IIIVIR = ‘Gaius Antistius Vetus, tresvir (monetalis)’

Reverse: symbols of priestly offices – the ladle (simpulum) top left, augur’s wand (lituus) top right, tripod bottom left and sacrificial bowl (patera) bottom right. COS IMP CAESAR AVGV XI = ‘Imperator Caesar Augustus, consul for the 11th time’.

|

| Gemma Augustea |

Res Gestae divi Augusti 7.3 ‘I have been chief priest, augur, one of the Fifteen for conducting sacred rites, one of the Seven in charge of feasts, Arval brother, member of the fraternity of Titus, and fetial priest.’ Many passages of the Res Gestae find echoes in contemporary coinage. For Augustus, this list of his priesthoods was just as important as the magistracies which he had listed in the previous sentence. It was a common sentiment in Roman texts that the Romans’ divisive civil wars was a consequence of their neglect of the gods, who in turn then punished the Romans by provoking them to fight each other rather than the barbarian enemy who ought in the normal course of events to be the focus of any warfare. So the solemn opening of one of Horace’s so-called ‘Roman Odes’, 3.6, states ‘Ancestral crimes, though innocent, you’ll pay the gods for, Roman, till you restore their temples, their crumbling shrines, and images with black smoke besmirched’ (LACTOR G28). It is a commonplace to point out that, for Romans, their magistrates were their priests, and that religion and politics were regarded as inseparable. A Roman would not have understood the modern criticism made by some in contemporary Britain whenever a bishop or archbishop takes a stand on a point of politics.

|

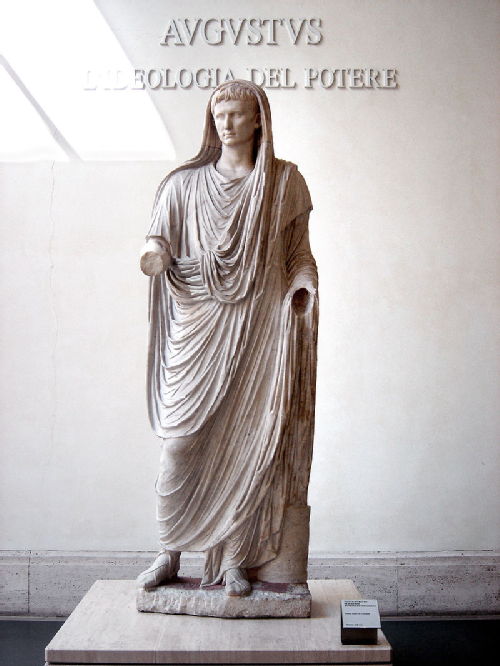

| via Labicana Augustus |

But in Augustus’ case, this coin is an excellent example of his typical blend of tradition and radical innovation. The presence of Venus on the obverse reminds us of the claims made by the Julian family to be descended from the goddess herself, via Aeneas, whilst the images on the reverse allude to the four major priesthoods in Rome. The ladle alludes to the pontifices, who had overall control of state cults; the lituus is both the wand used by the augurs in taking the auspices by observing the flight and song of birds and also a visual pun upon Augustus’ own name (compare too its appearance in Augustus’ hand on the gemma Augustea); the tripod alludes to the quindecimviri sacris faciundis, the college who were in charge of foreign cults in Rome, including consultation of the Sibylline oracle and the celebration of the Centennial Games; and finally, the patera recalls the college of the septemviri epulones in charge of sacred feasting at Rome. Traditionally, an individual held only one priesthood for life. Augustus had first been made a pontifex as early as 47 BC, in place of Domitius Ahenobarbus who had been killed at the battle of Pharsalos: he owed this promotion to the influence of his great-uncle Julius Caesar, who himself had exceptionally been a member of three priestly colleges. But it was Augustus who ended up as the first Roman ever to be a member of all four major colleges (and several minor ones too), accumulating them gradually over time, being elected augur in c.42 BC, quindecimvir in c.37 BC, and septemvir by 16 BC. One of the statues of Augustus most famous today – the via Labicana statue from Rome – depicts him in his role as priest, with veiled head. He makes the multi-titled Pooh-Bah of Gilbert and Sullivan’s Mikado – ‘First Lord of the Treasury, Lord Chief Justice, Commander-in-Chief, Lord High Admiral, Master of the Buckhounds, Groom of the Back Stairs, Archbishop of Titipu, and Lord Mayor, both acting and elect, all rolled into one’ – look almost unambitious! Both of these characters – though one fictional and the other real – may be compared for the way in which they both managed to bundle together the functions of the state into their own person. As Tacitus claimed, in the opening of the Annales, ‘he gradually increased his power, arrogating to himself the functions of the senate, the magistrates, and the law’.

By the end of Augustus’ lifetime, the link between Rome’s prosperity, the goodwill of the gods, and Augustus himself as the crucial intermediary with the gods in securing their support for Rome, was a message that was clear from a variety of visual and textual media.

This month's coin was chosen by Alison Cooley. Alison usually devotes her energies to Latin inscriptions, but is always delighted to have an excuse to look at coins too. Her commentary on the Res Gestae (CUP 2009) discusses other ways in which coins overlap with the messages promoted by that fascinating inscription. She is currently working on a project re-editing Latin inscriptions in the Ashmolean Museum: see our blog, Reading, Writing Romans.

Coin image © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Gemma Augustea CC-BY-SA 3.0 ("Gemma Augustea" by Dioscurides (?) - Self-photographed, October 2013 (James Steakley). Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons)

via Labicana Augustus from Wikimedia Commons. ("CaesarAugustusPontiusMaximus" by RyanFreisling at English Wikipedia - Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Clare Rowan

Clare Rowan

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading

Loading…

Loading…