All 43 entries tagged Ideation

Well ordered conceptualisations forming prototype arguments and solutions to be tested against real world situations.

View all 55 entries tagged Ideation on Warwick Blogs | View entries tagged Ideation at Technorati | There are no images tagged Ideation on this blog

July 20, 2011

Learning ecologies – visualisations

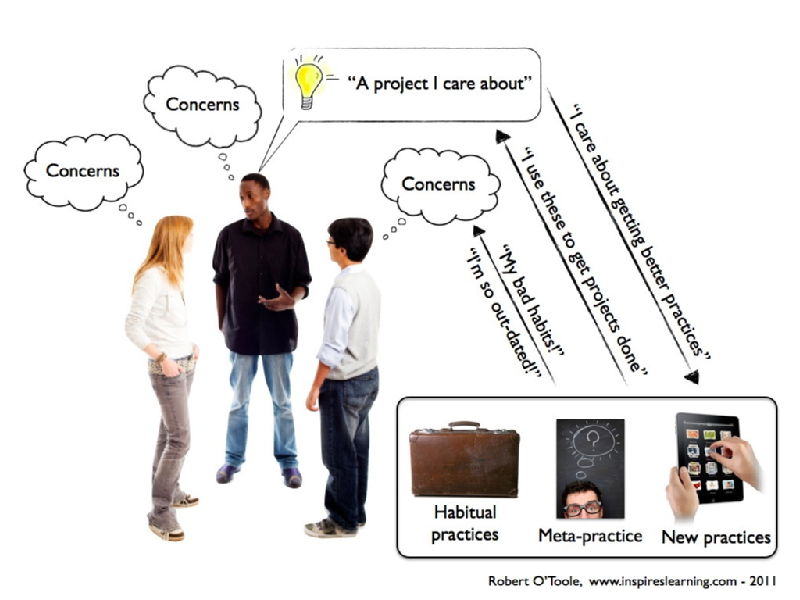

Concerns can be of many kinds - both active and reactive, vague or specific. Sometimes we are concerned about our own practices, wishing to change them, or defending them against change. People reflect upon their concerns in some quite different ways. That effects how they get transformed into projects, and how they reflect practices.

Projects are changes or productions that we care about and work on over time to achieve a more or less well-defined outcome. They often create or revolve around some definite artifact of a well known genre (e.g. a thesis). Sometimes they might concern the creation of a more substantial and less easily contained change (e.g. "a new me"). Projects may be explicitly about changing practices (our own or those of others). Projects can be co-productions. An organised even is a project - for example, a seminar is a co-production.

Projects can be formed and structured by the individual with relative autonomy, or follow a pattern defined institutionally, or they might be a compromise (negotiated or otherwise).

Practices may be habitual or exceptional, procedural or innovative. We have meta-practices that allow us to reflect upon, evaluate, choose and change our practices. Knowing is itself a practice. Technologies are artifacts that are designed to work within practices (their affordances and constraints), to achieve projects that satisfy concerns. "Technology is society made durable" (Latour, 2000)

Images by urbancow & mattjeacock - istockphoto.com

May 12, 2011

Innovating in HE teaching & learning support using participatory design thinking

A brain-dump, which might turn into a full article, and certainly a chapter...

Academic course modules in HE (the standard unit of assessed activity) are conventionally understood as being an assemblage of teaching activities (e.g. lectures), resources (a reading list), and student responses (learning, presentations, essays, exam responses). I have always found that model to be too superficial as a means for designing learning and teaching support and development. It fails to grasp the contentiousness of academic projects. For example, what it means to study and to know seventeenth century literature is contended, and that contentiousness is an important (perhaps the most important) matter to be grappled with by the students. Should students studying 17th C lit go no further than the established canon given in the Norton Anthology? Should they explore authors, texts and contextual issues that might normally be considered to be peripheral? If those lesser-known authors demand a more original and creative response, perhaps using film making and other new technologies, is that allowable within the module? How can the established canon then be reinvigorated using new techniques?

The simplistic model fails to grasp the dynamic, negotiated, 4 dimensional nature of teaching and learning. It overlooks the many points at which the module is actively designed and redesigned. When introducing a new practice, a new technology, it is within this contention rich and ever changing context - practices are contended, and differences may have significant implications. An effective methodology for improving learning and teaching through technology must employ a design strategy that works with this dynamism.

Confused? That's a common response. Choosing or designing technologies to introduce to a module, supporting their integration and use, and measuring their impact, is dependent upon lots of variable local conditions. We most commonly introduce technologies at a more global level, and fail to address their integration into the complex context of the module.

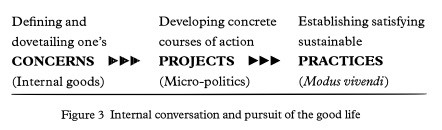

So, here then is a model that is more sensitive to local conditions, contentions, complexities and change. It takes as its starting point a simple model of social agency provided by the sociologist Margaret Archer in Making Our Way Through the World (2007):

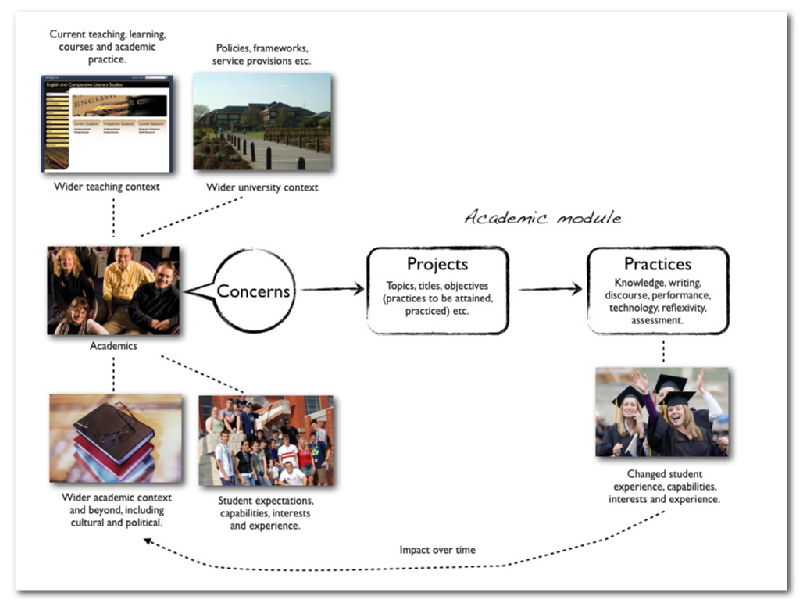

To some extent it is idealised. Most modules as taught now are in fact adaptions of existing modules. Not designed from scratch, but redesigned. On the left hand side (in the idealised model), there is a group of academics. They collectively bring together their concerns (as the academic experts) and those of other institutional bodies and people (the course structure, the needs of the discipline, the inadequacy of current practice, the ethos of the university, the students etc), filter that assemblage of concerns into the kind of academic project that we call a module (designed within a given set of affordances and constraints). There are various creative, political and administrative practices that result in a module forming as a project from these concerns. Typically, the module as an academic project is then defined in module handbooks, the prospectus, and verbally to the students at events such as options fares. The module is bounded territorially, and through a set of affordances and a set of constraints. This definition will usually outline:

- The foundational concerns (often in a persuasive or rhetorical manner);

- The sub-projects (lecture topics, essay titles etc)

- A set of appropriate practices (including knowledge, writing and its practices) are explicitly or implicitly defined for the module. They vary between practices with which the student must enter the module, practices that they will develop during the module, as well as practices the development of which are themselves a concern and a goal of the module as a project.

The module is typically expressed as a journey: sign up to the concerns, the project and its practices, and you will get to some better place (better practices, better understanding, or perhaps a better grade). In the humanities, the student is expected to create their own variation of this journey - for example, in creating their own research topic and essay title - as well as, sometimes, critically introducing their own variations on the core practices (for example, introducing a different critical perspective, or using different writing styles).

There are many dimensions of change within this. The most significant being:

- The student will develop new/better/more useful practices.

- The practices upon which the module is based will change (over time, as a result of student and teacher innovation).

- A wider impact may trickle out, eventually changing the department, the discipline, the university, society and culture.

What does this mean for learning technologists and others? The service improvement process needs to be driven by some form of common ground drawn from these innovation processes as they happen in the wide diversity of modules. But also, any intervention at a global level (for example introducing a technology across a whole university) should be accompanied by assistance to co-adapt the innovation with the constant multi-dimensional innovation happening at the heart of module based teaching and learning. Sounds like a cue for participatory design thinking.

As a diagram:

April 26, 2011

Blogging for academic and personal development, a short video

I've just recorded a short talk about blogging for the History Subject Centre. In it I talk about how blogging as a form of writing (not a genre) pushes the blogger to behave in a specific kind of authorly manner. The blog presents affordances, constraints and enabling constraints, and when used in a certain way, can be an effective means for reflexively developing personal discoursive skills - an individual's 'voice' and (academic) 'technique' (I'm currently reading Writing: Self and Reflexivity by Celia Hunt and Fiona Sampson, which deals well with these ideas).

Transcript:

The term 'blog' is a shortened form of the phrase 'web log' - indicating that it is a log or diary of events that is written on the web. It's as simple as that. That doesn't imply anything about it's content or purpose. We shouldn't assume that all blogs are written for the purpose of self-publicity, or that all blogs are about trivial events in the life of the blogger. Indeed, not all web logs will have an audience, a single author or a common theme. Often when encouraging students to take on a blog, the first obstacle is to get them to understand that blogging is a form and not a genre of writing.

That does not however mean that the blog isn't a powerful and productive form. It is. It's essential structure encourages the blogger to think, read and write in a particularly interesting way. Consider the basic pattern: the blog contains a series of date-stamped texts, each of which is oriented towards some external thing or event that has occurred on or near to that date. Even if the entry were about an event in distant history, the time-boundedness of its publication in the blog ties it to a reflection of that distant event by the author at the time of publication. The empty form of the 'new entry' interface asks for a title, nominating some purpose for the writing. Typically the title must conform to a tightly constrained length, forcing the author to think about the essence of the entry. The body of the entry provides greater scope for expression, digression and consequently blogger's-block. The ability to add images, formatting, hyperlinks and multimedia offers routes by which the challenge of the blank entry may be overcome. But most importantly, the blank entry form demands some thing more of the blogger. They need a discipline of some sorts with which to fill it. It may be enough to attend to an interesting and significant event or object. But more usually, for successful blogging, the blogger needs to deploy some means for interogating the object or event with a writing strategy - for example, a set of questions.

So, a blog demands to be much more. It is a space that the author must fill through a mediated representation of an interesting object or event. The author is out-there, on the look-out for material. Upon finding material, they interrogate, expand it, filter un-necessary detail, get the right angle on it, and use their powers of expression to convey that story.

And yet there's even more to it. The entry need not necessarily lay dormant. The datedness of the entry may always pose the question: that was then but what of now? How might the event, the object, the author and the reader have changed over time? Most blog systems offer means for searching or browsing back in time. The blog is more than just a place to write an entry, it is a time machine. And there lies the real power of blogging: reflexivity. We can use a blog to review our past selves. To think about change, agency (or lack of), and to think about what might be possible in the future. For example, on a simple level, a student can refine the questions that they ask when investigating an event. They might over time find themselves more able to hear and amplify their own personal voice in theie writing. They might work with a tutor or their peers to refine the direction of their development. A blog may then be a medium in which we mediate between the world of events and objects, the individual, and academia.

So, to conclude, some recommendations on blogging for academic and personal development:

1. As with almost anything that is worthwhile, you need to acquire and apply an apporopriate discipline to your blogging. To become a good blogger, and hence to benefit from its potential for developing you and your writing, be an active and regular blogger, seeking out material and working it into entries.

2. Who are you writing for? Define your audience, large or small. It might even be an audience of one - you yourself (or your many future selves). Perhaps think of your blog as having distinct zones, ranging from a personal zone, through small group zones, to an entirely public zone. Perhaps you should first publish to the personal zone, and progressively widen-out your audience.

3. Actively seek out experiences to fuel your writing. Learn or invent tactics for finding good subject matter, or for making things happen.

4. Invent and refine systems for interrogating your subject matter - for example, a series of questions that you always start by asking.

5. Don't be overwhelmed by your audience or your subject matter. Retain the right to your own perspective. Make sure there's always something of yourself in there.

6. Quality does matter, even if you are only writing for yourself. But don't let it stifle your creativity and spontaneity. Write some content that is clearly identified as fast and immediate. Wrap it in text that is more considered and formal. Or use photos, audio and video to capture the moment. Then describe the moment with more well-developed, edited text.

7. Revisit your entries after some time. It's easier to be objective about your past self than it is about your present self. Set yourself objectives for quality and content.

Robert O'Toole

Robert O'Toole

Please wait - comments are loading

Please wait - comments are loading